On November 6, 1860, a wave of Stupor spread throughout the American states, especially those south of the Mason-Dixon line[1]. Abraham Lincoln, candidate of the very recent Republican Party, had been elected president! Considered by many citizens of the South an anti-slavery revolutionary willing to destroy their institutions and their ways of life, they soon began to crystallize the separatist ideas that had long been part of American political life. If the states had freely associated, then they should have freely been able to secede from the Union. Of course, this was not the idea that the president-elect had, much more favorable to the primacy of the federal State over each of the states that formed it, but there were still months left before he would take office.

Texas secession

On December 20, South Carolina declared its secession from the United States and under the impassive gaze of James Buchanan, acting president, other states would soon follow[2]. One of them was Texas, where the agitation had begun as soon as the victory of the Republican candidate was known. One of the first manifestations of Texan secessionism was the appearance of the Lone Star flag, the old insignia of the Republic of Texas ,[3] instead of the United States Stars and Stripes. Soon a series of bombings and riots, cleverly exploited by the secessionist press, and fears that Lincoln, once in office, would stir up the slave population to rise up against their masters, turned concern into hysteria and Texans. , who in 1859 had elected Sam Houston governor , hero of the war of independence, with a clearly unionist program, began to opt for secession.

However, old Houston, who was then sixty-seven years old but had not lost an iota of his combative character, refused to give in to secessionist pressure, since he was well aware that this was a path that would lead to war and defeat. According to Texas law, convening the legislature so that it in turn called a convention to evaluate and possibly declare secession was the prerogative of the governor, and despite the fact that there were more and more voices demanding the convocation and the isolation politician to which the living forces of the state were subjecting him, Houston, hoping that things would eventually calm down, did nothing. It was a mistake. On November 21, 1860, George M. Flournoy, state attorney general, Oran Milo Roberts, chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court, and John Salmon "Rip" Ford, politician, publisher, and former ranger ,[4] among others, they called on their own and without authority a state convention for January 28, 1861 to decide the fate of Texas. On December 17, Houston reacted. Aware that perhaps he had been mistaken in his dilatory attitude, he called a special session of the legislature for January 21. The idea was that the cameras declared the nullity of the convention that was to be held a week later, but the move backfired and they supported it. Defeated, the hero of independence was a silent witness to how events accelerated. On February 1, after four days of deliberations, the convention approved secession by 167 votes against 7, and called a referendum for the 22nd where only 18 of the 122 [5] counties in which the state was divided voted to remain in the Union . All of them were located on the northern and western borders, where the military posts of the federal Army had been protecting the population from Indian incursions for years.

The next step was to declare independence, which was became effective on March 2, and that all political officials take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy . Houston refused. “I will follow the ‘Lone Star’ with the same conviction as of old”[6], he is said to have announced, but also that he would resign his post before “yielding to usurpation and degradation.”[7] The swearing-ins were held on March 16 “Houston remained in his office on the ground floor of the capitol, carving a piece of pine, while a crowd gathered upstairs to attend the swearing-in ceremony. Three times the president spoke the name of Houston. Failing to appear, the convention declared his seat vacant and appointed Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark as the new governor.”[8] After announcing that he, despite everything, was still willing to fight for Texas if called upon (not for the Confederacy), the aged hero retired to private life. He would die on July 26, 1863, a few weeks after the South's defeat at Gettysburg [9] and Vicksburg [10], as he began to fulfill his prophecy of defeat.

The occupation of the state

While these political events were taking place, the newly independent Texas had to grapple with a vital issue, the presence of 165 officers and 2,558 soldiers in the military posts defending the state's borders. professionals belonging to the 1st, 3rd and 8th Infantry Regiments, 2nd Cavalry Regiment[11] and 1st er Artillery Regiment of the regular Army of the United States.[12]

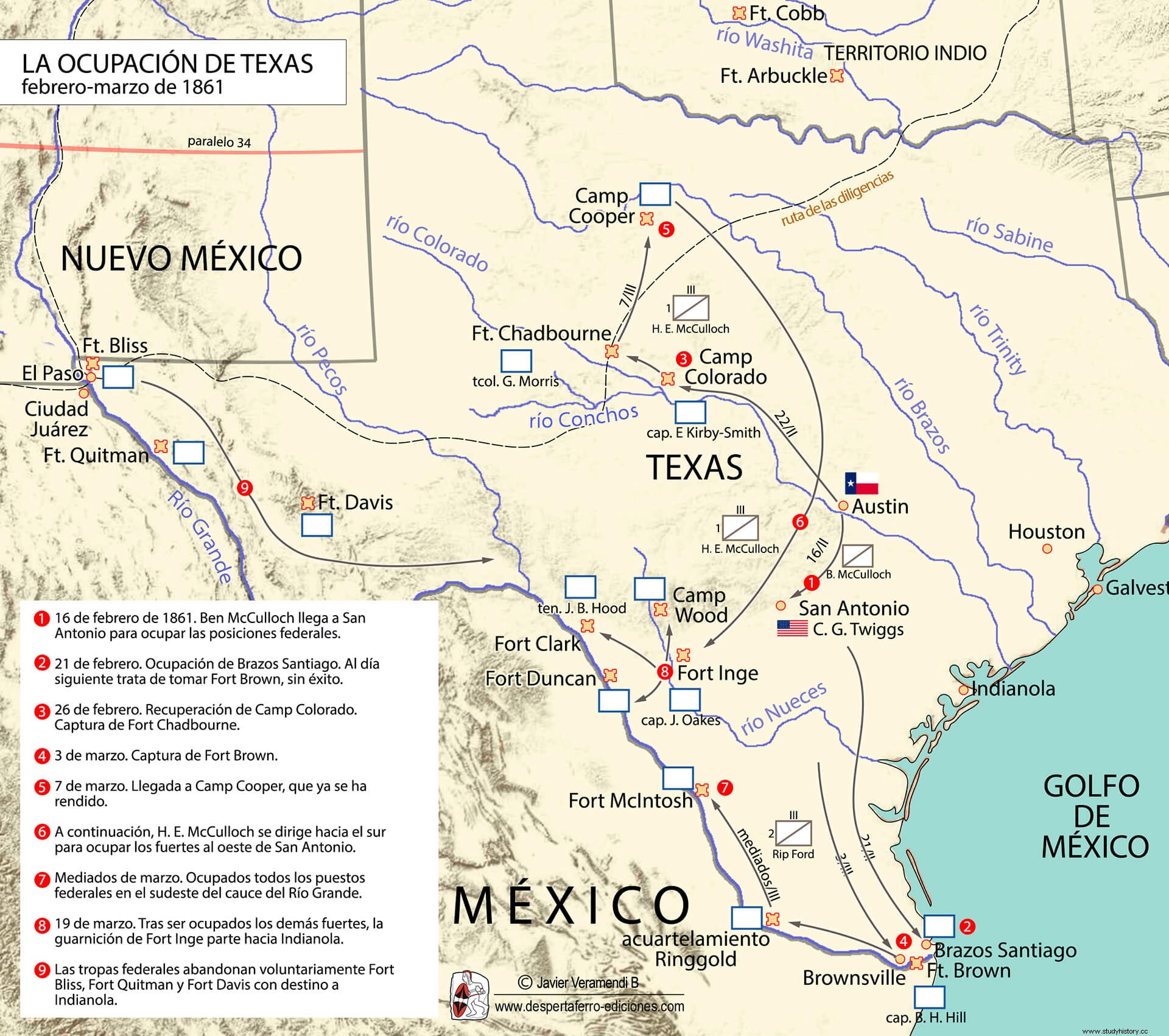

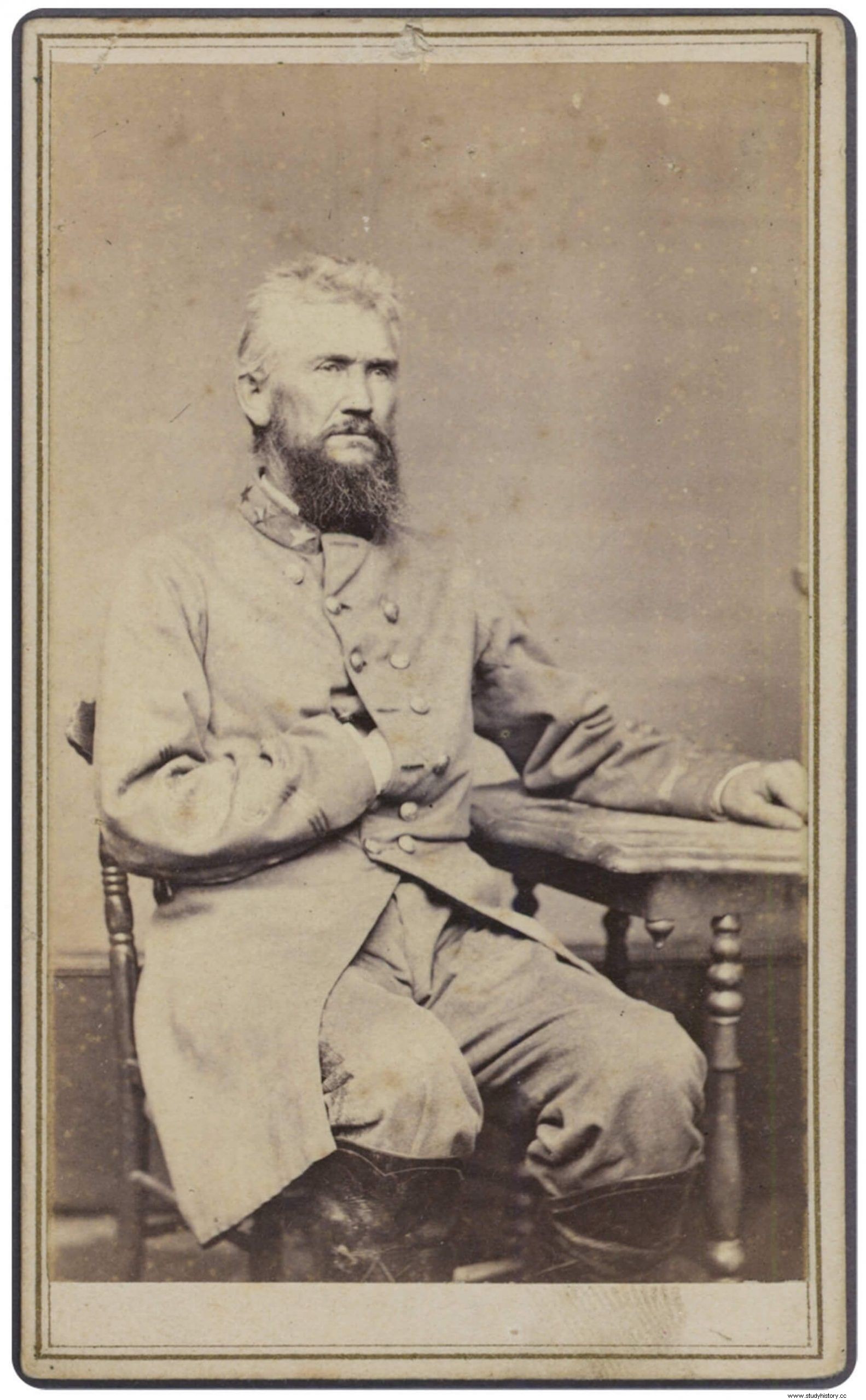

To do this, on February 2, 1861, just after secession had been approved and even before it was ratified in a referendum, the convention met in secret session to appoint a Committee of Public Security[13] whose function should be to take control of all federal properties in the State . Its members included brothers Benjamin and Henry Eustace McCulloch and John Rip Ford, who received colonel appointments and orders to raise a Texan army. Soon they would be joined by some federal Army officers who had resigned their posts to return to their home states.

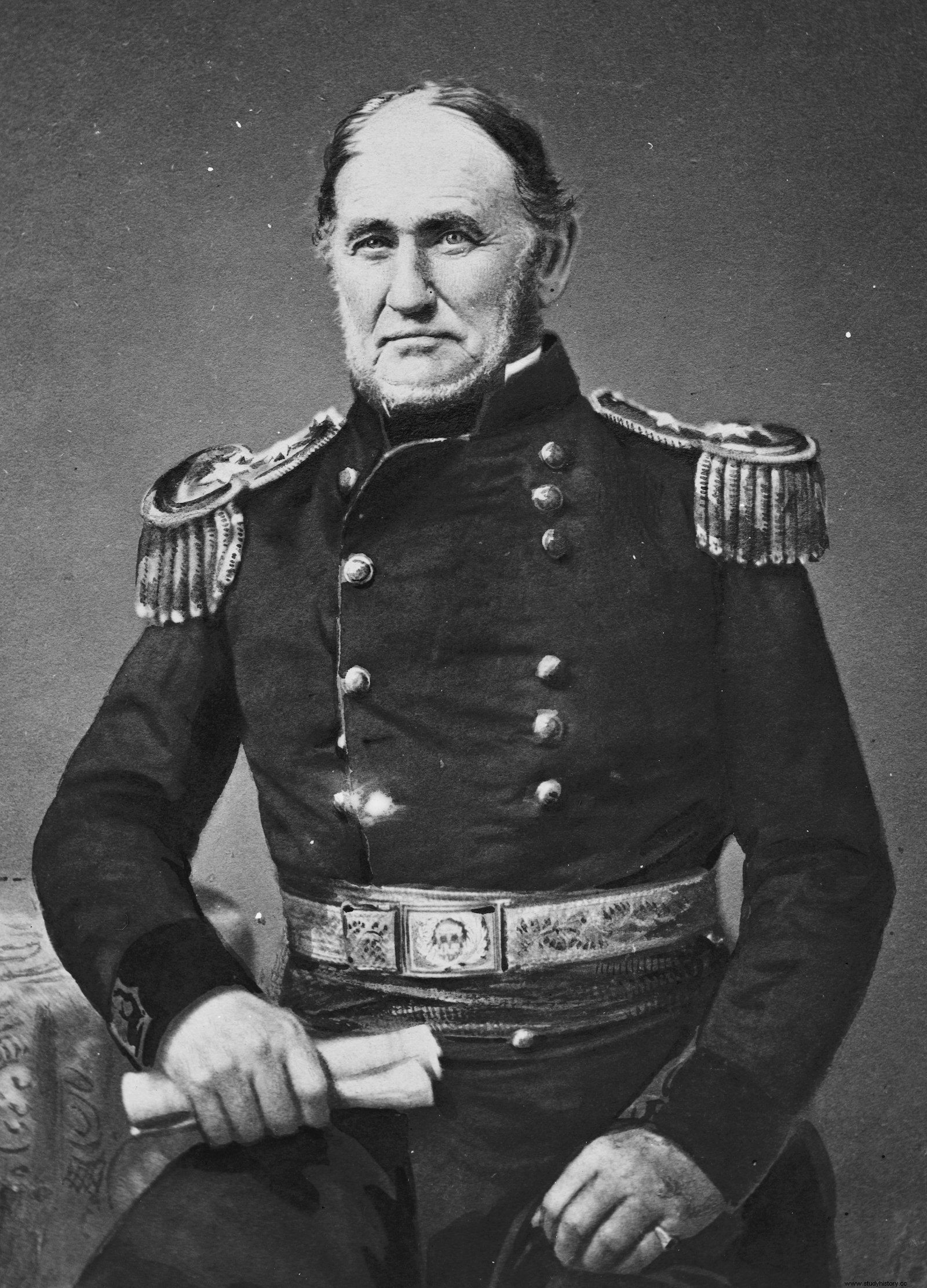

The takeover of federal properties of interest The military in Texas relied heavily on decisions made by General David Emanuel Twiggs , Commander-in-Chief of the Department of Texas and fourth-ranking officer in the United States Army, who had found himself in a serious dilemma as soon as events began. On the one hand, his honor and his military obligations prevented him from simply giving up the military posts and warehouses that were under his command; on the other hand, his condition as a Georgian led him to sympathize with the rebellion, and therefore to deliver forts, weapons and supplies to the Texians. The only solution that had occurred to him, even before secession was declared, had been to resign.

But Washington was a long way off and he wasn't going to get an answer before the Committee of Public Safety sprang into action.

Faced with a difficult task with hardly any troops, aware that the militias they recruited could be, at most, a mediocre enemy to face the professional troops of the federal Army; and aware of Twiggs's desire to be relieved of command, the men of the Committee of Public Safety had to act quickly. If the federal government accepted the resignation of the old general his more than likely successor was Colonel Carlos A. Waite, an ardent unionist that he could order the troops to hold out or, almost as bad as that, decide to retreat into New Mexico destroying everything the Texans wanted to occupy in his path. Quickly, three commissioners were dispatched to San Antonio to negotiate with Twiggs, and shortly thereafter Colonel Benjamin McCulloch, newly appointed Confederate commander of the District of Texas, departed to take possession of the facilities and warehouses with the help of a volunteer force. /P>

The report written by Twiggs in San Antonio on February 19, 1861 tells us how the events unfolded:

The presence of such a large contingent to face the barely one hundred and sixty federal soldiers that were in the city finally convinced Twiggs, who had already stated, on January 23, in a letter to Colonel Samuel Cooper in Washington[17] that “since I do not believe that there is any authority that wishes to wage a civil war against Texas, after secession […] I will order that arms and property be turned over to your agents […] of the Governor of Texas], keeping the weapons in the possession of the troops.”[18] After the occupation of San Antonio an agreement was reached with Twiggs to order the surrender of all positions under his command, with the promise that the soldiers would be transferred north from the ports of Brazos Santiago[19] and Indianola.[20] Of course, it was not expected that this order would be obeyed by the commanders of all the detachments, so the new secessionist Government of Texas sent Henry Eustace McCulloch[21] and Rip Ford, with volunteer forces, to do the job. charge of the forts that garrisoned the border. The first would act in the northwest of the state while the second was in charge of the Rio Grande border.

Texas goes to war

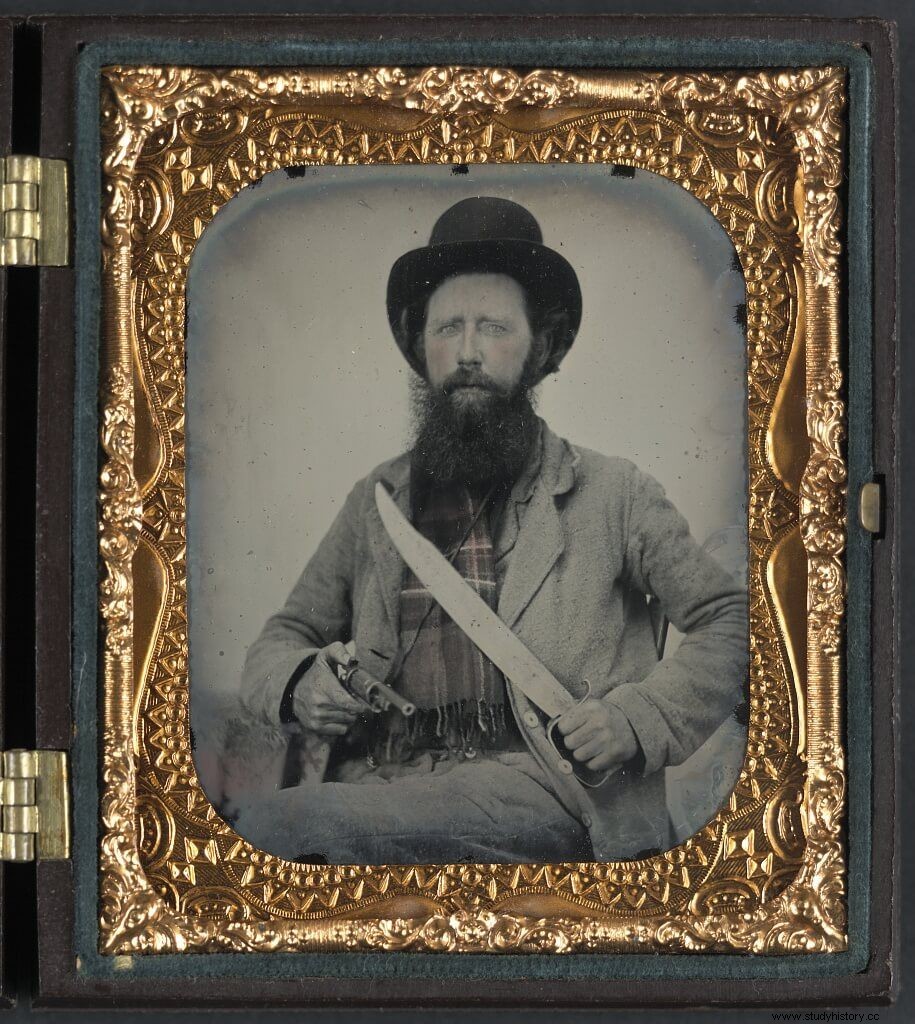

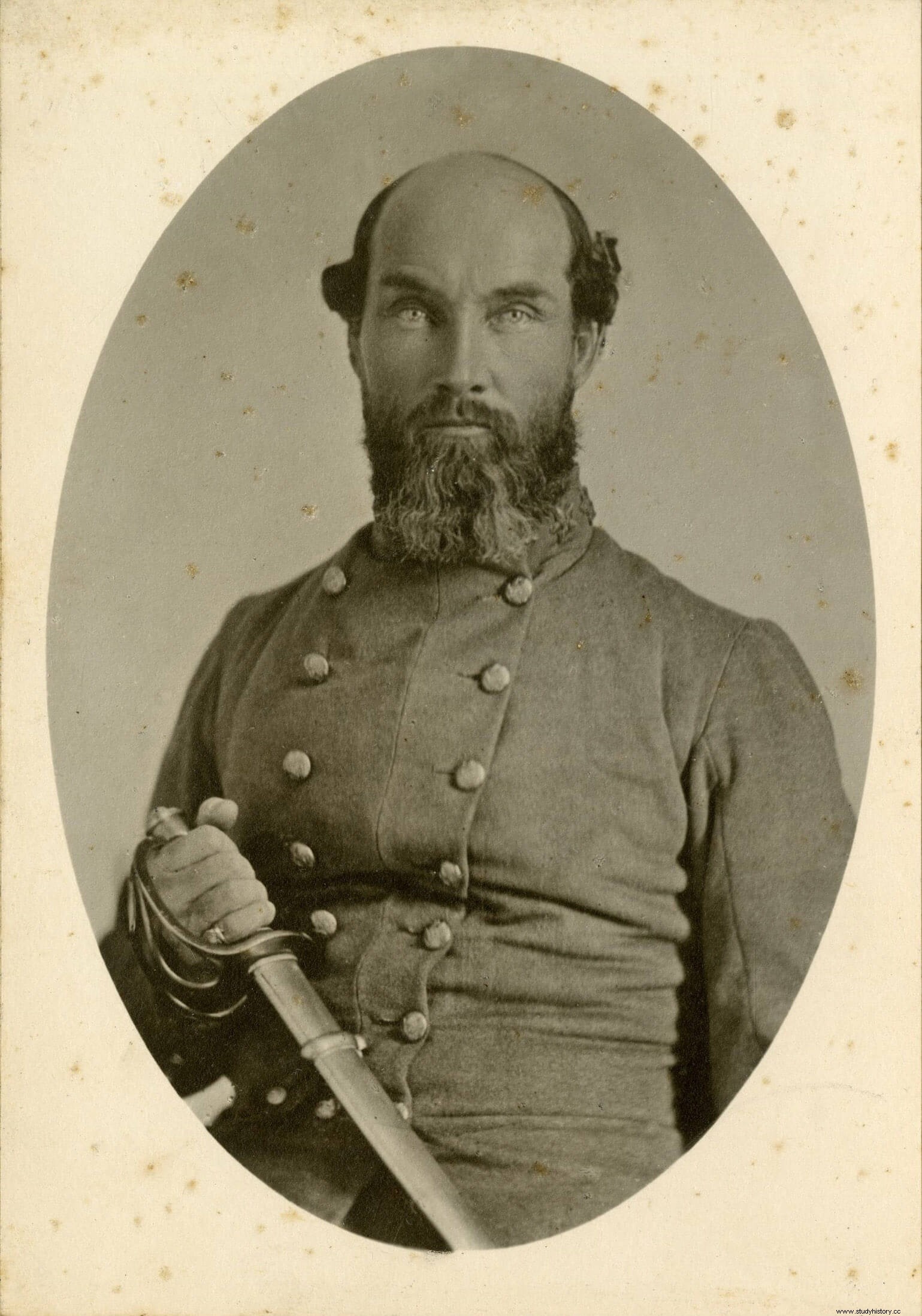

As soon as the first winds of secession blew in the state of Texas, John Robert Baylor, a character well known for his tough temper, forged over years of life on the frontier, and controversial for the brutal war he had carried out against the Indian tribes of the region, he published an advertisement in the newspapers in order to gather a thousand volunteers to go on a "buffalo hunting expedition". No one was fooled, and radio-macuto soon spread the word that Baylor intended to assault the federal positions in San Antonio first and conquer New Mexico later. His announcement did not have the desired success. Adventurers of all stripes, gunslingers and frontiersmen turned out without trade or benefit, but they never reached the desired number and soon had to be integrated into one of the more formally constituted units, specifically in Colonel Rip Ford's 2nd Mounted Rifle Regiment.[22]

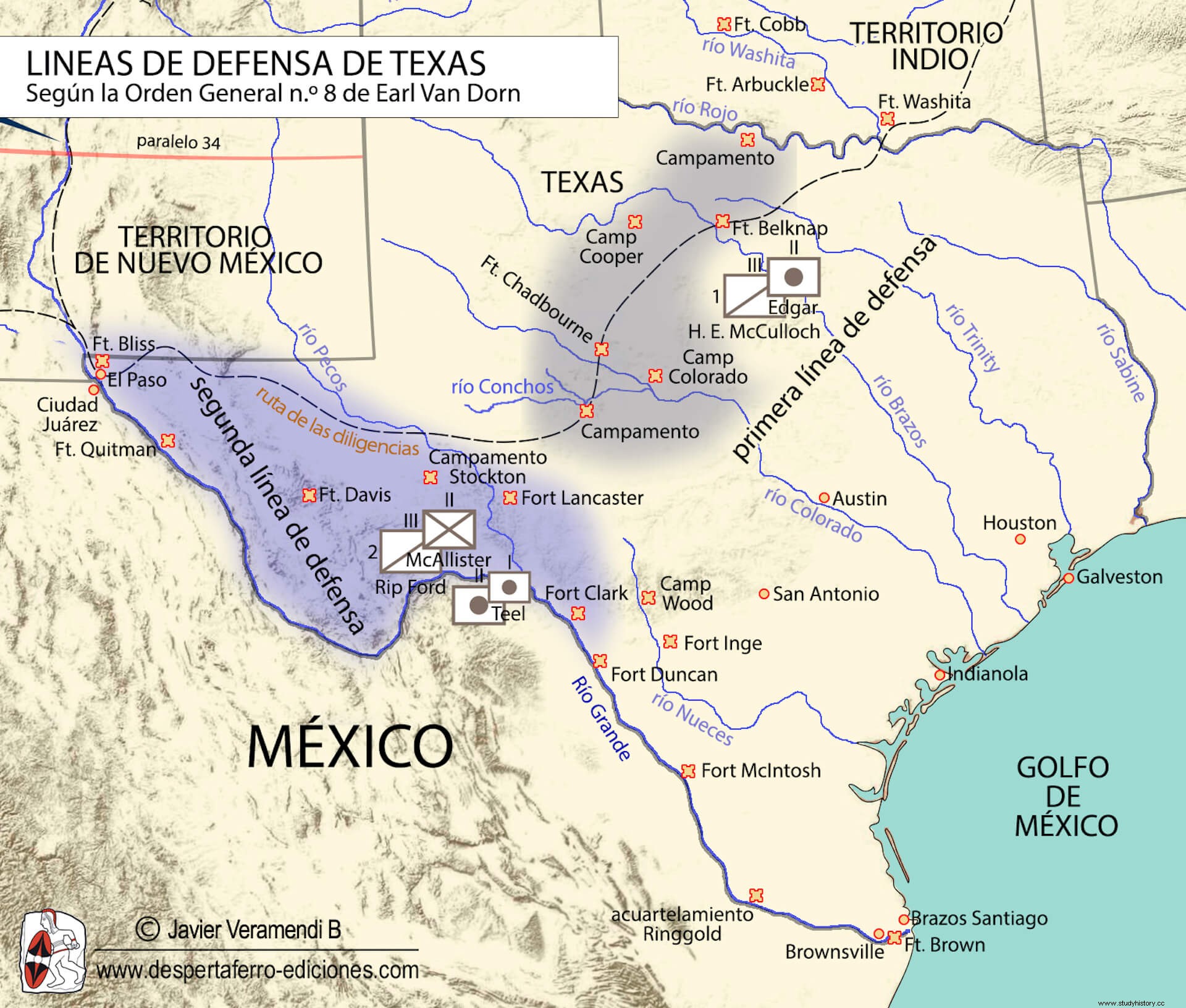

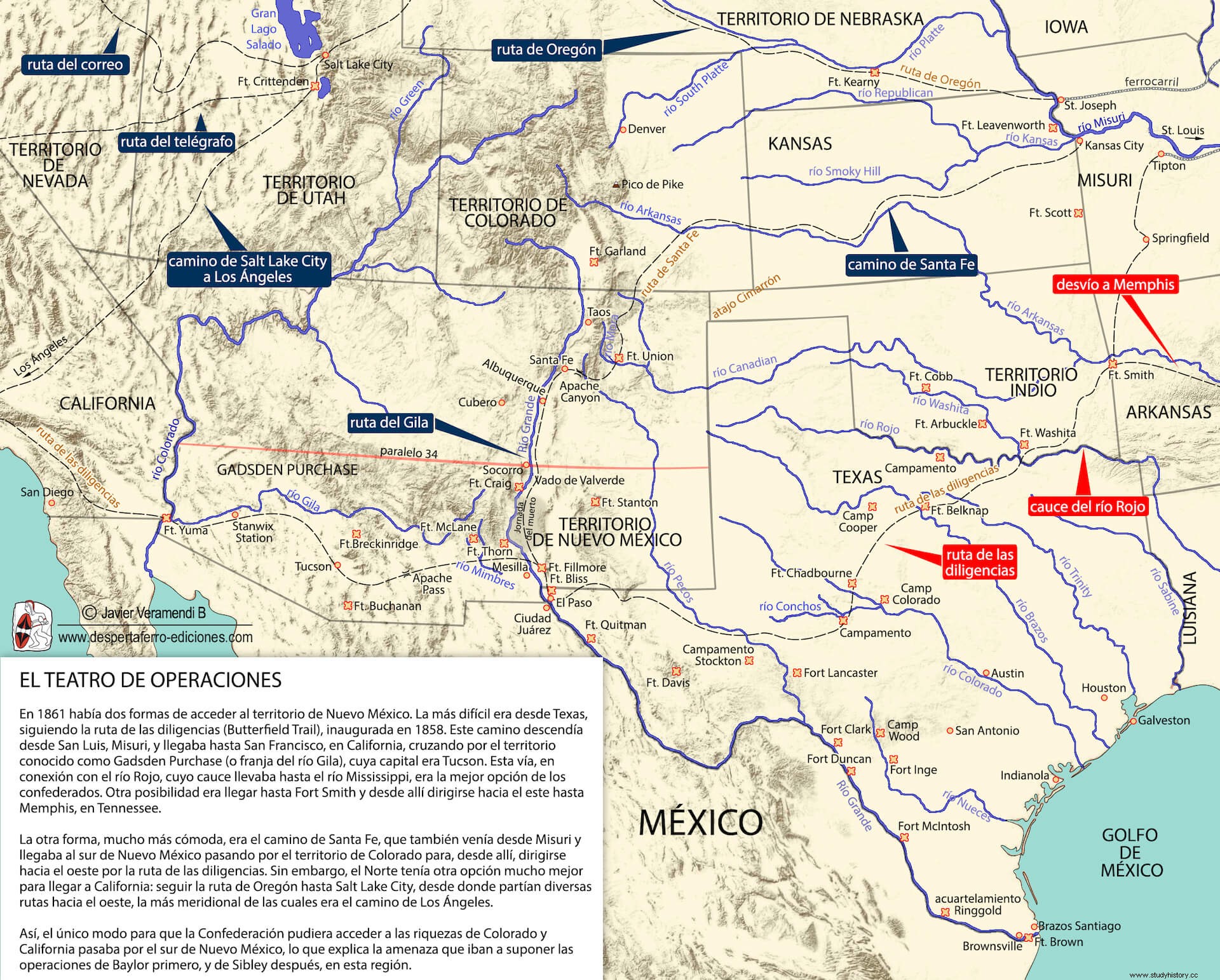

Meanwhile, Texas had sent delegates to Montgomery, Alabama , to participate in the constitution of the Confederate States of America on February 8, 1861, and on April 11, just the day before the bombardment of Fort Sumter started the war, the new Government sent a commander in chief to took charge of the Department of Texas, it was Colonel Earl Van Dorn [23]. This had several objectives. First, to consolidate the state militarily, and for that, he had to start by organizing the defense, and then he would take care of forming a Texian brigade to send to fight on the battlefields east of the Mississippi. Seeking success in the first of these missions, on May 24, 1861 he issued an order specifying that:

Point V of this same order indicated that, temporarily and until the arrival of Colonel Ford, the second line was under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Baylor, who was to “give the orders necessary for the dispatch of the companies currently in this vicinity [San Antonio] to the positions of the second line”[26]. Except for Fort Quitman, which would receive no garrison.

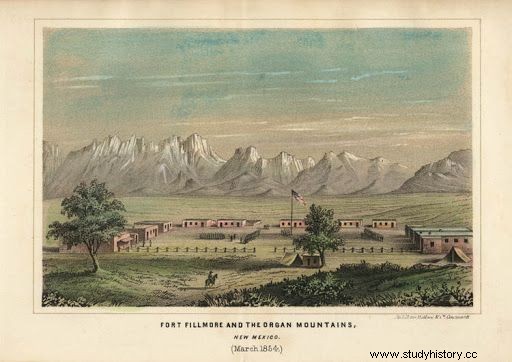

In compliance with these orders, Baylor traveled to Fort Bliss, in the extreme west of Texas, next to El Paso, where he arrived on July 15 with about three hundred troops from the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles, while Colonel Ford set up his command post in Brownsville, in the gulf coast. At the time, the virtually roadless 1,300 km separating the two officers made Baylor's command an independent force for all practical purposes, and he set out to exploit this independence by launching an offensive north, following the course of the Rio Grande into the present state of New Mexico . The reasons that prompted him to make this decision were basically two:the presence of a strong element of support for the Confederacy in the Mesilla Valley, a few kilometers north of the interstate border, and the growing accumulation of federal troops in Fort Fillmore , just south of Las Cruces, from where they threatened not only the Confederates in Mesilla but also the newly occupied Confederate positions around El Paso.

As far as the political scenario is concerned, it all started on March 16, 1861, the very day that Sam Houston refused to swear allegiance to the Confederacy, with the celebration in Mesilla of a convention of the people of Arizona[27] that ended up repudiating the federal government and declaring that all the territory of New Mexico south of the 34th parallel became Confederate territory .[28] From a military point of view, in a region where the population was sparse, dispersed, and largely of Hispanic origin, a few Anglo-Saxons gathering to make noise was something that Colonel Edward Richard did not worry too much about. Sprigg Canby, who had been appointed Federal Commander-in-Chief of the Department of New Mexico following the resignation of Colonel William Wing Loring to offer his services to the Confederacy.

To that end, he also requested that the dispatch to Kansas (and later to the eastern battlefields) of some of the regular troops still present in New Mexico be delayed. /p>

The invasion of Arizona

It was precisely the possibility, very real as can be deduced from the Canby letter cited above, that the federal government would send more troops south of the Rio Grande, the reason of convenience military wielded by Baylor to invade New Mexico.

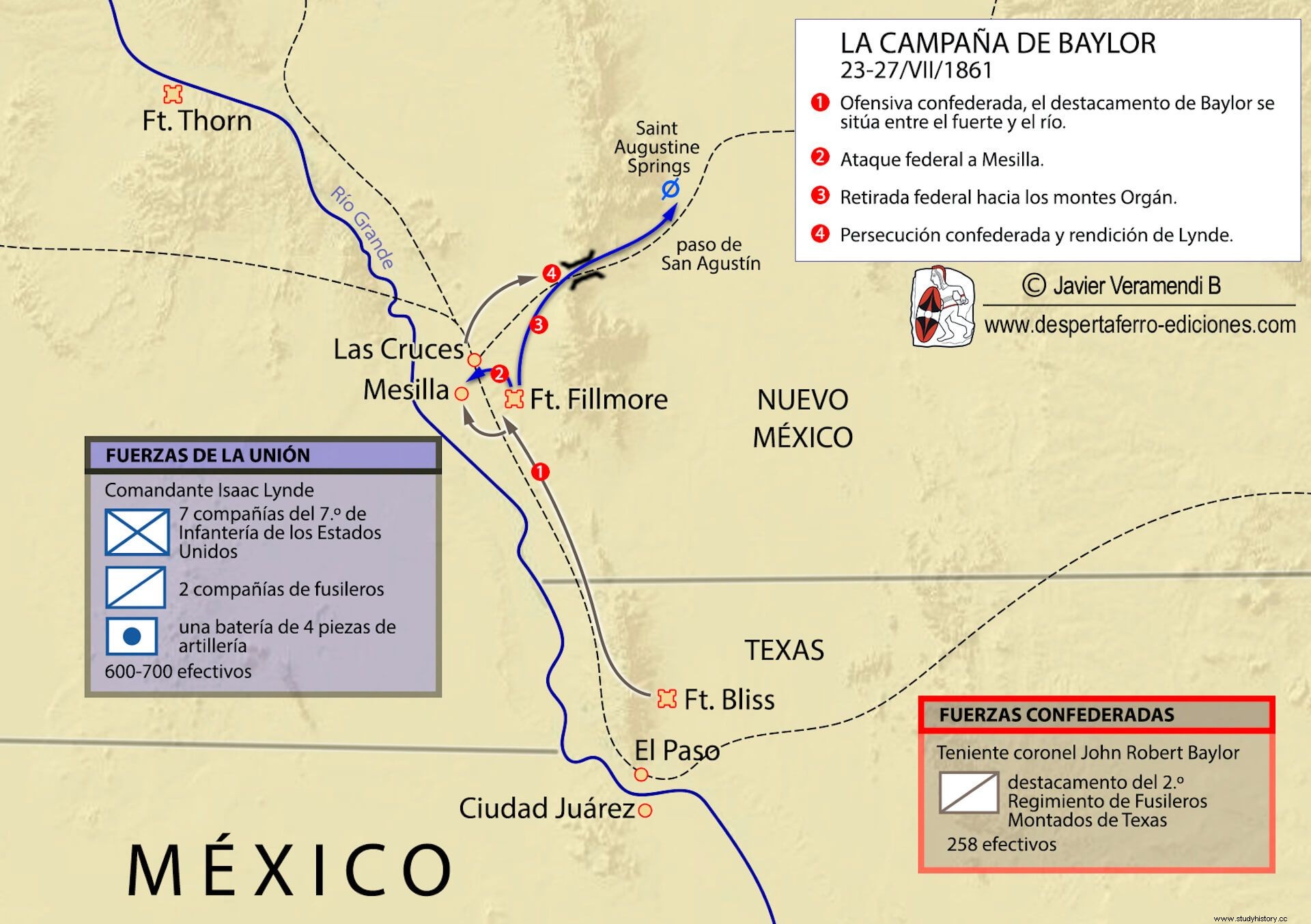

The Confederate plan was to surprise the 600-700 soldiers garrisoning the fort, which required two things:thorough reconnaissance and reaching the Unionists without being caught. detected. Baylor himself would indicate, in his report on the campaign, that both conditions were met:“[…] I sent a detachment, under the command of Commander Waller, to reconnoiter Fort Fillmore and find out what the positions of the enemy pickets were, as well as if it was possible to approach the fort without being discovered. Commander Waller's report gave me the satisfactory news that it was possible, during the night, to reach a position between the fort and the [Grande] river.”[31]

On the morning of July 23, 1861, a column of 258 men left Fort Bliss heading north. They were all militiamen, but these were not to be confused with farmers , office workers or other peaceful men who were joining ranks across the country. They were hardened men, some of them veterans of the wars against Mexico or against the Indians, Apaches or Navajos, who populated the region, others gunmen of all stripes. Many had signed up to “hunt buffalo” following Baylor's announcement months earlier, and almost all of them had come from the border counties of the Rio Grande or the lawless vastness of the western half of the state. They arrived at their destination on the night of July 24-25 without being detected, after surprising and capturing some of the prominent pickets precisely to warn of their arrival. Silently, Baylor spread out his force between Fort Fillmore and the river, intending to capture the enemy's cavalry as they were brought in to water early. He hoped that, when faced with no mounts for horsemen or draft animals for baggage, the commanding officer of the garrison would attack to recapture his cattle and access to water, thus losing the cover of the fort's defenses. Everything was ready “but the desertion of a soldier from the company of Captain T. F. Teel, who informed Major Lynde [in command of the fort] of our strength and our position”[32] ruined everything. Hearing the alarm beating of the federal drums, Baylor realized that his ruse had failed and decided to retreat to Mesilla.

Interestingly, the withdrawal had the effect that surprise had failed to provide. Seeing his enemy go, Major Isaac Lynde of the United States 7th Infantry Regiment, commanding the fort, decided to play Baylor's game and scrambled out of position with a column to hunt down and destroy to the Confederates . These, entrenched on the adobe houses of Mesilla and behind the stone wall of a large corral, saw how their enemies arrived and stopped to then send a group of men to request their unconditional surrender. But Baylor was in no mood to give in so quickly, especially since the enemy had finally broken out into the open, so his terse response would have been "let's fight a little first."[33] It was around 5:00 p.m. on July 25 when Lynde sent his men on the attack. First the artillery, to soften the enemy, then the infantry, in a skirmish line, who got stuck in the soft sand or among the tall cornfields, and finally the cavalry, who had no better fortune. The Confederates resisted and repelled all attempted assaults, until Lynde decided to retreat back to the fort.

This skirmish, which resulted in very few casualties – two Confederates and three to thirteen Unionists killed and an unknown but extremely low number wounded—it was to have unexpected results. Behind her, the concern made a dent in the unionist leader, who would later indicate that the enemy had received reinforcements:at least a hundred men and an artillery battery, and that his position was untenable. “He had previously reported – he justified himself in the report he wrote on August 7 – that the fort was indefensible against artillery because it had a semicircle of sandy hills around it that dominated its position, and that the only water supply was a stone's throw away. distance of about two kilometers.”[34] On July 26, convinced that if he remained in his position he would have to surrender, Lynde, whose strength was actually superior to his enemy's, decided to abandon Fort Fillmore But instead of trying to bypass the Confederate positions and go north up the Rio Grande Valley, he decided to march northeast through the desert and the Organ Mountains. His intention was to make a night march to reach Saint Augustine Springs, 32 km away, during the morning of the 27th. then march another 225 km north to reach Fort Stanton, in the territory of the Mescaleros Apaches. The night part of the trail went well.

The news had yet to get worse:“I took the decision to advance to the fountains with the mounted troops – he continues telling –, and return with water for those who were suffering in the rear […]. On reaching the springs, I found that the water supply was so meager that it would not be sufficient for my strength.”[36] Tiredness, lack of water and the feeling of defeat , coupled with the presence of a column of Confederate troops on his heels, forced Commander Lynde to make the most unpleasant of decisions, surrender. “The force under my command at the time of the surrender was ninety-five privates and non-commissioned officers and two officers. Regarding the infantry, I do not have the means to know the exact figure, but there were seven companies of the 7th Infantry, with eight officers present.”[37] In fact, everyone who had stayed behind or was part of the rear of the column had already been captured by the time Lynde surrendered. The Baylor report also gives a number of captured troops which, although erroneous as far as the number of companies is concerned, seems more in line, quantitatively speaking, with the original garrison at Fort Fillmore. “Major Lynde's force consisted of eight companies of infantry and four of cavalry, with four artillery pieces. All this amounted to almost seven hundred men.”[38] Following the customs of the time, in two days all of them would be released on parole.

This victory allowed the creation of the confederate state of Arizona in the southern half of New Mexico and part of present-day Arizona, causing the momentary withdrawal of federal forces to the north. Fort Stanton, the destination Lynde's column had been unable to reach, was abandoned in a fit of panic; only one garrison remained at Fort Craig, a post we'll talk about later. On the other side, Baylor was appointed governor of this new territory, Confederate ambition gained wings, and preparations for a new campaign soon began.

Notes

[1] Established between 1763 and 1767 to separate the states of Pennsylvania and Maryland, in the 19th century it was considered the line that separated North from South.

[2] After South Carolina, the states of Mississippi (January 9, 1861), Florida (January 10), Alabama (January 11), Georgia ( January 19), Louisiana (January 26), Texas (February 1) and much later and after the bombing of Fort Sumter on April 12 and 13, 1861, Virginia (April 17), Arkansas ( May 6), North Carolina (May 20), and Tennessee (June 8).

[3] That lasted from the independence of Mexico in 1836 until its incorporation into the United States in 1845.

[4] Cutrer, T. W. (2017):Theater of a Separate War. The Civil War West of the Mississippi River 1861-1865 . Chapel Hill:The University of North Carolina Press. p. 16.

[5] Of these, in eleven secession only obtained 60% of the votes.

[6] Cutrer, p. 17

[7] Ibid.

[8] Josephy, A.M. Jr. (1991):The Civil War in the American West . New York:Vintage Books. p. 22.

[9] July 1, 2 and 3, 1863. See Guelzo, A. C. (2020):Gettysburg . Madrid:Awake Ferro Editions.

[10] July 4, 1863, one day after Gettysburg.

[11] Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee until shortly before, who would be in transit to Washington during the secession of Texas.

[12] Josephy, p. 26.

[13] Made up of fifteen members, all with military experience, chaired by John C. Robertson, Smith County representative to the convention.

[14] he was 71 years old and would die the following year.

[15] Letter from General D. E. Twiggs to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, of the United States Army, dated San Antonio, Texas, on January 15, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 1, p. 581.

[16] Report by General D. E. Twiggs, United States Army, on the seizure of the United States Arsenal and Barracks at San Antonio, and the surrender of the posts military, etc., in the Department of Texas. February 19, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 1, p. 503.

[17] This is the same Samuel Cooper who would later become the military aide to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, but was still serving in the federal Army at the time.

[18] Letter from General D. E. Twiggs to Colonel S. Cooper, Adjutant General in Washington D.C. sent from San Antonio on January 23, 1861. War of the Rebellion , a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 1, p. 582.

[19] On the North American side of the mouth of the Rio Grande.

[20] On the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, halfway between Corpus Christi and Galveston.

[21] Brother of Ben McCulloch, whom we referred to earlier and who would lose his life on March 7, 1862 at the Battle of Pea Ridge, while Henry Eustace would survive the war.

[22] The 1st came under the command of Henry Eustace McCulloch.

[23] A veteran of the Mexican War, he had risen to the rank of militia general, but was a colonel in the Confederate Army. The duplication of ranks between the militias and the regular army makes it sometimes difficult to know the specific rank of each officer.

[24] The first line, which was to be oriented northwest, would extend from the Rojo River to the Conchos, while the second was to follow the course of the Rio Grande.

[25] General Order No. 8, issued by the General Headquarters of the Confederate troops in Texas, located in San Antonio, on May 24, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 1, p. 574.

[26] Ibid. p. 575.

[27] The Arizona of the time corresponded to the so-called Gadsen Purchase, in Spanish the Venta de la Mesilla, a strip of territory that extended west from Las Cruces to Tucson and Fort Yuma, in present-day Arizona, and which had been purchased by the US government from Mexico in 1854.

[28] Josephy, p. 40.

[29] Letter from Lieutenant Colonel Edward R. S. Canby, 10th Infantry Regiment, to the Assistant General of the US Army, at Army Headquarters in New York; written in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on June 11, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 1, p. 606.

[30] Report of Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor, commander of the Confederate States in Arizona, written in Doña Aña, Arizona, on September 21, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 4, p. 17.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] There are other versions of Baylor's answer:“We will fight first and surrender later”, or “if you want to take the town, come and do it”. All mentioned by Cutrer, p. 97 and no. 9

[34] Report by Major Isaac Lynde, 7th Infantry, written at Fort Craig, New Mexico, August 7, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 4, p. 5.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Report of Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor of September 21, 1861. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , series 1, volume 4, p. 19.