In a Europe convulsed by revolutionary wars and four coalitions[1] that would have tried to overthrow the Gallic contingent, the press turned out to be a fundamental element on the battlefields and in the daily life of the citizens of the empire that was being formed. The Confederation of the Rhine, the Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Naples or the Swiss Confederation were just a small sample of the great space that made up the First French Empire from 1804 to 1814. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) exercised a continuous control over the news that they would have to reach all his subjects, either through his marshals or his direct intervention [2]. Marshal Suchet (1770-1826) was entrusted with the supervision of the different gazettes of Seville, Joaquín Murat (1767-1815), Duke of Berg, those of Madrid[3].

The power of propaganda and information was vital, it is said that for Bonaparte gazettes and newspapers were equivalent to an army of 3000 men [4]. Between 1807 and 1808 European newspapers such as Journal de L’ Empire [5] or The Gazeta de Lisboa echoed throughout Europe. That is why some countries established sanitary cordons, such as the one carried out in Spain through the Royal Resolution of February 24, 1791[6], during the Secretary of State of Floridablanca, which occurred between 1777 and 1792. Napoleon already had a long propagandistic training , which facilitated its tasks of censorship and dissemination. In the Egyptian campaign of 1798 he published in Arabic and French bulletins, and harangues, for his soldiers and local populations, a strategy that he had already practiced in Italy. On franc soil, since 1799, the Corsican established Le Moniteur as the favorite newspaper of the French State. This and three others[7] were the newspapers in charge of transmitting his imperial figure from 1804 and onwards. And of course, their printing presses were the ones that the yoke of censorship weighed the least.

The French emperor used to oppose[8] the publication of certain topics such as:realistic claims[9], suicides, some murders, the movement of troops land and sea, the defeat of their armies, etc.

The press in Spain

The European and Spanish press followed an international scheme in its composition. In the European newspapers we found a first section dealing with global aspects or past events, after this a section dedicated to certain countries and their national politics. They concluded the weekly with a list of local businesses and public events. As a curiosity we point out that, in the header or in its final part, the method to access the newspaper was indicated together with the weather, being by irregular payment or subscription. This structure was the one followed by the Gazeta de Valencia , the Gazeta de Sevilla , El Diario de Barcelona or the Diario de Madrid [10] founded in 1758.

From Bayonne to Cádiz:bulletins, newspapers and gazettes

Although the law and the measures taken by the Central Supreme Board and its opposite, the government of José Bonaparte (1768-1844) through the Council of Castile , they did not exercise all the weight they should have, it is really interesting to analyze the different measures that they promulgated through the Cádiz Constitution of 1812[11] and the Bayonne Statute of 1808[12] on the freedom of the press and the exercise of the censorship. Submission to one legislation or another, and the prior civil conflict between Josefins and Fernandists, could define citizens as traitors or defenders of the country[13].

Article 45 of the Statute of Bayonne indicated “A board of five senators, appointed by the Senate itself, will have the task of ensuring freedom of the press”. A posteriori in 1812, the Cadiz constitution stated in its article 371 "All Spaniards have the freedom to write, print and publish their political ideas without the need for a license, review or approval prior to publication, under the restrictions and responsibility established by law. ”. It almost seemed that one document was trying to make up for the shortcomings of the other.

We found here two models of freedom of the press. The “Pepa” , named after Saint Joseph's Day[14], did not require a meeting or prior approval in the various publications, unlike the Bayonne Statute. This was so because the French code that had been established was a transitional document[15], pending continuous long-term evolution until the Josephine institutions were finally established, a fact that the government of José Bonaparte hoped would happen in 1813. The most curious thing is that despite its limited performance, the code of 1808 shows us a possible predecessor to habeas corpus [16] current in its article 46:

Ferdinand VII in search of imperial approval

In the “Diario de Madrid” from March 22, 1808[17] to April 10 of the same year, from Valençay , the submission of the Bourbons to the Bonapartes was reflected. We highlight the issue of March 22, 1808, where we see a proclamation by the Spanish monarch addressed to his people. It indicated the submission and support that should be offered to the occupying troops. On March 31, 1808 and April 9 of the same newspaper, we witness the royal decrees that ordered the delivery of basic necessities and blankets in the town halls. All these measures as a whole, and the subsequent departure of the royal family from the Palacio de Oriente[18], caused the terrible May 2, 1808. In this regard, the reflection of May 2 and 3 in the press is interesting. On the 4th of the same month, the Madrid newspaper published the measures taken by Murat's military government on the 2nd, all of them, by the way, supported by the exiled suitor.

May 2 meant a setback[20] in the freedom of the peninsular press, the death penalty and executions were on the minds of the Spanish, and of course, the advances that the imperials intended to bring were overlooked and ignored in all their aspects.

Currently we are still wondering how King José's Madrid would have come to be. The purge of the population of Josephine, the “Frenchified” , had a criminal character. Artisans, urban policemen, nobles and mayordomos had to leave Spanish soil and go to France, those who decided to stay by their own decision or because they had not had the opportunity to escape, did not receive a better fate as many ended up executed or imprisoned. From the labels, ink and blood his memory lives on today.

Notes

[1] From 1792 Austria, Prussia and the United Kingdom fostered different coalitions, facing the Convention (1792-1795), the Directory (1795-1799), the Consulate (1799 -1802) and the Empire (1804-1814). Prior to 1808, there would have been four coalitions on the following dates:1792-1797, 1798-1801, 1803-1806 and 1806-1807. Fremont-Barnes (ed), 2006, p. 23-39.

[2] The use of police divisions on French soil by Joseph Fouché (1759-1820), minister of police, who sent Bonaparte weekly reports is remarkable . In addition to all this, an excellent espionage service could be pointed out that reported directly to the emperor, owners of bulletins and gazettes such as Pablo de Husson were not aware of the control to which they were subjected. Pizarroso, A. (2007). “Press and war propaganda 1808-1814”. 18th notebooks , (8), p. 203-222.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid

[5] Founded in 1789, it would also be known by the name of Journal des débats . In 1804 Napoleon ordered the name change, it remained so until the government of Louis XVIII (1755-1824). Available at:https://gallica.bnf.fr/accueil/es/content/accueil-es?mode=desktop

[6] José Moñino y Redondo (1728-1808), Count of Floridablanca, tried to avoid possible external influences. He exercised a strong censorship in the peninsular press in addition to prohibiting several encyclopedias and illustrated volumes as a result of the French Revolution. See the Royal Academy of History:http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/9722/jose-monino-y-redondo

[7] Le Journal del Paris, Le Journal de l’Empire and The Gazette de France . Pizarroso, A. (2007). “Press and war propaganda 1808-1814”. 18th notebooks , (8), p. 203-222.

[8] Checa, A. (2013). “The Napoleonic press in Spain (1808-1814). A perspective”. The Spanish Argonaut , (10), p. 1-25.

[9] In reference to the population and mutineers favorable to the House of Bourbon as pretenders to the throne.

[10] According to historians Alejandro Pizarroso (2007) and Gérard Dufour (2004):its great competitor turned out to be La Gaceta de Madrid . One of the topics dealt with to a lesser extent is the subsistence of these newspapers and gazettes. In order to maintain their publications and cover their expenses, Antonio Checa (2013) has calculated that they should reach at least 150 subscribers.

Czech, A. (2013). “The Napoleonic press in Spain (1808-1814)”. A perspective. The Spanish Argonaut , (10), p. 1- 25.

[11] See at:http://www.congreso.es/constitucion/ficheros/historicas/cons_1812.pdf

[12] See at:https://www2.uned.es/dpto- Derecho-politico/c08.pdf

[13]Fernández, R. (2006). "Notes on Bonapartist Propaganda:Proclamations and Gazeta de Santander (1809)". The Spanish Argonaut , (3), p. 1-10.

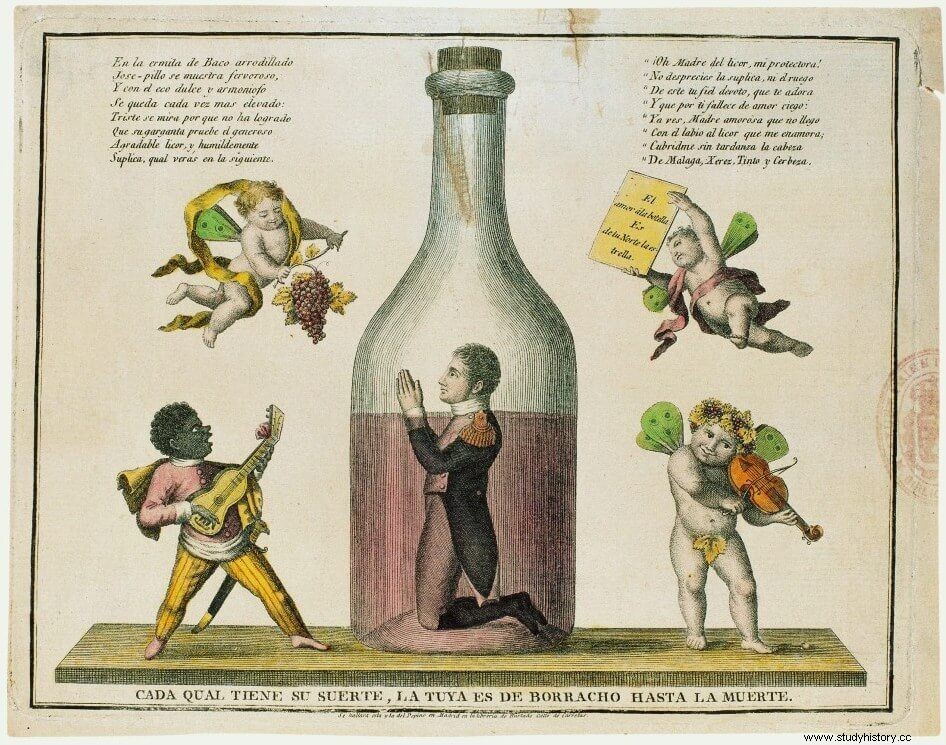

[14] March 19. King José, like Pepa, received a multitude of nicknames such as:Pepe Botella, Pepe Pepino, José Pepino, etc. See at:http://ceres.mcu.es/pages/ResultSearch?txtSimpleSearch=Caricatura%20de%20Jos%E9%20Bonaparte&simpleSearch=0&hipertextSearch=1&search=simpleSelection&MuseumsSearch=MHM%7C&MuseumsRolSearch=25&listaMuseos=%5BMuseo%20de%20Historia%20de% 20Madrid%5D

[15] In article 145 it states “Two years after this Constitution has been fully implemented, freedom of the press will be established. To organize it, a law made in the Cortes will be published.”

[16] Patricia, 2011, pp 4-10.

[17] (1807). (1808). Newspaper of Madrid. Spain madrid. Available in Memory of Madrid:http://www.memoriademadrid.es/buscador.php?accion=VerFicha&id=4603&pagina=9&tipodoc=docs_hijos&dia_inicio=&mes_inicio=&anio_inicio=&dia_final=&mes_final=&anio_final=

[18] «Indeed, the Corps Guards left very early, and at ten o'clock the Infanta María Luisa, former queen of Etruria, took the car to the Palace with her two sons, and the infante Don Francisco, his brother, and left. […] The Infante Don Antonio went down to say goodbye to the other Infantes on the stairs, and those who happened to be next to the Palace at the time swirl around and begin to shout that the French were taking the Infante Don Antonio, and They charge a French aide-de-camp who saved his life with a horse's claw." (Perez, 2008, p. 94.)

[19] General Agustín Daniel Belliard (1769-1832) originally from north of La Rochelle, was Murat's lieutenant in his staff and held the post from April 1808 military governor over the city of Madrid. Fremont-Barnes (Ed.), 2006, p. 595-596.

[20] Arco, 1916, p. 212.

[21] Pérez, 2008, p. 106.

Bibliography

Primary sources:

- Perez, R. (2008). Madrid in 1808, Story of an actor . Madrid:Historical Library.

- Rújula, P. (2012). Memoirs of Marshal Suchet, about his campaigns in Spain 1808-1814 . Zaragoza:Ferdinand the Catholic Institute (C.S.I.C.).

– (1807). (1808). Newspaper of Madrid. Spain madrid. Available in Memory of Madrid:http://www.memoriademadrid.es/buscador.php?accion=VerFicha&id=4603&pagina=9&tipodoc=docs_hijos&dia_inicio=&mes_inicio=&anio_inicio=&dia_final=&mes_final=&anio_final=

– (1808). June 28th. Lisbon Gazette. Portugal Lisbon. Available at HathiTrust's digital library:https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101080468729;view=1up;seq=625

– (1808). June 30th. Lisbon Gazette. Portugal Lisbon. Available at HathiTrust's digital library:https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101080468729;view=1up;seq=625

– (1808). February 5th. Lisbon Gazette. Portugal Lisbon. Available at HathiTrust's digital library:https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101080468729;view=1up;seq=625

– (1815). Moniteur Universel. Paris:Madame Veuve Agasse Imprimeur-Libraire. Available at:https://archive.org/details/lemoniteuruniver18151819pari/page/n3

– (1807). October 25. Journal de L’Empire. France:Paris Available at:https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797692j/date

– (1807). 30th of October. Journal de L’Empire. France:Paris Available at:https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797692j/date

– (1807). November 6th. Journal de L’Empire. France:Paris Available at:https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797692j/date

– (1807). November 24.Journal de L’Empire. France:Paris Available at:https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32797692j/date

Thematic books and encyclopedias:

- Arch, L. (1916). The periodical press in Spain during the War of Independence, 1808-1814 . Castellón:Joaquín Barberá Typography.

- Barbastro, L. (1993). The afrancesados:first political emigration of the Spanish 19th century (1813-1820) . Alicante:Juan Gil Albert Institute of Culture.

- Fremont-Barnes, G. (Ed.). (2006). The encyclopedia of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, A Political, Social, and Military History . Santa Barbara:ABC-CLIO.

- Ibarra and Rodriguez, E. (1941). History of the world in the Modern Age, Napoleon. Barcelona:Editorial Ramón Sopena, S.A.

- Lopez, J. (2007). The famous traitors. The Frenchified during the crisis of the Old Regime (1808-1833). Madrid:New Library.

- Sorando, L. (2018). The Spanish Army of Joseph Napoleon (1808-1813) . Madrid:Wake up Ferro.

Articles and magazines:

- Bar, A. (2013). “The Constitution of 1812:Revolution and tradition”, Spanish Magazine of the Consultative Function , Monographic Bicentennial of the Constitution of 1812, (19), 41-82.

- Czech, A. (2013). “The Napoleonic press in Spain (1808 -1814). A perspective”. The Spanish Argonaut , (10), p. 1-25.

- Dufour, G. (2004). "Les autorités françaises et la Gazeta de Madrid à l'aube de la Guerre d'Indépendance". The Spanish Argonaut , (1), p. 1-7.

- Fernández, R. (2006). "Notes on Bonapartist Propaganda:Proclamations and Gazeta de Santander (1809)". The Spanish Argonaut , (3), p. 1- 10.

- Moreno, A. (2012). "The Frenchified Gazette of Seville". The Spanish Argonaut, (9), p. 1-20.

- Pizarroso, A. (2007). “Press and war propaganda 1808-1814”. 18th notebooks , (8), p. 203-222.

- Piquerez, A. (2009). “The intrusive king and the Gazeta de Madrid:the construction of a myth, 1808-1810” The Spanish Argonaut , (6), p. 1-22.