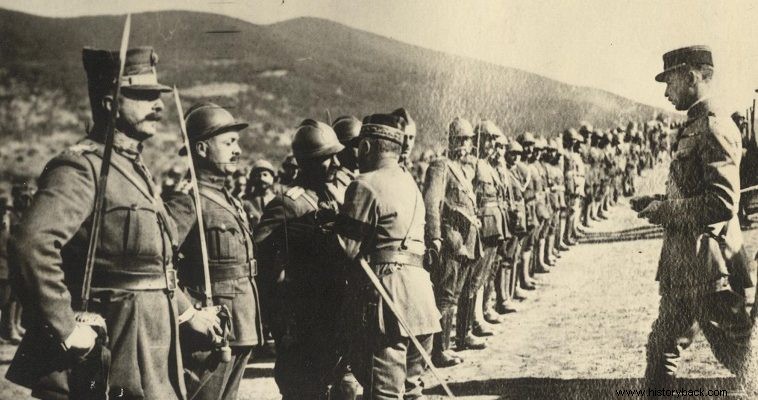

The Battle of Doirani took place during World War I, on the two days of September 18 and 19, 1918. It was an offensive operation by Entente units against Bulgarian forces on the Macedonian Front, in the wider area of the homonymous lake. The operation was carried out by the British Hellenic Army, a part of the Allied Eastern Army, consisting of nine divisions:four British, five Greek and one Greek cavalry regiment.

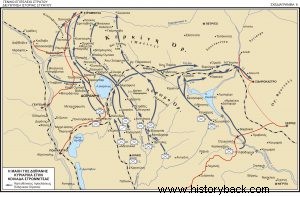

The operation was part of the plan for a general attack across the entire Macedonian Front by French General Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Army East. The plan was to split the front and pursue the enemy in great depth. The undertaking of a general attack was decided by the Allied governments after a detailed assessment of the political and military situation. The conditions that led to the upgrading of the strategic value of the Macedonian Front were a consequence of the developments on the Western and Italian Fronts.

Specifically, on the Western Front, the Germans, in the spring of 1918, after their victory over the Russians, implemented Operation MICHAEL and launched an attack on the entire Theater of Operations. The business was initially successful. In May 1918, after the Battle of the Marne, German forces were now close to Paris. Tactically the operation was a major victory for the Germans. Strategically, however, the implementation of the operation marked the beginning of the end of the Central Powers2, as it forced Germany, which was by far the strongest of the alliance, into an effort beyond its then existing capabilities.

In particular, in the spring of 1918 Germany had no lines of administration extending deep into French territory while at the same time suffering from significant shortages of critical supplies. Further stretching the German divisions to their maximum operational capacity and simultaneously depleting their reserves made them vulnerable to an Allied counterattack. At the same time, the needs of the operation in the number of men forced the withdrawal of almost all German forces from the Italian and Macedonian Fronts. In conclusion, the tactical success of the Germans, apart from being temporary, as their forces did not have the ability to exploit their victory, created a series of strategic problems on all fronts of the war.

On the other hand, the Allies, reinforced by American forces, took advantage of the German error and counterattacked throughout the Western Front, crushing the German divisions on the Marne and Amiens. At the same time on the Italian Front, the Austrian forces operating to the south were pinned down by the allied Italian forces. Having regained supremacy on the Western and Italian Fronts and realizing the opportunity to exploit the military weakness of the Central Powers on the Macedonian Front, the allied governments authorized d'Esprey to proceed with a general offensive. The idea was to put the Central Powers between a "hammer and an anvil" and d'Esprey would be the one to do the hammering.

The speed of the attack was critical. At this particular moment the Allies had a significant numerical and qualitative superiority. Specifically, in the summer of 1918, the Army of the East had a total of approximately 655,800 soldiers and 1,540 guns, which from the spring of 1918 included all ten Greek divisions. Against the Entente forces the Central Powers fielded 420,000 soldiers and 1,345 guns. But the withdrawal of the Germans had changed the composition of the forces:356,000 soldiers were Bulgarians who were considered of low combat value.

Apart from the military parameters, d'Espret's plan also took into account the national aspirations of the states whose troops participated in the war. Consequently he assigned the main attack to the Franco-Serbian forces in the center of the front as the Serbian Army was expected to fight vigorously to recapture national territory. The Greek Army, whose national aspirations were directed towards Eastern Macedonia, was placed in the Strymons sector, while the reduced British forces were assigned supporting and clearing missions, mainly that of using artillery.

The Battle of Doirani September 18 – 19, 1918

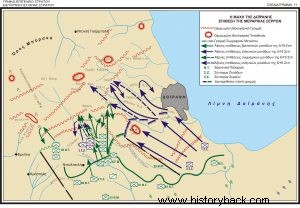

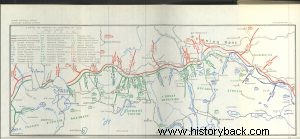

Within the above framework, the battle of Doirani took place on the two days of September 18 and 19, 1918. The battle was fought between units of the British Hellenic Army and the 1st Bulgarian Army in the area between the Axios River and the lake of the same name. The area was heavily fortified as the enemy had organized three successive lines of defense which included between one and three lines of barbed wire.

The general attack on the front began on 14 September and quickly succeeded in breaking up the defensive positions in the sector of the Franco-Serbian Army. Specifically, on the evening of September 16, two days before the attack in the area of Doirani, the rift that had been created in the enemy formation had a length of 25 kilometers and an average depth of 7 kilometers. During this initial phase the British Greek Army was limited to pinning down the enemy in front of its front as well as preparing to launch an attack according to the plan.

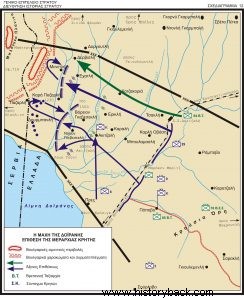

The British Hellenic Army consisted of two army corps, the XII and the XVI, which included a total of five Greek divisions and one Greek cavalry regiment. According to the plan of attack the XII British Army Corps would attack west of Doirani led by the Serres Division and the 22nd British Division, while the XVI would attack east of the lake with the Crete Division in the first line. The purpose of the attacks was in principle to pin down the enemy forces so that they could not reinforce the front at the point where the breach had been achieved by the Franco-Serbian forces. Afterwards, an advance towards the valley of the Axios river was planned in order to cut off the enemy's retreat.

The XII British Army Corps launched its attack at 0500 on 18 September 1918. The artillery preparation that preceded it took two days. British artillery destroyed the barbed wire of the first and second enemy lines while inflicting heavy damage on the third enemy line of defense. The attack was undertaken by the Serres Division and the 22nd British Division, which on the first day of the battle fought hard and suffered terrible losses without, however, making any territorial gains or succeeding in breaking the enemy defense. Indicatively, it is noted that the Greek 3rd Regiment of Serres, which had been given as reinforcement to the 22nd British Division, had 15 officers and 131 hoplites dead as well as 44 officers and 620 hoplites wounded.

During the second day of the battle the Serres Division managed to penetrate the main defensive works of the enemy location but the remaining British forces of the 22nd Division were decimated and forced to fall back. As a consequence of this, the Serres Division received heavy fire from all the enemy forces and was forced to retreat. The attack in the western sector had failed while the total losses of the British amounted to 165 officers and 3,155 hoplites killed and wounded and of the Serres Division to 173 officers and 2,514 hoplites. After the battle the Serres Division was moved to the rear for reorganization.

At the same time, the British XVI Army Corps launched its attack from the other direction at 0300 on 18 September. The attack was undertaken by the Crete Division. The Division began its advance without preparation by the artillery which until first light had not been engaged in the fight. Despite the successive efforts of the forward divisions during the day it was not possible to break through the enemy defenses while the Division suffered significant losses. The next day no offensive operations were carried out and on the night of September 19-20 it was replaced and arrived at a village in Kilkis for reorganisation. The losses of the Division amounted to 11 officers and 131 hoplites dead as well as 33 officers and 540 hoplites wounded.

The offensive operation in the area of Doirani had failed. The causes of failure are many. It should be noted that Greek army personnel had never before worked with allied forces and were not familiar with the methods by which British troops operated. Also, the area, apart from being strongly organized, was also unknown to the Greek troops, as they did not have the appropriate time to perform the necessary reconnaissance before the attack. In any case the battle was a heavy defeat with a high number of casualties for the Allies. The Greek commander-in-chief Panagiotis Daglis protested to the Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos stressing that the Greek troops, despite leading the offensive actions, were abandoned by the British and as a result suffered heavy losses.

But despite the high price and the failure to break the enemy's defenses, the major objective of anchoring the enemy forces in the wider area was achieved. Stuck in their positions and defending themselves, the Bulgarians did not manage to send reserves in time to restore the front at the point of the breach. As a result d'Espret hastened to take advantage of the gap by penetrating deep into the Balkans with the aim of crushing the enemy forces.

On September 28, 1918, ten days after the Battle of Doirani, Bulgaria capitulated. It was followed on October 30 by the Ottoman Empire in Mudros. Austria-Hungary found itself in political turmoil due to the advance of the Allied Army of the East and lost its internal cohesion. The Dual Monarchy finally suffered a crushing defeat in the field on 24 October and capitulated on 3 November. Finally, Germany, in light of developments on the war fronts, collapsed politically and capitulated on November 11, 1918. On the same day, d'Espret was informed of the end of the offensive. The hammer had struck the anvil. The Great War had ended and the beginning of the end had begun on the Macedonian Front.

SOURCE:DIS/GES