The imposture sums up in History a series of episodes as amazing as they are fascinating and, sometimes, even funny. There are a multitude of individuals who, brandishing impudence as a flag, have elbowed their way into the books for their impudence in assuming alien personalities and living at the expense of it. But it is one thing to invent characters, such as Princess Caraboo or the catalog managed by Stanley Clifford Weyman, and another to impersonate real identities. Real in both senses of the word, as happened with the so-called pseudo-nerones in Ancient Rome.

Actually, it was not a unique case either. If we take a look back, we find the controversy originated in the second quarter of the last century by a mentally unbalanced named Anna Anderson, who claimed to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia, the last survivor of the family of Tsar Nicholas II. The always mysterious Russia had already given birth to another example in 1773, when a Cossack posed as Tsar Peter III to incite a rebellion against Catherine the Great .

Spain had its own cases, both in the 16th century, with the Pastry Chef of Madrigal and the Undercover of Valencia, who presented themselves as King Sebastian I of Portugal and the grandson of the Catholic Monarchs, respectively. And going back a couple of centuries we find Pablo Palaiologos Tagaris, who claimed to be Patriarch of Jerusalem and later used a non-existent belonging to the Savoy dynasty to get him named Patriarch of Constantinople.

Now, there have always been fakers and the trail takes us back to Antiquity, where the aforementioned episode of the pseudo-nerones constituted a primeval and record milestone; first, because the impersonation was of a whole Roman emperor; and second, because there was not one but three tricksters, no less. As can be deduced from the generic name, the victim was Nero, although the damage was received in his memory because he was already dead. In fact, it was the confusing circumstances of his death that caused it all.

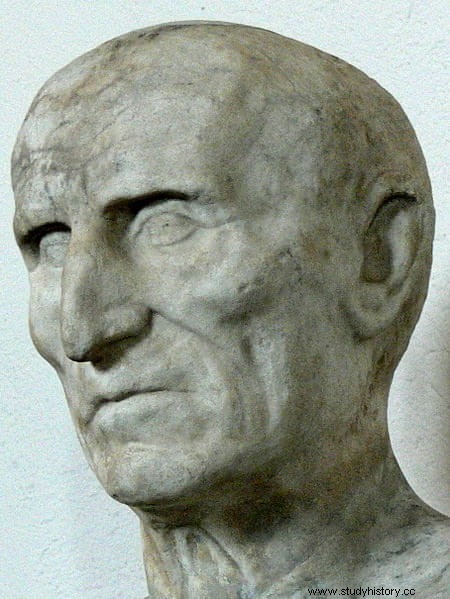

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was the son of the consul Gnaeus Domitius Enobarbus, but he was orphaned at the age of three and his mother, Agrippina (sister of Caligula), then married Emperor Claudius, whose niece she was, getting him to adopt Nero and would make him successor to the imperial throne to the detriment of the rightful heir, Briton. He accepted the position at sixteen years of age and although at first he governed under his maternal influence, he later shook it off, especially after marrying Popea Sabina, who was the one who began to manage him.

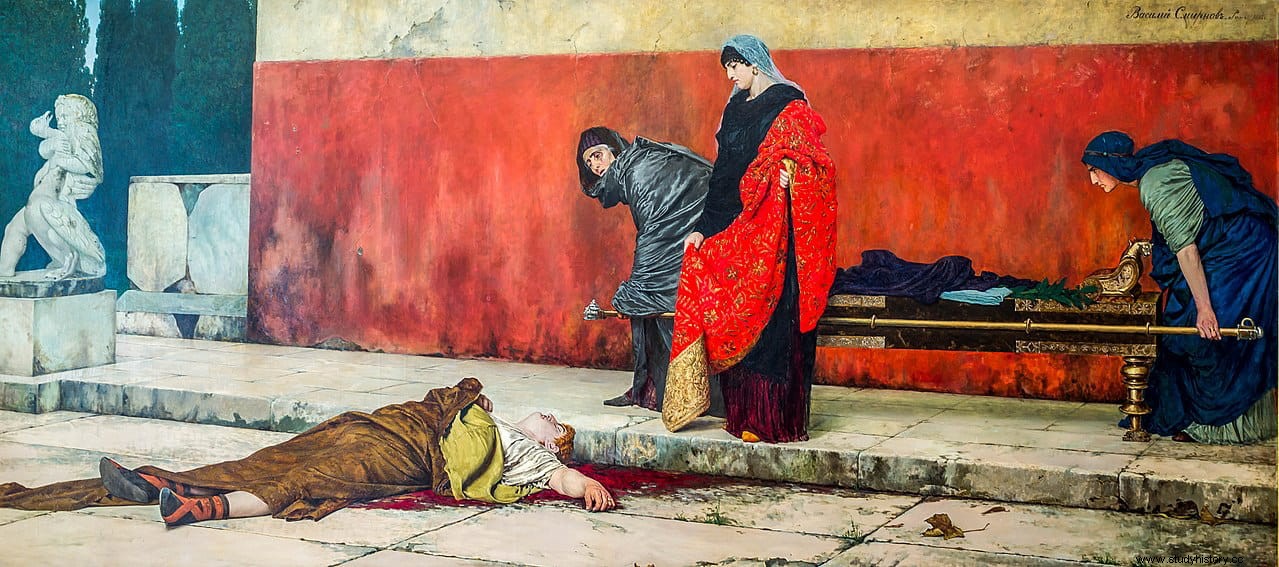

Nero ended up executing Agrippina, making two omens come true:the first had been made by his biological father, saying that nothing good could come of his marriage; the second was Agrippina herself, to whom the augurs had prophesied that Nero would be king but would kill her mother, to which she replied " Occidat, dum imperet!" (Let him kill me as long as he reigns!). Two examples of the capricious Neronian mandate, of which, as happens with Caligula's, it is difficult to determine how much is true and how much is black legend.

Indeed, Nero passes for being the author of the fire in Rome -he could have been, but involuntarily, not to compose odes to the sound of his lyre-, just as he is credited with having his mother and Britannicus assassinated, kicking Poppea to death while pregnant, persecuting Christians... In reality, most of the historiographical sources are from authors who were not exactly sympathetic to him or his politics, such as Suetonius, Tacitus and Cassius Dio, and it does not appear that the issue will be resolved conclusively today .

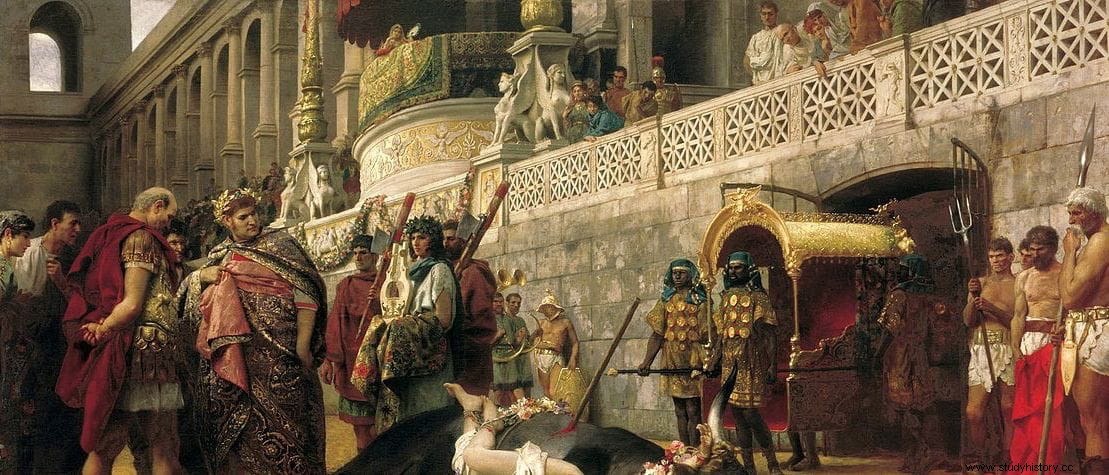

In any case, between the years 67 and 68 AD. there was an insurrection in Gaul Lugdunense led by its governor, Gaius Julius Vindex. The movement was suffocated and Vindex committed suicide, but before that he had asked for help from Servius Sulpicio Galba, governor of the Tarraconense, whom the Senate supported to overthrow Nero, bribing the Praetorian Guard. Nero had to escape from Rome and, being about to be reached, he preferred to take his own life. His death was celebrated by the upper classes -not so much by the people, who had been satisfied with a multitude of initiatives in what has been called the Neronian Revolution- who proceeded to apply the consequent damnatio memoriae .

This, together with the confusing information regarding the body, that he was not granted a funeral worthy of his lineage, that he was not buried in the Mausoleum of Augustus with the other emperors of his dynasty but in a private tomb that the Enobarbos had in the Mount Pincio, the complicated political panorama that followed (with four emperors in a single year:Galba, Otto, Vitellius and Vespasian) and the game of repression-counter-repression that this type of situation brought with it; All this, we say, led to the topicality of a legend that became known as Nero redivivus.

It consisted of the popular belief that Nero would return to claim his throne, since he would not have died but fled to Parthia, where he raised an army. The rumor began to spread at the end of the 1st century and was based on two pillars. On the one hand, the astral chart made for the emperor at birth, according to which he was prophesied that he would lose his heritage but would recover it after a stay in the East; one of the versions that circulated even detailed the place of his revival, Jerusalem.

On the other hand, there were the Sibylline oracles, a collection of books narrated by Sibyl (a famous ancient fortune teller) that chronologically extended from the 2nd century B.C. until V AD and, it is believed, were compiled by Jews and Christians for the purpose of attacking Roman paganism. In fact, over time, the legend of Nero redivivus it was assimilated to the arrival of the Antichrist in Christian environments, identifying the deceased emperor with the Beast that narrates the Apocalypse by matching the famous number 666 with the letters of Nero's name.

But before that, the myth had already spread and settled due to the appearance of the pseudo-nerons, which seemed to confirm it. Suetonius and Saint Augustine are the main sources to know about these impostors, who were three. The first emerged in Achaia (Greece) very shortly after the emperor's death, in the same 68 AD, and the news spread like wildfire because, after all, Nero had visited the region two years earlier on the occasion of the Panhellenic Games (he was honored to be allowed to participate, despite not being Greek).

According to Tacitus, the proverbial credulity of the natives of the country made them easily fooled by someone he described as a slave or at least a freedman, perhaps from Pontus or perhaps from Italy itself, who managed to gather a group of followers among deserters of the army.

With them he embarked for Rome, but a storm threw them against Cythnos (an island of the Cyclades) and there they joined the pirates who used to anchor there. Apparently, they tried to recruit more men from among the legionnaires returning to Italy.

Aware, Galba appointed Lucius Nonius Calpurnius Asprenas governor of Galatia and Pamphylia (two regions of Asia Minor) with the explicit mission of putting an end to that annoying problem. He did so; after defeating the impostor in combat, he ordered that he be beheaded and exhibited the head along the Aegean coast and then sent it to Rome as material proof that he had fulfilled the commission. Only, as there would be occasion to verify later, the revived Nero would grow heads again; ironically, this fit the verses of the Apocalypse :

And it is that during the reign of Titus (which began a couple of decades later) another Nero appeared. This taking the impersonation of him to the extreme, because apparently he appeared in public playing a lyre and singing verses. What's more, they say, he physically resembled the original and that is why he managed to convince a significant number of followers who did not care that his real name was Terencio Máximo, a Roman resident in the Middle East.

Terence cleverly offered an alliance to the Parthians, aware that their king, Artabanus II, resented Rome despite having been raised there (as a hostage) because Tiberius had not only not supported his aspirations to the throne of Armenia but also helped the nobility local to overthrow him in favor of Tiridates III. Although he died soon after and Artabanus regained power, he had to sign a treaty with Rome recognizing his authority. Having Nero as a friend, even if he was a fugitive Nero, could be an asset to play for the future, only...

…Only it wasn't the real Nero, of course. And when the monarch learned of his true identity, outraged by the mockery, he had him arrested and executed. Cassius Dio recounts it in his Roman History , although the narrative is somewhat confusing because the chronology does not correspond to the one used today (Artabanus II reigned from the year 10 to 38, when he died).

However, the Parthians would have the opportunity to support a third impostor a few decades later, during the period of Domitian. So serious was their agreement that it was about to lead to a war against the Roman Empire. This was not the case and Suetonius explains that he was executed, although capturing him earlier cost enough so that the person in charge of the task, Gaius Vetuleno Civica Cereal, governor of Mesia (a Danubian province where the pseudo-Nero operated), also lost his life for order of the emperor, accused of inept.

In fact, it is not known whether Civica tried to tread carefully to prevent the raids against the fraud from stirring up the Dacians (in fact, between 86 and 89 AD, Domitian would have to wage war against his chief, Decebalus, which was very hard for the Roman legions) or if he was involved in any of the frequent conspiracies that began to appear in the empire. The fact is that that was the last revived Nero of which we have documentary evidence.