But Pizarro was not satisfied with fortune, especially after learning of the conquest of the great Mexica confederation by his nephew Hernán Cortés (see Awake Ferro Modern History #12:The Conquest of Mexico ); he longed for another great empire to conquer and a rulership with which to polish his lineage. Therefore, while others were discouraged by the meager results obtained until 1524, he knew how to keep waiting for his great opportunity.

The expedition to the Levant

On May 20, 1524, in Panama, the partners Hernando de Luque, Diego de Almagro, Pedrarias Dávila and Pizarro himself they signed the first Levante Company. The document specified that the man from Trujillo would lead an expedition with the rank of "lieutenant of captain general" of the governor of Tierra Firme. The data is very illuminating, since, from the very genesis of the process, Diego de Almagro from La Mancha assumed the role of auxiliary. The entire expedition depended directly on Governor Pedrarias Dávila, who became involved in it. The investment and future profits would be divided into four parts. After the signing of the agreement, the teacher Hernando de Luque officiated a mass and divided the host into four equal parts. From that moment they enjoyed not only the temporal blessing but also the spiritual one, which, in those times, was still a guarantee.

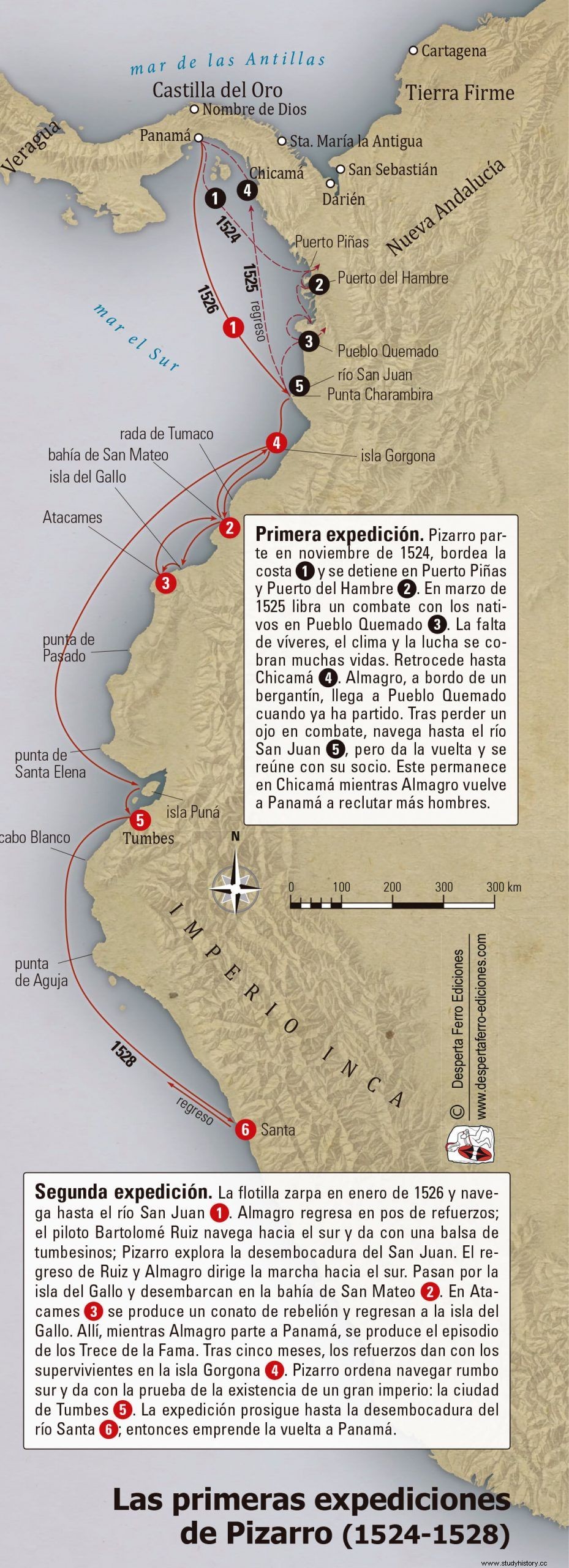

The expedition would take a few months, since it was not easy to prepare a company from Tierra Firme, given the scarcity of ships and men willing to enlist. Finally, on November 14 of that same year, 1524, the Trujillo man released moorings with the ship Santiago -popularly known as Santiaguillo-, taking with him a total of 112 Spaniards and a handful of Nicaraguan Indians. After a little over two months of crossing they arrived at the port that was later called Hunger, where many lost their lives from sheer starvation and some were injured, including Pizarro himself. Almost a third of the expeditionaries perished, since the natives systematically practiced the scorched earth policy to defend themselves.

Since they found no food, the expeditionaries decided to send Captain Gil de Montenegro to Pearl Island for provisions while Pizarro remained on land with eighty men. Although they estimated that the ship would return in a week, in the end it took a month and a half. In that lapse another thirty men died, some of hunger and others at the hands of the aborigines who periodically attacked them. After innumerable hardships, and when they were on the verge of despair, the ship captained by Montenegro appeared on the horizon, returning with some men and holds full of food. After eating heartily and recovering adequately, in March 1525 they decided to continue their journey.

The next town they reached was Punta Quemada , who found desert at the time that the natives attacked them from outside and caused several casualties among their ranks. All these hardships seriously undermined the morale of the expeditionaries, forcing Pizarro to consider returning. The man from Trujillo made the decision to return, but not to Panama, but to the nearby town of Chochama to, from there, send Nicolás de Ribera el Viejo with the battered Santiaguillo to Panama, in search of reinforcements.

Meanwhile, Diego de Almagro had outfitted the ship San Cristóbal with provisions and 64 refreshment men, and set sail in search of his partner. They must have crossed paths with Santiaguillo, but, unfortunately for everyone, they did not see each other. Almagro landed right in the same port from which his partner had fled, with such bad luck that the natives attacked them. Several Spaniards were injured, including Almagro himself, who lost his right eye. And it could have been worse, because they would have finished it off on the ground had it not been for the intervention of Juan Roldán and an African slave owned by the latter. After recovering, they continued the day to meet Pizarro. Finally, both partners managed to meet in Chochama, where they agreed that the Manchego would go to Panama to help Nicolás de Ribera in the search for reinforcements while Pizarro remained waiting. The idea was to prevent everyone from considering the day a failure, although he was probably also embarrassed by the idea of showing up at the isthmus empty-handed. The balance could not be more hopeless; not only had they not obtained significant benefits, but almost half of the expeditionaries had lost their lives.

New hardships

Despite the absence of the man from Trujillo, everyone in Panama interpreted that luck had eluded him. This was still a serious problem, first because Pedrarias Dávila, rightly, considered the expedition a failure and, second, because it was very difficult to recruit new men and get money for the new shift. Finally, the second expedition sailed from the isthmus in mid-January 1526 with 110 men enlisted by Almagro, who joined the fifty troops that remained with Pizarro. The naval means were limited to the two ships of the first voyage, the Santiago and the San Cristóbal, as well as three support canoes for the landings.

In the first days of January they arrived at Pueblo Quemado and had their first encounter with the natives. After several days of fighting they had to re-embark without loot after burning down the town – hence the name. They then passed through the islands of Las Palmas and La Magdalena, and through other ports, without much success. In a stroke of luck that served to raise morale, there was no resistance at the first place where they landed, and after its inhabitants abandoned it, they were able to steal to their heart's content and obtained a booty of some 15,000 gold pesos. However, it did not take long for grief to return to haunt the head of the host in the face of so much setback and the repeated attacks of the indigenous people, who always received them from war.

The Trujillo decided to send his partner Almagro back to Panama in search of food and, if possible, reinforcements, while the pilot Bartolomé Ruiz de Estrada continued reconnaissance from the coast to the south. After a time, the pervasive famine it got worse again; some perished from hunger or disease, and others at the hands of the natives.

In the midst of the capsizing, at the end of 1526, Bartolomé Ruiz returned with excellent news:he had sighted a raft with a small sail that showed it belonged to a superior civilization. To make sure, they arrested his crew, two boys and three women. Once questioned, they obtained another crucial piece of information:it was a commercial vessel in which they transported various Inca manufactures to exchange them for crimson coral. Likewise, they said they were natives of Túmbez and subjects of a great lord.

The news was hopeful at last; However, shortly after, Almagro returned from Panama with less flattering information:the Segovian Pedrarias Dávila had been dismissed and the new governor, Pedro de los Ríos, did not trust the Levante company. However, since he brought some reinforcements and plenty of food, they decided to continue the journey. They landed in the small town of Atacámez, in the current state of Ecuador, and put its inhabitants to flight. Unfortunately, they did not find any considerable loot here either. Many of the expeditionaries, sick and exhausted, became desperate again and insistently requested to return to Panama. So much so that there was even an attempt at rebellion, although in the end it was not carried out for fear of failure. The two partners discussed the continuity of the company and the person who should return for reinforcements. Having overcome their personal misgivings and convinced of the need to move on, they agreed that, as on other occasions, it would be Almagro who would return for reinforcements while the man from Trujillo took refuge on the island of Gallo, where there was hardly any food, but they were safe from the indigenous rush.

The myth of the island of the Rooster it arose when the new governor of Panama, Pedro de los Ríos, decided to send an expedition to bring back the bulk of Pizarro's force. The deprivations had been of such magnitude that, apparently, some men managed to send the new governor a hidden message of help in which they complained about the unfortunate situation they were experiencing and expressed their desire to return. Pizarro partially accepted the decision and allowed the return of those who requested it. Instead, he would resist, knowing that his withdrawal meant not only humiliation and ruin, but also the end of a dream he had fought for for decades.

The Thirteen of Fame

Pizarrista historiography has idealized the events on the island of Gallo to extol the talents of the Trujillo native. Hernán Cortés supposedly burned the ships in Veracruz and blurted out to his men the famous phrase:"whoever wants to be rich should follow me." How could it be otherwise, Pizarro did the same on the island of Gallo. According to the chronicles of the time, the man from Trujillo, who wanted to continue, had an inspiration:with the point of his sword he traced a line on the sand of the beach and addressed his soldiers. Pointing in the direction of Panama, he told them “this is where you go to Panama to be poor”, and immediately afterwards, pointing to the island itself, he told them that there they would find hunger and misery today, but wealth and fame tomorrow, and he blurted out:“Let those who are brave follow me!” . Most of the men ran to embark on the aid ship, captained by Juan Tafur, with such impetus, said one chronicler, "as if they were escaping from the land of the Moors."

Only thirteen men remained with the man from Trujillo. The first to cross the line were Pizarro himself and the senior pilot Bartolomé Ruiz de Estrada, who were followed by the remaining thirteen. It was the month of May 1527 and thus began the legend of the island of the Gallo. Of a total of eighty-five men, only thirteen remained with Pizarro, that is, around 15%. It is true that many of those who left rejoined later, on the third day, or later, and achieved a certain fortune.

But let's break down the legend step by step. Obviously, the narration shows a theatricality that is difficult to believe, even though historiography has been in charge of repeating it ad nauseam. Like most legends, however, it contains an underlying truth that we can verify by chroniclers such as Francisco de Jerez, who was an eyewitness. The reality was very harsh and no one wanted to stay in a place where they had only found hardships. There was still no gold, and instead what they did suffer was chronic famine, as well as injuries at the hands of the warlike Indians they encountered at every turn. Until 1525 they barely managed to obtain a thousand pesos of gold, a true ruin from the economic point of view, since they were not even enough to pay for the ships prepared. No one in their right mind wanted to risk their lives for nothing, so almost everyone wanted to return to Panama and, according to López de Gómara, "rejected Peru" and its false riches.

Traditionally it has been affirmed that only thirteen remained, or at least those are the ones remembered by Francisco Pizarro, although Girolamo Benzoni speaks of fourteen, Antonio de la Calancha of twelve and Francisco de Jerez, secretary of the Trujillo, expands their number to sixteen. They are all partly right; Fifteen people passed the line, counting Francisco Pizarro and the senior pilot, Bartolomé Ruiz de Estrada. The latter was with the Thirteen, but was sacrificed by Pizarro so that, in his name, he would negotiate the continuation of the company with the governor. The two languages or interpreters, Felipillo and Manuel, also necessarily stayed. Thus, given that the pilot Bartolomé Ruiz had to go to Panama, they crossed the line fifteen, but fourteen remained –as Benzoni says– or sixteen, if we include the two tongue Indians, which also proves Francisco de Jerez right.

The list with the specific names of the Thirteen of Fame Various chroniclers reflect it with few variations and, in addition, it appears reproduced in the capitulation of Toledo in 1529, in which the Trujillo asked for nobility for all of them or, if they possessed it, the rank of knights with golden spurs. Their names are as follows:Bartolomé Ruiz, Cristóbal de Peralta, Pedro de Candía, Domingo de Soraluce, Nicolás de Ribera, Francisco de Cuéllar, Alonso de Molina, Pedro Halcón, García de Jaén, Antón de Carrión, Alonso Briceño, Martín de Paz and John of the Tower. The first of them, Bartolomé Ruiz, although he crossed the line, marched with Juan Tafur to help Diego de Almagro organize reinforcements. Therefore, in any case, it is plausible to think that there were some more, perhaps the sixteen cited by Pizarro's always reliable secretary, and that the thirteen, including his captain, who appear in the capitulation of Toledo, are only the survivors of that company.

It does not seem, however, that they stayed on Gallo Island for long, as they soon decided to move to Felipe Island, known shortly after as Gorgona Island, which was somewhat better provisioned. This was about a hundred kilometers from the island of Gallo, which was still a long journey at a time when means of transport were very limited and forces were tight, but it was worth it, because it had fresh water , as well as abundant hunting and fishing, so obtaining food was affordable.

There they waited for a little over two months for the return of Diego de Almagro . According to Benzoni, to the few who remained with him, Pizarro "thanked them very much, making great promises and begging them to be patient" until the arrival of reinforcements. None of them lacked tenacity, as they suffered all kinds of calamities, such as famines and torrential rains. According to the Inca Garcilaso, they fed almost exclusively on shellfish and snakes and "other vermin", and were in an extreme situation when Bartolomé Ruiz de Estrada appeared on the horizon. The reinforcements had taken no less than seven months, so they were received with emotion and joy. They brought food to satisfy their hunger, but very few reinforcement men, proof of the little or no confidence that the company led by the Trujillo aroused at that time. Given that the new governor had given them six months to return and only half had passed, Pizarro arranged for the pilot Bartolomé Ruiz to reconnoiter the coast to the south.

The discovery of Túmbez

In November 1527 they left the Gorgona guided by the Tumbesian Indians, who could now act as interpreters. Fate would soon smile on them. Led by the experienced pilot, they continued south and anchored in the Gulf of Guayaquil, where dozens of Indians crowded the shore to gaze at the strange floating bulk of the newcomers. Until then everything had been calamities; From then on, the efforts and suffering would continue, but along with them the best of stimuli would appear, some samples of the long-awaited golden metal.

After passing through Chira, while they spotted some rafts of Tumbesians who were going to fight against those from the island of Puná, they heard about the city of Túmbez , which was said to be very opulent. Pizarro met with an orejón – a name given to Quechua officials – who, before leaving, asked him for some men to take with him to show them the aforementioned city. The captain chose Alonso de Molina and a black companion. These were the first to visit the city, which seemed good-looking to them, with its stone houses and some important buildings, including the fortress. Molina's information so fascinated the man from Trujillo that he wanted to verify it and sent a second delegation headed by Pedro de Candía, a gunner from Badajoz, whom he considered a person "of good ingenuity." He managed to enter without bloodshed and was impressed by the supposed greatness of the city. Actually, it wasn't much, but it was considerably more than the towns they had seen so far, and it had a magnificent temple dedicated to the sun. And what was even better, some people from Tumbes told him that they depended on a great man who lived many days away from there. The artilleryman was so impressed that he took some llamas and Indians and returned to Pizarro, before whom he magnified what he had seen.

The man from Trujillo believed he had found what he had been dreaming of since his arrival in Panama almost two decades ago. That is why he did not even stop to check the veracity of the story. His dream had come true. After exploring another stretch of coast to the south, he believed the time had come to return to recruit more men and begin the conquest of that great empire. He was received by Governor Pedro de los Ríos with honors, while rumors of the existence of a rich kingdom to the south circulated throughout all the confines of Central America. According to Cieza de León, in Panama there was no talk of another. However, when Pizarro raised with Governor Pedro de los Ríos the need to organize a new company, he refused, since he did not intend to depopulate one governorate to populate another, especially with the great human cost that the Levante conference had had until then. .

The conclusion of the three partners, especially Francisco Pizarro, could only be one:it was necessary to go to Spain to achieve a capitulation . At last they thought they had found the golden dream they had been looking for. Until then, the expeditions had been a complete failure, at least from the economic point of view. Only Diego de Almagro declared having spent more than 30,000 gold pesos out of his own pocket in the first two days. The three partners, who before 1524 were wealthy people in Panama, were in 1529 almost bankrupt and heavily in debt.

Primary sources

- Cieza de León, P. (1985):Chronicle of Peru. Madrid:Sarpe.

- Jerez, F. de (1992):True relationship of the conquest of Peru. Madrid:History 16.

Bibliography

- Bust Duthurburu, J. A. del (2000):Pizarro, 2 vols. Lima:Ed. Cope.

- Goligorsky, L.; Morales Padron, F.; Micheluzzi, A. (1992):Francisco Pizarro in Peru. The thirteen of the fame. Barcelona:Fifth Centenary.

- Mayoral, J. A. (1994):The Thirteen of Fame or the conquest of Peru. Madrid:Anaya.

This article was published in the Desperta Ferro Historia Moderna #36 as a preview of the next issue, the Desperta Ferro Historia Moderna #37:The conquest of Peru.