It is understandable that Christians wanted to give the death of an epic bath. Almanzor , in all probability, the most formidable enemy coming from the part of the Peninsula dominated by the Muslims. What better way to represent Almanzor's death than a great victory against his army from a coalition of Christian kingdoms on the Battlefield of Calatañazor , after which, defeated and humiliated, he flees to die in Medinaceli.

Lucas de Tuy , in his Chronicon mundi (written shortly after 1236) is the first to leave us an account of this battle:

This story is collected by the Archbishop of Toledo Ximénez de Rada, in De rebus Hispaniae (around 1244) with some variations:Almanzor was not returning from Galicia but entering Castile, the king of León Vermudo II promotes an alliance with Castile and Pamplona after Almanzor's attack on Compostela (year 997) and much of the blame of the Muslim defeat is attributed to divine intervention, which sends an epidemic of plague on the Saracens in punishment for the taking of Compostela.

The healthy habit of examining historical sources with a critical eye should be applied especially to the chronicles of the Spanish peninsular medieval kingdoms. For the authors of these stories, the propagandistic purpose far exceeds the importance of historical fidelity. To give just a few examples, we can cite the narratives about what happened in Covadonga and the origin of Don Pelayo, the mythical battle of Clavijo and the miraculous appearance of the apostle Santiago in it, or the legends related to the supposed independence of the county of Castile, such as that of the horse and the goshawk or the so-called Judges of Castile.

The same can be said about the Battle of Calatañazor . As I pointed out above, it is understandable that the Christian chronicles wanted to bathe the end of the most significant leader of the era of the greatest political and military pre-eminence of the Caliphate of Cordoba over the peninsular Christian kingdoms as an epic. However, the account by Lucas de Tuy, written more than two hundred years after Almanzor's death (which occurred in the year 1002) –and which was subsequently reproduced by Archbishop Ximénez de Rada– not only contains various historical anachronisms, but also that does not support analysis compared to other historical sources in relation to the death of the character.

Anachronisms in the story of Lucas de Tuy

Three are the main inconsistencies from the historical point of view about the events and characters mentioned by Lucas de Tuy and that could not take place in the year 1002, date of the death of Almanzor.

- It is indicated that the Muslim army was returning from the capture of Compostela which, as we have seen, did not take place the same year as Almanzor's death, but rather in the year 997.

- The participation in the battle of King Vermudo II of León. This monarch, who had ascended to the Leonese throne in the year 985, died in September of the year 999, so it is not possible that he was present at a battle in the year 1002.

- The intervention of the Count of Castilla García Fernández. This is a case similar to the previous one. García Fernández, son of Fernán González, was Count of Castile from the death of his father in the year 970 until his own death, precisely in Medinaceli, in the year 995. He was succeeded by his son Sancho García, who was Count of Castile in the year 1002.

Inconsistencies with other historical sources regarding Almanzor's death

Neither Muslim nor Christian sources prior to the Chronicon mundi (and, therefore, the closest in time to Almanzor's death) refer to the existence of a battle in Calatañazor and give a very different explanation about the cause of his death.

According to Muslim sources (Dikr Bilad al-Andalus and Almanzor's biography written by Ibn al-Khatib in his Kitab al-Ihata fi Tarif Garnata) Almanzor died during the expedition that he organized in the year 1002 to punish the Christian kingdoms, and especially the count Sancho García de Castilla , who had been on the verge of defeating him at the battle of Cervera in the year 1000.

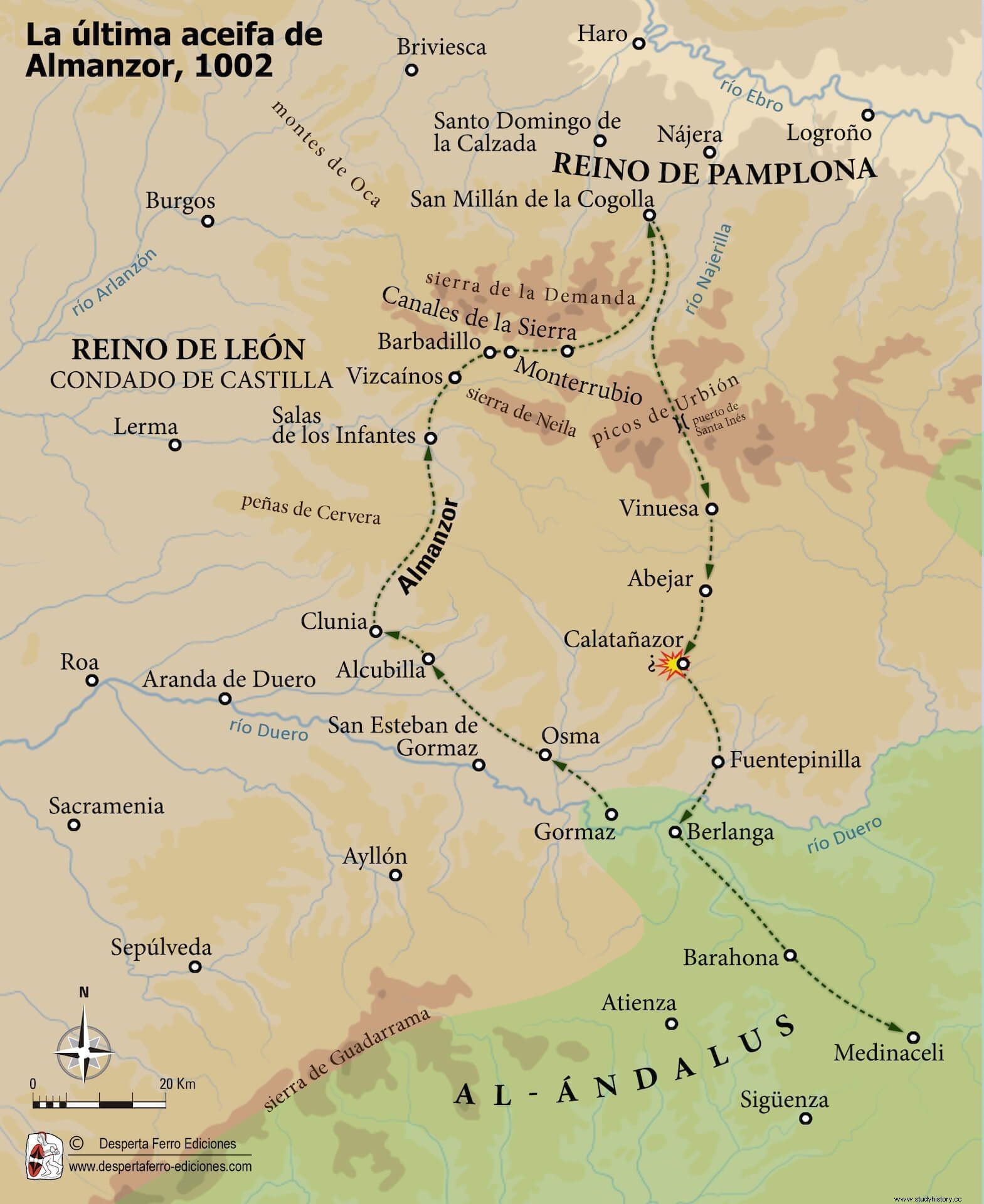

According to these same sources, Almanzor advanced from Clunia towards Salas de los Infantes, Pinilla de los Moros, Vizcaínos, Barbadillo, Monterrubio and Canales. In a new symbolic gesture, like that of the attack on Santiago, he reached the monastery of San Millán de la Cogolla, in La Rioja. The monastery was in the kingdom of Pamplona, but very close to the border with Castile, and San Millán was considered the patron saint of Castile. Many Castilian pilgrims and pilgrims from both kingdoms flocked there.

Almanzor's choice of this objective, apart from the usual one of ruining and destroying the enemy territory, was to humiliate his two main rivals at the time:the Count of Castile and the King of Pamplona Almanzor managed, effectively, to burn down and destroy the monastery. But there he suffered an attack of gout (a disease he had been dealing with for twenty years). Almanzor ordered the withdrawal and was taken in a litter to Medinaceli, where he died.

Older Christian sources say little about how Almanzor died, beyond expressing her joy and relief for him. The Burgense Chronicon he limits himself to reviewing that “in the year 1002 Almanzor died and he was buried in hell”. The Silent Chronicle gives some more details:"after many and horrible massacres of Christians, he was snatched in Medinaceli, a great city, by the devil, who had possessed him in life, and buried in hell."

The first mention of a confrontation is given by the Crónica najerense (from the second half of the 12th century):“in the thirteenth year of his reign, after many and horrible massacres of Christians, fighting with said Count Sancho and fleeing, he burst in half and died in the town called Grajal and he was buried in Medinaceli”. In any case, it must be taken into account that neither the date of the year of his "reign" (which began in 978) nor the reference to the town of Grajal are true, which casts doubt on the rest of what narrated.

The battle of Calatañazor, a myth?

The lack of mention of the Battle of Calatañazor in the Muslim sources and in the Christian sources closest to the year in which it supposedly took place, together with the inconsistencies and anachronisms contained in the sources that do narrate the battle, lead to the conclusion that the battle of Calatañazor never took place , and is a later addition to the propaganda from the time of Alfonso X. Rubén Sáez points out the possibility that Count Sancho García could have carried out an attack on the Saracen rearguard that was returning to Córdoba after Almanzor's illness, and that said attack It would have taken place in the vicinity of Calatañazor, which would be at the origin of the legend, but in no case would it be a Christian victory over Almanzor himself that would cause his death. It was nothing but part of the imaginary constructed by the propaganda of the Christian kingdoms to endow with epicness and defeat the death due to illness of the great Muslim leader Almanzor.

Bibliography

Álvarez Palenzuela, V. Á. (Coord). (2017). History of Spain in the Middle Ages . Barcelona:Ariel.

Manzano Moreno, E. (2015). History of Spain. He medieval few, volume 2. Madrid:Critique.

Martínez Díez, G. (2005). The county of Castile (711-1038). History versus legend II. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

Sáez, R. (2008). The campaigns of Almanzor (977-1002) . Madrid:Almena Editions.