The Roman Emperor Constantine II could very well have gone down in history because of, among other things, the mess of names he had:his name was Heraclius Constantinus Augustus, although he also appears as Flavius Constantinus Augustus and in his time he was known as Kōnstantinos Pogonatos, i.e. Constantine the Bearded , although the most usual was Constante, which is actually a diminutive of Constantine. But this character also has a place in the anecdote as he is the last emperor who reconciled his position with that of consul, sent embassies to China and marked the transition from Antiquity to the Middle Ages in Eastern Europe.

Constant was the eldest son of Constantine III Heraclius, who had reigned in the Eastern Roman Empire in an ephemeral way (just four months of the year 641 AD) and in turn had Heraclius as his father, the founder of that dynasty. Regarding her mother, Gregoria, she was also a second cousin of Constantine III and had with her husband another son named Theodosius, pointing out the possibility that there was a third member in the offspring, a sister known as Manyanh. Heraclius's succession was a problem because Constantine III had to dispute it with his half-brother Heraclonas, who was the son of his second wife, Martina.

Constantine avoided the conflict by associating him with the throne, despite the fact that he was a teenager managed by her. But tuberculosis solved the problem by killing him and leaving the throne in the hands of his stepbrother, in a context of serious events, since there were still religious disputes with the growing importance of Monothelitism (a creed that emerged from the attempt to ingratiate Catholicism with the monophysitism) and the provinces of the Middle East fell into the hands of the Arab Caliphate, threatening Egypt.

Heraclonas tried to stop the Islamic expansion but could not and the Egyptian territory was progressively conquered while he only kept the coastal cities, where he accumulated the bulk of his forces. In fact, the inferiority was so obvious that he chose to open negotiations with the caliph. But he didn't give time. The stage of Heraclonas did not last long either:only four more months, when the rumor spread that Martina had poisoned Constantine III and a rebellion broke out demanding that his son share power.

The movement overflowed, leading to civil war and the emperor was deposed and exiled to Rhodes along with his mother, but not before a brutal practice was inaugurated with them that would henceforth be used to apply to fallen rulers:mutilation, that turned the sufferer into a half-man whose appearance, opposed to that of divine perfection, left him incapable of command (at least in theory, since Justinian II, for example, would manage to regain power despite his rhinokopia ). The most common was blinding, because it prevented the victim from leading armies, or castrating to avoid claiming offspring. They cut off Heraclonas's nose and Martina's tongue.

This is how Constans II took command of the empire in 641, when he was only eleven years old. Of course, under the control of a regency made up of senators and led by Patriarch Paul II of Constantinople. The Senate had radically opposed his predecessor and was then experiencing what would be his last period of authentic power, lasting until the young emperor came of age. But this did not come until 648, and meanwhile problems were piling up. The first and most pressing was the unstoppable advance of the Muslims, who did not waste the chaos of the empire.

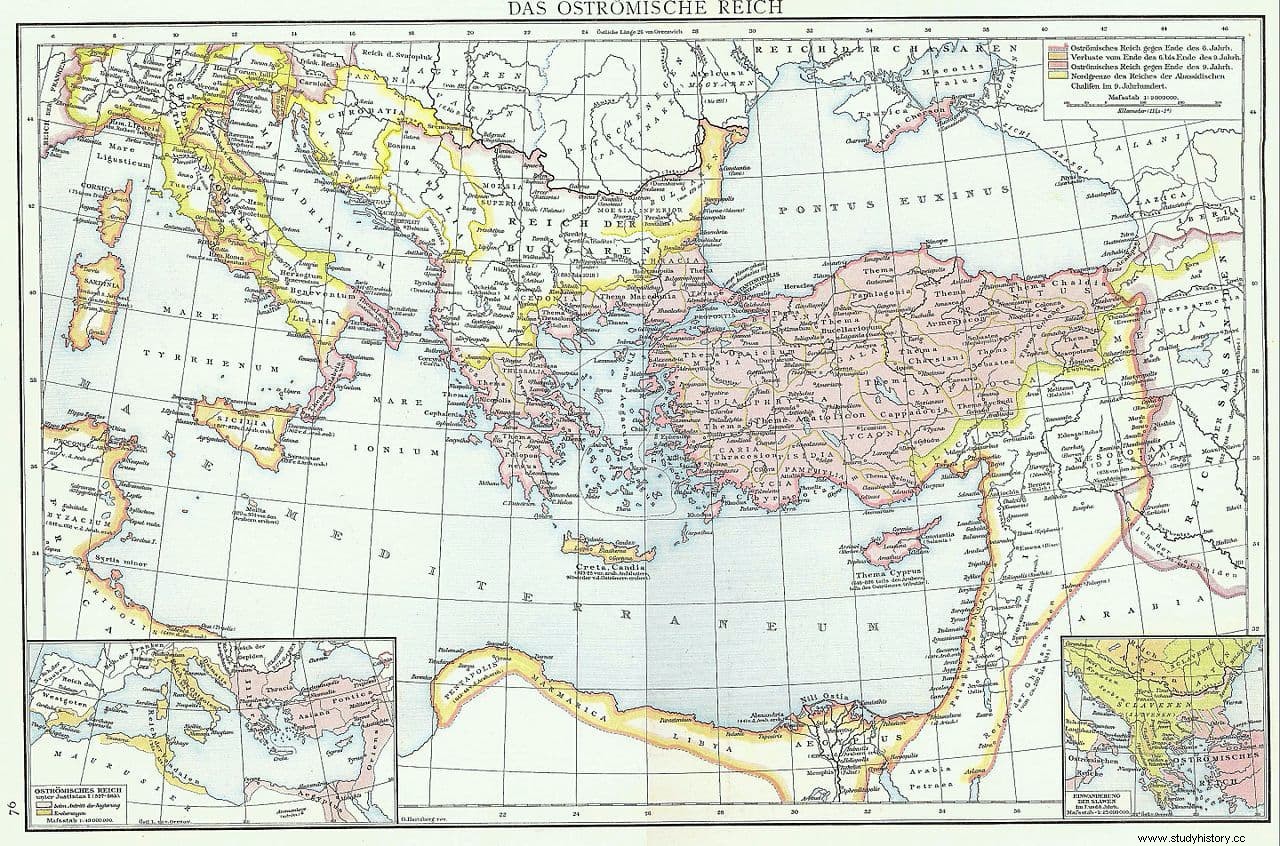

These took over Egypt with some ease in 642, adding it to their conquests of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine. The Byzantines managed to recapture Alexandria in 645 but only for a short time and eventually lost it again. Even worse, the Caliphate organized a large fleet with the aim of taking the Byzantine islands; Rhodes and Crete came under attack, and Cyprus fell to them in 649. At the same time, they secured their control over Armenia and pushed into Cilicia; they only stopped when they agreed to a truce with Constante II.

The emperor, on the other hand, had been in serious trouble within his borders. Married to Fausta, the daughter of the almighty general Valentino who had led the overthrow of Heraclonas becoming the strong man of the empire (he was even allowed to wear purple), he found his father-in-law leading a coup d'état taking advantage of who was the head of the army. However, the move backfired on the military veteran, who got no support, and he ended up lynched by the town around 644.

Constans II himself nearly lost his life in the defense of Rhodes, which took place a decade later, after the disastrous naval battle of Finike, from which he escaped by swapping clothes with an aide. Chance came to his aid in 656, when the caliph died and the Islamic offensive stopped to give way to the subsequent war of succession. That gave the emperor breathing room two years later to stop the Slavs pouring into the Balkans, deporting many to Asia Minor. Also to recover ground in Anatolia, so that the security of the empire seemed guaranteed for the moment. But another internal issue still needed to be resolved:the religious one.

As we reviewed before, Heraclius had tried to ingratiate Trinitarian Christians -who defended the Holy Trinity- with Monophysites -those who believed that in Christ there is only divine nature- through a third way called monothelism, which admitted divine and human nature in one single will. It was a failure in the West, where the Pope refused to compromise, but in the East it was established by decree. At the Lateran Council of 649, Pope Martin I condemned it and rebelled against the imperial edict that forbade debates on the subject. Constant II, fed up, ordered the exarch of Ravenna (where the Holy See was) to arrest and banish him.

The dispute with the papacy did not stop there; it worsened in 663, after the emperor stripped the richest buildings in Rome of their ornaments (including the bronzes that covered the dome of Agrippa's Pantheon) to take them to Constantinople. With this hostile initiative he wanted to demonstrate to Pope Vitaliano, with whom he had established diplomatic relations and who had welcomed him warmly, that he was really in charge and gave his support to Mauro, Archbishop of Ravenna, who aspired to become independent. And it is that Constant was in Italy since 661 and also visiting Rome, something that an emperor had not done for two centuries before.

It is possible that the reason for this trip was to get away from the unhealthy air of Constantinople, which boiled against him after having had his little brother, Theodosius, executed the previous year, suspecting that he was plotting against him because he resented having associated the throne with his sons Constantine, Heraclius and Tiberius. Others suppose that he wanted to supervise the defense of the western Byzantine provinces against a possible Islamic attack and this would have influenced the provincial reorganization, giving rise to the new division in themas (administrative units arising from land around the military camps, given to the soldiers), although most authors believe that this would be his successor.

Keep in mind that the Muslims had finally settled their affairs and, in 661, the caliphate had a new dynasty at the helm, the Umayyad, founded by the former governor of Syria Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan. He immediately launched a resumption of Islamic expansion and, just as he gained territory in the east, he soon also set his sights on Sicily and the area of North Africa that remained under Byzantine rule. Likewise, he aspired to take Constantinople itself, though that last bite proved too big and he failed.

There is, however, a curious review in this regard:the one that appears in the Ancient Chinese book of Tang and the New Book of Tang , two Chinese texts describing what the city was like (detailing its granite walls and a golden statue with an hourglass) and it is said that Mo-Yi (Muawiya) could only extract a tribute payment from the Byzantines. These Chinese sources also deal with the embassies of Fu Lin (Eastern Roman Empire) sent by King Boduoli, who has been identified with Constant II, in the years 643 and 667; diplomatic representatives presented red crystal and precious stones to Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty, also known as Li Shimin.

All this was part of a long history of intercontinental contacts between Daqin, as the Chinese called the Roman Empire, and China. There is evidence of them direct from the year 166 AD, according to the Book of Han , although the Silk Road had already begun to communicate them indirectly at least a century earlier. Let us also remember that silkworms were introduced to Byzantium by two Nestorian monks who brought them from China, as we saw in another article.

In any case, Constante II was in the Italian peninsula and faced the Longobards, who occupied the northern part, being defeated. He then settled in Syracuse, circulating the rumor that he intended to move the imperial capital there, something that perhaps would endorse the theory that he sought to tilt the political axis towards the West. Whatever the cause of that change, if it was real, it cost him his life:in 668, while taking a bath, he was killed by his chamberlain, who hit him on the head with a bucket. His son Constantine IV, who took over, understood the message and kept the capital in Constantinople.