The passage of time is not the same as progress. In some areas of life, we are painstakingly getting to what was the standard 5,000 years ago. Like draining the water. And washing your hands after you poop.

"Follow a greater need" or "in two" ... How do we do "it" today? You know! - everyone will think. We go to the toilet, sit on a ceramic shell, do the job, rub paper, drain the water. And, of course, we wash our hands. Simple isn't it?

Well, it is not so obvious. Both the utilization of metabolic effects and the cleanliness of the body have been dealt with in different ways throughout history. What is the basic standard for us today, for the Varsovian of the end of the 19th century was a luxury of the chosen ones.

Do you know who would fit perfectly in your bathroom? A poor Pakistani man from almost five millennia ago .

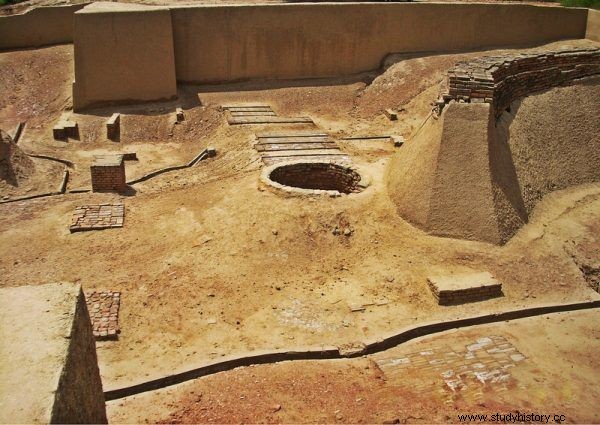

It turns out that in terms of sanitation, we have more in common with the Harappans than with the Poles from 100 years ago. In the photo:an ancient well and probably the ruins of a bathhouse discovered at the archaeological site in Harappa (author:Hassan Nasir, license:CC BY-SA 3.0).

We assume that the farther down the centuries, the less hygiene was of humanity. This is a bug - comments British historian Greg Jenner, author of the book "A Million Years in One Day" .

Great Purgatory Civilization

Long before ordinary Romans rolled up their togas and chatted together in a latrine, representatives of another great, though lesser-known culture enjoyed the benefits of the sewage system.

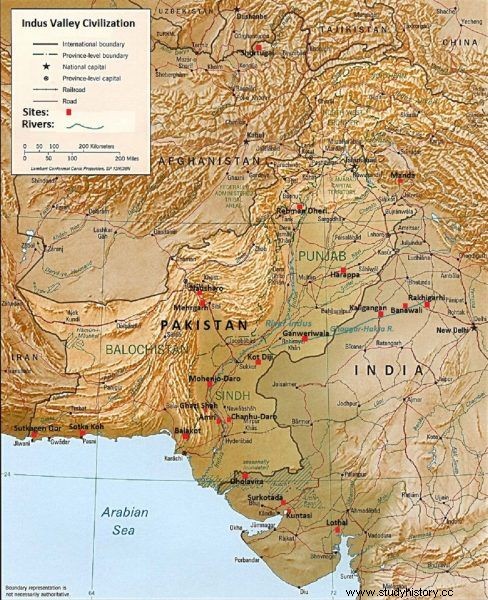

We are talking about the Harappan civilization (also called the Indus Valley Civilization). Its area covers over 800,000 square kilometers, mainly in today's Pakistan.

The first traces of human activity in the region date back to the early Paleolithic times. Stone tools and rock paintings dating back to 400-200,000 BC have been discovered. Settlements where people lived permanently and even raised animals existed here around 5500 BC.

Between 2500 and 1600 BC people in these areas developed a culture whose representatives used writing, built great cities, they drove wheeled vehicles, wore cotton clothes and, last but not least, used real toilets.

About the middle of the third millennium BC, a great civilization developed in the Indus Valley (source:public domain).

Harrapans - so called by archaeologists from the name of the first archaeological site in the Indus Valley - were geeks of cleanliness. Therefore, the effects of metabolism were disposed of from the home through the pipes connecting the toilet to the municipal sewage system.

We already know that extensive sewage networks stretched beneath Harappan cities, built of lime whitewashed bricks. An integrated system of underground pipes and roadside gutters was collecting the dirty water that poured out of the pipes installed in the houses - describes Greg Jenner in his book.

The waste flowed into a network of specially prepared sewage pits. At the end there were wooden grids - cleanable "filters". The liquid, on the other hand, ran into the river. Environmental issues were not a pressing issue at the time…

Meanwhile, in nineteenth-century Warsaw ...

At least in this respect, the ancient cities of the Indus Valley did not differ from the Polish capital of the second half of the 19th century. Perhaps only the Harrapans showed a little more sense of life than the Russians who ruled the Vistula River. As the General-Governor of Warsaw Paweł Kotzebue complained: the waterworks takes water from the Vistula exactly where the sewage flows out .

Sewerage did not appear in Warsaw until 1881 and it is reluctant. Some tenement house owners did not want to pay for a joint system. The idea of moving the privy inside the house was also crooked - as if flying to the privy every morning with a potty was a more convenient solution!

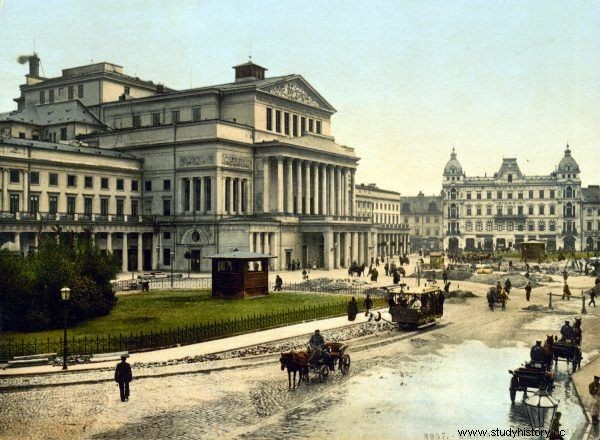

At the end of the 19th century, Warsaw was called the "Paris of the North". Its inhabitants felt they were citizens of the world. And yet, human faeces flowed through the streets (source:public domain).

The demographic boom of the nineteenth century, progressive urbanization, with the simultaneous crampedness of Polish cities, the expansion of which was still often limited by city walls - all this led to a disastrous sanitary situation. People crammed into a small area began to drown in their own excrement.

Running water and toilet bowl

Imagine that you are a Varsovian of the times of fin de siècle. You are overwhelmed by the thought that you live in the "Paris of the North". In the evenings, you go to the theater or the opera, watch world-class stars, and then exchange gossip about social life or discuss art in a cafe or an exclusive restaurant. Only chic.

It is a pity that when you go out on the street, there is a good chance that your sophisticated foot will step into the rapid stream of human feces whose fumes will effectively reduce the smell of your cologne. Before the real sewage system was finally built, sewage in Warsaw flowed through open gutters, most often made of wood. It made the sewers rotten, collapsed, overfilled and clogged.

Meanwhile, the Harappan corresponding to your position did not care at all about similar matters. What's more - his toilet was probably better (and certainly not worse) than that of a Warsaw fairy.

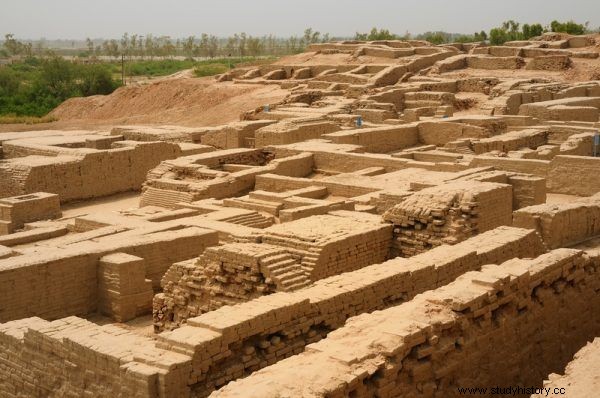

Ruins of Mohenjo Daro - the second great metropolis of the Indus Valley Civilization, next to Harappa (author:Usman.pg, license:CC BY-SA 3.0).

In Harappa or Mohenjo Daro, the rich had a separate bathroom from the toilet . However, they were always close to each other, next to the well - the presence of running water indicated people's high awareness of hygiene. The restroom itself had a seat (Harappans preferred to sit down than squat) and was placed over a ramp leading to the sewage. As we read in the book "A Million Years in One Day":

Even multi-story buildings were connected to the sewage system; Thanks to the ingenious shafts and drainage holes in the floor, the water could be evacuated from any level.

The waste was drained by a network of terracotta pipes. The smell was also taken care of by placing air vents in the walls. The Harappan haciendas were so modern that some even had garbage chutes !

What about the poor?

You probably think: The rich will always position itself. But the poor people were sure to wade up to the ankles….

And here you are wrong. Excavations have shown that in the Harappan culture even the complete hovels of the poor had sanitary facilities - separate bathrooms with a toilet, often connected to the sewage system and with access to running water.

Let's go back to the second half of the 19th century. In Warsaw, if you were not one of the city's social cream, you most likely took care of your needs in a rotting, never cleaned wooden outhouse in the yard of a tenement house. Of course, the latrine was not only for you and your family - it was used by all the local residents.

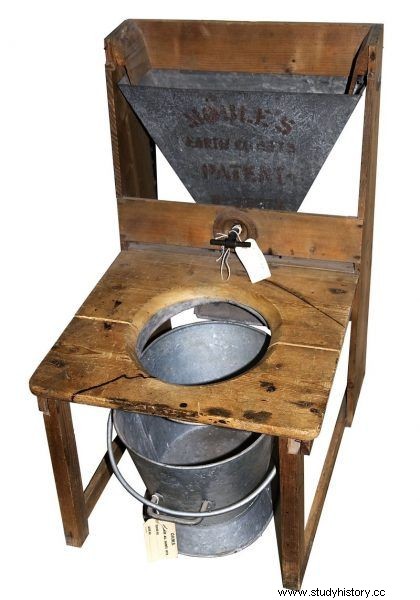

Over the centuries, people have been trying to achieve the highest functionality of toilets. In the photo:Henry Moule's composting toilet, version from 1875 (author:Musphot, license:CC BY-SA 3.0).

Of course, it was impossible to dream about draining the water, not to mention washing the board, because the latrine did not have access to running water. Anyway, hardly anyone had - Marconi's waterworks in Warsaw consumed ten times less water than it was due to the number of inhabitants and their needs . And the situation was improving very, very slowly.

Even in the 1930s, large tenement houses in Warsaw, Łódź and Kraków were deprived of a real toilet. And the proud Sanacja authorities considered the sanitary ideal worthy of the era of progress ... a decent office. Because a man needs nothing more to be happy.

Currently, in Poland (according to data from the Central Statistical Office for 2014), over 95 percent of households are flushed with running water. The situation is improving year by year (still in 2011 it was approx. 90%, and in 2002 - approx. 86%). This is a significant improvement compared to what was around 100 years ago. But is there anything to rejoice over when this was the norm for the Indus Valleyers five thousand years ago?

***

Greg Jenner in the book "A Million Years in One Day. A fascinating story of everyday life ” guides us, step by step, through all our daily activities, showing that each of them has its own hidden meaning and a passionate past. Brushing your teeth with a toothbrush, cereal with milk for breakfast, wearing panties under your pants - these are not the obvious choices. It took centuries for our ancestors to find optimal solutions. Sometimes it was enough to go back to the good old ways from thousands of years ago.

Bibliography:

- Archeological Site of Harappa , World Health Organization [access:February 16, 2016].

- Harappan culture [in:] Library of Congress:Country Studies , 1995, 2014 [access:February 16, 2016].

- Jenner Greg, A million years in one day. Fascinating story of everyday life from cave to global village , crowd. Julita Mastalerz, Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, Warsaw 2016.

- Pittman Holly, Art of the Bronze Age. Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia and the Indus Valley , The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984.

- Ragland Johnny, The Hidden Room. A Short History of the "Privy" , Kingston University, London 2004.

- Situation of households in 2014 in the light of the results of the household budget survey , GUS, Warsaw May 26, 2015.

- Tracking Down the Roots of Our Sanitary Sewers , "SewerHistory.org" [access:February 16, 2016].

- Results of the 2011 National Census of Population and Housing , GUS [access:February 16, 2016].

- From the history of the Warsaw sewage system , "Woda.edu.pl" [access:February 16, 2016].

- Żyromski Marek, 19th-century Polish family , "Annals of Family Sociology" No. 12, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań 2002.