One of Sibley's advantages in their offensive against Fort Union it was that, having once supervised the construction of some of the complex's buildings, he was well acquainted with the layout of its defences; the other was that news had reached him that the eight hundred men stationed at the post were demoralized. However, what he didn't know was going to be a real problem. As the Confederates prepared their invasion of the Rio Grande, the westernmost departments of the United States Army had done their best to move some of their few troops into New Mexico. A column with the strength of a brigade, coming from California under the command of Colonel James H. Carleton, would leave for the east, but after the battle of Valverde and without time to help in this campaign.[1] The most effective help was going to come from the north, it was the 1. er Colonel John Potts Slough's Colorado Volunteer Regiment .

The men of Colorado

A heavy blizzard was falling on February 22, 1862, when the Colorados set out, and the weather was not going to give them a break. Even so, the route was carried out at a devilish pace in which the men had to cover kilometers and kilometers through a layer of snow of several centimeters, with hardly any breaks and only rations of biscuit to eat. They were still in southern Colorado on March 1, when news of Canby's defeat at Valverde Ford reached them,[2] and on March 8, while ascending Raton Pass, they learned that Sibley had already conquered Albuquerque and Santa Fe . So, against gale-force winds and bitter cold, the Coloradinos shed some of their gear and picked up the pace to reach Fort Union on the 11th, having traveled nearly 300 miles in just seventeen days.[3] For the eight hundred combatants who garrisoned this lonely but very important military post, there is no doubt that the arrival, "with drums beating and flags in the air",[4] of the "Pike's Peakers" regiment,[5] 1st of Colonel Slough's Colorado volunteers were a blessing. It was not so, however, for fellow Colonel Gabriel René Paul, commander in chief of the 4th New Mexico Volunteer Regiment, the fort and the Eastern New Mexico Military District. “After the arrival of the 1. er Regiment of Colorado Volunteers to Fort Union, I found that Colonel Paul of the 4th Regiment of New Mexico Volunteers had completed preliminary preparations for sending a column to the battlefield and, by seniority in the ranks of volunteers , I reclaimed command”[6], Slough coldly indicates in his report.

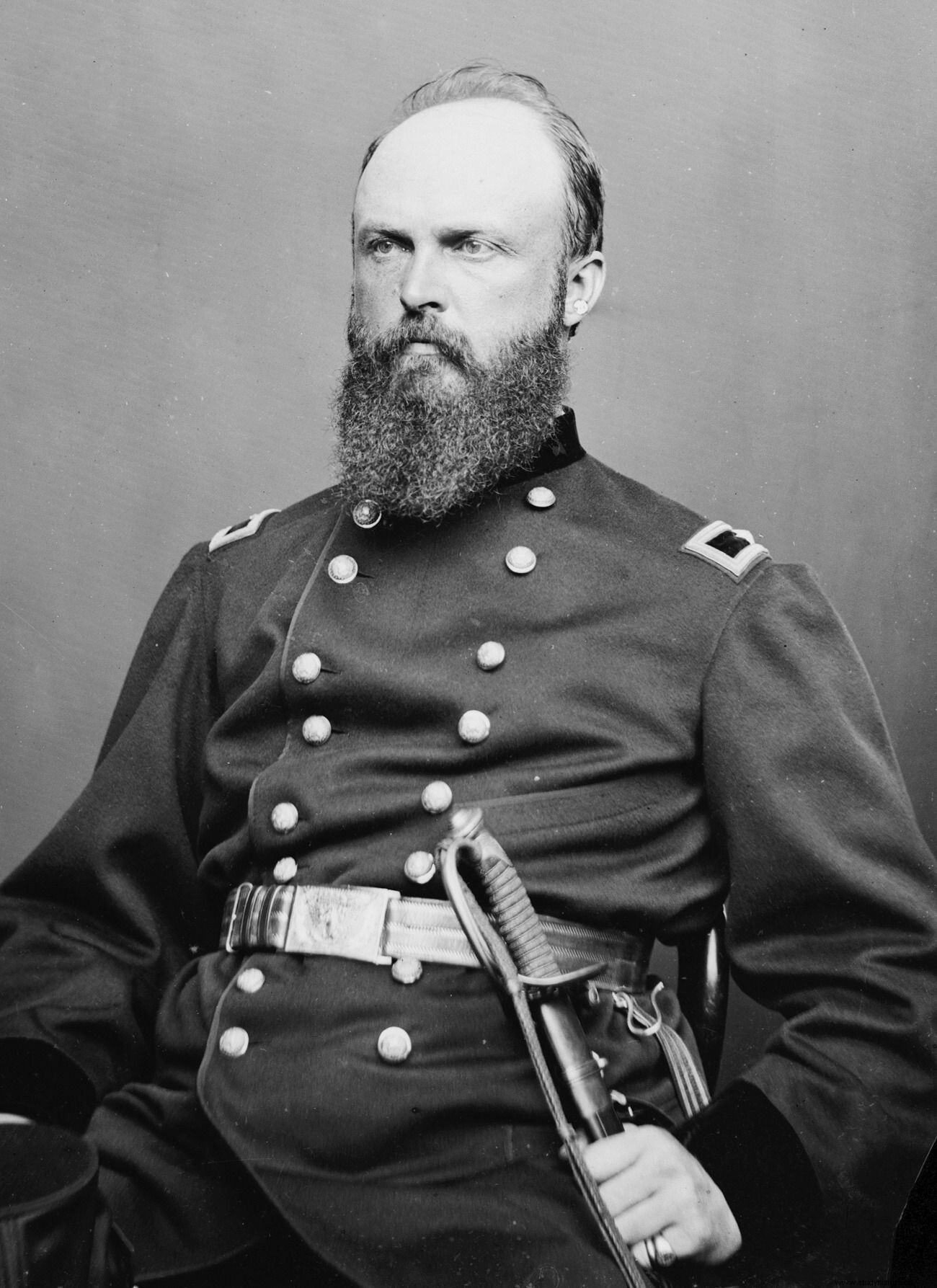

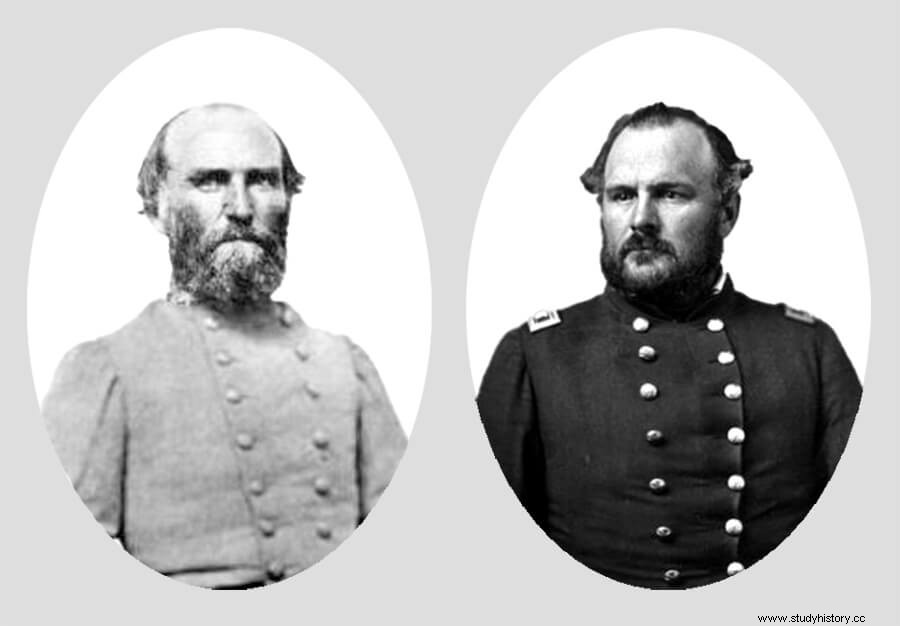

The new commanding officer, who was only 33 years old, had arrived in Denver, where he practiced as a lawyer, after being expelled from the Ohio legislature for a fist fight with a partner. Strictly disciplined, before leaving for the south he had been told that some of his men were conspiring to kill him, something that would not happen in the end. The bullet bearing his name was not to reach him until December 16, 1867, two years after the war, fired by a man he had grievously maligned. Paul, on the other hand, had graduated from West Point in 1834, was a career soldier and had combat experience as he had fought in the battle of Cerro Gordo and had participated in the assault on Chapultepec [7]; however, he had less seniority than his antagonist, so he had to relinquish command of force to a clearly less qualified officer. Aware of his situation and no doubt embittered, Paul relinquished command just before orders came from Canby, their superior, who was still at Fort Craig, for future operations. They specified that they “would not rely on the New Mexico troops, except for partisan actions, and that only when the main operations could not be affected”[8] and that they “concentrate all the trusted forces until the arrival of reinforcements from Kansas, Colorado and California”[9]. It also indicated his intention to depart from Fort Craig and that "I will indicate the route and meeting point [of both forces] verbally and through several messengers" [10].

As can be seen, Canby's orders indicated that Fort Union had to be defended and his instructions awaited for an eventual concentration of the forces of both posts, but Slough, already in charge, he was not willing to let time pass . For this reason, in a letter dated the 22nd, Paul insisted on the order to wait and added:

Slough sent his reply, negative, to through Captain Gurden Chapin, 7th Infantry, in his capacity as acting aide. “On behalf of the commander of the Department and in the best interest of the service [Paul would insist one last time on the 22nd] and the safety of all troops in this territory, I protest against this movement of yours , carried out two days before the agreed date and that I consider a direct disobedience to the orders of Colonel Canby.”[12] This time Slough didn't reply. As far as he was concerned, the die was cast.

For their part, the Confederates had also distributed their forces. Davidson, an exceptional witness to the events, although he often gets the dates wrong, indicated in his memoirs the disposition of Sibley's troops and their dispatch to Fort Union, under the command of Major Pyron of Sibley's battalion, the Companies A, B, C, and D of the 5th Texas Mounted Rifle Regiment under Major Shropshire and Phillips' company—the Santa Fe Gamblers also known as Phillips's Bandoleros. This force arrived at Johnson's Ranch on March 25. The crucial act of the campaign was about to begin.

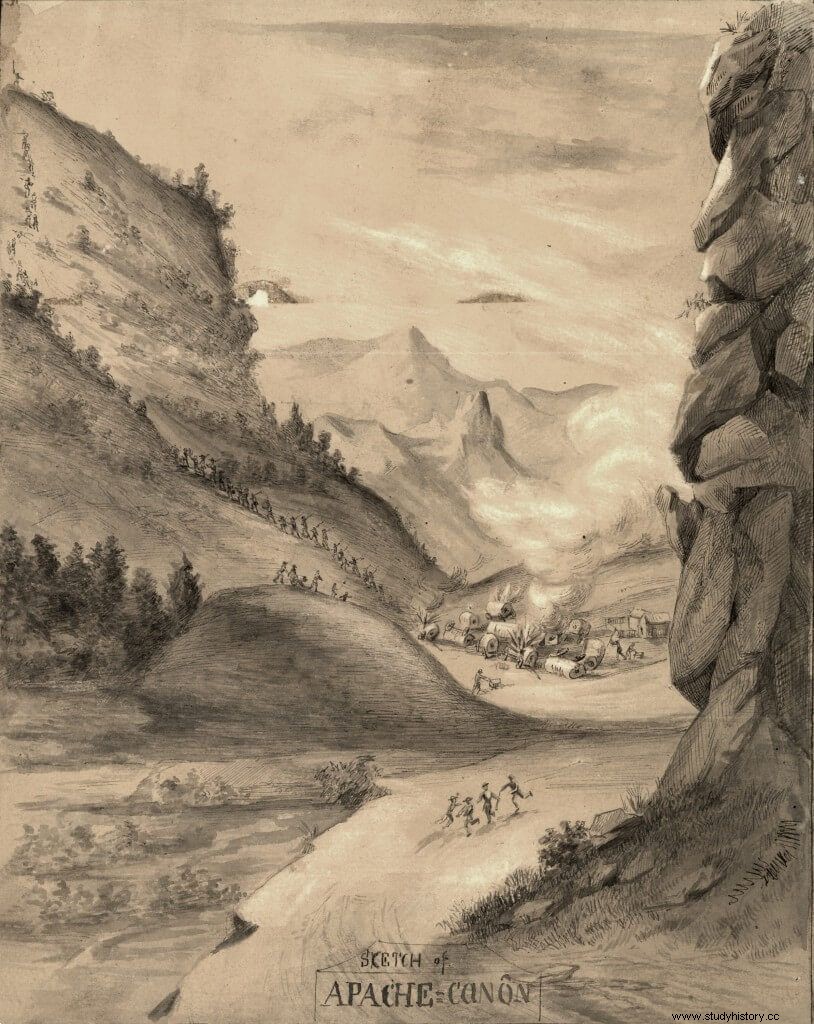

Apache Canyon Showdown

It was around 3:00 p.m. on that same March 25 when Major John M. Chivington left Bernal Springs at the head of 418 men, among whom were infantry troops from the 1. st Colorado Volunteer Regiment, some elements of the 1st er and 3rd Regular Cavalry Regiments and Company F, Cavalry, of the 1st er Regiment of Volunteers of Colorado,[13] and they marched until midnight, at which time, knowing the proximity of the enemy, they camped to rest for a few hours. Despite the controversy with Colonel Paul and against Canby's orders, Slough had decided to advance on Santa Fe.

The Apache Canyon Battle it took place at the west exit of the pass, not far from the Confederate camp, when the Union column ran into the vanguard of Pyron's men, whose total strength numbered about 350. The first movement was carried out by a federal cavalry force of about twenty men, commanded by Lieutenant Nelson, who entered the pass on foot when it was only 2:00 a.m. and, after a long and silent night maneuver, captured to enemy pickets. By this time it was 10:00 and the bulk of Chivington was making progress towards the gorge. "The detachment got back on the move and just as we entered the (Apache) canyon we discovered the vanguard of the enemy."[14] The Confederates planted their guns in the middle of the road and forced the Unionists to dig in, but the commanding officer soon sent part of his force up the slope, on both wings, in open formation, making the gun presence untenable. that they finally stopped and withdrew two and a half kilometers to the rear.

The second phase of the battle was executed by both fully deployed forces. By this time the Feds had reorganized their skirmishers, no longer two companies but three—from the 1st Colorado Volunteers, D on the right wing and A and E on the left. The federal left flank was precisely the most successful. With the Confederates constantly giving ground , a skillful cavalry charge in this sector forced some of the defenders, including elements of Company A of the 5th Texas Mounted Rifle Regiment, into a side canyon, where they were cut off. Davidson, present at this action, justifies the mess they have gotten into by alleging that the orders to withdraw did not reach them. Finally, part of the troops managed to escape thanks to a counterattack led by Captain Shropshire, then in command of the unit, from outside the encirclement. East, says Davidson

With a 46 cm long blade, the knives in question were terrible weapons with which “it was easy to cut a man in two with each blow”[16], he exaggerates without however the protagonist. The way was soon cleared and part of the unit managed to escape, although 27 men were lost.

The battle ended when Chivington, who did not know the exact number of enemies he had to face and had no artillery to support his troops, decided to settle for the outcome and retreat to the east side of the pass. In total, federal casualties amounted to 5 dead and 14 wounded; while the Confederates, caught by surprise and forced to retreat in disorder during the battle, deplored a casualty figure of 16 killed, 30 wounded, and 79 captured or missing, accounting for a third of their initial strength. Chivington had just won the first federal victory in the New Mexico Territory , and he was two days away from covering himself with glory.

The Battle of Glorieta

The events that followed the battle confirmed that Chivington had done well to retreat. As soon as the fighting had begun in the pass, Pyron had sent a messenger to the nearest friendly troops to come and assist him. It was late afternoon when a courier arrived in Galisteo, about 26 km southwest of Johnson's Ranch, with the horse almost blown up after an intense series of gallops. Barely ten minutes later Colonel William Read Scurry had formed his troops and set out . He had with him nine companies of the 4th Texas Mounted Rifle Regiment, four of the 7th, and a battery of four artillery pieces. In order to take advantage of the shortest path, the column advanced along barely marked trails and paths, it was a terrible night, Scurry would narrate:"We must recognize our brave men for having executed that march in the cold night, and indicate that where the path was too steep for the cavalry to drag the artillery, their harnesses were removed and it was the men who moved them, by hand and with good spirits, to overcome the accidents of the terrain.”[17] When they arrived at their destination, it was 3:00 a.m. on March 27. They were exhausted but both sides were going to take a break while they accumulated more troops, that day there was going to be no fighting.

The Battle of Glorieta, or Pigeon's Ranch , which took place on March 28, was undoubtedly the turning point of the campaign, but not because of what happened on the battlefield. Compared to the encounter on the 26th, both contenders committed more forces –about 1,300 Federals and 1,200 Confederates–, the battle was bloodier and it was the Confederates who ended up owning the land, but otherwise its structure was very similar to that of the Apache Canyon meeting, although as we have already said for the benefit of the southerners. Both vanguards came into contact after 10:30 and the battle began around 11:00. The Federals had established their front not far from Glorieta, at the canyon's eastern exit, but the Confederates were quick to drive them out. The fight took place in one of the least suitable natural settings, limited on both sides by steep slopes, especially to the west, criss-crossed by rocky ridges and dotted with pine forests. Once both forces were deployed, although the attackers executed several flanking maneuvers, in the end they had to repeatedly resort to assault. “[…] Although every foot of ground was vigorously defended, we pushed them steadily until they were in full retreat with our men in pursuit until exhaustion forced them to stop,” Scurry wrote triumphantly.[18] A succinct account that ignores fundamental aspects of the battle, such as the fact that there were three federal positions that the Confederates had to disrupt and that two officers of extraordinary importance died in the assault on the second:the Shropshire commanders – the man who had saved Davidson two days before – and Ragnet. Furthermore, “Major Pyron lost his horse, killed while riding it”[19], and Scurry was also wounded:“Two minié bullets grazed my cheek, opening a bloody wound, and my uniform was torn in two places.”[ 20]

It was between 5:00 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. when Slough ordered a retreat from the battlefield, leaving victory in the hands of his enemies. It must have been a sad moment for the Union soldiers, no doubt, as they returned to their starting point that morning at Kozlowsky Ranch, angry that they felt they had not been defeated and could still have fought. However, they had already suffered the loss of 1 officer and 28 men killed, while the wounded amounted to 2 officers and about 40 soldiers and the prisoners to 15; and although the Confederate casualty figures – Scurry puts total casualties at 36 dead and 60 wounded – were higher, they had maintained the initiative and superiority at all times, and we must not forget that the most dangerous moment in those battles was when one of the sides broke ranks and retreated in disorder. It was then that casualties rose exponentially, and no doubt Slough, having made his own decision to march against the enemy, was aware that if he could not achieve a resounding victory, he should at least avoid a costly one at all costs. withdrawal.

It was 10:00 p.m., when a column of exhausted troops entered the gloomy Federal camp, where the men continued to mutter about the victory they believed had been stolen from them. The news brought by those men would suddenly change everyone's mood. The Confederate supply train had been destroyed . The adventure had begun around 8:30 a.m. that day, when Major Chivington had set out west with a column of four hundred men made up of volunteers from both Colorado (four companies) and New Mexico (one company), as well as regular soldiers (two companies of infantry and one of cavalry). After an hour's march, the force had left the main highway and entered the mountains, following a steep path that ran through the heights south of Apache Canyon and that led directly to Johnson's Ranch, the Confederate camp, where, as he would indicate Chivington himself:“It was found that there were 80 carts gathered in the canyon, and a field piece. All in charge of about 200 men.”[21] It was Scurry's supply train, and those men would have been wounded, according to some sources, but this is doubtful.

The loss of these wagons filled with soldiers' ammunition, supplies, blankets, clothing, and officers' personal baggage was a disaster for the Confederate campaign , as his point of attack had just been unable to continue to Fort Union in search of essential supplies so that the entire force could stay on the ground. In the words of General Sibley himself, the success of Chivington paralyzed “Colonel Scurry to such an extent that he was two days without provisions or blankets. The patience and endurance of our men was absolutely extraordinary and is to be commended.”[23] To this destruction, Josephy adds the death of 500 horses and mules belonging to the Texan mounted riflemen, who had gone to battle on foot, surprised by the raiders and slaughtered by bayonet. It is also a figure that could be exaggerated.

Chivington's action was not, on the other hand, without its shadows. The fiercest criticism that was leveled at him also allows us to glimpse the hatred that could manifest itself between unionists and secessionists. In his second report, Colonel Scurry indicated that, after his success and informed that they were losing the battle at Glorieta, the federal

The other pending question is that of the royal mission of Chivington. At the end of his report, he mentions the presence of "a certain Mr. Collins", [25] who, following his own wish and supported by Colonel Slough, would have accompanied him. He was a man connected with Indian affairs who, according to the head of the raiding force himself, acted bravely and gave great service as a guide and interpreter, "although he did not burn the train nor was he the cause of it being achieved." [26] The phrase is somewhat petty, as if Chivington wanted to disprove something. What was his real mission? Lt. Col. Samuel F. Tappan, of the 1st st The Colorado Volunteer Regiment, which was in command of the Federals' left wing in the main battle, would mention in its report, written in May, long after the encounter, the possibility of meeting Chivington's men arriving from the Confederates' rear. . In fact, he indicates that he was ordered “to be ready to advance and attack the enemy flank as soon as he [Colonel Slough] did against the front, which he expected to do as soon as Major Chivington attacked from the rear, which he expected to do.” happen at any time.”[27] These orders seem to indicate that Chivington's real mission was to be in the rear of the Confederates during the battle , and not attacking his supply carts, and the fact that this issue is being raised so long after his success is no doubt a clue to his veracity, since otherwise Tappan would have had no business getting into it. such disquisitions. According to William Keleher, [28] it was actually Collins who had the idea to attack the Confederate supply train, and according to Josephy, [29] he was one of the scouts for Lieutenant Colonel Chaves, of the 2nd Army Volunteer Regiment. New Mexico, who located the juicy Chivington Dam.

Regardless of who took credit for destroying the supplies of Scurry's Confederate column at Johnson's Ranch, this action put an end to the Southern offensive .

As it would at Gettysburg more than a year later, the Confederacy had come as far as it could go, and now it would have to back off, never again to threaten the road to the gold mines, nor the upper course of the Rio Grande. For this reason, over time, the battle of Glorieta would be known in the region as the Gettysburg of the West .

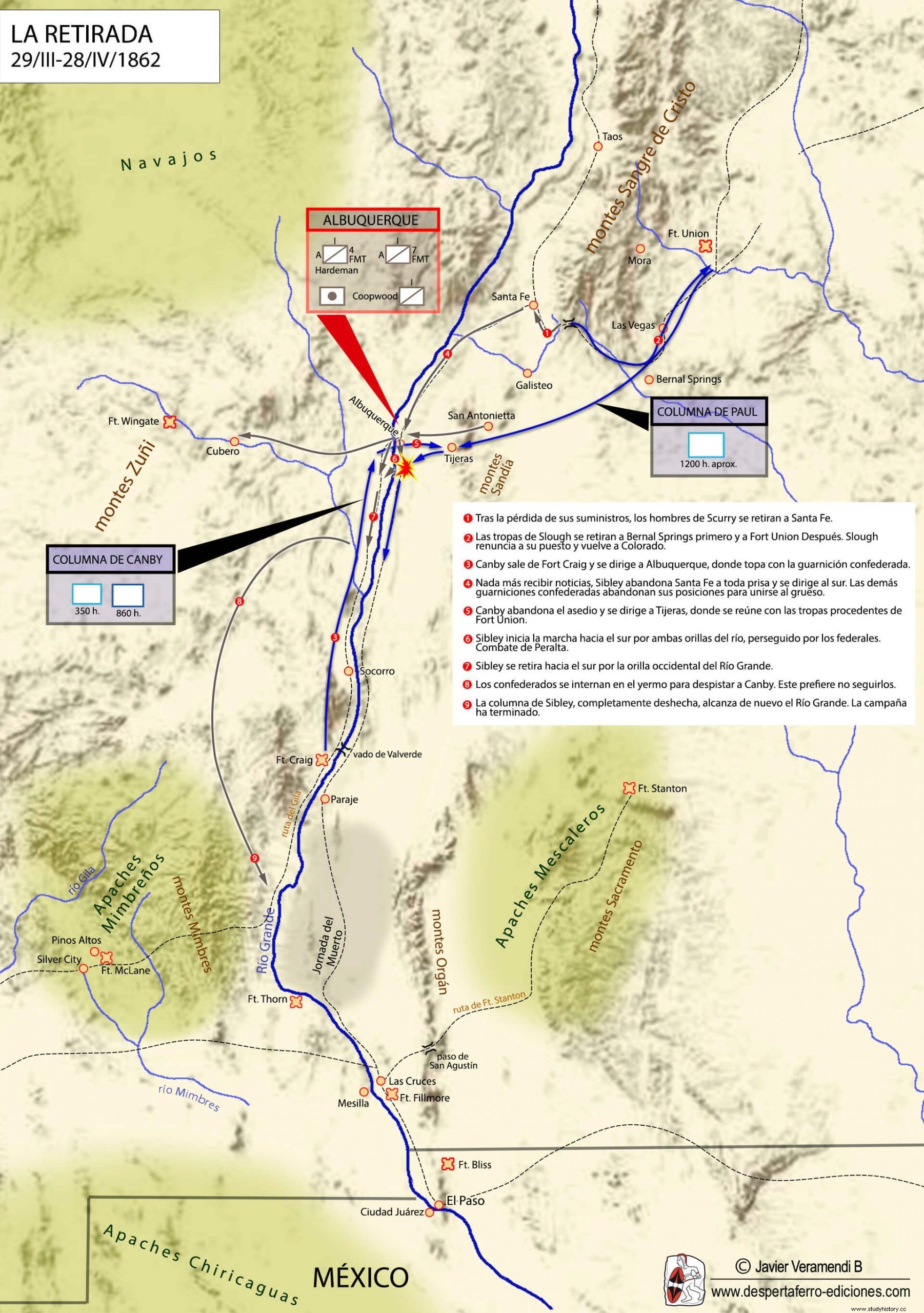

The withdrawal

“We have been surrounded by all kinds of difficulties, general and individual – Brigadier General Sibley indicated in the report of May 31 – Entire supply trains have had to be abandoned and, however scantily provided in blankets and clothing from the beginning, the men have abandoned, without a murmur, what little they had left.”[31] The point of this paragraph is very exculpatory, especially if it is linked to the desperate request for reinforcements contained at the end of the same report, which has been cited above. In any case, since the recipient of the text was in Richmond, far away at the end of a complicated line of communications, it was evident that he was not waiting for instructions, but was going to act on his behalf and he just wanted to make it clear that he was going to withdraw forced by circumstances.

In the meantime, important decisions were being made on the federal side as well. Canby, informed of Colonel Slough's actions, had sent a messenger ordering him to return immediately to Fort Union. The letter, which had left before he knew that there had been a fight in Glorieta, reached its recipient later, when he was camped in Bernal Springs, a town where he had arrived on March 30 after leaving the vicinity. from the battlefield. According to Arthur Wright, [32] the humiliation of this order after its success, coupled with the materialization of an assassination attempt by his own men during the battle, made Slough realize that the air in New Mexico was not good. for his health and, after retiring to Fort Union with his troops, resigned his post to return to Colorado . With this, Colonel Paul regained command of the Eastern Military District of New Mexico, and Commander Chivington took command of the Pike's Peakers regiment.

Meanwhile, Canby had decided to finally get going to join the Fort Union force and engage the enemy. “[…] my force (860 regulars and 350 volunteer troops) [plus four pieces of artillery] left Fort Craig on the 1st present and arrived at Albuquerque on the afternoon of the 8th.”[33] In Albuquerque, then, was Captain Hardeman, known as "Old Gotch," commanding a Southern garrison made up of Company A of the 4th Texas Mounted Rifles and Company A of the 7th, along with the company of Coopwood scouts and an artillery platoon.[34] All of them would defend the town for two days, until the federals decided to abandon the attack. There were two reasons that led Canby to renounce the taking of Albuquerque even though only about two hundred men defended it. One was, according to Josephy, [35] the desire to drive the Confederates back to Texas, so it was preferable for him to concentrate his forces with those coming from Fort Union as soon as possible and not complicate himself by taking prisoners; while Davidson[36] indicates another:the arrival of the bulk of the Confederate forces forced the Unionist colonel to abandon the siege of the city.

The siege of Albuquerque also had important consequences for the Army of New Mexico, which was in Santa Fe stockpiling what supplies and cars it had left and tending to its wounded and sick when A messenger arrived from Hardeman to report that they were under attack. Those who were in the hospitals receiving the necessary care, not only from the health workers of their own side but, in a sample of civilization in those wild territories, also from important personalities of the unionist side, such as "Mrs. [Louisa Hawkins] Canby , wife of General Canby, was there […]. Mrs. Canby won everyone's hearts by bringing delicacies to our sick and wounded,”[37] they had to choose between staying where they were and allowing themselves to be captured or otherwise join the retreating column , which had to speed up preparations on pain of being cornered in a territory that had already become very hostile.

Sibley's troops began their march back to Texas on April 7 in the morning. The first stage was Albuquerque, where the lack of draft animals and ammunition forced them to bury eight bronze howitzers that were no longer useful and where the column divided in two to advance along both banks of the Rio Grande. They left there on April 12 and two days later they were in Peralta. Meanwhile, on the 13th, Canby, who had been promoted to brigadier general, joined his force with that of Fort Union at Tijeras, in the Sandia Mountains, just east of Albuquerque, and began a swift pursuit of the enemy behind him. led two kilometers north of Peralta at dawn on the 15th. The Confederates, unaware of the presence of the enemy, continued to be divided into two groups, one on each side of the river. To the east, at Peralta, under Colonel Green, was the 5th Texas Mounted Rifles Regiment, or what was left of it, with the survivors of Coopwood's company and those of Pyron's battalion; while on the west bank and some 6 km further south was the rest of the force.[38] At 8:00 a.m. on April 15, the feds attacked the unsuspecting Southerners, who had been sleeping soundly while Green and the other commanders threw a party at Governor Connelly's residence. Canby came close to a major victory, but was thwarted by the withering reaction of Colonel Green, who immediately reorganized his force, sent a detachment to hold off the enemy, and entrenched his troops inside the town. The skirmish lasted until 2:00 p.m., when the arrival of more Confederate soldiers from across the river, coinciding with a blinding sandstorm, forced the attackers to desist. That night Sibley rallied his men on the west bank, putting the river between his force and the enemy's.

Protecting himself was not the only reason that had led the Confederate commander in chief to concentrate the column west of the Rio Grande, but that he had the intention of assaulting Fort Craig , a plan that had matured from the moment he learned that part of the federal troops that garrisoned it had left it. "My initial plan," Sibley wrote, "had been to advance downriver ahead of the enemy, gaining a two-day head start between Albuquerque and Fort Craig, attack the weak garrison, and demolish the fort."[39] However, as one and the other began to move south, in parallel, along both banks of the Rio Grande, the South American leader began to realize that he had not managed to distance himself sufficiently from his enemy and that he was facing the possibility that the fort held while Canby's force closed in from the north to take it over. At that time it had about two thousand four hundred men, nothing to do with the "eighty companies and eighteen pieces of artillery, which we estimate at about five thousand six hundred men"[40] mentioned by Davidson, who however is perhaps more reliable when indicating their own troops. “We had 1,302 men, many of them sick and wounded […]. We had twenty shells per cannon, nine cannons and forty shots for each man.”[41]

Realizing that his plan had little chance of success, and facing the increasing risk of being attacked before he even reached Fort Craig, [42] at sunset on April 17 Sibley decided to go all out and call a court martial.

Surprisingly, the Confederate general below lists the advantages of the new route:grass, and a firm path with very little difference in distance from the direct route, and the possibility of confusing the enemy "something that was later found to have been achieved."[44] However, if one attends to Davidson's memoirs, the decision was far from unanimous . Colonel Green, who at first had been in favor of going into the mountains, finally fell silent and did not opt for either option. Commander Coopwood was annoyed and eventually left the meeting to wander "back to Pyron's camp to 'talk' a little with the boys." Davidson indicates that he met some of his comrades who were loading their rations onto the horses in order that if they proceeded south they would escort the column until there was talk of surrender, then "they would go with Coopwood to the mountains." mountains and make their way to Texas.”[45]

Tomada, finalmente, la decisión de internarse en las montañas, Sibley ordenó abandonar todos los carros que no fueran absolutamente necesarios, cargando raciones para siete días a lomo de mulas. “En aquel momento, teníamos café y pan supuestamente para siete días –recordará Davidson–. Cuando terminó el consejo, se nos ordenó preparar nuestras raciones, destruir los carromatos, coger amas y munición y nada más, y comenzar a andar”.[46] Los heridos fueron abandonados en un hospital a merced de los vencedores y, aquella misma noche, el Ejército de Nuevo México se perdió en las montañas.

La agonía del yermo

“La ruta fue de las más difíciles y arriesgadas, tanto en su viabilidad como en lo que al suministro de agua se refiere”.[47] De repente, en el mismo informe de Sibley y apenas unas líneas más abajo, habían desaparecido la yerba y el firme del camino . “El éxito de la marcha no solo demostró la sagacidad de nuestro guía, sino que también se cumplió, noblemente, la promesa del coronel Scurry de que su regimiento sería capaz de llevar los cañones más allá de cualquier obstáculo, por formidable que fuera”. En un texto dirigido al alto mando confederado, Sibley tenía que ser triunfalista. Otros testigos del viaje iban a contradecir sus palabras con rotundidad.

18 de abril. El coronel Green había decidido llevarse tres carros para cargar a los heridos y enfermos que se produjeran durante la marcha, pero “el camino era profundo y muy arenoso –cuenta un soldado anónimo– y las mulas estaban en tan mal estado que apenas podían tirar de los pesados carromatos. Davidson[48] hizo atalajar todas las mulas a uno de ellos para, empujando las ruedas, hacerlo avanzar una corta distancia para luego volver y traer los otros”. El equipo de carreteros pronto fue rebasado por el resto de la columna y, finalmente, los carromatos tuvieron que ser destruidos.

Los testimonios de tres soldados anónimos recogidos por Thompson solo dan una idea aproximada del intenso sufrimiento al que se vio sometida la fuerza confederada . “El día 19 partimos muy temprano, marchamos a ritmo constante todo el día y acampamos en Bear Spring. La cabeza de la columna no llegó al agua hasta después de oscurecer, y hasta las 24.00 horas no hubieron bebido todos los hombres. El sufrimiento causado por la falta de agua fue intenso. Muchos se dejaron caer junto al camino, incapaces de ir más lejos”.[49] Todos ellos fueron abandonados. El día 20 “apenas había agua suficiente para que los hombres pudieran beber y cocinar, de modo que nuestros caballos y mulas tuvieron que pasar sin ella”.[50] El 21 “acampamos en un profundo cañón, dejando nuestra artillería en lo alto de la colina. Ese día tuvimos Fort Craig a la vista”.[51] El 22, “marchamos sin detenernos, todo el día bajo un sol ardiente. El sufrimiento por falta de agua ha sido horrible. Los más fuertes se precipitaron frenéticamente hacia delante para llegar hasta el agua antes de ser consumidos por la sed. Mientras que muchos de los enfermos y los más débiles cayeron para morir, los que solo estaban cansados se tumbaron a descansar y luego siguieron, arrastrándose, hasta el agua”.[52] El día 23 los hombres salieron tarde, y durante el camino pasaron por un punto de agua en el que solo se detuvieron brevemente para reabastecerse “y luego intentamos llegar al siguiente punto con agua, pero no lo conseguimos y tuvimos que acampar en seco, sin nada que comer. Solo teníamos un poco de harina y café, y nada de sal o manteca de ningún tipo”.[53] El 24 parece que la etapa fue más corta, unos 16 km hasta un punto en el que había comida, que alcanzaron a las 12.00 y se detuvieron hasta el día 25. “El día 25 marchamos por Sheep Canyon, y desde allí al Río Grande y una vez más estuvimos en el valle, sin enemigos entre nosotros y nuestro hogar, y sin más sufrimiento a causa de la falta de agua. No nos reunimos con nuestras provisiones hasta el 28.”[54] La ordalía había terminado por fin, al menos para los supervivientes.

Cuando la columna llegó a la región de Santa Ana y las tropas se acantonaron para descansar y recuperarse, Sibley ya no era más que la sombra de ese “peor enemigo” que habían tenido los hombres de Fort Fillmore al principio de esta historia. El incendio que prendió al convocar el consejo de guerra previo a que la columna se internara en las montañas, en el que defendió la opción de avanzar a lo largo del río y entablar un combate a todo o nada y rendirse si no quedaba otra opción, socavó completamente su autoridad ante los coroneles Green y Scurry, que a partir de aquel momento se hicieron cargo de la columna.[55] El hecho de que hiciera lo peor del viaje subido en una ambulancia junto con las esposas de varias personalidades proconfederadas de la región que marchaban al exilio no mejoró su reputación, y cuando apremió a la columna a moverse más deprisa abandonando tras de sí a los más agotados, perdió el poco respeto que aún le tenían sus soldados.[56] Tras el fracaso de la expedición y la apresurada retirada, tras abandonar definitivamente a la mayor parte de los heridos y enfermos e internarse en el desierto, tras cruzar llanuras secas y quebradas, agotados por la sed y el hambre, tras haber empujado a brazo los cañones de la batería capturada en Valverde, única fuente de orgullo de la brigada, y haberlos izado o descolgado uno tras otro por barrancos y escarpadas laderas, los hombres que volvieron a la civilización estaban completamente desmoralizados.

A pesar de todo, cuando redactó su informe definitivo en mayo de 1862, Sibley hizo un interesante juego de manos para convertir su expedición en un fracaso glorioso. En primer lugar, tras haber argumentado a favor de la invasión de Nuevo México ante el mismísimo presidente Jefferson Davis, se permitió afirmar que el territorio no valía nada:

En segundo lugar, por supuesto, convirtió la expedición en una serie de victorias :“En lo que se refiere a los resultados de la campaña, solo tengo que decir que hemos derrotado al enemigo en todos y cada uno de los encuentros, y siempre contra efectivos muy superiores; que de ser las peor armadas, mis fuerzas han pasado a ser las mejor equipadas del país. Llegamos a esta región, el invierno pasado, vestidos con harapos y sin mantas y ahora el ejército está bien vestido y bien suministrado en otros aspectos”.[58] El tercer punto de Sibley, fue quejarse de la falta de recursos:“La campaña se ha llevado a cabo sin un solo dólar en las arcas del departamento de intendencia”.[59] Y finalmente, decidió sacar a colación el estado de ánimo de sus hombres para, a la vez que los halagaba, reforzar la idea de que no merecía la pena volver a avanzar hacia el norte de Nuevo México:

Poco después, las fuerzas confederadas se replegaron hasta El Paso, y de allí a San Antonio, abandonando el oeste de Texas y dejando finiquitadas las ambiciones texanas y confederadas de construir un gran imperio en el sudoeste . Lo cierto es que, tras la conquista de Nueva Orleans por las fuerzas de la Unión, el estado de Texas tenía cosas más importantes en las que pensar –defender sus costas– y los ejércitos confederados estaban librando una dura campaña en los pantanos de Luisiana, por lo que, tras recibir reemplazos, la Brigada de Sibley fue enviada a Luisiana, donde llegó en la segunda semana de marzo. La impresión que causó en este escenario podemos leerla en las memorias del general Richard Taylor, comandante en jefe del Distrito Militar del Oeste de Luisiana, quien escribió:

En cuanto a los hombres, “eran resistentes y muchos de sus oficiales valientes y entusiastas, pero estas cualidades perdían valor debido a la falta de disciplina […]. Oficiales y hombres se dirigían unos a otros llamándose Tom, Dick o Harry, y sabían lo mismo de los grados militares que de la jerarquía celestial de los poetas”.[61]

Notes

[1] Estas tropas, que iban a partir desde Fort Yuma, en la frontera sudeste de California, se encargarían de expulsar a los confederados de Tucson y de reconquistar toda la Arizona confederada.

[2] Hay autores que indican que ese fue el día real en que partieron.

[3] La cuestión del ritmo de avance de los coloradinos es interesante y está poco definida. Tanto Whitford, W. C. (1906):Colorado Volunteers in the Civil War , como Josephy, p. 77, afirman que el día en que partieron fue el 22 de febrero, lo que da un total de 17 días de viaje y un ritmo de marcha de unos 26 a 30 km al día. Sin embargo, Cutrer, p. 107, y otros afirman que partieron el día 1, lo que para daría un total de 11 días de ruta y una media de hasta 40 km al día. Ambos coinciden en que se efectuaron etapas de 60 millas, lo que son 100 km, cosa muy poco probable si tenemos en cuenta que, de todo el regimiento, solo una compañía iba montada y el resto a pie. Como, de hecho, el regimiento estaba dividido en dos puestos, es posible que los del destacamento más cercano a Fort Union partieran el día 1, uniéndose a los otros en el camino.

[4] Hollister, Ovando J. (1962):Colorado Volunteers in New Mexico, 1862 . Chicago:Lakeside Press. p. 78. Hollister es uno de los defensores de la idea de que partieron el 1 de marzo.

[5] Así llamados por pertenecer a la gran oleada de gente que se desplazó a Colorado en busca de oro a finales de la década de 1850 y que, mayoritariamente, se instalaron en las faldas del Pike’s Peak (“pico de Pike”), al oeste de Colorado Springs.

[6] Informe del coronel J. P. Slough, del 1. er Regimiento de Voluntarios de Colorado, redactado en San José, Nuevo México, el 30 de marzo de 1862. No debe ser confundido con otro mucho más escueto redactado en el mismo lugar, pero el día anterior. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 534.

[7] Durante la Guerra de México.

[8] Carta del coronel Edward R. S. Canby al coronel G. R. Paul de fecha 16 de marzo de 1862, recibida el 21. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 653.

[9] Ibíd.

[10] Ibíd.

[11] Carta del coronel G. R. Paul al coronel J. P. Slough de fecha 22 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 654.

[12] Segunda carta del coronel G. R. Paul al coronel J. P. Slough de fecha 22 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 655.

[13] Con un total de 418 hombres. Informe del comandante J. M. Chivington, del 1. er Regimiento de Voluntarios de Colorado, fechado en Camp Lewis, cerca de Old Pecos Church, Nuevo México, el 26 de marzo de 1862, el mismo día de la batalla de Apache Canyon. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 530.

[14] Ibíd.

[15] Thompson, p. 82. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[16] Ibíd.

[17] Informe del coronel W. R. Scurry, del 4.º Regimiento de Fusileros Montados de Texas, fechado en Santa Fe, Nuevo México, el 31 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 542. Se trata del Segundo informe de Scurry, quien también escribió dos de ellos. en días consecutivos. “No sé si lo que escribo es comprensible. No he dormido en tres noches y apenas puedo mantener los ojos abiertos”, alega en el primero de ellos, fechado el día 30 de marzo.

[18] Informe del coronel W. R. Scurry, del 4.º Regimiento de Fusileros Montados de Texas, fechado en Santa Fe, Nuevo México, el 30 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 541.

[19] Ibíd.

[20] Ibíd.

[21] Informe del comandante J. M. Chivington, del 1. er Regimiento de Voluntarios de Colorado, fechado en Camp Lewis, cerca de Old Pecos Church, Nuevo México, el 28 de marzo de 1862, el mismo día del ataque al convoy de suministro confederado. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 538.

[22] Ibíd.

[23] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Albuquerque, Nuevo México, el 31 de marzo de 1862, en plena retirada hacia el sur. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 541.

[24] Informe del coronel W. R. Scurry, del 4.º Regimiento de Fusileros Montados de Texas, fechado en Santa Fe, Nuevo México, el 31 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 544.

[25] Informe del comandante J. M. Chivington, del 1. er Regimiento de Voluntarios de Colorado, fechado en Camp Lewis, cerca de Old Pecos Church, Nuevo México, el 28 de marzo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 539.

[26] Ibíd.

[27] Informe del teniente coronel Samuel F. Tappan, del 1. er Regimiento de Voluntarios de Colorado, fechado en Santa Fe, Nuevo México, el 21 de mayo de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 536.

[28] Keleher, W. A. (1952):Turmoil in New Mexico, 1846–1868 . Albuquerque:University of New Mexico Press. pp. 180-182.

[29] Josephy, p. 84.

[30] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Albuquerque, Nuevo México, el 31 de marzo de 1862, en plena retirada hacia el sur. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 541.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Wright, A. A. (1962):“Colonel John P. Slough and the New Mexico Campaign” en The Colorado Magazine , vol. XXXIX, n.º 2. Abril. pp. 89 y ss. El artículo explica detalles sumamente interesantes de la campaña, y analiza los motivos de Slough para dimitir.

[33] Informe coronel Ed. R. S. Canby, del 9.º Regimiento de Infantería, al mando del Departamento. Fechado en San Antonio, Nuevo México, el 11 de abril de 1862. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 549.

[34] Thompson, p. 101. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[35] Josephy, p. 86.

[36] Thompson, p. 102. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[37] Thompson, p. 99. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[38] Fundamentalmente el 4.º y el 7.º regimientos.

[39] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Fort Bliss, Texas, el 4 de mayo de 1862, tras la campaña. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 510.

[40] Thompson, p. 120. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[41] Ibíd.

[42] Davidson menciona una posible emboscada en Polvadera.

[43] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Fort Bliss, Texas, el 4 de mayo de 1862, tras la campaña. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 511.

[44] Ibíd.

[45] Todas las citas son de Thompson, p. 121. Testimonio de W. Davidson.

[46] Ibíd.

[47] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Fort Bliss, Texas, el 4 de mayo de 1862, tras la campaña. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 511.

[48] Este testimonio, recogido también por Thompson, p. 123, es de tres soldados anónimos de la columna, y en este caso se refiere al mismo Davidson cuyas memorias se han citado en diversas ocasiones.

[49] Thompson, p. 124. Anónimos.

[50] Ibíd.

[51] Ibíd.

[52] Ibíd.

[53] Ibíd.

[54] Ibíd. p. 125.

[55] Cutrer, p. 112.

[56] Josephy, p. 88-89.

[57] Informe del general de brigada Henry H. Sibley, comandante en jefe del Ejército de Nuevo México. Redactado en Fort Bliss, Texas, el 4 de mayo de 1862, tras la campaña. War of the Rebellion, a compilation of Official Records , serie 1, volumen IX, p. 512.

[58] Ibíd. p 513.

[59] Ibíd.

[60] Ibíd.

[61] Taylor, R. (1879):Destruction and Reconstruction:Personal Experiences of the Late War. New York:D. Appleton and Company. p. 126.