The independence of Peru has an official memory and calendar that puts San Martín in the center of everything Although July 28 was established early as the official independence day, it was not the only one. In 1833, President Agustín Gamarra promulgated a decree to annually commemorate the battles of Junín and Ayacucho on August 6 and December 9, 1824, "as part of the memorable events of our emancipation." Gamarra thus sought to highlight the participation of the Peruvian army, of which he was a part, in achieving independence. Significantly, and although perhaps Gamarra did not intend it that way, this celebratory plurality also enhanced the place of the southern and central Andean highlands in the process of independence. But despite the continental scope of the battle of Ayacucho, which is recognized worldwide as the definitive milestone of Hispanic-American independence, the multiplicity of celebrations gradually faded from the official calendar to highlight, if not exclusively, then centrally, the proclamation of San Martín in Lima.

The independence of Peru has an official memory and calendar that puts San Martín in the center of everything Although July 28 was established early as the official independence day, it was not the only one. In 1833, President Agustín Gamarra promulgated a decree to annually commemorate the battles of Junín and Ayacucho on August 6 and December 9, 1824, "as part of the memorable events of our emancipation." Gamarra thus sought to highlight the participation of the Peruvian army, of which he was a part, in achieving independence. Significantly, and although perhaps Gamarra did not intend it that way, this celebratory plurality also enhanced the place of the southern and central Andean highlands in the process of independence. But despite the continental scope of the battle of Ayacucho, which is recognized worldwide as the definitive milestone of Hispanic-American independence, the multiplicity of celebrations gradually faded from the official calendar to highlight, if not exclusively, then centrally, the proclamation of San Martín in Lima.This decision had another paradoxical effect. Setting the Lima proclamation of San Martín as the central commemorative milestone of independence made the independence process itself invisible, that is, the insurgent and separatist movements that occurred in different parts of Peru prior to the arrival of the River Plate general. We Peruvians, therefore, build an official memory of independence as a quasi-providential process, coming from outside and even tinged with dreamlike elements, like when children are taught that the Peruvian flag originated in a dream of San Martín! ! In this sense, we are a continental anomaly:we chose a late moment, a milestone moment comparatively devoid of insurgent charge, as well as propitiated from outside, to commemorate our independence.

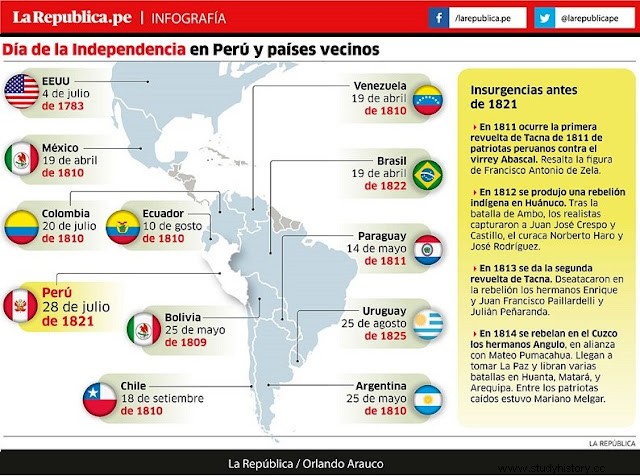

Peru is, in effect, virtually the only country in Latin America that commemorates its independence on the day it was proclaimed and not the day on which (it is assumed) this process began. Therefore, Peru will also be the last Latin American country to commemorate the bicentennial of its independence. The other countries chose to celebrate their independence by recalling insurgent events that mark the beginning of a political revolution, such as the formation of governing boards that disregarded the Spanish authorities in the colonies in the context of the political crisis caused by the invasion of Spanish troops. Napoleon Bonaparte in the Iberian Peninsula between 1808 and 1814. Mexico, for example, obtained its independence, like Peru, in 1821, but celebrates it on the day that the priest Manuel Hidalgo launched a massive popular insurgency in 1810. For this reason Mexico will not wait for 2021 for its bicentennial, it celebrated it in 2010. Chile proclaimed its independence at the battle of Maipú in 1818, but it has also already celebrated its bicentennial because it commemorates its 1810 governing board as its independence day. The United Provinces of South America, as the future Argentina was called, proclaimed their independence in 1816, but Argentina celebrates the May 1810 revolution in Buenos Aires as its independence day and therefore celebrated its bicentennial in 2010. Bolivia and Ecuador did so even earlier, in 2009, because they commemorate their 1809 insurgent meetings in the audiences in Quito and La Paz, respectively, as their patriotic anniversaries.

Peru did not lack insurgencies and anti-Spanish meetings before the arrival of San Martín, analogous to those that other American countries chose to celebrate their independence. There were in Tacna in 1811 and 1813, in Huánuco in 1812 and especially in Cuzco between 1814 and 1815. Here, the revolution led by the brothers Mariano, José and Vicente Angulo and the cacique Mateo Pumacahua was so vast that it reached as far as La Paz. , and had an even more marked separatist content than the Hidalgo rebellion of 1810, which Mexico considers the beginning of its independence process. The Cuzco rebels established a revolutionary calendar that declared 1814 as "the first year of freedom", which was evoked by the populations of southern Peru until well into the republic. But the official memory of the country left these events on the margins, if it even considered them.

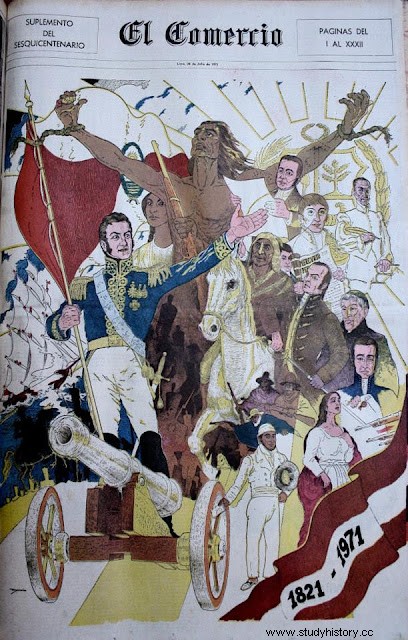

The Trade of 1971, for the sesquicentennial. It is therefore not unreasonable to suppose that the setting of July 28 as the central milestone of independence was a way to avoid referring to the aforementioned regional insurgencies, with a strong indigenous component. And in this the official “creole” history is more similar to the supposedly anti-establishment Marxist historiography of the 1970s than it would like to admit. Both minimize the participation of Peruvians in the independence process, which they conceive as coming from outside, and both see the Indians as manipulated masses. But the San Martinocentric version of independence, far from being fortuitous, was carefully outlined in the mid-nineteenth century by the historian Mariano Felipe Paz Soldán, whose Historia del Perú Independiente (1868) assumes that Peruvian independence literally began in 1819, with the preparations for the expedition of San Martín in Río de la Plata. This version of independence was immediately refuted by the liberal and independence veteran Francisco Javier Mariátegui, and in the 20th century by the historian José de la Riva Agüero. But this did not stop it from being the “official version” and hegemonic.

The Trade of 1971, for the sesquicentennial. It is therefore not unreasonable to suppose that the setting of July 28 as the central milestone of independence was a way to avoid referring to the aforementioned regional insurgencies, with a strong indigenous component. And in this the official “creole” history is more similar to the supposedly anti-establishment Marxist historiography of the 1970s than it would like to admit. Both minimize the participation of Peruvians in the independence process, which they conceive as coming from outside, and both see the Indians as manipulated masses. But the San Martinocentric version of independence, far from being fortuitous, was carefully outlined in the mid-nineteenth century by the historian Mariano Felipe Paz Soldán, whose Historia del Perú Independiente (1868) assumes that Peruvian independence literally began in 1819, with the preparations for the expedition of San Martín in Río de la Plata. This version of independence was immediately refuted by the liberal and independence veteran Francisco Javier Mariátegui, and in the 20th century by the historian José de la Riva Agüero. But this did not stop it from being the “official version” and hegemonic.This long official history was destabilized for the first time when the leftist military government of Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1975) proclaimed Túpac Amaru II as the initiator , with its rebellion of 1780, of an independence that culminated in the fields of Ayacucho, forty-four years later. Velasco thus displaced San Martín from the center for the first time to privilege an indigenous hero. However, Velasco was not creating a new history, so much as making official a memory of independence that had existed on the margins, parallel to and prior to the San Martinian history of Paz Soldán, and whose origins date back to Cuzco journalism in the 1830s. , although space does not allow me to expand on it.

And although the Velasquist version of independence may sound heretical today and even too “radical” for the sensibilities of neoliberal Peru, it was endorsed, no less than by the oldest newspaper and important in the country, before being expropriated by Velasco. The cover that El Comercio de los Miró Quesada dedicates to the sesquicentennial of independence shows in the center a huge Túpac Amaru with a naked torso surrounded by smaller characters, including San Martín. An unthinkable cover today, without a doubt, but that invites us to think, along with everything I have expressed up to here, that independence is not a finished story and that the memory of what it constitutes and means, and how it should be represented, even at an official level, far from being static, has been in constant dispute.

It has been a memory shaped by the events and tensions of each era, and it still is today.

Cecilia Méndez PUCP historian and professor