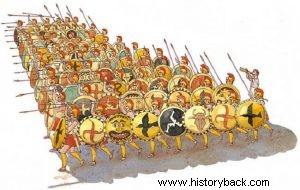

The hoplite phalanx was not a simple standard deep battle formation like its predecessors. The formation and the battle system introduced with it (according to tradition) by Argios Pheidon constituted an unprecedented military revolution, which was to determine the fate of Hellenism some two centuries later, in the Midika.

If the Achaean Epetis , heavily armored, lance-wielding charioteer or the sarissaphorus of the Minoan and Mycenaean armies were unpleasant surprises for their opponents, the armored phalanx was the catalyst, the secret weapon and the power multiplier of the Greeks in the face of new challenges.

The phalanx was formed in pairs. The greater its depth in yokes, the greater its cohesion, but also its thrusting power. The maintenance of order was a matter of prime importance to the phalanx. Initially the hoplites were also equipped with javelins which they charged against the opponents before the contact of the opposing phalanxes.

Depth, access, combat

Gradually, however, the javelins were withdrawn from the hoplite's arsenal precisely because their hexapelting disturbed the cohesion of the phalanx. The phalanx was deployed at a depth of 4, 6, 8, 12, 16 or even 50, according to Epaminondas, yokes. Its usual depth was that of 8 (single phalanx) and 16 even (double phalanx).

Spartans, in classical times, usually lined up 6 (single phalanx) and 12 (double phalanx) yokes deep. The lesser depth of the Spartan phalanx was more than compensated by the excellent training of the Spartan lancers and was a response to the permanent almost numerical superiority of their opponents. However, the depth of the Spartan phalanx could be varied.

Originally the phalanx had the same depth of yokes along the whole line. But then, as evidenced by the battle of Marathon, and especially from the time of the Peloponnesian War and until the reappearance of the sarissa, the depth of the yokes of the various parts of the phalanx was variable and dependent on tactical conditions.

The conflict between two opposing phalanxes was distinguished in two phases. The first started with access. Usually the phalanx did not statically receive the attack of the opponent. They moved against the opponent with the men chanting the paean while the beat was provided by musicians – usually a flute. The hoplites moved with a slow and steady step, which they accelerated as the distance from the opponent decreased.

The Spartans were renowned for their slow, rhythmic march – to maintain order and cohesion – pipe accompaniment. The distance that usually separated opposing armies was no more than 500 meters. At Marathon, however, the distance between Greeks and Persians was of the order of 1000 meters.

After, in the manner described, the two phalanxes crossed the space between them, the hoplites joined forces (the visors of their shields touched each other) and literally fell upon their opponents, after first shouting loudly. The shields of the men of the first yoke of one phalanx touched the shields of the opponents.

The men of the first two yokes, pressed by the men of the rear yokes, threw their weight on the poles. But at the same time they speared the opponents. During the impact many spears were nailed to the opposite shields and broke. Then the hoplites drew their swords and, always pressed by those behind them, tried to strike the enemies.

During the gunfight phase the losses of the opposing armies were usually minimal. Well protected behind their breastplates and large shields, the hoplites were not easily wounded. For better results, the spear was held in a high grip, above the hoplite's head.

Champions in javelin were of course again the Spartans, who were so well trained in achieving precision strikes that they often decimated opponents before their phalanx even made physical contact with the enemy.

But usually the opposing phalanxes remained for a time in close contact, their men pushing with their shields against the opposing wall of shields and the clang of weapons vibrating the air. It was precisely in this second phase, the push phase, that the depth, but also the courage, endurance and discipline of the men of the phalanx decided the result.

A phalanx drawn double deep (16 fathoms) was almost certain to prevail after a certain time over a simple phalanx 8 fathoms deep, unless its men were completely inexperienced. A conflict of this nature was particularly arduous for the warriors, who also carried equipment with a total weight of at least 30 kilograms.

In order to cope with the fatigue of the fighters, the Greek generals of the period applied the maneuver of successive engagements of a specific number of evens of the phalanx each time, effectively keeping regular reserves. The overworked yokes of soldiers were then replaced by the reserves. This tactic was applied by Leonidas in the battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC.

At some point one of the two phalanges, either due to fatigue, or due to a greater depth, or due to being overwhelmed by the opponent, "broke", that is, its forehead was torn. This very phase was the most disastrous for the defeated. Having lost its organic and physical ties, the fragmented phalanx section became a group of individually fighting squires, which could not face its coordinated opponents.

Usually after their front was broken the vanquished fled, pursued to a point by the victors. Fugitives, in order to run faster, threw away their shields – they became throwers .

Of course the strongest opponents of the Greeks were the Greeks. When the hoplites faced foreigners things were usually simpler for them, unless the polemians had great numerical superiority, making them able to outflank the phalanx.

The great weakness of the phalanx was the vulnerability of its right flank, where the extreme hoplite had no colleague next to him to cover him. For this reason, traditionally, the most elite men lined up on the right wing of the Greek artillery phalanxes.

If the opponent possessed reasonable arithmetic the lagging phalanx could extend its front, reducing the depth of its scales. However, against opponents like the Persians, who had an overwhelming numerical superiority, other solutions had to be found. Thus at Marathon Miltiades ordered the two horns of the phalanx to a depth of 8 fathoms and the center to a depth of only 4 fathoms. The Persians lined up in "sparabara" formations, up to 100 men deep.

But only the first pair of men had shields. All the rest carried only a short spear, handbook and bow. Thus, as soon as the Greeks, applying the tactic of pushing, "broke" the first yoke of shield-bearing Persians, the rest simply began to be slaughtered by the Greek spears. At Plataea something similar happened, until the Tegeans and Spartans rushed out, once again broke the Persian line of shield-bearers and slaughtered the Persian archers.

Gradually the tactics of using the phalanx were developed. The Peloponnesian War was the great war school of the Greek generals. The hoplite's equipment became lighter, with the abandonment of the breastplate and shins. Then the guys from Ekdromos appeared hoplite

Rangers were usually the youngest, purposely unarmored to be faster and more agile. They were the vanguard of the phalanx and pursued the opposing psilis and peltasts who pinned it down with their missiles. They also undertook the pursuit of defeated opponents.

The phalanx became much more flexible and able to transform according to tactical needs. From the parallelogram monolithic formation that had initially developed into a multitude of battle and access formations – convex, hollow, in bend, piston, cavity, seeded, production, coupling, etc.

This flexibility was achieved by dividing the phalanx into tactical sub-units. Subunits existed from the time of the invention of the specific formation, but they had a more traditional role - tribal and not so utilitarian. The basic subunit was the company, which, however, depending on the city and the era could include from 100 to 300 men.

The company was headed by the captain. In classical times the strength of the company was 100 men. Later, other units were formed, which included a number of companies. Typical is the regular use of companies of hoplites as shown by Xenophon in "Kyrou Anavasis" and in "Descent of the Myrias".

Such units, at the "battalion" level so to speak, were the Spartan Mora, with a strength of 400-600 men or the regiment whose strength varied from city to city and from era to era. Subunits smaller than the company in the Spartan army were the pentecostya (usually two per company) and the enomotia (two per pentecostya). Similar subdivisions of the company existed in the other Greek armies. The corresponding subunit of the confederation in the other armies was the stoichos (16 men).

Apogee

From geometric times up to the 4th century BC. the phalanx, as a battle formation, evolved and adapted to the new conditions, but also to the new "weapons" that made their reappearance on the Greek battlefields (cavalry, peltasts). However, the phalanx was to reach its peak of development precisely in the 4th century by the famous duo of Theban generals Epaminondas and Pelopidas.

The Theban generals, also due to the small strength of the Theban army, invented a new method of deploying the phalanx, the Slanted Phalanx . The two Theban generals realized that with their small forces it was impossible to cope with the opposing armies, especially the Spartan one.

That is why they thought of another way of lining up their army which would neutralize or even inactivate their outnumbered opponents. The tactic of the oblique phalanx was simple. The army was divided into two horns, the offensive and the defensive.

The offensive horn was endowed with the bulk of the hoplites, the breaching mass, laid at a very great depth, up to 50 yoke. The rest of the line's front was formed by the defensive horn, a thin phalanx of hoplites, no more than 8 fathoms deep. The flanks were covered by cavalry and light divisions.

In this way, regardless of the numerical strength of the opponent, the two Theban generals were able to achieve catalytic, local numerical superiority at the pre-selected point of the enemy front. With the implementation of the tactic of the oblique phalanx, the weapon system of battle had reached its peak.