After the death of Napoleon III (January 9, 1873), the heir to the imperial crown was his son, born in 1856, then a student at the military school in Woolwich. Six years later, the young Louis-Napoleon, tired of an idle life in England, decided to serve the British crown in South Africa. At that time, the English were fighting in their Cape colony against the Zulu tribe. The prince received permission to take part in the operations, as an attaché on General Chelmsford's staff. Leaving in February 1879, he was to be killed in action the following June.

1894

Five or six crude huts in South Africa, at the bottom of a narrow valley, near the confluence of the ltelezi and its tributary the lmbazani. Closing the horizon, the emaciated peaks of the Draken-Bergen.

All around the kraal, the immense and treacherous veldt:gigantic reeds with wigs, cacti with arborescent stems whose thorny arms rise like gibbets; here and there, rare palm trees profile their fusiform silhouettes, blooming in heavy plumes.

On the right, a deep donga with steep edges; on the left, a field of corn, its flowers and its large spiky ears complete, ten meters away, to blind all sight.

Today Sunday June 1, 1879, Whitsunday, the holy day of Pentecost.

The afternoon is advancing:almost four o'clock and the sun is going down behind the hills.

A small troop of horsemen occupies the kraal :the reconnaissance led by the Prince Imperial and Lieutenant Carey. Six Europeans, all volunteers from the irregular cavalry of Natal, compose it with them:Sergeant Willis, Corporal Grubb, Privates Cochrane, Letocq, Abel and Rogers.

They are lying down and talking about the grass. Seated apart, the two officers chat together. The Prince Imperial's companion is a man in his thirties, with a phlegmatic appearance, mustaches and chestnut sideburns in fins, glaucous eyes, a little shifty.

They have first spoke of colonial expeditions, Lieutenant Carey having served in India; they are now talking about the great uncle and his Italian campaign. The names of Arcole, Rivoli, Montenotte, Millesimo ring proudly in the pure sky, dark blue, almost indigo, marvelous limpidity that no cloud disturbs.

We are gone since nine o'clock in the morning. In a hurry. The prince barely found the time to scribble for his mother this supreme note, novissima verba which will reach him long after the funeral, the atrocious news:

Koppie Allein, June 1, 1879

My dear mother,

I am writing to you hastily on a sheet of my notebook; I am leaving in a few minutes to choose the place where the 2nd division is to encamp on the left bank of the Blood River. The enemy is concentrating in force and an engagement is imminent within eight days. I don't know when I will be able to give you news, because the postal arrangements leave something to be desired. I did not want to lose this opportunity to embrace you with all my heart.

Your devoted and respectful son,

Napoleon.

Everything is indeed ready for the march forward. The night before, Lord Chelmsford dictated his last orders. The division he commands and the mobile column of General Wood will unite their efforts:the Blood River crossed, they will go to Ulundi. Colonel Harrison will send the useful camp to designate the resting places.

A seemingly easy and harmless task in a region that has been explored many times:also, when Lieutenant Bonaparte insists on joining the little expedition, didn't he think he should refuse her this pleasure.

Unfortunately - it will be the first fatality that presides over these moments governed, it seems, by a mysterious Ananké - unfortunately the headquarters was in no hurry to act. In his mind, it is Major Bettington, his best vanguard officer, who will lead the reconnaissance. Only he waits too long to warn him and Bettington has already received another mission.

Second fatality:an officer shows up, who asks to take the place of the impeded major.

He is called Captain Carey:Jahleet Brenton Carey. He has good service records, but he is a newcomer. a brand newcomer.

Without thinking, much too thoughtlessly, when he has officers he knows better at hand, that we could form a larger escort composed of men of choice, Colonel Harrison hastens to designate Captain Carey, confining himself to this vague recommendation:

You will watch over the prince (You look after the prince).

You will watch over the prince (You look after the prince).

This which will be harshly reproached to him later:with good reason.

At nine o'clock, the small troop mounts on horseback. Escort under captain Carey, notes the prince in his notebook. Which will make Captain Glander exclaim, during the subsequent investigation:

It's the voice from the grave!

It's the voice from the grave!

“ALERT!”

THE ZULUS! »

The horsemen drove into the bush where they quickly disappeared. Leaving Fort Napoleon on the right, and heading east, they climbed through the dark bush a rather rough plateau from which the whole region can be seen.

Towards noon, we descended into a stony ravine, the dry donga of the Ity oty osi. Painfully we climbed the other side among the disintegrated shales that rock and roll under the steps of horses. Then we stopped not far from an apparently deserted kraal.

It is very badly chosen, this place where you

let's walk land for lunch. Bettington,

old trucker, Bettington, certainly,

he wouldn't have adopted it. Everywhere tumultuous vegetation, limiting the view, not allowing any. monitor approaches. And Bettingon again, no doubt, would have liked to ascertain whether the ashes of the hearths scattered in front of the huts have really cooled. We settle down in this hornet's nest; we are late. The blood has been unstrapped, no debt has been laid; Martini rifles

are not even loaded. From time to time, big red, lanky dogs, afres hounds come prowling around the bivouac. .their presence does not give the awakening either. mprecautions and negligence for which Carey will later try to lay the blame on the missing companion who is no longer there to justify himself:

I was not in command of the escort and had to comply with the demands of the prince who appointed him- even the place of our halt.

I was not in command of the escort and had to comply with the demands of the prince who appointed him- even the place of our halt.

Inadmissible defense in the mouth of an officer known for his stiffness in the service. The one he thus incriminates has always, on the contrary, given the example of discipline:a simple lieutenant in succession, without regular rank, how could a superior, captain of the royal army in the North Staffordshire regiment, have been subordinated to him?

June is our December in the southern hemisphere. Four o'clock passed:dusk is already announced in the sky which slowly turns to copper. You have to think about the return.

The prince is busy finishing a last sketch. Never had he been so gay, so happy to live! Suddenly the noise of a panting race:the Basuto, which for a few minutes had been spinning in the grass, appeared out of breath:

Alert! Zulus, Zulus!

Alert! Zulus, Zulus!

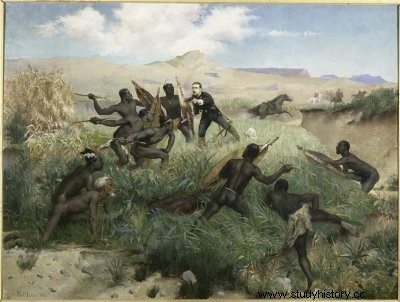

At the same time gunshots ring out; Cavalier Rogers collapses. About fifty frizzy-haired, oily-skinned warriors rush forward, brandishing their assegais, with hoarse cries. The whites ran to their rearing horses.

Save who can! claims Carey.

Save who can! claims Carey.

Since in the English army, it seems, honor and its code do not reproach such an order in desperate cases.

Him -even is already far, spurring his mount in a frantic gallop. He flees at full speed, without looking back, without looking back. 'You will watch over his Highness,' Colonel Harrison said.

The men imitate their leader. The prince, in turn, wants to jump into the saddle. He grabs the pommels, tries to pull himself up. His calm beast, terrified by the gunshots, kicks back and defends himself.

Please, sir, hurry, cries to him as he passes Letocq, a former sailor from Guernsey, down for a moment to pick up his rifle.

Please, sir, hurry, cries to him as he passes Letocq, a former sailor from Guernsey, down for a moment to pick up his rifle.

Then he escapes, saving his skin.

Clinging to the stirrup straps, the prince now runs alongside Fate; obeying the instinct that pushes him to catch up with his peers, the animal leads him towards the donga, out of the murderous circle. Blacks are on his heels; he redoubles his desperate efforts to get away. Perhaps he will succeed, when he gives up the stirrup leather to which he is attached. Newly sewn up, it has just broken under its weight.

Third and final fatality.

He tumbles; his sword, that beautiful sword of which he is so proud, a gift from the Duke of Elchingen, springs from its sheath; Fate's hooves bruise her shoulder. At the opposite summit of the ravine, Carey, Willis and the others saw his fall. Will they turn around, try to save the one in their custody?

In Zululand, any dismounted man is a dead man, the captain will answer dryly to the inquiry; I would have had my people killed unnecessarily.

In Zululand, any dismounted man is a dead man, the captain will answer dryly to the inquiry; I would have had my people killed unnecessarily.

They accelerate their escape; before dying, the abandoned will have time to see them disappear. I have before me the wounded gladiator; he consents to death, but conquers agony. Did these lines of Childe-Harold sing in the memory of the Prince Imperial, when he rose to conquer his own?

He sees himself lost:the grimacing savages who charge are already on him. At least, in his last battle, he wants to fall like a soldier. A first spear whistles; he pushes her away with his arm, as he used to do in Dundee. Once, twice, three times, he unloads his revolver and two niggers fall.

But he slips as he breaks, has no time to regain his balance; a barbed javelin hit him in the left side, another punctured his right eye, penetrated his brain. He collapses; the fight did not last a minute.

Found after the campaign, the seven warriors of Zétéwayo, who took part in this unequal struggle and provided the above details, will be questioned. Only one is missing among them, Zabanga, who delivered the mortal blow, slain at the capture of Ulundi.

How, you will ask, did this young man look when he fell? Did he look like an ox being knocked out?

How, you will ask, did this young man look when he fell? Did he look like an ox being knocked out?

No, he looked like a lion.

No, he looked like a lion.

Why do you say he looked like a lion?

Why do you say he looked like a lion?

Because it is the bravest animal we know.

Now the Zulus are stripping the body lying on the trampled ground, the body which they have continued to pierce with their spears to ensure that he is indeed a corpse. They share the weapons and the clothes, but they leave, on the bloody chest, the cross and the blessed medals hanging from their golden thread. A brave man, to find peace, must he not present himself before his gods with his amulets?

Thus dies at twenty-three, in a distant land, in a dark scuffle against negroes, dies uselessly, victim of his reckless bravery, the audacious stalker of glory haunted by too big dreams, the heir of Caesar who wanted to continue his fortune.

Eight hours:the French journalist Deléage , who dined in the Royal Artillery mess, is approached on his way out by a staff officer:

Something must have happened to the Prince Imperial. We saw him fall and his horse came back without him.

Something must have happened to the Prince Imperial. We saw him fall and his horse came back without him.

The Figaro correspondent rushes to Colonel Harrison; Lord Chelmsford, gloomy and upset, confirms the news. Where's Captain Carey? He writes in his tent; the journalist questions him, can only draw embarrassed words:a surprise; the prince has not reappeared; he doesn't know anything else. The Frenchman returns to Colonel Harrison; Lord Chelmsford is still there deep in conversation.

General, please send a detachment to find the prince. Perhaps he is only wounded, and if, by misfortune, he has ceased to live, are we going to leave his body delivered to the brutality of savages, to the voracity of birds of prey and carnivorous beasts?

General, please send a detachment to find the prince. Perhaps he is only wounded, and if, by misfortune, he has ceased to live, are we going to leave his body delivered to the brutality of savages, to the voracity of birds of prey and carnivorous beasts?

The answer comes, cold and harsh:

No, sir; impossible, too dangerous on this dark night.

No, sir; impossible, too dangerous on this dark night.

Mr. Deléage insists; he is made to understand that he is becoming importunate. He withdraws in despair.

they too Captain Molyneux, aide-de-camp to Lord Chelmsford; here is what, in the evening, he reports to his boss:

To His Excellency, Lieutenant General

Lord Chelmsford K.C.B.

Camp between Inunzi and Itelezi, June 2, 1879.

My Lord,

In accordance with your instructions, this morning I accompanied the cavalry commanded by Major General Marshall to find the body of His Highness the Prince Imperial.

The scouts from the flying column under Brigadier General Wood joined on our left, and together we searched around the kraal.

We soon discovered the bodies of the two troopers of Native. At nine o'clock Captain Cochrane called my attention and that of Surgeon-Major Scott to another body in the bottom of a donga, which, on examination, was recognized as that of His Imperial Highness.

It was about two hundred yards northeast of the kraal, about half a mile from the junction of the two rivers.

The body was entirely stripped, except of a gold chain, with medals, which was still around his neck. His sabre, his revolver, his helmet and his other clothes were gone, but we found in the grass his spurs with their straps, and a blue sock marked N. I have all these objects with the chain in my possession.

The corpse bore seventeen wounds, all in front, and the marks on the ground, as on the spurs, indicated desperate resistance. At ten o'clock, a stretcher having been formed with spears and blankets, the body was carried to the donga by officers up the hill towards the camp. At eleven o'clock the ambulance arrived; the C(,r,,-corp was deposited there and detachments commanded by officers of the Dragoons of the Guard and the 17th Lancers escorted it to the camp where we arrived at two fifteen in the afternoon.

I have the honour... etc.

W. C. F. Molyneux,

Captain in the 22nd Regiment A. D. C

Now the bloodless remains, the gutted remains lie on an operating table. Doctors Scott and Robinson are busy stuffing it with aromatic plants. They toil all night; at dawn, the stitched up corpse is locked in a makeshift coffin, a zinc box hastily made by the soldiers of the engineers with tea chests.

On the plateau, opposite the camp, a funeral ceremony unfolds its pomp. The English regiments were formed in a square:in front of their alignments passes slowly

a field piece and its extension

In the center, in front of the rolled-up coffin of the tricolor flag , an Irish Catholic chaplain recites the last prayers. The troops file past, all their officers saluting with sabers; and the Union-Jack Gules. to the canton quartered azure, gently lowers to the ground, as a sign of royal homage.

Two. hours later, the army moved on. While she is marching to this victory of Um Volosi which will consummate the disaster of Zétéwayo, the one who had dreamed of it so long is moving heavily towards the coast, his van flanked by a squad of spearmen.

Under the thrill of half-mast flags. to the death knell of all the bells ringing. military honors are once again returned to Durban. The population is in mourning:what remains of the garrison is on its feet.

A funeral oration for a madman, General Butler, the arms commander, wrote a special order of the day that is not without grandeur:

Following the coffin which contains the body of the last prince imperial of France and giving to his ashes the last tribute of sadness and honor, the troops of the garrison will remember:

I° That he was the last heir of a powerful name and of great military renown;

2° That he was the son of England's staunchest ally in days of danger;

3° That he was the only child of a widowed Empress, who now remains without throne and _without posterity, in exile, on the coasts of England.

To penetrate more deeply still of the pain and the respect that one owes to this memory, the troops will also remember that the imperial prince of France fell while fighting like an English soldier.

Then the Boadicee embarked the coffin, transhipped at the Cape on the Orontes, which immediately set sail for Europe.

At Chislehurst, the Empress was worrying. Her son's letters, voluntarily carefree and light, failed to reassure her.

Time passes and, day by day, the obsession grows stronger:so powerful that she agitates the project of going to join him in Africa. Queen Victoria, informed, comes to her aid; Lord Wolseley, who is leaving to succeed Lord Chelmsford, seems to have received orders to send the prince back to Europe.

On the night of June 1 to 2, a hurricane ravaged Camden Place park A willow is carried away, of which Mr. Strode has, it is said, brought back the cutting from Saint Helena, taken from the tomb of the Emperor. Sees in it an intersign, the fatal omen of a catastrophe:his terrors are redoubled. linking South Africa to the metropolis did not exist at that time:transmitted from Funchal, it did not reach its addressee until June 19.

Queen Victoria showed herself to be deeply affected by the misfortune who struck his friend. At all costs, it was necessary to prevent her from learning about it from the newspapers:Lord Sydney received a mission from the German er prepare for the dreadful jerk. Introduced to the Duc de Bassano. he carried out his sad message.

The grand chamberlain's unfailing loyalty, his age and his job reserved for him the cruellest honor of his entire career. He announces himself to the Empress. She writes in her room, she writes to her child. Seeing this trembling visitor enter. her face pale and crestfallen, she leaps up, searches him with her gaze:

My son?

My son?

Quiet.

Is he sick, injured?... I'm going to leave... But speak up!

Is he sick, injured?... I'm going to leave... But speak up!

Silence.

So she understands and falls down.

Paris learned of the Prince Imperial's death. of this little prince” whom he had loved, on June 21, by a special edition of the Estafette. He was immediately upset by it, and his emotion grew even more in the days that followed.

The contrast between this lamentable end and the prestigious birth in all the glory of the throne lent itself to easy literary amplifications. And everyone felt that the seal had just been put by fate on all the hopes of an imperial restoration.