In present-day Iran there are numerous ancient inscriptions from the Achaemenid period, for only one outside the country located in the Fortress of Van in Turkey, and commissioned by Xerxes I in the 5th century BC.

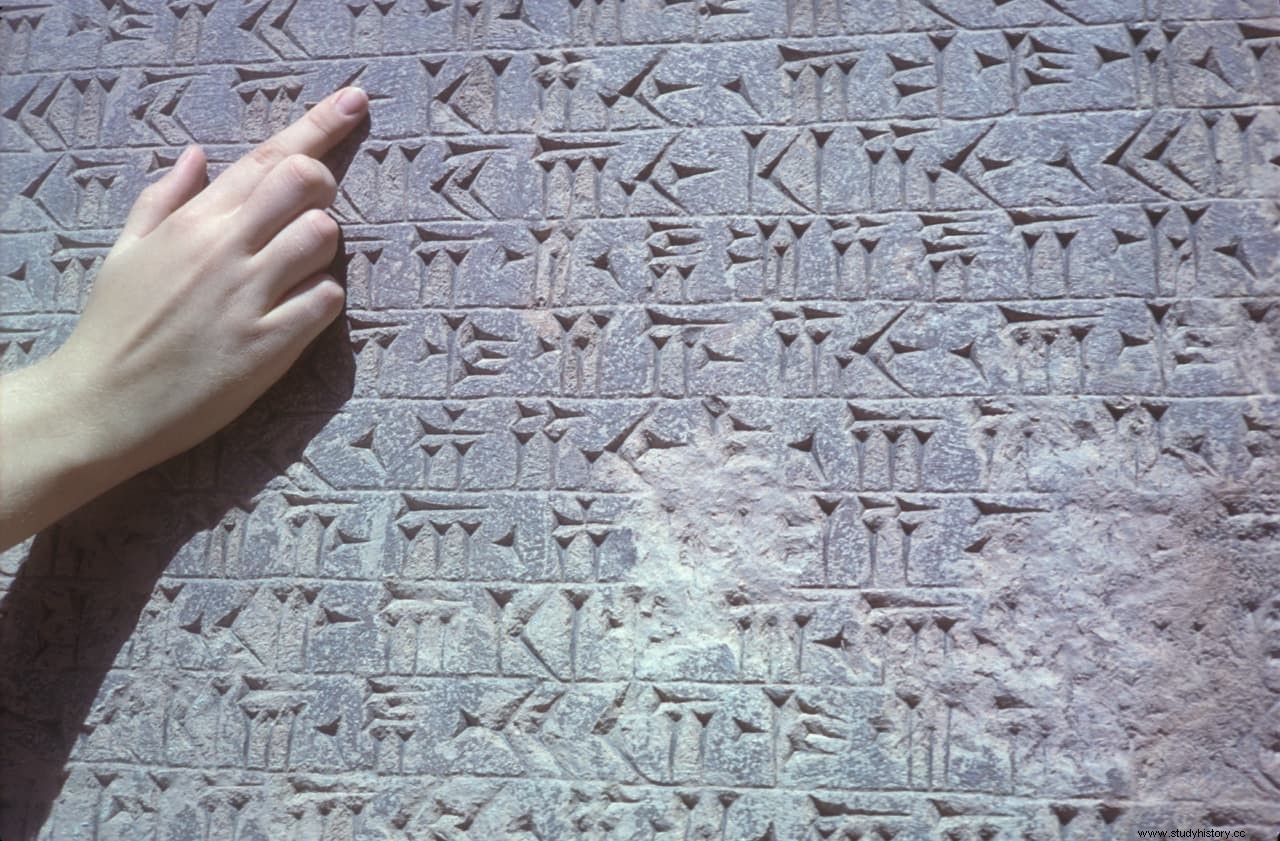

The Persians of the time of Darius I and his son Xerxes I used a type of cuneiform writing, derived from Sumerian-Akkadian but so different that most experts consider it to have been invented around the year 525 BC, precisely to be able to record the exploits of the Achaemenids in the commemorative monuments. Along with this Persian cuneiform script, most inscriptions also include Elamite and Akkadian, languages spoken by the subjects of the empire.

But by the second century AD. this Persian cuneiform semi-alphabet, whose use had been declining and gradually replaced by the Phoenician alphabet, became completely extinct and the knowledge of its reading and interpretation disappeared.

For centuries, travelers to Persepolis gazed at the inscriptions with curiosity and wonder, failing to understand their meaning. It would be necessary to wait until the Arab historians of medieval times made the first decipherment attempts, all of them unsuccessful.

The decipherment of the cuneiform script

In 1474 the Venetian ambassador Giosafat Barbaro traveled to Persepolis to try to convince Uzun Hassan, the emperor of the Ak Koyunlu dynasty, to attack the Ottomans. Barbaro was in Persepolis, to which he wrongly attributed Jewish origin, and was the first European to visit the ruins of Pasargadae, where he heard the legend that the tomb of Cyrus the Great was attributed to the mother of King Solomon. On his return he wrote a chronicle of his travels titled Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia , in which he gave an account of a strange writing that he had found carved on temples and clay tablets.

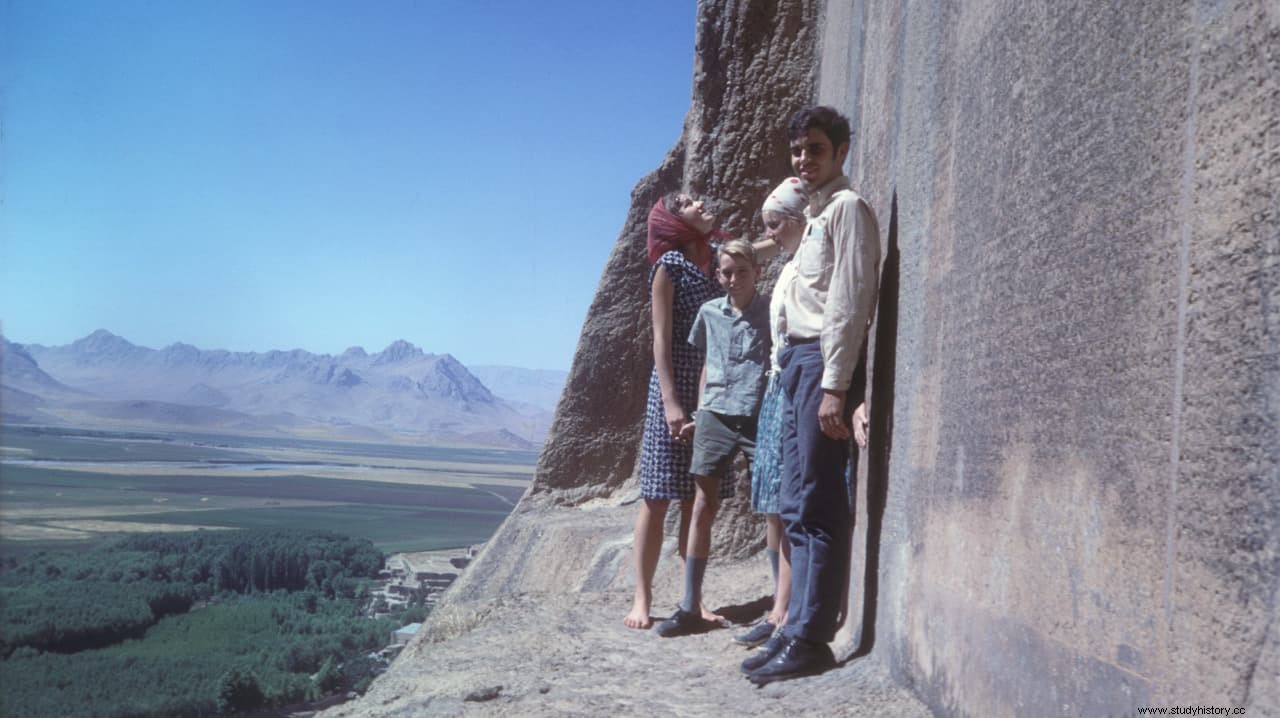

In 1598 the Englishman Robert Shirley accompanied his brother Anthony to Persia. He had been hired by Shah Abbas the Great to modernize and train the army in the likeness of the British. There he saw the Behistun inscription, made at the behest of King Darius I at some point in his reign (522 BC-486 BC). The monumental inscription is located about 100 meters high on the wall of a cliff in the province of Kermanshah, in the west of the country.

But Shirley, unaware of the writing and its meaning, interpreted the figurative reliefs as Christian, as did the other Westerners who visited her successively:the French general Gardanne, Sir Robert Ker Porter, and the Italian explorer Pietro della Valle, who saw in her a representation of Jesus with his apostles or of the tribes of Israel.

In 1627 the historian Thomas Herbert accompanied Dodmore Cotton, who had been appointed ambassador to Persia along with Shirley, with the misfortune that shortly after his arrival both Cotton and Shirley died. Herbert then spent almost a year traveling in Persia, and in 1638 he published a book entitled Some Yeares Travels into Africa &Asia the Great . In it he reported a dozen lines of strange characters…consisting of figures, obelisks, triangles and pyramids that he had seen near Persepolis, indicating that they appeared to him to be Greek.

In the 1677 reissue he reproduced some parts, indicating that they were readable and therefore decipherable. He also pointed out, correctly, that the symbols did not represent letters but words and syllables, and that they should be read from left to right. However, he was not able to find its meaning.

When almost a century later the German explorer and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr made the first complete copies of the Persepolis inscriptions, and they began to spread throughout Europe in 1767, many researchers studied them and were able to decipher some of the symbols. Especially Georg Friedrich Grotefend, who by 1802 had managed to obtain 10 of the 37 symbols of Old Persian.

With that information, Henry Rawlinson, an officer of the British East India Company, scaled the cliff of the Behistun inscription in 1835, copied the Persian text and set out to decipher it. He discovered that the first section of the text contained a list of Persian kings similar to the one cited by Herodotus, with the only difference being that the names were in their original Persian form, rather than the Greek transliterations employed by Herodotus. Three years later, in 1838, he had managed to completely decipher the inscription.

In 1843 Rawlinson returned to Behistun. He scaled the cliff again, but this time he was prepared with wooden boards so he could get around the precipice and access the part of the Elamite inscription. With ropes and the help of a child he also managed to climb to the text in Babylonian script and take molds in papier-mâché.

Back in England he shared these materials with other scholars who, working together and separately, finally succeeded from Rawlinson's Persian transcription in deciphering the Elamite and Babylonian parts of the inscription. This milestone, along with the subsequent translation of tablet number 11 of the Gilgamesh poem by George Smith in 1872, were the spark that began the development of modern Assyriology.

The Behistún inscription, Rosetta stone of cuneiform script

The Behistún inscription begins with the autobiography of Darío I, giving an account of his ancestry and lineage. It then recounts the events that followed the deaths of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses II, which led to his accession to the throne.

Long after Old Persian fell into disuse and the meaning of the inscription was forgotten, it was attributed to the Sassanian king Chosroes II, who lived more than a thousand years after Darius.

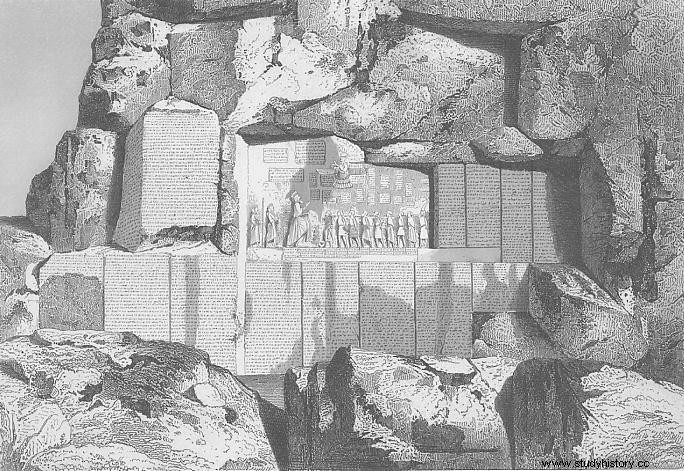

The text is inscribed in three versions, with three different cuneiform languages:Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a variant of Akkadian). For this reason, it supposes for cuneiform writing the same as the Rosetta stone for Egyptian hieroglyphs, the main document that led to its decipherment and understanding.

It is about 15 meters high by 25 wide, and stands 100 meters high on a limestone cliff in the Zagros Mountains on the ancient road that linked Babylon and Ecbatana (capital of Media). The Persian text has 414 lines in 5 columns, while the Elamite includes 593 lines in 8 columns, and the Babylonian 112 lines.

The text is accompanied by a life-size bas-relief showing Darius the Great with a bow, his left foot resting on the chest of a figure, the suitor Gaumata. Two servants serve Darío and 9 other figures stand to his right with their hands and necks tied, representing the conquered peoples.

The first documentary reference we have of the Behistun inscription comes from Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek historian who, after being captured by the Persians in 415 B.C. he became physician to King Artaxerxes II for 17 years. He wrote a history of Persia titled Persica , now lost, but which can be partially reconstructed thanks to other sources. In it he mentions the inscription, indicating that under it there is a well and a garden. But he incorrectly attributes its realization to Queen Semiramis of Babylon, something that later Diodorus of Sicily would also take for granted.

Tacitus also mentioned it, describing some of the monuments at the foot of the cliff, and indicating the presence of a spring. What has been recovered from these monuments in archaeological excavations is consistent with their descriptions.

The text of the inscription is completely illegible from the ground, given the height at which it is located. It is believed that Darío preferred to watch over its conservation, placing it in an inaccessible place, rather than making it legible, something that actually worked. For this, he even ordered the destruction of the rock ledges that had allowed the artisans access to the place, so that no one could ascend to it again.

The full text is translated into Spanish and can be consulted online at the previous link. It starts like this: