The regular army of the revolutionary Greece is to a large extent an unknown parameter of the struggle of our national palligenesia, since the disorderly units of the fustanelo wearers have monopolized the attention of the researchers. And yet, even then, little Greece had a regular army, and indeed a particularly valuable one, and above all a fighting one, as far as the rulers allowed, at least.

The beginnings of the formation of the Greek regular forces can be sought in the heat of the Napoleonic Wars. Thousands of Greeks served under the flags of the European powers and were glorified on the battlefields.

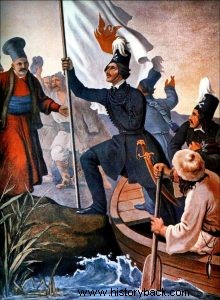

With the outbreak of the revolution in Moldo-Wallachia, Alexander Ypsilantis, an officer of the Russian Army and himself a hero of the battle of Leipzig in 1813, spread the need to form a regular army. The result of this was the formation of the Holy Society. After the disastrous battle at Dragatsani, his brother Dimitrios Ypsilantis managed to form a small tactical unit in the rebel Moria, which was joined by several survivors of the Holy Company.

Next was Alexandros Mavrokordatos who took over the organization of a regular division, but which was almost annihilated in the battle of Peta. After the calamity, order was re-established. But the government machinations and the civil conflicts that unfortunately followed did not allow him to become a man.

The situation changed after February 1825, when Ibrahim set foot in the Peloponnese at the head of strong regular Egyptian forces. The unruly Greek divisions had no hope of facing the Egyptians on equal terms in an expanded field.

Regular divisions had to be formed. Indeed, in July 1825 the French colonel Charles Faviero was given the command to form a regular army. Faviero, a glorious veteran of Napoleon's Grand Army, managed to impressively develop the Greek regular army.

At its peak, the Tacticon had four battalions of line infantry, three companies of cavalry – one infantry – a light artillery, a squadron of snipers and military music. This force numbered more than 4,000 men. Unfortunately, the indifference of the prisoners led to the dissolution of this wonderful department. When I. Kapodistrias arrived in Greece in 1828, the tactic did not actually exist.

The governor, from the first moment of his arrival, attempted and succeeded in reconstituting the Tacticon, but also in "ordering" the disorderly corps. His work was undone by his assassination. But why was Taktikon so valuable for Greece in those critical circumstances? Were the disorderly units not enough to deal with the Turks and then the Egyptians?

Capabilities of the season's regular divisions

In all the states of the "civilized" west at that time, the armies were now composed exclusively of regular divisions of infantry, cavalry and artillery. The divisions of all three of these arms fought in a specific way, based on military regulations. The infantry, the most numerous part of any army, initially followed the so-called linear tactics.

The experience of the Napoleonic Wars, however, forced all European armies, except the British, to drastically change their tactics. The French campaign regulation of 1791 was the model on which the corresponding European ones were based, except for the British one. The training of the Greek regular army was also based on the French regulation revised in 1818.

The regular infantry of the time had "reclaimed" the role of the king of battle. It was what he was claiming, but also holding the conquered ground. It was one that could easily deal with opposing cavalry, as long as it had the proper training and discipline. Armed with the classic front-loading musket, with a flintlock firing system, it had to gather a large number of men in a limited space in order to achieve the maximum possible destructive effect for the enemy. The musket was a weapon with very limited capabilities.

First of all, its effective range did not exceed 100 meters. Secondly, his rate of fire did not exceed four rounds per minute, by well-trained divisions. The usual combat rate of fire was on the order of two rounds per minute. For his basic defense, the pedestrian had another deadly weapon, the bayonet, the length of which was close to 50 cm.

A musket with a bayonet attached to its barrel was close to 2 meters in length – the average length of ancient Greek spears. Swordsmanship, however, was a more psychological than practical weapon. The threat of using it is what makes the opponent want to turn their backs and run away. This reality was fully understood by the Greek regular infantry, from 1825 to 1940-41.

The three battle formations

There were three main infantry battle formations, the line, the phalanx and the square. The line formation was the most appropriate in cases of defense against enemy infantry.

In the period of the 1820s the depth of the line reached three, or usually two even. The advantage of this particular formation was that it allowed an infantry division to use its full firepower against its opponent.

The men stood in a very dense formation, with the elbow of one resting on the shoulder of the man next to him. The men of the second yoke drew up about half a yard behind those of the first, and with their muskets sticking out between the heads of the men of the first yoke. The opponent was allowed to approach at a distance of about 50 meters. Then the department moved either collectively, or by division, against him with disastrous results.

The muskets, we must not forget, had a large caliber - 17 to 18.1 mm - and at such a short distance they could literally cut the opposing soldiers to pieces. In the event that the section was deployed in a line three scales deep, the third scale was not deployed and was either used to reload the weapons of the men of the first two scales, or was kept as a reserve of the section, or in the heat of battle was deployed in front of its front section in acrobolization arrangement.

Fire and motion

Captain Christos Byzantios, in his book "History of the Regular Army of Greece" of 1837, often mentions the use of a double - from the first two yokes (lines) - fire by the Greek regular infantry divisions.

In any case, the Turkish units facing them were either annihilated or fled in disorder. Courage and discipline, the products of hard training, were needed for a division to withstand the material, as well as the psychological consequences of a double fire, and the Turks possessed none of the above.

The second main infantry battle formation of the era was that of the assault phalanx. There were two types of phalanx formations, the phalanx by company and the phalanx by division, which was the most common. In the first case, a battalion of six companies, like the Greek ones, formed with a front of 50 and a depth of 18 men.

In the second case the battalion was deployed with a front of 100 and a depth of 9 men. The phalanx was the pre-eminent formation for approaching and executing an attack against defensively established enemy infantry or artillery, but also sometimes against cavalry. The disadvantage of this particular formation was that it presented a large target for enemy fire and especially for artillery.

In the case of Greece, however, fortunately the Turks did not have sufficient field artillery. On the other hand, the main advantage of the phalanx was its agility and speed. A well-trained infantry division was capable of supplying at a rate of 120 steps per minute.

The phalanx was also a formation for exerting "psychological" pressure on the opponent. Any undisciplined section was unlikely to stand up to the onslaught of a moving forest of lances on a sprawling field.

Against infantry, but also cavalry...

Thus in the battles around Keratsini, in 1827, the attack in phalanx formation of just 280 Greek regular infantry, under Major Inglezis, was enough to break up a large Turkish body. At least 500 Turks were killed in this conflict, within a few minutes and with minimal Greek losses. But even more valuable was the achievement of the regular Greek infantry against the famous Turkish cavalry.

In the battles of Haidari, in 1826, the regular infantry, after repelling the advances of the Ottoman cavalry, counterattacked against it, in a phalanx formation, and put it to flight. In one skirmish he attacked again in a phalanx formation and overthrew an enemy artillery. This is how Chr. Byzantium the attack of the Second Infantry Battalion against the Turkish positions:

Battle pattern…

"Then Favierus, having agreed again after Karaiskakis, after placing the artillery opposite the enemy's neighborhood of the enclosure, moved with his army against the enemies. And the Second Battalion, under the command of Major Pissa, ordered to march in support in a thick phalanx towards the eastern part.

"He took the First Battalion, and formed it into a thick phalanx, he separated the Philhellenic company and that of the apostolics (infantry acrobolists horsemen) on the sides of the phalanx as acrobolists, and so with weapons at arm's length and with marching steps they attacked from the meridian part of the enemy at the moment, the infantry and cavalry of the enemy intensified their attacks against the light (disorderly) troops so much, that with all the skill with which the Greeks repulsed it, it was impossible for them to withstand a fleet of defenses.

"Firstly because they were not fortified, and secondly because the enemy's artillery also harassed them greatly. However, the light soldiers, when they saw the support (regulars) marching against the enemy without hesitation, and indeed against the enemy's cavalry and artillery, received such bravery and courage that, advancing from their positions, they attacked the enemy's infantry, which was immediately routed you're gone And the phalanx continued its anti-artillery course, although this did not stop the downward firing with pellets (bullet-bearing projectiles), in the meantime it was also defended by a large number of cavalry.

"But the battalion marched so fearlessly against the fire, that the enemy were forced to leave all munitions of war and retreat disorderly. Thus the Second Battalion pursued with this success the other enemy squadron, although instead of attacking the enemy with a marching step, it attacked them with an offensive step (attack step)".

A third battle formation of the era was the well-known square. The square could be either "open" or "closed". The open square was so called because its interior was open, i.e. it was not covered by soldiers. The closed square was an extremely dense formation, something between a phalanx and a square, better known as a mass.

The Greek regulars, following the French regulation, had been trained in the formation of open squares. The square formation ensured all-round defense. It was mainly used to counter cavalry charges, so that the infantry division that formed it did not present an exposed flank to the opposing cavalry. On occasion, however, it was also used to deal with raids, mainly by unruly infantry units.

In a square formation, the Holy Company fought against the Turks in Dragatsani and held off the eightfold Turks for a long time. On the contrary, in the battle of Peta, part of the regulars and the company of the Philhellenes, were surrounded by the ranks of the unruly Turks and after forming a square, they fought until the end, taking hundreds of Ottomans with them.

Organization

At this point, reference must be made to the organizational model of the Greek regular forces. The Holy Company of Al. Ypsilantis was organized as a line infantry battalion, with a force of five rifle companies ("central" companies). The regular regiment that took part in the battle of Peta was also organized into two battalions, each of five central companies, a company of snipers (Philellenes) and a company of escort artillery (two guns).

Only after Faviero took over the command did the Greek regular battalions exactly follow the existing European organizational model. Each battalion had, according to the French regulation, six companies. Four of them were rifle companies (center), one was a company of selectmen-grenadiers (right flank company) and the last one was a company of euzon-acrobolis (left flank company).

The skirmisher company usually lined up in front of the battalion front at a distance of up to 200 meters from it. The skirmishers formed the advanced line of defense of the battalion, during the defense, or the first echelon of its attack, during the attack. The company of grenadiers was either deployed as a support echelon of the snipers, or as a battalion reserve. When the battalion defended the snipers and grenadiers started the battle and gradually converged on the two ends of the battalion. The French, Prussian and in parts the Austrian army of the time fought in exactly the same way.

Cavalry and artillery

As for the Greek regular cavalry, this at its peak consisted of a legion of spearmen, a legion of mounted hunters, and a legion of infantry, lacking horses, a legion. The father of the Greek cavalry was the Portuguese Almeida, also a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. Of course, Al.Ypsilantis was the first to form regular cavalry in Moldowallachia. The cavalry division of Ypsilantis, however, under the command of the rather mediocre B. Karavias.

Dressed in Russian uniforms of Cossacks and hussars, the approximately 100 regulars - with them also fought approximately 800 irregulars - horsemen were disbanded, the fault of their leader, in the battle of Dragatsani. Almeida's cavalry, on the other hand, was to thrive and form the core of the Cavalry-Armoured weapon. Although Almeida never had more than 160 mounted warriors at his disposal, he nevertheless trained them and made the best use of them.

Due to their small numbers, the Greek horsemen were trained in ilis tactics only. Nevertheless, the Greek ilarchy (two islands) also acted in concert when needed. At the end of the summer of 1825, the hilarchy led by Colonel Almeida was patrolling the plain of Milos in Argolis. During the patrol he spotted a regular Egyptian battalion of Ibrahim's army.

Immediately Almeida ordered his men to form a line of two yokes and fall upon the Egyptians. The latter had also seen the Greek cavalry taking up positions to launch an attack and hastened to form a square. But they didn't make it. The rapid advance of the Greek horsemen "broke the yokes" of the Egyptians.

The soldiers lost all organic ties and fled independently, only to be cut down by the spears and swords of the Greek horsemen. More than 400 Egyptians were killed, without any Greek loss.

Artillery was the third weapon of the regular armies of the time. In revolutionary Greece, however, there were no possibilities for its development. At best the regular army was found to have only an artillery of four light guns. But these too often became unusable due to faults, which were not easy to overcome, due to the lack of technical means.

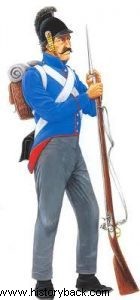

Regular soldier in the uniform of 1825. He wears a distinctive helmet made of hardened leather, a musket and a bayonet. Design by Stelios Nigdiopoulos.

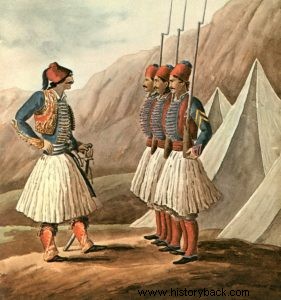

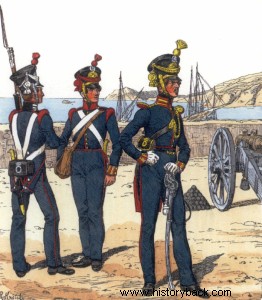

Soldiers of a light tactical division. These sections began to be formed after the arrival of Kapodistrias and mainly under Othonos.

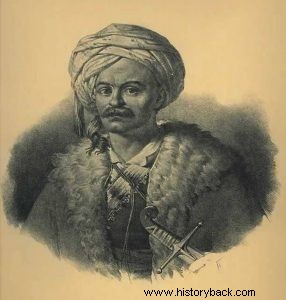

The French colonel Karolos Favieros, a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, came to Greece in 1824 to support the revolution. He undertook the formation and administration of the Regular Corps, but was disappointed many times by the iniquity and stupidity of the prisoners. He left Greece after the assassination of Kapodistrias.

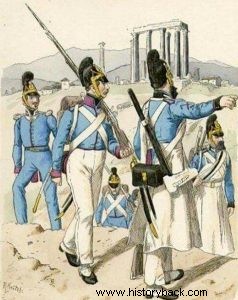

Bavarian soldiers who accompanied Otto to Greece. Ήταν οργανωμένοι όπως και το ελληνικό τακτικό σώμα και έφεραν παρόμοιες στολές.

Ο Αλέξανδρος Υψηλάντης περνά τον Προύθο ξεκινώντας την Ελληνική Επανάσταση.

Έλληνες πυροβολητές επί Όθωνος.

Ελληνικό ιππικό επί Όθωνος.

Αναπαράσταση βρετανικού ανοιχτού τετραγώνου στη μάχη του Βατερλό.

Ο Πορτογάλος βετεράνος των Ναπολεόντειων Πολέμων και «πατέρας» του ελληνικού τακτικού ιππικού Αντόνιο Αλμέιντα.