Both Berbers and Slavs sought land and power to improve its previous situation in the Maghreb. All tried to reproduce in the small states that formed the Umayyad despotic scheme, which caused some of the territories to acquire a certain pre-eminence over their neighbors. For this reason, many times they had to ask for help from the Christian kingdoms, which received their military support in abundance, causing the pre-existing balance between the Andalusians and these to break. The process of segregation and organization of the first taifas(2) was quite fast. For fifty years the payment of the pariahs(3) for protection to the Christians of the north propelled their wealth and plunged the south into a deep crisis(4).

The period of the first taifas It would end with the assault of Alfonso VI on Toledo, which caused the rupture of the Tagus border and the flight to the south of thousands of families. This meant the worst social rupture in al-Andalus, where a stable and diverse human base had found its balance under the power of emirs and caliphs. A massive migration of Berbers and slaves grouped under the leadership of different generals was the cause of the imbalance(5). In addition, the mismanagement of these groups, which should have been settled on the borders where their bellicosity would have been of benefit, fueled quarrels between those close to power because they were allowed to participate in Cordovan politics. Then the degradation of the Umayyad dynasty takes place, the loss of its ideological support, the structural fabric of Islam.

The vast majority of the population were Hispanic-Goths , who converted to prosper in Islamic society. The Jews remained culturally segregated, however, they had assimilated more intensely. The slaves, who did not know Arabic, remained in unintegrated groups, mercenaries, without idiosyncrasies or land until they created their own taifa.

The Arabs they formed the most homogeneous group and the one that went on to form the political, social, religious and economic elite. His attitude was segregating towards other minorities(6), which caused interracial conflicts, especially with the Berbers. These represent the second most widespread human group, which arrived in the Peninsula in successive waves and went through different stages of integration and social predominance. They had to be Islamicized very quickly and were organized in cavalry squadrons with strong internal cohesion. They barely integrated into Andalusian society and mainly devoted themselves to conquest and loot(7).

The family of Abū Zayd or Abū Muṣʻab ʻAbd al-ʻAziz al-Bakrī , father of our character, belonged to the most prominent in the Huelva region. From the beginning of the civil wars (fitna) of the 11th century, ʻAbd al-ʻAziz is recognized as sovereign of Huelva and Saltés in 403 H/1012-1013. The sources mention the economic and maritime importance of Saltés and archeology has revealed its mining importance.

References to the prosperity of this taifa are repeated in the sources until the arrival of al-Muʻtaḍid of Sevilla. As soon as he conquered neighboring Niebla, he headed towards Huelva in 1051. ʻAbd al-ʻAziz tried to stop him through pacts and gave him Huelva so he could retire to Saltés, but al-Muʻtaḍid did not respect the pact and al-Bakrī's family(8) had exile to Córdoba, ʻAbd al-ʻAziz dying in the year 1058(9). In addition to being an author, al-Bakrī was a courtly intellectual linked to political activity.

al-Bakrī. Formation, activity and legacy

According to Ibn Baškuwāl , he developed his activity in different cities, such as Almería, where he learned his geographical knowledge from al-ʻUḏrī. However, his courtly activity stands out in the court of the Sevillian taifa at the time (10) of al-Muʻtamid , successor to al-Muʻtaḍid. His poetry manifests his closeness to the circles of power. This was a propitious moment for the cultivation of letters in the different courts.

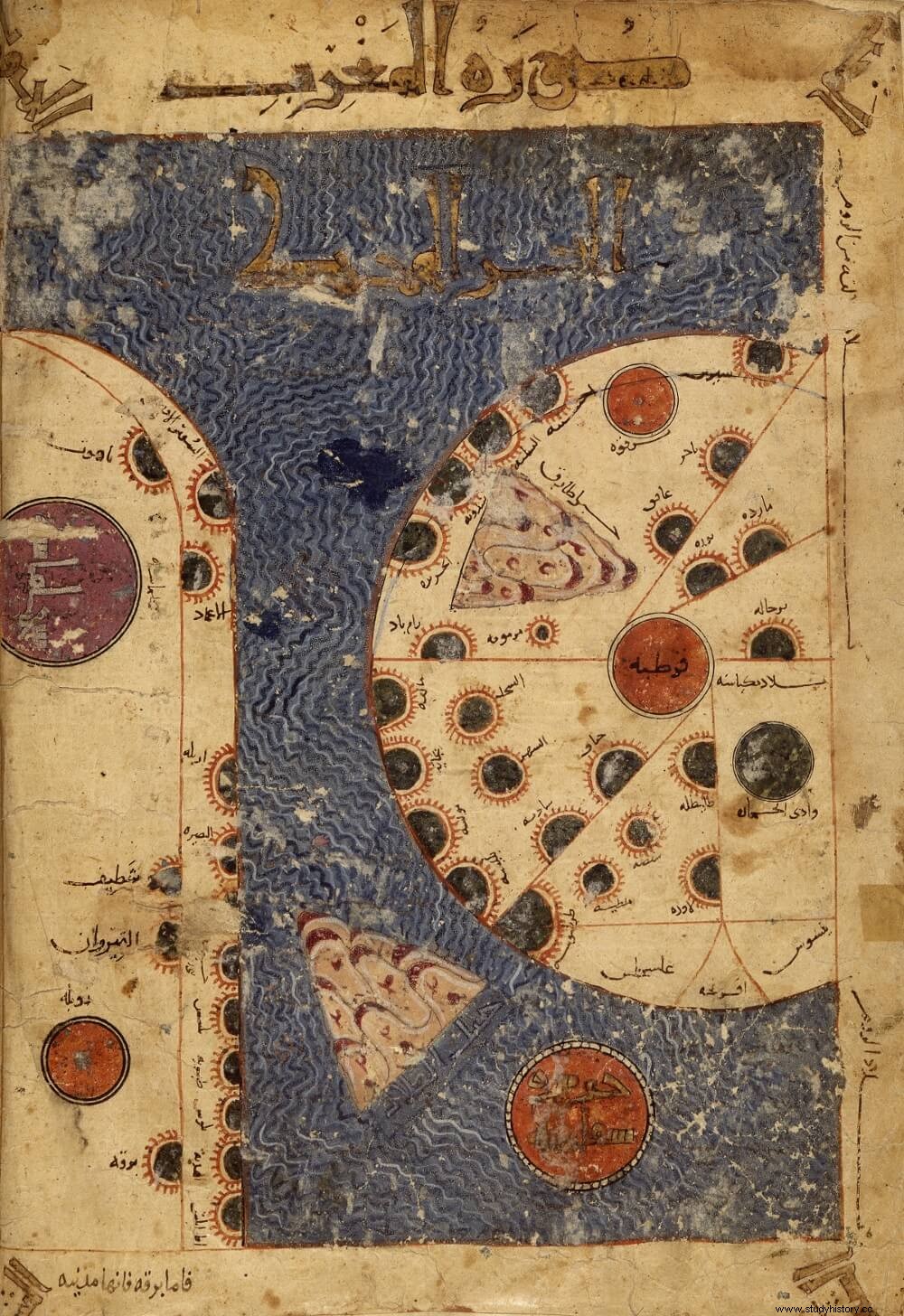

His training of him (11) begins with his transfer to Cordoba. Ibn Baškuwāl mentions four of his teachers:the Cordovan chronicler Ibn Ḥayyān , the geographer al-ʻUḏrī already mentioned, al-Muṣḥafi , alfaquí, litterate and linguist, and al-Barr , specialist in fiqh or Islamic law(12). Two works stand out from his geographical production (13):the Muʻjam mā istaʻcham , a geographical dictionary that is still preserved and deals with toponymics of the Arabian Peninsula; and the Kitāb al-masālik wa-l-mamālik :

Chejne insists that al-Bakrī never left of al-Andalus and that he based his work on information compiled from other authors, both Western and Eastern. Some of them were Ibn Rustah, al-Masʻūdī, Muḥammad Ibn Yūsuf al-Warrāq, al-Rāzī, Ibrāhīm Ibn Yaʻqūb al-Isrāʼ ilī, al-ʻUḏrī, etc.

There are several published studies on the figure of Abū ʻUbayd al-Bakrī and among the sources that inform us about his life we have bio-bibliographical dictionaries and chronicles. The first are biographies of the character contained in repertoires of ulema and alfaquíes, a genre of medieval Arabic literature that only provide some data. His production is characterized by its breadth of themes and its variety, a total of twelve works. He highlights his linguistic production, although nowadays he is known as the main geographer of al-Andalus. Supplements are attributed. In the Andalusian repertoires, the dictionary of wise men from Cordoba Ibn Baškuwāl stands out. (14) (1139).

Of the rest of the biographical repertoires, only that of al-Dabbī (1202/1203), mentions our character, providing a date for his death nine years later than the one presented in the aforementioned work. Ibn al-Abbār practically reproduces Ibn Baškuwāl's work in its entirety and adds fragments of texts from al-Bakrī's work, as well as a paragraph by the anthologist Ibn Jāqān(15).

Regarding oriental repertoires(16), our character is mentioned in the works of Yāqūt al-Hamawī (1229); that of al-Safadi (1297-1363); and that of al-Suyūtī , which indicates a date of death close to that of al-Dabbī.

We also have the chronicle of Cordovan Ibn Ḥayyān (1076) and a fragment of an anonymous chronicle of the work of the North African Ibn ʻIḏārī (14th century). Both mention our author's belonging to the Huelva branch of the Bakrí family.

Another important source is the literary anthology of Ibn Bassām , with a chapter in which he provides various texts by the author and some of his poems.

Based on all of them, we have only been able to obtain three certain dates(17) in reference to al-Bakrī's life:the date of his death in 1094, when he left Saltés to go to Córdoba in 1051, and the composition date of the geographical description of him in 1067/1068. His date of birth remains unknown.

By way of conclusion, we can say that al-Bakrī's work has a fundamental value as a source of geographical and historical character. for the knowledge of Muslim Spain during the Middle Ages. The Kitāb al-masālik wa-l-mamālik , despite having been preserved in a fragmentary way, provides us with a series of data that allow us to get an idea of how the Andalusians themselves saw their environment and their past, as well as being an important sample of how far their cultural and scientists.

However, when facing the analysis of this type of sources, we must never forget that their authors belonged to a specific social context and that the result of their work had a specific purpose, which was often at the service of those who held power.

Bearing all this in mind, we can approach the author and his texts and carry out an exhaustive analysis that will allow us to better understand our past and assess the Andalusian legacy that it has had in its fair measure. a great importance in the construction of our present.

Bibliography

- Álvarez Palenzuela, V. A. (2011):History of Spain in the Middle Ages , Editorial Planeta S.A., Barcelona, 915 pp.

- Bonnassie, P., Guichard, P. and Gerbet, M. C. (2001):The medieval Spains , Editorial Crítica S. L., Barcelona, 368 pp.

- Carrasco, J, Salrach, J. M., Valdeón, J. and Viguera, M. J. (2002):History of medieval Spains , Editorial Crítica S. L., Barcelona, 380 pp.

- Chejne, A. G. (1974):History of Muslim Spain , Ediciones Cátedra S. A., Madrid, 432 pp.

- García Sanjuan, A. (2002):«The polygrapher from Huelva Abú ʻUbayd al-Bakri», in Aestuarja Research Magazine , Diputación de Huelva, year 9, no 8, pp. 13-34.

- Monsalvo Antón, J. M. (2014):History of Medieval Spain , University of Salamanca Editions, Salamanca, 434 pp.

- Viguera Molíns, M. J. (1992):The Taifa kingdoms and the Maghreb invasions (Al-Andalus from XI to XIII) , Editorial MAPFRE S.A., Madrid, 377 pp.

Notes

(1). Monsalvo Antón, J. M. (2014):History of Medieval Spain, University of Salamanca Editions,

Salamanca, 434 pp.

(two). Monsalvo Antón, J. M. (2014) …

(3). Ibid.

(4). Ibid.

(5). Ibid.

(6). Ibid.

(7). Viguera Molíns, M. J. (1992):The Taifa kingdoms and the Maghreb invasions (Al-Andalus from XI to XIII), Editorial MAPFRE S. A., Madrid, 377 pp.

(8). Viguera Molins, M. J. (1992) …

(9). Ibid.

(10). Ibid.

(eleven). Ibid.

(12). García Sanjuan, A. (2002):The polygrapher from Huelva, Abú ʻUbayd al-Bakri, in Aestuarja Research Journal, Diputación de Huelva, year 9, nº 8, pp. 13-34.

(13). Chejne, A. G. (1974):History of Muslim Spain, Ediciones Cátedra S. A., Madrid, 432 pp.

(14). Garcia Sanjuan, A. (2002) …

(fifteen). Ibid.

(16). Ibid.

(17). Ibid.