As in the Middle Ages there was no ZUS or its counterpart, the burden of supporting the aging parents was entirely on the children - especially in the countryside. Whether they like it or not, they had to pay for the father and mother - and the list of their duties was much longer than at present. What was required of them?

The living father could hand over the leased land to his son, who then undertook to equip a room for his parents and provide them with food. This custom was immortalized in the medieval story The Divided Horsecloth ( Horse rug divided ) that has survived in several versions.

In addition to the proverbial glass of water, adult children had to provide their parents with a place to live, food and all the necessary equipment.

The most popular of them looks like this:a peasant, to whom an elderly father gave what he had, got tired of supporting his parent and decided to get rid of him from the house ; So he ordered his son to bring the old blanket and tell him to go away. The boy cut the blanket in two and gave his grandfather only one, telling his father, "I'll keep the other half until I grow up, and then I'll give it to you."

Fine for breach of contract

Most of the parents, however, preferred not to rely on the blind fate and gratitude of their children in their old age, but only meticulously wrote down their offspring's obligations to each other in court courts, and violations of these provisions were punished with fines.

In 1278, on the Ellington estate belonging to Ramsey Abbey, William Koc admitted that he had not given his father the grain, peas and beans that he owed him for a year under a contract by which his father gave him the land he farmed. So a new deal was made on this, and William's two guarantors, the peasants who bailed him out, were fined sixpence (not a small sum, considering that the pence was silver at the time).

In 1294, a family from Cranfield, another settlement on the Ramsey Abbey estate, even predicted that older and younger members might not live in harmony with each other. Elyas de Bretendon and his son Jan agreed that the latter would provide accommodation and "enough food and drink" for Elyas and his wife Christine at their home.

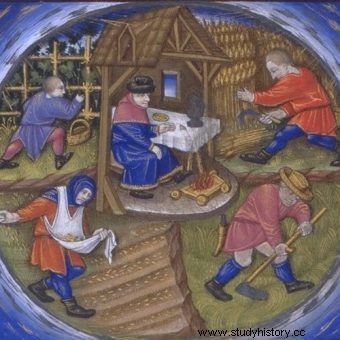

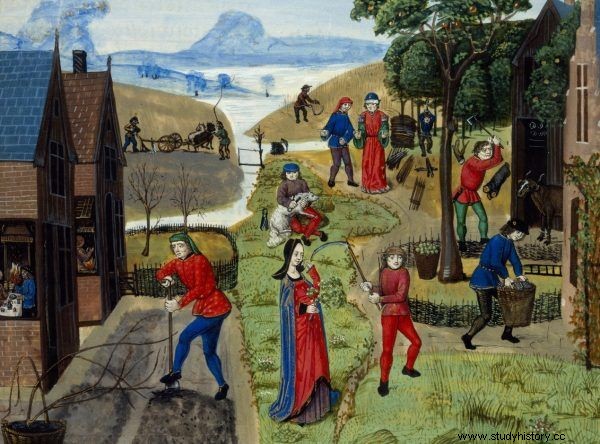

Especially in the countryside, the burden of supporting the aging parents rested on their adult children.

However, in the event that "quarrels and disagreements arise in the future between the parties so that they cannot live together, the said John is to provide Elyas and Christine, or of them who survive the other, a house and a yard where they can live decently" - and moreover specified stocks of grain, peas and beans. In the event of a quarrel with the younger ones, the older couple were also to be entitled to all the furniture, tools and other belongings (...).

Medieval pension system

Children constituted a kind of "capital" for their parents. Contrary to popular belief, the average family in a medieval village was not so numerous at all. At best, it consisted of grandparents, the married eldest son and his wife, unmarried brothers and unmarried sisters of the host who stayed at home, and - rarely - a servant or pair of servants.

Therefore, the burden of supporting both or - more often - one of the parents was not evenly distributed among several descendants. Therefore, it was easiest for the mother or father to stay with the child for old age. (...) Another way of material security for the widow (or widower) in the late years of life after the son took over the farm - although it could be used only by better-off peasants - was to buy a kind of old age or sickness pension in a nearby monastery called "submarine" ( corrody ).

It consisted of a daily ration of bread and beer and a thick soup served by the monastery kitchen. Sometimes you could count on firewood, a room, a servant, new clothes and shoes as well as underwear donated once a year, candles, fodder and a place in a stable.

Some pensions of this kind were modest and included only basic necessities, others much more magnificent - such as the one bought in 1317 at Winchcombe Abbey for a significant amount of one hundred and forty marks by a woman who was to receive two "monastic loaves" of bread each day and one smaller loaf of white flour bread, plus two gallons (nine liters) of monastic beer and the annual allocation of six pigs, two steers, twelve cheeses, hundreds of dried sea fish, a thousand herrings, and finally clothing worth twenty-four shillings.

(…) In some regions, local customs provided much more generous privileges to widows who took over entire farms under joint or lease agreements. (…) Such a widow could then pass the land to her son.

In 1312, when John Bovecheriche ("Churchy") of Cuxham died, he was succeeded by the widow Joan, but she entrusted the house in the village and a plot of land in the fields to her son Elias, living in a cottage that also stood on John's farm. There were times when the son agreed to build a hut for his mother and provide her with a fixed amount of food and clothing.

Sometimes a widow lived in the house, in "her own room at the end of the house," with her son and daughter-in-law, who provided her with food and drink, clothes and shoes. Like agreements in which fathers relinquish farms to their sons, such agreements between mothers and sons were strictly enforced by the judicial authorities operating on the land.

For example, at the Warboys estate, belonging to Ramsey Abbey, in 1334 Stephen the Smith ("The Smith") was fined sixpence because he "did not support his mother as they intended" and jurors ruled that Stephen's mother land should be returned to for life, "and said Stephen cannot have anything from this land, as long as his mother is alive."

Source:

The above text is an excerpt from the book by Frances and Joseph Gies "The Life of a Medieval Woman" , published by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

The title, lead, illustrations with captions, bolds and subtitles come from the editorial office. The text has undergone some basic editing to introduce more frequent paragraph breaks.

Check where to buy "The Life of a Medieval Woman":