Some events of our past that are not necessarily real or that did not happen as we were told. Sometimes in history not everything is what it seems (or seemed). Many events or certain theories of the past begin to change after the discovery of new documentary sources or the product of contemporary investigations or interpretations. In other cases, the myths are so well elaborated that they pass for true. Recently, the linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino demonstrated that Quechua did not originate in Cusco nor was it the original language of the Incas, as was thought until now, but that they actually spoke a highland language —already extinct— known as puquina , and who adopted the simi runa in later stages.

Ethnohistory has come to change many ideas about pre-Hispanic Peru. That hypothesis that there were 13 or 14 Incas who ruled the Tahuantinsuyo was not as accurate as it seemed. Since the 1960s, researchers such as María Rostworowski, Franklin Pease, and Tom Zuidema have shown that there was a marked duality in Andean society, not only religiously and socially, but also politically. For this reason, they did not rule out that a correinado could have existed at many moments in Inca history. Even more so —that is what Zuidema believed—, the names that they taught us at school such as Manco Cápac, Sinchi Roca, Lloque Yupanqui, etc. they did not refer to people of flesh and blood, but to dynasties or totems that represented families of the royal ayllu.

—Independence occurred on July 28, 1821?— The debate has been intense since the 1970s. It is evident that on that date José de San Martín pronounced in the Plaza Mayor of Lima the famous proclamation:"Peru is from this moment free and independent...", but the truth is that this was only one of the many declarations that were made in our territory at that time. Our independence, in reality, did not occur in 1821, but was a whole process that began —although there is no chronological agreement among historians— in the last third of the 18th century with the indigenous rebellions, and had local episodes such as the rebellions in Tacna in 1811, in Huánuco in 1812 and in Cusco in 1814 and 1815. This phase ended with the battles of Junín and Ayacucho in 1824, although not until 1826 the last royalist fort, Real Felipe, surrendered.

One of the most iconic paintings of the war with Chile:Alfonso Ugarte jumping from the nose. However, there is no evidence that the hero jumped.

One of the most iconic paintings of the war with Chile:Alfonso Ugarte jumping from the nose. However, there is no evidence that the hero jumped. “What happened on July 28 was just a symbolic act,” says historian Claudia Rosas, co-editor of the book El Perú en Revolución, which reconstructs this era of wars and revolutions. "In 1821 many regions were still under Spanish power -he adds- and we must not forget that after the arrival of San Martín in Lima, Viceroy La Serna moved to Cusco and from there he continued fighting against the independence armies". we have in mind the solemn painting by Juan Lepiani, in which San Martín is seen before a jubilant crowd, the truth is that this event was not so tremendous. In addition, the first proclamations did not take place in the capital, but in the north of the country, in the immense administration of Trujillo, which included cities such as Piura, Trujillo, Cajamarca and Maynas, between December 1820 and January 1821, as explained by the historian Elizabeth Hernández in the aforementioned publication.

—Did our flag emerge from a dream of San Martín?— Over time, some fictions have passed for certain, perhaps because they contain such suggestive images that it is difficult or even painful to deny them. And it is idyllic to believe that our rojiblanca was devised by San Martín from a dream he had in the bay of Paracas, fanned by the shade of a palm tree. The truth is that this never happened in reality, but it is just a beautiful story by Abraham Valdelomar. In the story, the Liberator dreamed — ironies of the present — of “a great country, orderly, free, industrious and patriotic”, over which a beautiful flag was raised. When he opened his eyes, a flock of parihuanas, white-breasted and red-winged, flew across the blue sky. San Martín thought no more and told his generals that this was going to be the flag of Peru.

As Fred Rohner explained in his entertaining book Secret History of Peru —the second volume has just appeared—, this story is required reading in schools and most teachers - in good faith - have avoided saying that it is a literary invention. The truth is much simpler. The first San Martinian flag (the one with the red and white colors in diagonal stripes) was the adaptation of a colonial emblem very widespread in the Viceroyalty called the Cross of Burgundy, which was adapted for the campaigns in Peru.

—Was Simón Bolívar the cause of the dismemberment of our territory?— One of the historical accusations made against the Venezuelan liberator is that of being responsible for the mutilation of our territory due to his political and personal appetites. This is not entirely true. Before the arrival of Simón Bolívar in Peru —in September 1823— the independence process was at a standstill. Bolívar, with the army of Gran Colombia, revitalized the war against the fidelistas and royalists, and put an end to Spanish domination. The other side of the coin is that over 36 months he became the dictator of Peru, and made and unmade our fledgling republic. He not only drafted constitutions tailored to him and persecuted his opponents to death, but also consolidated the separation of Upper Peru.

Painting by Lepiani titled “The Answer”. But was the cause of this dismemberment? Historian Natalia Sobrevilla says no. "The truth is that these territories were already autonomous since 1809, when the governing boards of Quito, in the north, and of La Paz and Chuquisaca (now Sucre), in Bolivia, were created," he explains. Since that time, these boards they were already seeking to be autonomous from Lima and also from the viceroyalties of New Granada (which after independence became Gran Colombia) and the Río de la Plata, whose capital was Buenos Aires. “Blaming Bolívar for these events is a historical exaggeration” , adds the researcher.

Painting by Lepiani titled “The Answer”. But was the cause of this dismemberment? Historian Natalia Sobrevilla says no. "The truth is that these territories were already autonomous since 1809, when the governing boards of Quito, in the north, and of La Paz and Chuquisaca (now Sucre), in Bolivia, were created," he explains. Since that time, these boards they were already seeking to be autonomous from Lima and also from the viceroyalties of New Granada (which after independence became Gran Colombia) and the Río de la Plata, whose capital was Buenos Aires. “Blaming Bolívar for these events is a historical exaggeration” , adds the researcher.—Was Ramón Castilla a liberal who abolished slavery?— From the beginning of 1854, Ramón Castilla was involved in a civil war with the government of José Rufino Echenique, who in a fit of populism offered freedom to all the slaves who enrolled in his army. Then, Castilla, who had been appointed provisional president, went further:on December 3, 1854, he announced the unconditional abolition of slavery in Huancayo. But at some point he was about to back down and this newspaper waged an editorial campaign to make him keep his word. It is said that around three thousand enslaved people joined the Castilian army and managed to defeat the troops of Echenique. “He was not a liberator out of conviction but out of interest”, says Natalia Sobrevilla. “Moreover, during his first government he had allowed the importation of slaves from New Granada. He had no intention of granting freedom until the civil war with Echenique ”.

The decree of manumission was also given at a time when the winds were already blowing in another direction in the world. In the mid-nineteenth century, the slave trade was condemned by more and more countries, and this system was a burden for the nascent capitalism that emerged after the industrial revolution. In the Peruvian case, there was an additional fact:the boom in guano wealth allowed the State to have enough resources to pay the owners for each freed slave. This good fiscal economy also facilitated the abolition of the indigenous tribute that Castile made in July 1854.

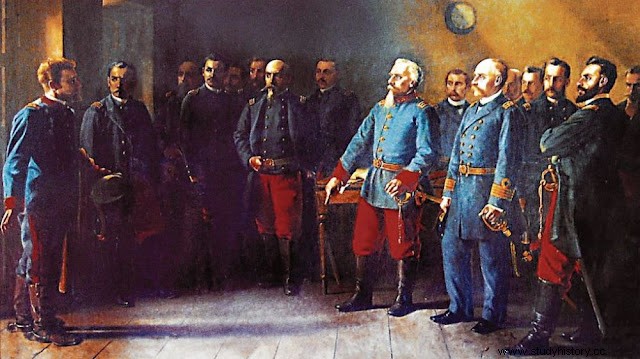

—Is the photograph of Bolognesi and his staff in Arica true? The story is well known:the Chilean forces sent an emissary, Major Juan de la Cruz Salvo, to ask for the surrender of the Peruvian troops in Arica; Faced with this, the head of the Peruvian garrison, Francisco Bolognesi, replied that “he would fight until the last cartridge was burned” . There is a painting by Juan Lepiani that portrays the scene known as “The Answer” , in which the old military man is seen with his staff. The surprising thing is that in the 1990s —more than a hundred years later— a photograph began to circulate in which Bolognesi and the Arica commanders were seen at that historic moment. The image was found in Tacna and offered to this newspaper, but its authenticity was questioned. It is said that Genaro Delgado Parker acquired it later and had it restored at the Kodak studios in the United States, where they assured him that it belonged to the 19th century, and that it was not a montage.

However, the doubt persists among specialists, such as the Argentine historian Julio Luqui-Lagleyze:some details —buttons, boots, swords— do not correspond to those used by Peruvians in Arica, and as the historian Sobrevilla infers, it would be more of a photo of a theatrical performance made towards the end of the 1890s.

The alleged photograph of the moment portrayed in the painting, which began to circulate in the 1990s. suspects that it is a theatrical performance. A specialist in photography of the Pacific War, Renzo Babilonia, maintains that, without entering into controversy, the image is suspicious. Especially since the faces of those portrayed do not resemble the photographs of the time taken by Courret or those of Lepiani's painting, who was very realistic when painting his characters. “But, in favor of a supposed authenticity of the photo —says Babilonia—, I can tell you that at the time of the war there was a photographic studio in Arica, the Rodrigo. Many of the combatants took photos there.”

The alleged photograph of the moment portrayed in the painting, which began to circulate in the 1990s. suspects that it is a theatrical performance. A specialist in photography of the Pacific War, Renzo Babilonia, maintains that, without entering into controversy, the image is suspicious. Especially since the faces of those portrayed do not resemble the photographs of the time taken by Courret or those of Lepiani's painting, who was very realistic when painting his characters. “But, in favor of a supposed authenticity of the photo —says Babilonia—, I can tell you that at the time of the war there was a photographic studio in Arica, the Rodrigo. Many of the combatants took photos there.”—Did an Aprista militant kill Sánchez Cerro?— For some, uncomfortable; for others, unbearable. That was, for a strong sector of the country, the situation of President Luis M. Sánchez Cerro on the morning of Sunday, April 30, 1932, when a young man of APRA affiliation, Abelardo Mendoza Leyva, pulled the trigger of his Browning and committed the last assassination of our republican history. The setting was the Santa Beatriz racetrack, where the then president had finished reviewing some 30,000 troops willing to go to the border with Colombia and recover Leticia.

The last stretch of Sánchez Cerro's political life was stormy . He had overthrown Leguía and, in 1931, leading the Revolutionary Union (a party with great popular roots), he defeated Haya de la Torre, head of the other mass movement, APRA. A polarized country saw how Haya's supporters denounced electoral fraud. Political violence broke out, a virtual civil war that had its most dramatic point in the Aprista Revolution of Trujillo, in 1932. The responsibility of the Aprista leadership for the assassination could never be proven. Precisely, the book How to kill a president has just appeared. , by Rolando Rojas, detailing the details of the assassination of Sánchez Cerro and the subsequent investigations that, although they concluded that it was a plot, could not find culprits beyond Mendoza Leyva himself. 19 suspects were arrested, most of them humble people linked to APRA militancy, who were subjected to interrogations that did not lead to anything. However, the final report was clear:“The ballistics expert stated that there were at least four people who fired on the president's car:“It is impossible for one or two people to shoot from behind, forward and from above”, specifies the document.

Who or who shot Sánchez Cerro? One of our historical mysteries. What is evident is that the fear that Sánchez Cerro could articulate a party that would be more successful with the masses pushed the murderer, or those who instigated him, to crime. The oligarchy, for its part, no longer saw Sánchez Cerro as a guarantor of order, but rather incapable of controlling APRA and determined to push the country into international conflict. There was talk of the complicity of the United States, suspicious that the issue of Leticia, already settled in favor of Colombia, would be removed. Basadre himself left the case open with these words:“If the presidential car was the target of eight shots fired by various hands, that is, if there was a plot as peremptorily stated in the ruling, there is no way to find proof today”. [Juan Luis Orrego]

Who or who shot Sánchez Cerro? One of our historical mysteries. What is evident is that the fear that Sánchez Cerro could articulate a party that would be more successful with the masses pushed the murderer, or those who instigated him, to crime. The oligarchy, for its part, no longer saw Sánchez Cerro as a guarantor of order, but rather incapable of controlling APRA and determined to push the country into international conflict. There was talk of the complicity of the United States, suspicious that the issue of Leticia, already settled in favor of Colombia, would be removed. Basadre himself left the case open with these words:“If the presidential car was the target of eight shots fired by various hands, that is, if there was a plot as peremptorily stated in the ruling, there is no way to find proof today”. [Juan Luis Orrego] FOUR MYTHS OF THE PACIFIC WAR

The death of Francisco Bolognesi There is a version that Francisco Bolognesi and a few survivors, when the battle of Arica was almost over, on June 7, 1880, surrendered on the hill raising a white flag, considering that they had given everything for the defense of the homeland. However, the correspondent of the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio published the following two days after the battle:“Only More and Bolognesi continued to fire with their revolver until a soldier instantly killed him with a bullet that went through his skull.” This testimony, similar to that of Roque Sáenz Peña, would show that Bolognesi died fighting.

Bolivia abandoned us It is true that after the allied defeat in Tacna, on May 26, 1880, the remains of the Bolivian army returned to their country and did not enter into combat any more. What is not contemplated is that said battle practically finished with said army. Since then, Narciso Campero -president of Bolivia- moved to Oruro to form a new one. Meanwhile, Bolivia continued to support Peru with weapons and economic resources. Moreover, during 1882-1883, Chilean Foreign Minister Luis Aldunate wrote to his Bolivian counterpart Antonio Quijarro up to five times to offer him Tacna and Arica in exchange for going over to the Chilean side. Bolivia always rejected these offers and maintained its alliance with Peru.

The death of Alfonso Ugarte Alfonso Ugarte was among the group of officers who resisted relentlessly at the Arica hill until the end of the battle. The jump from him to death on the nose, mounted on his white horse and brandishing the national flag, is, in narrative terms, very typical of literary romanticism that has notably influenced the epic-historical accounts of nations. Alfonso Ugarte did die on the hill and part of his remains were recovered at the foot of it and buried in the Arica cemetery. According to the historian Rubén Vargas Ugarte, in 1890, his remains were exhumed to be repatriated. These also have the death certificate signed by the vicar of Arica José Diego Chávez, and today they rest in the Crypt of the Heroes of the Presbítero Maestro cemetery, along with those of Grau, Bolognesi and Cáceres.

Arequipa surrendered without firing a bullet On October 28, 1883, the Chilean army entered Arequipa without encountering resistance, but the reasons for this situation are complex. The headquarters of the Peruvian government of Lizardo Montero was installed there, who, given the proximity of the Chilean forces, agreed with Narciso Campero to withdraw the national forces to Puno, to join the Bolivian forces there and continue the resistance. Montero made the mistake of endorsing in the town the withdrawal of the army from Arequipa to Puno. This motivated an uprising of the citizens who were mostly inclined to give battle. In the riot the army dispersed, Montero managed to escape from the mob by a ravine, and Mayor Diego Butrón was assassinated for supporting the withdrawal plan. After these events, with the city headless and unarmed, the “peaceful” occupation of Arequipa took place.

[Daniel Parodi, professor at UL and PUCP]