By Me. Cláudio Fernandes

The history da read became a very fruitful field of study from the 1970s, especially with the matrix of historiography developed in France that became known as nova history . It was with this “new story”, or new history cultural , which developed an interest in new objects of study, new approaches and new problems for History. One of these new “objects” was exactly the “practice from reading” , that is, as in the various periods of human history, the practice of reading was transformed according to the social construction of each of these periods.

The “new history” approach aimed to abolish the old schemes of historical studies that were tied to schematized and generalizing analyzes of the past that did not offer elements to apprehend the atmosphere of the various situations in which the various human groups found themselves. In order to attempt such an apprehension, it was necessary to channel research into the “history of practices.”

The history of reading practices is closely associated with the history of writing accommodation supports. These supports can be from tablets with writing cuneiform from ancient Mesopotamia until the writing virtual of the monitors from computer , passing through scrolls of papyrus, codices, written in stone, written in leather, among others. These supports determined or, at the limit, contributed decisively to shaping the practice of reading in each specific period. For example, in ancient societies, where writing was a privilege of priests, scribes and other people linked to hierarchical functions, reading was, by definition, an oral and collective practice. It was read aloud to a large number of people. More often than not, various literary texts were learned by heart, as was the case with the education of children in Athens, who memorized and recited excerpts from Homer's epics.

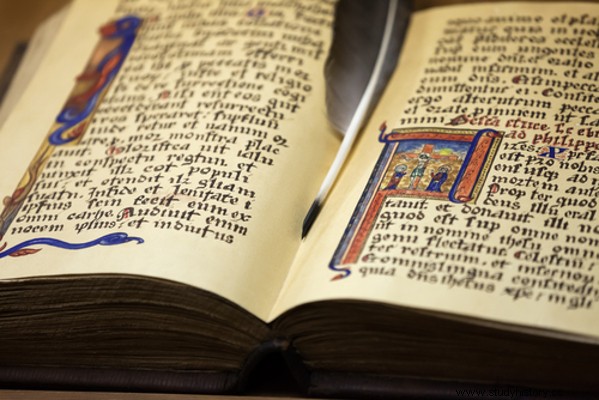

The practice of reading silent , that is, the habit of reading individually and in silence, was only born with the copyist monks in the Middle Ages. And it was born in this specific context and with these social actors because of the circumstances in which they were inserted. The monks who had the duty of copying, that is, replicating manuscripts, whether classical (Greek and Roman) or Christian, and the ornament of the codices (books in which the copy was inserted) with illuminations (illustration art of the codices), needed a silent environment that favored careful reading and precision for work. Since then, this practice of silent reading became secularized, became common, especially after the invention of printing by Gutenberg in the 15th century.

Medieval codex with illuminations

In the 18th century, with the advent of literary romanticism and book fairs in several European cities, the practice of reading became a really popular habit with a great impact on society. . Suffice it to say that the reading of political pamphlets and philosophical writings of the Enlightenment mobilized, to a large extent, the bourgeoisie of France to the revolutionary action of 1789.

One of the main representatives of studies on the history of reading, the historian Roger Chartier , dedicated himself to understanding the impact that reading practices had on what he called “interpretive communities” throughout history. The relationship we have today with reading, for example, is closely associated with the construction of technology-dependent social habits, such as the computer screen and the internet.