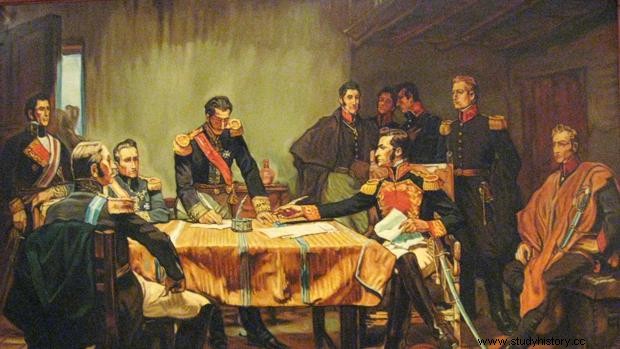

Capitulation of Ayacucho, oil painting by the Peruvian painter Daniel Hernández. To subdue Peru, the joint action of the forces of Bolívar and San Martín was necessary. Thus, it was only in July 1821 that Viceroy José de la Serna ordered the evacuation of Lima, giving San Martín the freedom to proclaim the independence of Peru. And the capital would still change hands several times until, with the Spanish forces at the limit, came the battle of Ayacucho and with it the defeat of the most important royalist military contingent that was still standing.

Capitulation of Ayacucho, oil painting by the Peruvian painter Daniel Hernández. To subdue Peru, the joint action of the forces of Bolívar and San Martín was necessary. Thus, it was only in July 1821 that Viceroy José de la Serna ordered the evacuation of Lima, giving San Martín the freedom to proclaim the independence of Peru. And the capital would still change hands several times until, with the Spanish forces at the limit, came the battle of Ayacucho and with it the defeat of the most important royalist military contingent that was still standing.In parallel to the events of Ayacucho, there was still one last garrison that undertook an almost suicidal resistance. José Ramón Rodil y Campillo and the last Spaniards in Peru barricaded themselves in the Fortress of Real Felipe del Callao, initially built to defend the port against attacks by pirates and corsairs.

A modern Leonidas in Peru Lima and the fortress in Callao had been recovered by the Spanish months before the Ayacucho disaster, coinciding with one of the few periods of the war favorable to royalist interests. General Monet at the head of the royalist forces had entered the capital again on February 25, 1824 and appointed Brigadier José Ramón Rodil as head of the Callao garrison. He did it, of course, without suspecting that this Galician officer was going to lead an epic resistance. Lima was abandoned after the battle of Junín. The Spaniards in Callao were expected to take the same path after the capitulation of Ayacucho, but Rodil and his 2,800 soldiers refused to surrender on the prospect that they might soon receive reinforcements from Spain. Rodil even refused to receive envoys from the Viceroy la Serna, defeated in Ayacucho, because he considered them little less than deserters. He also did not want to listen to the representatives of Simón Bolívar on December 26, who took it for granted that the Spanish would surrender the fortress as soon as he learned of the generous terms of the capitulation.

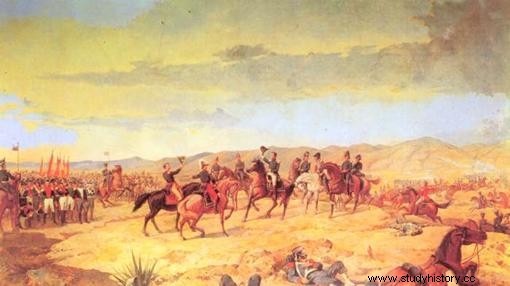

Oil painting of the Battle of Ayacucho, a work by Martín Tovar y Tovar The Galician believed that his was a journey with no turning back. Bolívar's entry into Lima caused the massive flight of the population of peninsular Spaniards and of those loyal to the Crown towards Callao. 8,000 refugees turned Callao into the last Spanish stronghold in South America and the last hope of recovering these territories. The siege of the liberating troops, some 4,700 soldiers, led by the Venezuelan Bartolomé Salom, began in the form of heavy artillery bombardment of the port of the walled enclosure. It is estimated that in the two years that the siege lasted, 20,327 cannonballs, 317 bombs and countless bullets were fired. To the air and land attack, the naval blockade of the combined fleets of Gran Colombia, Peru and Chile was also added. Despite having fewer armed men and few resources, the Spanish had several things in their favor. José Ramón Rodil had among his ranks the veteran regiments Real de Lima and Arequipa, as well as one of the largest fortresses in the entire continent. The walls and mines embedded in the rock made a ground assault impossible, while the artillery bastion kept the combined fleet at a distance.

Oil painting of the Battle of Ayacucho, a work by Martín Tovar y Tovar The Galician believed that his was a journey with no turning back. Bolívar's entry into Lima caused the massive flight of the population of peninsular Spaniards and of those loyal to the Crown towards Callao. 8,000 refugees turned Callao into the last Spanish stronghold in South America and the last hope of recovering these territories. The siege of the liberating troops, some 4,700 soldiers, led by the Venezuelan Bartolomé Salom, began in the form of heavy artillery bombardment of the port of the walled enclosure. It is estimated that in the two years that the siege lasted, 20,327 cannonballs, 317 bombs and countless bullets were fired. To the air and land attack, the naval blockade of the combined fleets of Gran Colombia, Peru and Chile was also added. Despite having fewer armed men and few resources, the Spanish had several things in their favor. José Ramón Rodil had among his ranks the veteran regiments Real de Lima and Arequipa, as well as one of the largest fortresses in the entire continent. The walls and mines embedded in the rock made a ground assault impossible, while the artillery bastion kept the combined fleet at a distance.Likewise, the seniority of his commander played in favor of the royalist forces. Born in Lugo on February 5, 1779, Rodil had fought against Napoleon and then jumped to South America, where he rendered important services in Talca, Cancharrayada and Maipo. In addition to scars, the Galician collected multiple decorations for the courage displayed. Without the possibility of sinking a tooth into the fortress, the liberating armies kept up the bombardment day and night in an attempt to let the fruit fall under its own weight. From the beginning, the difficulty of feeding a civilian population of thousands of refugees became latent, as well as maintaining an almost prison regime to prevent desertions among the Spanish ranks. In a single day, Rodil shot 36 conspirators, among them an Andalusian boy who was very popular because of his pranks.

José Ramón Rodil, commander of the Callao garrison. In a report dated September 26, 1825, Hipólito Unanue wrote to Simón Bolívar about the state of the siege, which had become a prison both inside and outside the fortress:«Rodil continues to defend himself stubbornly and not a day goes by without strong fire being fired at the. For its part, it has enormous vigilance and as soon as it sees that someone from the town passes or that work has been done on the line, when it covers the site with bullets, so many who want to do it do not get scared.

José Ramón Rodil, commander of the Callao garrison. In a report dated September 26, 1825, Hipólito Unanue wrote to Simón Bolívar about the state of the siege, which had become a prison both inside and outside the fortress:«Rodil continues to defend himself stubbornly and not a day goes by without strong fire being fired at the. For its part, it has enormous vigilance and as soon as it sees that someone from the town passes or that work has been done on the line, when it covers the site with bullets, so many who want to do it do not get scared.The enemies were famine and epidemics Famine, poor sanitation and epidemics grew at the same rate that rat meat skyrocketed in price on the black market. That is why Rodil sent those civilians whose presence was not important in the military field to the enemy front. Faced with this strategy, the liberators began to repel the waves of civilians with lead and gunpowder, knowing that hunger was the best weapon to get the Spanish out of their castle. Many refugees were caught between the two fires. Only about 25% of the civilians managed to survive the two-year siege. Scurvy, dysentery and malnutrition were reducing the number of defenders each day of resistance. Not so the determination of Rodil, who only agreed to surrender when the situation took on an extreme atmosphere. In early January 1826, Royalist Colonel Ponce de León defected, followed shortly after by Commander Riera, governor of one of the fortified sections, the Castillo de San Rafael. Both knew in detail the defensive framework established by Rodil and thus revealed it to the liberating leaders. Ponce de León, moreover, was a close friend of Rodil, which meant a double betrayal. Without food, with ammunition close to running out, and with no news that reinforcements would arrive from Spain; Rodil agreed to negotiate with the Venezuelan general shortly after the illustrious defections. On the 23rd of that month, after two years of resistance, the Spanish handed over the fortress in conditions that allowed the defenders to preserve their honor and life. Or at least the survivors. Only some 376 soldiers managed to survive those two extreme years, saving the flags of the Royal Infante regiments and the Arequipa Regiment.

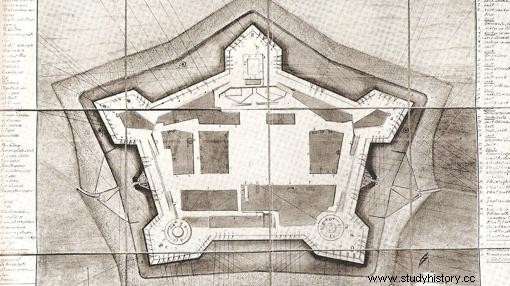

Plan of the fortress of Real Felipe, in Callao Rodil's life was also respected, among other things because Bolívar himself came out in defense of the Spaniard:"Heroism is not worthy of punishment."

Plan of the fortress of Real Felipe, in Callao Rodil's life was also respected, among other things because Bolívar himself came out in defense of the Spaniard:"Heroism is not worthy of punishment."The return of "a pure beast Spaniard" Spain had forgotten the last defenders of South America when they were fighting, but when they returned to the peninsula some of them were rewarded for their deed. José Ramón Rodil was appointed Field Marshal and in 1831 he was awarded the noble title of Marquis of Rodil for his performance in Peru. However, his status as a strategist was called into question by several defeats in the First Carlist War. His political career ended as a result of his antagonism with Baldomero Espartero. In 1815, Espartero sponsored Rodil to be tried by a court martial and his honors, titles and decorations were withdrawn.

What motivated his obstinate resistance to Callao?, his detractors continue to ask today. The late Peruvian politician Enrique Chirinos quoted, in one of his historical works, a well-known verse to define him:he was "a pure Spanish beast." That and that he really trusted, until the summer of 1825, that a reconquest force would be sent from the Peninsula. Controlling that strategic position was key to having a landing point in America. When he realized that help would never come, he stopped sleeping and barely ate, fearing, perhaps, that all his efforts would ultimately be in vain.

SOURCE:http://www.abc.es/