Reading, or rather, re-reading Manzoni in a Keynesian key and take his criticisms of the way in which the government of Milan, in the betrothed , handled the bread crisis, the result of a deeper agrarian crisis, as a criticism of state intervention on the free market , means not having understood anything of Manzoni, of his thought and of his work. Also because, the crisis that hit Milan did not affect other cities in which similar decisions were made.

The central theme in the Betrothed

The entire Manzoni novel revolves around a key concept, one, fixed, immobile and immutable, which transpires from every word, from every sentence, from every event and dynamic told in the book, and is the critique of traditional society , the critique of feudal society , which, in the late nineteenth century, still survived in Italy, in an unnatural way.

Manzoni believes in the values of the historical right, he is a classic liberalist who, like John Loke, believes in respect for individual rights, and is strongly convinced that these rights must be guaranteed by public authorities, for Manzoni, the state must intervene in defense and protection of those rights considered natural and universal.

Manzoni sets his novel two centuries earlier, in the middle of the 17th century, when the whole world was still totally immersed in feudal society, to highlight the same theme raised by Giuseppe Tommasi di Lampedusa in the Gattopardo and Carlo Levi in Christ stopped at Eboli , the latter more than a century and a half later than Manzoni. And it is the theme of the social static nature of Italy, of an immobile and immutable Italy in which the elites change, the crowned heads change, the systems and balances change, but in reality nothing ever changes and the peasants and popular masses, who Manzoni in his novel recognizes as early as the seventeenth century, living a condition of subordinate class whose interests are marginal for the politics and society of the time, if they represent the majority of the population.

Manzoni looks to those years in which the world would have known one of the first great bourgeois revolutions in history, the English Revolution, and he does so as a man of the 19th century, Manzoni writes at the beginning of the 19th century , he writes after the French Revolution , he writes after Napoleon and after the restoration , and tells of a world immediately preceding the first Enlightenment instances , the first claims of universal rights, and despite two abundant centuries have passed, despite the revolutions that have taken place in Europe and outside Europe, such as the American and French revolutions, despite Napoleon, nothing really seems to have changed, not in Europe at least.

Manzoni is not an absolute promoter of the free market, he is not a supporter of laissez fair and of the absent state, Manzoni is a liberal and monarchist conservative and does not criticize Milan who sets the price of bread, for the intervention on bread, because, Manzoni does not tell the global market in the 2000s, and reasoning in terms of global economy thinking of Manzoni, is crazy and anachronistic.

Manzoni talks about a closed world and talks about the bread supply chain , in a limited area, represented by the countryside around Milan, in the 17th century . And it is an extremely poor, primitive and limited supply chain .

Manzoni tells of a world in which farmers don't buy bread who live in the countryside, they make bread at home, with the flour they have obtained by grinding cereals by hand or which they have traded for cereals with the miller.

Certainly it is not the nobles and landowners who buy bread , the bread for them is produced in the kitchens of the buildings, it is produced with the wheat and flour of the rents, we are in the seventeenth century, there are no debt collection agencies, we are in a world where taxes and land rent are more or minus the same thing and are collected door to door by the collector who knocks and asks for money, and if the money is not there, and in the countryside there is no money, then the tax collector asks for wheat and flour, asks at least a tithe of the production.

Certainly it is not the millers who buy bread , the millers do not need it, they are few and they produce the flour for the ovens, in the miller's house there is never a shortage of bread, salami and cheese.

So who is it that buys bread in 17th-century Italy?

At the time of the betrothed, as well as at the time of Manzoni, it is the small and medium bourgeoisie who buy bread. , a social circle to which Manzoni himself belongs, are the merchants, blacksmiths, artisans, traders, innkeepers, intellectuals, they are the servants of the nobles and the upper middle class who buy it for their families, they are the popular masses living in cities and who, unlike farmers in the countryside, do not have direct access to food . They are men and women who in order to survive are forced to buy food, they are the children of urban modernity who depend on the market, they are part of the market, they are the basis of the market and as such, for Manzoni, they should be protected by state entities, but in 1628, this is not possible, this is not even thinkable, because the father of these ideas, John Loke, was born in 1632 and thinking about the world that precedes Loke, according to the canons dictated by Loke, represents the perfect definition of anachronism .

In the world described by Manzoni, and partly also in the world in which Manzoni lives, the bread supply chain does not make the price of bread, and believing that the price of bread depended on the cost of flour, which in turn depended on the cost of cereals, means not understanding the historical reality of the time and of the world described by Manzoni, thinking this means attributing to the farmer, the last link in the chain social in feudal society, enormous power, the power to decide the price of grain. It means re-reading the past in a modern way and superimposing today's mechanics on a world where these mechanics didn't exist.

Manzoni partly from this error, he does it voluntarily and for political reasons, he does it because the world he tells is not really the seventeenth century, but the nineteenth century disguised as the seventeenth, consequently the social dynamics and all the historical events present in the 'work are reinterpreted according to modern canons, and if this, from a narrative point of view can be interesting, from a purely historical point of view, it is anachronistic, because it distorts time and history.

Peasants in the 17th century they had no decision-making power on the price of cereals , on the price of grain, ne the miller had that power on the price of flour. The same cannot be said totally in the nineteenth century, where the peasants are no longer workers of the land and administrators of the fields, but are simple workers, especially in the countryside around Milan, and this was revealed about half a century later by the count Jacini, the peasants are real workers of the land, who are paid. In 17th century Milan, however, when the bread revolt broke out, the price of wheat, of flour, was determined by the baker and only by the baker.

Manzoni in the betrothed does not speak and does not mention the supply chain , not because he is distracted or because he has forgotten, he would have included a detail of this type if it had been relevant, but it is not, not in the seventeenth century at least, Manzoni has chosen not to include the bread supply chain in the book because he knows perfectly well that the economic dynamics that govern the supply chain in the seventeenth century are different from the mechanics of the nineteenth century and he also knows that in the seventeenth it is irrelevant in determining the final price of bread.

Not surprisingly, always in the Promessi Sposi, if on the one hand the cities are suffering from hunger, the countryside they are only marginally affected by the crisis. In the countryside the problem of the plague is marginal and the problem of the cost of bread does not exist, and this is precisely because in the countryside the farmers make bread themselves , and the poorest, even make the flour themselves, with small hand grinders that allowed them to grind dry cereals and make flour, a little flour, by rotating a stone disc in a stone bowl, or at most with rudimentary stone mortars and similar tools were present, since the early Middle Ages, in the homes of most of the peasants of Europe.

Telling Manzoni as a modern liberal , at the beginning of the 19th century, is certainly anachronistic, but not totally wrong, after all Manzoni was a liberal, a different type of liberal, but still a liberal who believed in the ideals of bourgeois society, Manzoni believes in the ideals of the historical right, which however is not to be confused with modern liberalism, the son of Keynes theories . Using the pages of the betrothed to draw some analogy with current events means distorting a work, it means distorting the historical reality it tells, already widely distorted by the author for a specific historical as well as political reason, it means decontextualizing that story and ignore everything that Manzoni has written, said and thought, totally disrespecting the work and the author.

In the betrothed the price of bread rises , it increases a lot, and as it increases it remains unsold, this is something that in the historical reality of the seventeenth actually happens, both in Milan and elsewhere, but there are also other areas of Italy and Europe where this does not happen, such as for example Naples, Rome, Florence, etc. etc.

By observing and analyzing what happened in those years, we can see that there is no single model, there are realities in which by fixing the price of bread, a revolt does not break out, and realities in which the price of bread does not increase, such as example in Naples.

In Naples in particular, and I quote Naples simply because it is the case that I know best, the crown supported a particular economic theory , in Naples and in the other big cities of the "kingdom", wheat should never be missing and indeed, during the seventeenth-century plague, wheat in Naples and other cities in southern Italy , did not fail and there were no major riots for bread, which may seem surreal if you think that Naples at the time was one of the largest megacities in the world , the third most populous city in Europe, second only to London and Paris, cities that had had several riots.

The crisis in Naples, and Manzoni is well aware of it, did not occur thanks to state intervention on the price of wheat and bread, set long before the crisis began, and the same happened elsewhere. Manzoni knows perfectly , and we contemporaries should also know that it was not the decision to fix the price of bread that triggered the bread crisis in Milan , that decision was made when the crisis had already begun and was not enough to stem it. to pretend that the revolt of bread is somehow connected to the blockade placed on the price of bread, is to confuse cause and effect. Blocking the price of bread, Manzoni tells us, was not the solution to the crisis, but not the trigger either.

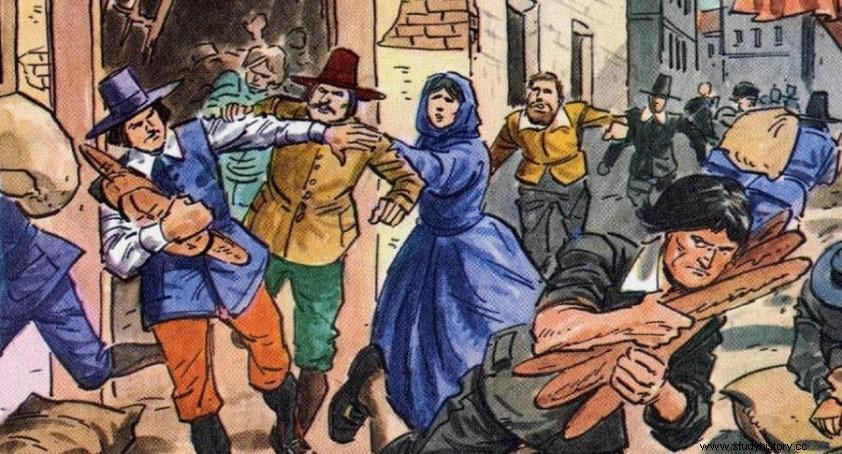

After all, we know that during the bread revolt , in November 1628, what happened was that the popular masses attacked the ovens and warehouses with flour, and stole bread and flour. The presence of huge reserves of wheat, bread and flour in the warehouses, in Milan and Naples, made production possible and sustainable, and with the same basic agrarian crisis, linked to the great mortality in the cities and in the countryside, caused by the plague, the bread continued to be baked, but, in cities like Naples, production does not stop, the price does not rise, and the bread is sold, in Milan instead, bread is produced despite the plague, but the price rises and consequently remains in largely unsold, which would normally cause the price of bread to drop, but this does not happen, unsold bread remains in the ovens for days, weeks, and this feeds the popular intolerance that, in the grip of hunger, rose up by attacking bakers and granaries.

The Jacini investigation

Shortly after the final Italian unification, in the seventies and early eighties of the nineteenth century, count Stefano Francesco Jacini , was placed at the head of an agricultural commission, with the task of studying and analyzing the situation of the Italian countryside at that historical moment, the commission produced a document, known today as Jacini inquiry (now freely available on the portal of the cultural heritage archive of the general directorate of cultural heritage), in which a map of the Italic agrarian structure was presented, the profile of the countryside, of the cities, of the distribution of peasants was defined, it also collects data on the evolutions and transformations of the Italian countryside in the last century, and in doing so he discovers that, starting from second half of the eighteenth century, different areas of Italy had adopted different solutions.

Naples had built large granaries and the Bourbon crown, from about 1772, had almost totally monopolized the purchase of wheat and cereals from the countryside around the cities, which was sold at a low and constant price to city ovens, as well as distributed through rations, to the poorest sections of the cities. At the same time, the countryside had not undergone many variations and the large estates continued to be, as in the past, the model on which the countryside was founded, controlled by a few nobles, and worked by masses of poor but rarely hungry peasants.

Milan and Lombardy, on the other hand, had undergone, in the last century, a process of subdivision, which had led to the birth of a peasant petty bourgeoisie, in which the peasants were no longer tenants, but owners, this autonomy had partly enriched them but at the at the same time, he had removed them from the earth.

Jacini, in his investigation notes that most of the landowners of the area around Milan, did not live in the countryside but in the city, and the work of the land had been entrusted to salaried peasants, this transformation particularly characterizes the first half of the nineteenth century. century, and draws a map of the Milanese countryside that is profoundly different from two centuries earlier, nevertheless, the social dynamics are unchanged. The peasant petty bourgeoisie, some historians would have observed, relates to the peasant masses, according to the ancient schemes, of feudal society, with the difference, compared to the past, that the bulkheads that separated the social classes were now exclusively economic, and did not have no longer any dynastic connotations.

Conclusion

Reading today, the revolt of the bread of milan of 1628, told by Manzoni in 1827, in a modern liberal key, is wrong and anachronistic, because one makes the mistake of reinterpreting the thought of a man of the nineteenth century who in turn reinterprets facts of the seventeenth century. Furthermore, this liberal reinterpretation of Manzoni appears even more fallacious if we look at it without considering what emerged from the Jacini investigation at the end of the nineteenth century.

The world that Jacini describes is the world in which Manzoni lives, and Manzoni while the world that Manzoni describes, is the ancient world, a world that partially survives in northern Italy, and more deeply rooted in southern Italy, but it is a world at sunset and close to collapse, Manzoni knows or at least hypothesizes that that world is about to end, Manzoni knows the popular discontent, he knows well that Europe is in turmoil, and if he does not know exactly what is about to happen, he perceives the tension that at the outbreak of new revolutions shortly thereafter, Manzoni is immersed in history and frequents specific environments in which liberal ideas circulate.

Alessandro Manzoni is a man of the nineteenth century, who reinterprets the seventeenth century by covering it with the social dynamics of the nineteenth century, and so far, everything is ok, we forgive Manzoni because he himself gives a very specific motivation for his narrative choice.

Manzoni's story is not anachronistic, his is fiction that makes social and political criticism using a narrative ploy.

On the other hand, what is not good, and falls within the problem of anachronism, is to take Manzoni's nineteenth-century narrative, to pretend that that reworked narrative is a historical reality and to compare it with the twenty-first century.

If we want to talk about the Milan bread revolt of 1628, we must evaluate the facts for what they are, and not on the basis of the narrative revised by Manzoni.

If, on the other hand, we want to talk about the agrarian question in the nineteenth century, I recommend Corrado Barberis's book, The Italian countryside from the nineteenth century to today.

Bibliography

A. Manzoni, I promessi sposi.

C. Barberis, The Italian countryside from the nineteenth century to today.

C. Barberis, The Italian countryside from ancient Rome to the eighteenth century.