This formidable adversary did not wield sword or spear against Rome, but rather put his enormous scientific talents at the service of his fatherland to strike fear into his enemies. As has happened so many times in history, how many great advances in science and technology will not have a purely warlike background? That is the case of Archimedes of Syracuse , one of those names that present themselves. Genius of mathematics, physics and astronomy, his ingenuity put the Roman troops besieging his city in serious trouble. Let's get into the matter. Son of the astronomer Phidias and relative of King Hieron II, as Plutarch wrote in his “Life of Marcellus ”, Archimedes was born in 287 BC. in Syracuse, an uncertain date because the only source we have left is the Byzantine historian Juan Tzetzes and, according to him, Archimedes lived seventy-five years and the date of his death is known for sure.

Little is known about his personal life, whether he had a wife or children. Diodorus Siculus maintained that Archimedes was educated in Alexandria, at that time the cradle of science throughout the Mediterranean. Perhaps he went there, soaking up the knowledge that the Museum and the Library treasured, where he studied mathematics and engineering. It is also not known at what age he returned to his native Syracuse, but it is certain that he maintained good relations with the Egyptian rulers, since one of his immortal inventions, the "Archimedean screw" was designed to extract the water that accumulated in the bilge of the enormous Syracusia , the largest ship of its time, designed by Archimedes himself at the request of King Hieron and which ended up being sent to Alexandria as a gift to King Ptolemy III Euergetes.

Syracusia

In the year 214 B.C. the situation in Syracuse, and in the whole of Sicily, was very delicate. Hannibal was still in Italy fighting against the legions of Gaius Claudius Marcellus, but the landing of new Carthaginian troops in Agrigento and the defection of the Council of Syracuse, until then pro-Roman, truncated the tense balance. King Hieronymus, close to Rome, died under strange circumstances and two Carthaginian-born brothers named Hippocrates and Epicides took control of the city, purging friends of Rome and deliberately entering into a new alliance with Carthage. When Marcelo landed in Sicily, events took a turn, the two brothers were expelled from Syracuse and ended up taking refuge in Leontino. The fierce Roman repression of the rebels, accompanied by the cold-blooded murder of two thousand Roman deserters ordered by Marcellus himself, created a pro-Carthaginian movement throughout eastern Sicilian that concluded with the opening of the gates of Syracuse to the two brothers. and the declaration of open hostilities with Rome.

It was at that moment that our protagonist entered the scene. Marcellus exhorted the inhabitants of Syracuse to lay down their arms and surrender the city. He was unsuccessful and tried at first to launch an assault against her strong walls. The problem is that not only spears, boiling oil, stones or arrows sprouted from its battlements. The old Archimedes put all his talent and ingenuity at the service of his country, installing all kinds of war machines capable of lifting ships or setting them on fire from a distance, causing panic among the Roman troops the mere appearance of a mast or a pulley between the defenses .

The assault ended up becoming a blockade, since it was reckless to approach the city with all those mechanisms ready to sink the Roman fleet. Two of them are well known to us, the “Archimedean Claw ” and the “Heat Ray ”. Let's see what they consisted of:according to Polybius, Archimedes designed the manus ferrea (iron claw) to be used when the Romans brought their ships close to the walls of the upper city, and from the battlements appeared a kind of crane at the end of which hung a huge metal hook. That artifact fell on the ship, embedding itself in its bow. It was then hoisted and swung from the battlements, lifting it up and causing water to enter through the stern openings. Then the hook was released abruptly, causing the ship to fall suddenly, list due to the water that had entered it, and then sink. The heat ray consisted of using burning mirrors (a large concave mirror) to concentrate the solar rays that reflected on a single point of the ship, preferably sails or rigging, causing a fire on board. Contemporary tests carried out recreating both devices are conclusive:these ingenious weapons are feasible.

It was already the summer of 212 B.C. After a tedious blockade of two years, everything seemed stagnant until, perhaps by chance or due to the denunciation of some traitor, Marcelo discovered a stretch of wall that was more accessible than the others and, on a night when the Syracusans were celebrating a great party, broke into the new neighborhood of Epipolas, then pillaged the adjacent neighborhoods of Tyche and Neapolis. Epicides shut himself up in old Ortygia, maintaining the Syracusan resistance between the island and Achradina. The Carthaginian Himilcon came soon after to the aid of his allies, but all his attacks were repelled by Marcellus's legions.

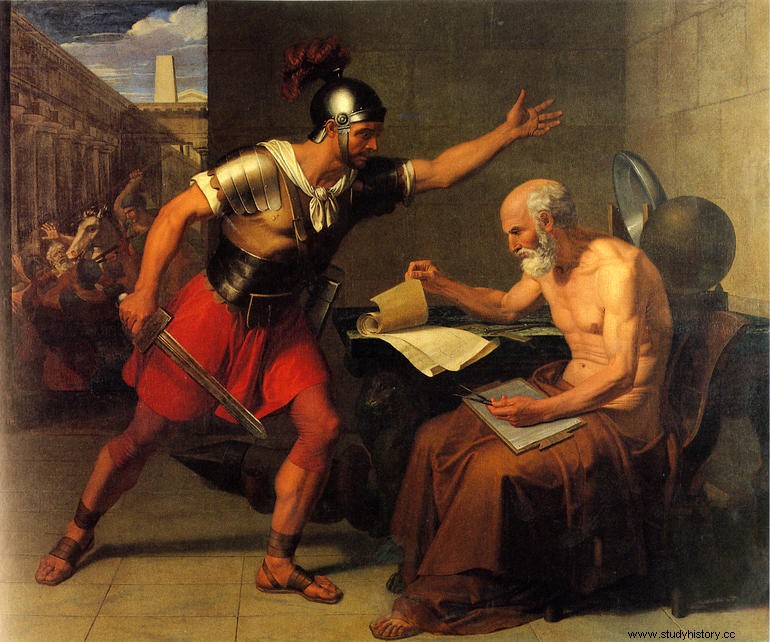

The situation stagnated again, but this time the enemy to beat did not carry a shield or sword. Due to the unhealthy environment and so much death and destruction everywhere, a plague was unleashed that devastated Carthaginians and Romans alike, leaving the former without many of their commanders. After Himilcón's last failure to release the siege, one of the Hispanic mercenary leaders defending Syracuse, named Méricus, secretly negotiated advantageous conditions with Marcellus if he would open the gates of Achradina to him. It happened like that. The entire city, including Ortygia, fell into Roman hands and was thoroughly looted. Amid the confusion, Epicides escaped to Agrigento in search of Bomílcar, another Carthaginian commander, never to be heard from again. Marcellus fleeced the city's treasure and its most famous works of art, taking them with him to Rome to display at his triumph. There were many victims of Roman pillage, but the most notorious was that of the genius who had kept the fleet at bay for so many months. Despite the express prohibition of violence ordered by Marcelo, Archimedes died during that final assault.

According to Plutarch there were in his time several versions of how it happened. It seems that the mathematician was working in his study when a Roman legionnaire broke into it and, perhaps due to ignorance of the sage's explanations in his native Greek, perhaps because he thought that those artifacts were good loot, perhaps because of the dangerous mixture of all this, the fact is that the gladio of the soldier reaped his life. Tito Livio said that the last sentence of Archimedes was:

“Noli turbare Círculos Meus”

(Don't bother my circles!)

According to the Roman historian, Archimedes pronounced it when that soldier interrupted his work, but Plutarch does not even mention it in his writings. Perhaps it is part of the legend that surrounds this timeless genius.

Collaboration of Gabriel Castelló, author of Archenemies of Rome

My latest book is now on sale on Amazon: