Historiographically, the year 476 AD is considered. like that of the end of the Western Roman Empire, being its last emperor Romulus Augustulus. It was not something that happened suddenly but rather as a result of an evolutionary process that began centuries ago, throughout which Rome suffered a progressive weakening for multiple reasons, some external and others internal, some general and others specific. And although the legions were not immune to these changes, they made an effort to defend that dying light of civilization until the last moment, starring in what we can consider their last battles.

Since the second half of the 4th century, a new system of relationships had been formed that was based on the closed rural economy, in an almost independent town, very different from the old slaveholding estate and that constituted the first step towards a new figure, that of the fief. That had effects on the colonato (slavery tended to disappear as it cost more than it produced), whose members, middle and lower class, used to exercise great mobility to avoid tributes and found in those mini-states a good way to avoid imperial collectors.

To prevent this, the state enacted measures that linked them to the land, which had repercussions in a transformation of the cities:they became fortified to the detriment of trade and its fall dragged slavery because, as there was no market for the products, it cost more than it produced. In turn, this curbed monetary activity in favor of payment in kind; the latter was extended to soldiers, who, except for those of a certain rank, began to receive part of their salary in goods. In fact, they too were assimilated into a relationship of servitude, especially in border areas, giving rise to private units (generally mounted, called bucelarios).

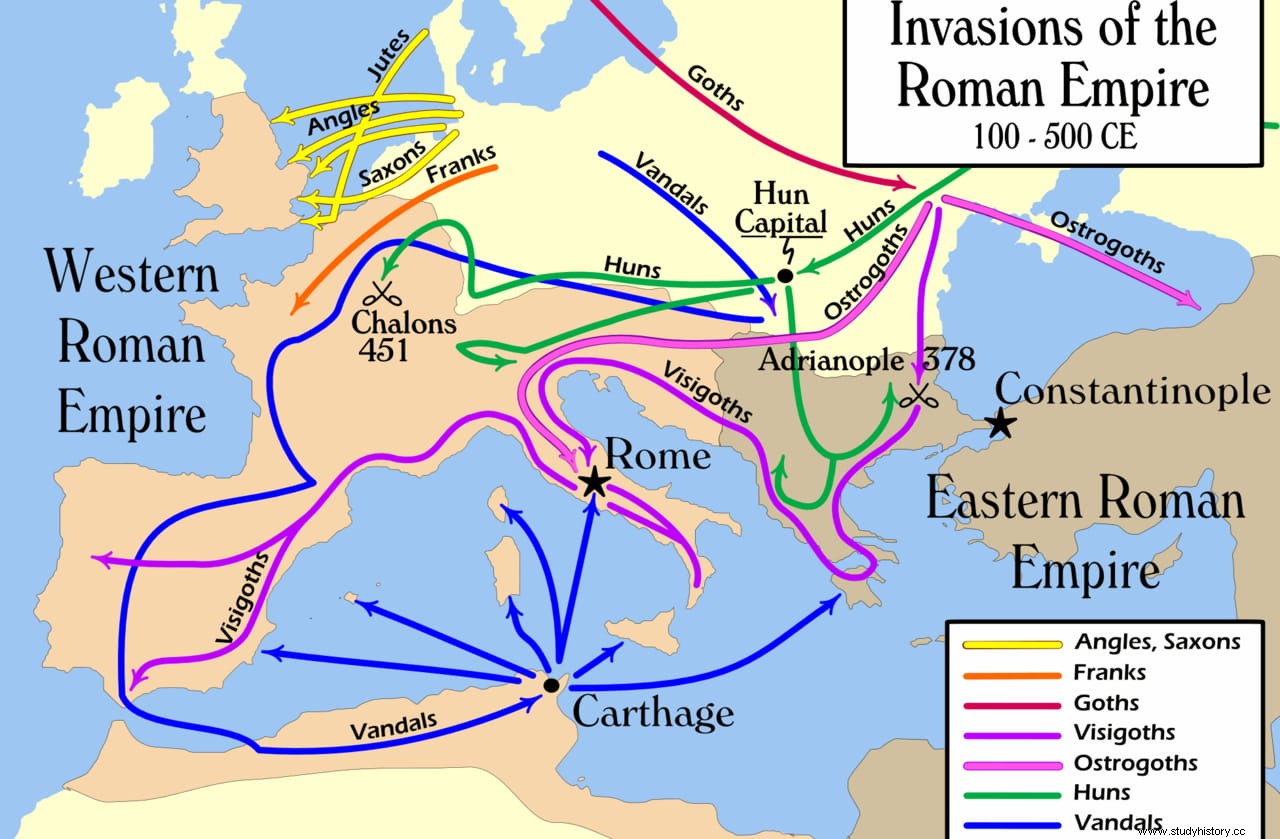

The army could not avoid reforms either, giving entry to the barbarians, especially in the limes , which implied two things:on the one hand, the difference between border troops and the local population was blurred; on the other, those in charge of defending the empire from external threats did not see them as such and, in fact, outsiders often ended up receiving a license to settle in imperial territory under the formula of foedus . Thus, the late Roman legionnaires were subject to their commands by relations of servitude, which brought them closer to the medieval world than to the classical one and limited both a coordinated defense and the available resources.

They had also undergone changes in their equipment, Germanizing it:the segmented helmet was imposed over the galea, the chain mail over the plate cuirass, the circular or oval shield over the tiled one, the spatha about the gladius and the long spear on the pilum , the latter in accordance with the recovery of the phalanx formation. They were adaptations that, despite what is believed, did not reduce their operability or their effectiveness and only at the end did the army begin to be overwhelmed, often undermined by the very instability of the empire, involved in internal wars, and the insufficiency of funds, a result of what was described above, which prevented the availability of adequate replacements.

Even so, the Roman army continued to fight until it had its swan song in a series of battles that marked those last years. Obviously, not all of them can be reviewed, so let's briefly see the most outstanding of the 5th century AD.

Catalaunian Fields (451 AD)

Flavius Aetius is often called the last Roman and can certainly be considered the pillar on which the Western Roman Empire stood in its final stage. He was a military genius who had come to prominence in 427, with a two-year campaign in Gaul that curbed the growing importance of the Franks and Visigoths. He was only thirty-one years old at the time, but his victories at Arelate (Arles) and Narbonne earned him the position of magister militum , following after his unbeaten performance elsewhere.

The list of his defeated enemies includes Huns, Burgundians, Franks, Vandals, and Visigoths. But also Roman adversaries; for example, General Bonifacio, with whom he disputed the favor of Gala Placidia, mother (and regent) of the future Valentinian III, ending in civil war. He won her over, of course, becoming the strongman of Rome and right-hand man to the emperor for the next two decades. And at that time he claimed one of his most notorious triumphs:the one that confronted the Huns in the Catalaunian Fields (current Chalons).

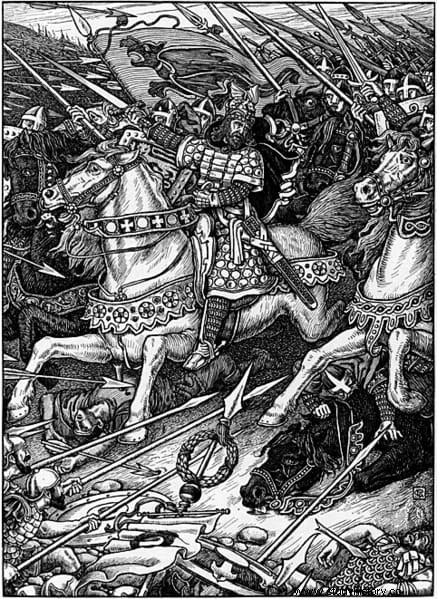

At the head of an alliance with the Visigoth Theodoric I and other peoples (Franks, Alans and Burgundians), his troops went out to meet those of Attila in Gaul, a territory that he intended to seize after looting several of his cities. . The Huns were not alone either, as they were accompanied by forces from vassal kingdoms such as the Ostrogoths, the Heruli, etc. It was, therefore, a large-scale clash that, although it actually ended in a draw, is usually considered a Roman victory because it meant the withdrawal of the Huns… although with it they would change their objective and invade Italy. Aetius, by the way, died successfully:Valentinian thought he had become too powerful and had him assassinated three years later; the emperor was also struck down twelve months later, while his guard, made up of loyal to Aetius, did not lift a finger to prevent it.

Orleans (463 AD)

It is curious that the looting of Rome by the barbarians in the years 405 and 455 were carried out practically without the need to have previously defeated it in battle. In any case, the new emperor, Avitus, decided to avoid further surprises by negotiating with the Visigoths, because after all, his king, Theodoric II, had helped him ascend the throne. However, neither he nor his policy of appeasement were popular and he ended up deposed by General Mayoriano, who took his place until he himself was assassinated by Flavio Ricimero, the strong man of Rome, who put in his place Libio Severo (he he could not proclaim himself because he was German by origin).

Ricimer, who we have already discussed in another article, was opposed by a former protégé of Majorian, General Egidio, who did not recognize Severus and proclaimed himself independent in northern Gaul -of which he was magister militum – supported by the Franks, threatening to march on Rome. Cleverly, Ricimer arranged for Theodoric II to meet him by opening the possibility of extending the Visigothic kingdom beyond the Loire. The clash took place in Orleans, ignoring the size of the contenders' forces, the number of registered casualties and how the battle unfolded. But the Visigoths were defeated and their leader, Federico, brother of Theodoric, lost his life.

Sea Battle of Carthage (468 AD)

The Vandals abandoned the Iberian Peninsula in 429, when the emperor handed it over to the Visigoths as foederati (as before them) and settled in what are now Tangiers and Ceuta, later expanding throughout North Africa and establishing the capital of their new kingdom in Carthage. In 468, fed up with their raids, the emperor Majoriano had carried out a punitive operation against them that resulted in the battle of Cartagena, ending with a naval disaster for the Roman fleet. Thirty-nine years later, the Eastern Emperor Leo I decided to solve the problem with an invasion that, incidentally, would avenge the sacking of Rome by the Vandal King Genseric in 455.

For this he assembled a fabulous fleet, made up of just over a thousand ships in which he embarked ten thousand soldiers under the command of his brother-in-law, the doge Basilisk. He had the collaboration of the Western Emperor Artemio and General Marcelino, who governed the province of Iliria. The latter fulfilled his mission of conquering Sardinia and Libya, then joining his forces with those of Basiliscus to advance on Carthage and send Genseric an ultimatum. The Vandal leader asked for time to negotiate the conditions and thus was able to take the attackers by surprise, sending them dozens of fire ships (flaming ships filled with combustible materials) that caused a catastrophe in the invading fleet, causing it to lose half of its troops.

Genseric's victory provoked some -for him- surprising, suspected and welcome consequences:faithful to his time, the defeated Roman leaders dedicated themselves to exterminating each other; only Basilisk was saved but he was banished.

Soissons (486 AD)

Gaul was once again the scene of a battle at this time, this time between the former Roman and Frankish allies. Egidio's successor, Afranius Siagrius, ruled as dux that independent territory with its capital in Novidunum (current Soissons) that extended between the Meuse and Loire rivers, but the Salian Franks (from the Rhine area, current Netherlands and Germany), led by Clovis I, were in full expansion towards the west and they were not going to stop, so it was already the last bit of power in Rome (Romulus Augustulus had been deposed by the Herulian leader Odoacer in the year 476).

Clovis managed to bring together various Frankish peoples and in a boastful display put the city of Soissons as a point of confluence. Later it was shown that it was not petulance but reality:Siagrio, defeated, had to gallop away and ask for protection from the Visigoths of Alaric II... who did not forget that his father had crushed them two decades earlier. And if they forgot, Clovis warned them that the Kingdom of Tolosa could be his next target, so Siagrio and his court were executed. The Roman Empire also disappeared from Gaul, giving birth to the Frankish Kingdom.

Mount Badon (490-517 AD)

Mons Badonicus It was the name of a mountain of indeterminate location although located in Britannia. There, on an unspecified date, a battle was fought between Briton-Roman forces and Anglo-Saxon raiders about which there is hardly any information, except that they came from the north. In fact, as is often the case at that time and place, everything is very dark and only the work De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the ruin and conquest of Britannia), by the native cleric Gildas, sheds a little light without specifying too much (although being contemporary with the events gives it some credibility). Here too we do not know how many forces were at stake, but we do know that the defenders were the last Roman remnant on the island after Constantine III ordered their abandonment at the beginning of the 5th century.

According to Gildas, the supreme command of the army fell to Ambrosio Aureliano, an aristocratic and Christian general who has often been identified as the character who originated the legend of King Arthur and whose historicity is confirmed by other sources, as in the case of the Britonum History . We do not know if Aureliano personally led the troops in the battle or delegated to some subordinate; we do know that the South Saxons of Aelle of Sussex (founder of the homonymous kingdom) faced several cohorts entrenched on Mount Badon and a contingent of Sarmatian cavalry. Surprisingly, given their numerical inferiority, the latter triumphed, stopping the Saxon raids for a time.