So where does the name Peru come from? His story, which we are going to try to summarize here, has to do, first of all, with a rumour, then with a disgraced warrior leader and finally with a conqueror who scratched glory but on whom fortune did not smile.

The rumors

This story begins in 1513. For Europeans, America was the great novelty but also the great unknown. The Caribbean had already revealed its islands and the conquerors had barely combed the coasts of Central America and northern South America. They did not know if it was a large or small continent and the maps, with many errors, were just beginning to be made. This detail is important for what we want to tell. Look at the following image:On the left there is a map drawn precisely in 1513. Next to it there is a current map. Notice that the Europeans had no idea of the shape of America. There is a large sign that reads "Terra incognita", that is, unknown land. Nobody knew that on the other side was the Pacific Ocean. Mexico had not yet been explored, much less Peru. But this "terra incognita" was already given names. The most common was "Tierra Firme". There, on the shores of the Caribbean, on the current border between Panama and Colombia, was where the Spanish founded their first permanent settlement:Santa María de la Antigua. The day to day in that "city" was difficult. The Spaniards were not used to the rigors of the tropical climate (it is one of the most humid regions on the planet) and half of the newcomers fell ill and died as a result of strange diseases. To make matters worse, the natives were hostile... although of course they had plenty of reasons to be, because the European invaders were fond of looting their villages, testing them with their strange and powerful weapons and even launching the famous "dogs of war" at them. ". One day in 1513, a band of Spanish explorers was pillaging a native town north of Santa Maria. There were a few pieces of gold in the loot and that caused some fights between the conquerors. It was then that the son of the village leader, Panquiaco, told them the following:

"If you want gold so much , I will show you a region where you can fulfill your desire; but you are very few and you will need to be more, because you will have to fight against great kings who defend their lands with great effort and rigor"

Panquiaco explained to them that in order to go to that region they had to first reach a sea "where other people navigate with sailboats and oars."

Another sea?, the Spaniards asked themselves, which until then they had seen no other sea in the New World than the Caribbean. The leader of the squad, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, followed the instructions given by the natives and, after several days of walking and climbing a mountain range of dense vegetation, he spotted the promised sea. As far as is known, they were the first Europeans to see the Pacific Ocean. A relevant detail in this story is that Balboa's group included an experienced soldier named Francisco Pizarro.

Some months later, while exploring the "new sea" coastline, Balboa heard from another cacique that following the line from the coast to the south "there was a large quantity of gold and certain animals on which the people put their loads". Chief Tumaco made a figure with clay to show them what those animals looked like. It was the first representation of a llama that the conquerors saw. Of course there were no llamas in Panama, so historians assume that Tumaco and its people must have known them from the merchants who came on sailboats (from Ecuador, Tumbes or even from the Peruvian region of Chincha) to exchange products with the Central Americans. . Archeology has found much evidence of these exchanges. Balboa's desire to continue exploring and conquering the mysterious country to the south was kindled, but his own political problems with the colonial authorities interrupted his search... and his life (he was put on trial and beheaded).

The Legendary Warrior

But his discovery had many fruits:A year later the enthusiasm of the Spanish to explore the region had multiplied, although it was very difficult to walk through the jungle, especially the one further south, which until today It is known as "The Darién Gap". It is so impenetrable and hostile that even in our century it has not been possible to build a road that crosses it (El Darién is, precisely, the only missing section of the Pan-American Highway).

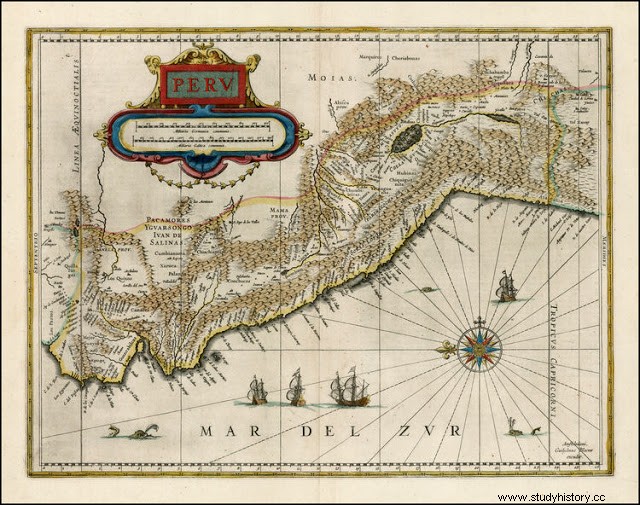

1635 map showing the coastline of what was then considered Peru (north is to the left). It included the current republics of Ecuador and Bolivia. It was made by the Dutchman Willem Bleau. In one of these explorations, Captain Francisco Becerra received a new piece of the puzzle of the name of Peru:The natives told him about a warrior chief named Birú, very powerful and feared, who ruled a province of the same name. Becerra advanced in search of the cacique but was discouraged by the swamps, the clouds of mosquitoes and the labyrinths of vegetation. After looting some indigenous villages and obtaining a great deal of loot, he turned around and returned to Santa María de la Antigua.

1635 map showing the coastline of what was then considered Peru (north is to the left). It included the current republics of Ecuador and Bolivia. It was made by the Dutchman Willem Bleau. In one of these explorations, Captain Francisco Becerra received a new piece of the puzzle of the name of Peru:The natives told him about a warrior chief named Birú, very powerful and feared, who ruled a province of the same name. Becerra advanced in search of the cacique but was discouraged by the swamps, the clouds of mosquitoes and the labyrinths of vegetation. After looting some indigenous villages and obtaining a great deal of loot, he turned around and returned to Santa María de la Antigua.On the way back he came across another expedition, led by Captain Gaspar de Morales, who told about that matter of the Biru. Morales took the post and spent a short time in the south of what is now the Republic of Panama, undergoing various adventures, including an alleged invasion of the lands of Birú. The chronicle of Bartolomé de Las Casas (who narrates this expedition) is not very explicit about the geographical location of that town, but current historians do not believe that it was that of the true cacique Birú. There was a battle without a winner and Morales turned around to return to Santa María, with his troops almost destroyed. It became clear to the residents of the city that looking for the mysterious cacique was getting into unnecessary trouble.

The curiosity of the Basque

Some years passed and no more was heard of the elusive cacique. More important matters now occupied the attention of the Spanish colonists:They abandoned the city of Santa Maria de la Antigua, on the shores of the Caribbean, to found a new city, Panama, on the shores of the newly "discovered" Pacific. From there they sent expeditions to the north, where the jungles were less cruel than those in the south and where looting brought good profits. It is in this context that, in 1523, a Basque named Pascual de Andagoya entered our history. The governor of Panama asked him to visit, on a mission of peace, the Indian allies of the Spanish who lived south of the new city because Andagoya had a rare ability to understand the natives. When he arrived at the town of Chochama, he noticed that the Indians did not want to sail because, they said, it was the season in which the canoes of a certain "Cacique Birú" passed by to attack the town. Again the happy name! Could it be a coincidence? Andagoya, like all the settlers of Tierra Firme, knew very well the legends about this Birú and the failure of those who previously wanted to find him. But he decided to try his luck using a different strategy:Go along the beach, as far south as possible, to avoid getting lost in the jungle. And so, taking advantage of the fact that he was on good terms with the Chochameños, he improvised an expedition with his soldiers and with men from Chochama, to go and find out, once and for all, if that Biru existed or not.

The expedition advanced south for a week, without incident. Two small ships escorted them by sea. Until then, no European had traveled through these regions. Then they came to the mouth of a river that, as far as he could tell, led to the heart of the Biru lands. And he found it. He was not a legend but a flesh and blood character, a kind of Lord of War, who ruled over several towns in what is now the province of Chocó in Colombia. There were battles and even a siege of a small fortress, but finally the Spanish weapons and his battle tactics, unknown to the natives, gave Andagoya victory. He found some gold and tried to deal with the war chief, whom he had captured.

The chief (who supposedly befriended him) told him that, beyond, where the jungles end and great mountains rise, there was a country full of treasures ruled by a very powerful king. The conqueror must have said something like "well, we're here, let's continue" and put together a new expedition with his soldiers, the Chochameños and the men of Birú with the intention of "discovering" the fabulous kingdom of the south, the same one that Balboa dreamed of. to conquer.

Failure

The kingdom they told him about was not a myth. Back in the Central Andes, a man ruled, Huayna Cápac, who was the most powerful monarch that ever existed in Pre-Columbian America. The Inca extended his power from the central region of Chile and northwestern Argentina to the Sierra de Pasto, in Colombia. But the lands of Chief Birú were very far from the Inca dominions and separated from them by those rainy forests that were not to the liking of the Children of the Sun. So how did Birú know about the Incas? Thanks to the commercial communication that existed between both geographical areas. Crossing the South American Pacific, merchants had been exchanging products for at least twenty centuries. For example, textiles from the Central Andes were highly valued in the north. And the shells of various molluscs (spondylus, strombus) from the tropical seas were used by the ancient Peruvians for their religious rituals.

Andagoya, Cacique Birú and the others, reached the San Juan River (Colombia). The conqueror personally toured the wide delta of the river in detail, looking for a place that would be suitable to serve as a port for deep-draft ships. And it is that the Basque was thinking big:he was aware that he was very far from Panama and if his adventure was successful he would need to find a place so that ships with more people and resources could come to help him. But then he had an accident with some rocks, hit himself, fell out of the canoe he was in and, dragged down by the weight of his armor, nearly drowned. There he would have finished his story if the very cacique Birú had not saved his life. After spending several hours perched on the canoe, beaten and soaked, while waiting for them to come pick them up, Andagoya fell ill and his men decided to abort the mission and return to Panama.

The name

Despite his failure, Andagoya arrived in Panama with an incredible story, a certain amount of gold and an unexpected companion:the legendary Cacique Birú in person. The Spanish laws stipulated that the conqueror could keep his booty but after paying the corresponding tax:The royal fifth, that is, 20% of everything he had "earned". During the procedure, carried out at the Foundry House of Panama, a document was drawn up that gave an account of the treasure and that is very important for our history. This document says the following:

"In the said city of Panama, in the said Casting House, on the 23rd of July 1523, in the presence of the said officials, they brought to manifest, Pascual de Andagoya, who went to the province of Peru, and Juan García Montenegro, who went by Inspector, certain gold that they said had been the said trip from Peru"It is the first time in history that the word Peru was written to refer to a place, "a province". This shows that already in 1523 the region where Andagoya was was called Peru, but where did that name come from? The closest word we have seen so far is the name of the cacique. Does it have something to do with it? Of course. The explanation can be found in a later text by Father Las Casas (1549):

"And by this name Birú, they said they called the Spaniards later to the land of Peru, changing the letter "b" into the "p" letter"And Pascual de Andagoya himself explains the matter in his chronicle:

"I discovered, conquered and pacified a great province of Lords that called Peru, where all the land before it took its name"And indeed, since then, everything south of Panama was called Peru. We could almost say that, for a few years, that word, which was nothing more than the mispronounced name of a Colombian cacique, was the name of an entire continent to explore. A good synonym for "terra incognita".

Ancient Peruvians and Ecuadorians sailed rafts with sails along the Pacific coast to exchange products with other regions, from Chile to northern Colombia. It was thanks to what those merchants trafficked that the Spanish conquerors knew of the existence of the Inca Empire. In the image, a raft from Guayaquil as seen by the Spanish travelers Ulloa and Juan in the 18th century. Although two centuries had passed since the conquest, the appearance of these ships was the same as that described by the conquerors. Only the flag seems to be a "modern" element. (Image:Wikimedia Commons) The size of Peru

Ancient Peruvians and Ecuadorians sailed rafts with sails along the Pacific coast to exchange products with other regions, from Chile to northern Colombia. It was thanks to what those merchants trafficked that the Spanish conquerors knew of the existence of the Inca Empire. In the image, a raft from Guayaquil as seen by the Spanish travelers Ulloa and Juan in the 18th century. Although two centuries had passed since the conquest, the appearance of these ships was the same as that described by the conquerors. Only the flag seems to be a "modern" element. (Image:Wikimedia Commons) The size of Peru Andagoya was not in a position to ride a horse again and, therefore, to attempt a new adventure, so the "position" of conqueror of Peru was left vacant. The residents of Panama commented on his trip as a curiosity, but they were more interested in what was happening to the north, that is, in the conquest of Nicaragua, a safer and more lucrative enterprise than the exploration of the southern lands. It was then that a veteran who had served with Balboa the day Panquiaco told them about the new sea saw the circle close in front of him. Naturally we are talking about Francisco Pizarro who, a year after Andagoya's return, decided to organize the conquest of the mysterious southern country. We are not going to recount here his adventures which, as we all know, definitively eclipsed the history of the Basque. We will only say that in the course of the following years Pizarro would make three trips to the south, he would be appointed Governor of Peru, he would run into an empire plunged into civil war, he would capture the successor of Huayna Cápac in the Inca city of Cajamarca and, using of a rare talent for Andean politics, he would make alliances with all the enemies of the people of Cusco (Huancas, Chachapoyas, Cañaris, Tallanes, Huaylas) to seize absolute power in the Central Andes.

He stopped when Pizarro died in 1541 , the "limits", so diffuse and wide of the Peru that Andagoya "discovered", had been redefined. The Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de León explained that in the mid-sixteenth century, what was known as "Peru" ranged from Quito (Ecuador) to the town of Plata (the current city of Sucre, in Bolivia). But it did not include the land that Andagoya had visited. That is to say, the Peru of Andagoya was left out of the historical Peru.

The fate of the namers

And what happened to him and Birú? About the latter we only know that he was taken to Panama to declare himself a vassal of the King of Spain. But we do not know if he returned to his land, if he stayed in Central America or if he had a long life or not. Unfortunately, the fate of the vanquished is written by the victors, always in a dubious manner and on the margins of history.

As for Andagoya, after a long convalescence, he recovered from his wounds and had other raids in Central America, even becoming mayor of Panama, where he wrote a chronicle about his adventure with chief Birú. But it must not have been easy for him to see with his own eyes the shipments of treasures that arrived in the city from the country of the Incas. He must also have heard all kinds of incredible stories, about the cobbled roads that crossed the Peruvian mountains and their palaces upholstered with gold plates. But he got over it and went back to his old ways. He returned to the Colombian zone that he had discovered and to the same San Juan River where he had once fallen looking for a natural harbor. This time he found it and made it a city. Until today it exists and is called Buenaventura. But his enthusiasm won him over, he wanted to conquer more territories and soon found himself involved in a boundary conflict with another Spaniard (Benalcázar, one of Pizarro's men who, from Quito, was conquering southern Colombia) and although he got away with it these problems, he had to travel to Spain to give explanations. Once in his homeland, he found a new excuse to go to Peru, but this time to the real one.

And the news that reached the Spanish court spoke of the insurrections of Pizarro's successors and even of his wishes to gain independence from Spain. The crown reacted energetically by organizing a military expedition under the command of Pedro de La Gasca to punish the rebels. Our character enlisted with the peacekeepers and marched to Peru as captain of La Gasca. That was how, with more than two decades of delay, the Basque followed in the footsteps of Pizarro, landing in Tumbes, getting to know Cajamarca (where the Inca had fallen) and traveling those great cobbled roads that he had heard about. He finally arrived in Cusco and was able to see the famous stone temples, already half in ruins and without their golden plates, where he had a clear idea of what had been lost. But, although late, he had arrived and his mission, this time, was a success:the rebels were defeated. What would have gone through the mind of the conqueror at that moment? He perhaps felt reconciled to his fate and ready to reclaim some of the glory that 25 years ago he had relinquished. We will never know because he never wrote about this stage of his life. The little information available indicates that after completing some missions in Upper Peru (Bolivia) and returning to Cusco, his health, once again, ruined his projects. In the year 1548, old wounds intensified and ended with the time of Pascual de Andagoya, in the center of the country that today owes his name.

Sources

The first historian who deals seriously with this issue is Raúl Porras Barrenechea. He "cleans" the panorama, eliminating a multitude of speculations that chroniclers and scholars have made since the 16th century on the name of Peru. Porras dismisses, with forceful arguments, the suggestions that "Peru" derived from some Caribbean or Antillean word, or from Quechua (as the chronicler Blas Valera suggested), or from some biblical word (such as that of the legendary city "Ofir" as assured the chronicler Fernando de Montesinos); dismisses the old debate about a river Birú (which chroniclers such as Oviedo and Garcilaso defended but Cieza ruled out) or the versions that suggested that the name derives from the Mochica valley of Virú, known by the Spanish long after the word was used by them . It is Porras who demonstrates that the key to the matter is Pascual de Andagoya, although he warns that Pascual exaggerates his actions in his chronicle. Regarding the findings of this great historian, we recommend the following summary of his famous work "The Name of Peru", published online by the Research Institute that bears his name (Click here) http://www.institutoraulporras.org/el- name-of-peru/

But Porras did not have all the information. He was unaware of a document that was discovered by the historian Miguel Marticorena Estrada in the Archivo General de Indias (the document that we have mentioned in this article) and that was published in the text "El Vasco Pascual de Andagoya, inventor of the name of Peru", in the now defunct magazine Cielo Abierto, in Lima, in 1979. This paper confirms Andagoya's "denominator" role. One of the best contemporary compilers of the information presented here was the historian José Antonio del Busto. who reconstructs the Andagoya itinerary and does his own cleaning of what is plausible and what is not in the reports about chief Birú. He did it in volume II of "Maritime History of Peru", from the perspective of the name of our country in "La Conquista" (Volume III of "General History of Peru", Lima, 1994) and from the perspective of the conqueror of the Peru in his essential work "Pizarro" (Ediciones Copé, Lima, 2000). As for what Andagoya himself wrote, we will mention the name of his chronicle:"The relationship of the events of Pedrarias Dávila in the provinces of Tierra Firme or Castilla del Oro, and what happened in the discovery of the South Sea and the coasts of Peru and Nicaragua". In it he tells everything he knows about the founding of Santa María and Panama, the adventures of Balboa and his own encounter with the cacique Birú. Fray Bartolomé de las Casas compiled part of the stories of Balboa, Andagoya, Becerra and Morales in his monumental Historia de las Indias, completed in 1549. He also mentions the cacique Birú and suggests that Morales met him, without being able to defeat him.

An article by Pablo Ignacio Chacón