The Battle of Marathon pitted the Athenians against the Persians in 490 BC. To extend the hegemony of the Persian Empire to the Mediterranean, King Darius I launched an attack against mainland Greece in 490 BC. AD Led by Mithridates, the Athenian army manages to defeat the Persians on the very site of their landing, at Marathon. This great victory put an end to the first Greco-Persian War and consecrated the power of Athens. It gave birth to a famous foot race, whose chosen distance is that which the Greek soldiers covered at a run to go from the beach of Marathon to Athens in order to announce the victory of the Greek oplites over the Persian army. .

The Battle of Marathon pitted the Athenians against the Persians in 490 BC. To extend the hegemony of the Persian Empire to the Mediterranean, King Darius I launched an attack against mainland Greece in 490 BC. AD Led by Mithridates, the Athenian army manages to defeat the Persians on the very site of their landing, at Marathon. This great victory put an end to the first Greco-Persian War and consecrated the power of Athens. It gave birth to a famous foot race, whose chosen distance is that which the Greek soldiers covered at a run to go from the beach of Marathon to Athens in order to announce the victory of the Greek oplites over the Persian army. .

At the origin of the Battle of Marathon:the Greco-Persian rivalry

In the second half of the 6th century BC, the Persian Empire (from the Greek "Persis", originally designating the region located south of Iran) extends from the western borders of India to Egypt, encompassing Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and Syria-Phoenicia. The empire was then governed by Emperor Darius I (521-486 BC), third ruler of the Achaemenid dynasty founded by Cyrus the Great in 559 BC. The Greeks, although disunited by the rivalry between the great cities, are the only neighboring people still unsubdued, with the exception of the Greek cities located in Asia Minor. It was in this region that in 499 BC. BC, the revolt of the Greek islands of Ionia (encouraged by the recent defeat of Darius before the Scythian nomads), harshly repressed, ignites the powder.

The Athenians, whom the city of Miletus had called for help, support the revolt of the Ionians. They send 20 boats which land in Asia Minor, while the city of Eretria sends five. Strengthened by this support, the Ionians attacked the Persian city of Sardes, capital of the province of Satrapie, by surprise, which they set on fire. The Persians intervene, defeating the Ionians at Ephesus, retaking Cyprus and destroying the port of Miletus in 494 BC. J.-C.

The destruction of Sardis aroused such resentment in Darius that before each of his meals, a servant must now repeat to him “King, remember the Athenians”…

The First Persian War

Thus begins the first Persian war, which opposes the Persians (the Medes) to the Greeks. Wanting revenge on Athens, Darius opened hostilities in 492 BC. J.-C., by sending both a large army commanded by the Persian general Mardonios and a fleet from Cilicia. The army is responsible for seizing Athens and Eretria, after passing through Thrace already conquered.

Thus begins the first Persian war, which opposes the Persians (the Medes) to the Greeks. Wanting revenge on Athens, Darius opened hostilities in 492 BC. J.-C., by sending both a large army commanded by the Persian general Mardonios and a fleet from Cilicia. The army is responsible for seizing Athens and Eretria, after passing through Thrace already conquered.

But as the Persians are put in trouble by the Thracians, the Persian fleet is caught in a storm off Mount Athos. 20,000 men are drowned and 300 ships destroyed, almost the entire fleet. Faced with this disaster, the Persian offensive was abandoned, although Mardonios succeeded in subjugating Thrace and Macedonia.

But the so-called "King of Kings" does not admit defeat. In 491 BC. J. - C., Darius sends ambassadors charged to ask “the ground and the water”, ie their submission and their allegiance, with the Persian sovereign. Athens, Plataea and Sparta having refused, Darius decides to launch a military expedition again and raises a new fleet.

The Persian Invasion

At the beginning of September 490 BC. AD, it crosses the Aegean Sea and sails to the island of Euboea to take the city of Eretria, which had participated in the revolt of the Ionians. The city is mercilessly destroyed and its inhabitants are reduced to slavery. Once this package is accomplished, the Persian fleet takes the direction of Attica and manages to land in the bay of Marathon in order to take revenge on Athens.

The Persians number around 20,000 men, under the orders of the Mede general Datis and General Artaphene, nephew of Darius. For their part, the Greeks only gathered an army of 10,000 men, led by the strategist Miltiades and essentially composed of Athenians. The latter only found Plataea, located in Boeotia, to support them, which sent them a thousand men. Knowing the fearsome reputation of the Persians, Sparta invoked festivals in honor of the god Apollo to refrain from participating in combat without appearing to officially refuse.

The Battle of Marathon

The two belligerents meet about forty kilometers northeast of Athens, in the plain of Marathon, 10 kilometers long and 3 kilometers deep. Miltiades immediately positioned men on the surrounding heights to prevent the Persians from advancing towards Athens.

The two armies do not clash immediately. They take the time to observe each other, to try to guess their mutual intentions and position their troops as favorably as possible. General Datis is convinced that Sparta will soon send reinforcements to the Athenians. The Persian leader then decided to attack both by land and by sea, and had part of his troops re-embark to bypass Attica towards the port of Athens, Phaleron. The goal is to attack the city weakened by the absence of the fighters who remained in Marathon to face the rest of the Persian army.

Miltiades takes this opportunity to compensate for his numerical inferiority. He placed the Athenian troops on a line equivalent to that of the enemy, i.e. 1,600 meters. But when he launches the offensive, Miltiades pretends that he is attacking from the front. Hesitating on how to engage in combat, the Persians suddenly saw the Greek hoplites (foot soldiers) rushing towards them and advancing faster and faster with long pikes and large shields, from a distance of 1,500 meters. The Persians barely have time to use their many archers and rush in turn straight ahead, managing to pierce the Athenian center. They then sink into the trap set for them.

Miltiades takes this opportunity to compensate for his numerical inferiority. He placed the Athenian troops on a line equivalent to that of the enemy, i.e. 1,600 meters. But when he launches the offensive, Miltiades pretends that he is attacking from the front. Hesitating on how to engage in combat, the Persians suddenly saw the Greek hoplites (foot soldiers) rushing towards them and advancing faster and faster with long pikes and large shields, from a distance of 1,500 meters. The Persians barely have time to use their many archers and rush in turn straight ahead, managing to pierce the Athenian center. They then sink into the trap set for them.

Indeed, the Persians do not know that the Athenians did not place their main forces in the center, but on their wings, so as to envelop the enemy from the sides:the wings include eight rows of hoplites, while the center has only four.

As Miltiades predicted, the Persians are caught off guard by the power of the Greek wing attack. They do not have time to bring in their cavalry or their archers, while the Greek phalanxes fall back around them. Completely overwhelmed, the Persians placed on the wings prefer to abandon the battle and the Greeks, letting them flee, turn against the Persians placed in the center, who are surrounded. Unlike the hoplites, the Persians are not protected by a cuirass and are routed. They then fled in the direction of their ships, pursued by the Greeks. The Battle of Marathon, which ends around 9 a.m., lasted three hours.

But the Persians, although heavily beaten at Marathon, did not disarm and the survivors of the battle left to join the forces already sent in the direction of Phaleron.

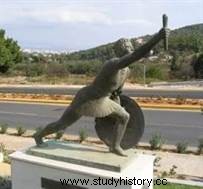

The race to Athens, the origin of the marathon

Legend has it that after the battle, an Athenian soldier was tasked with informing Athens as soon as possible of the victory at Marathon. The messenger, Philippides, would then have run 42 kilometers in four hours without stopping and would have died of exhaustion on arrival, just after transmitting his message. In memory of this feat, the modern Olympic Games organize a 42.195 kilometer race called the “marathon”.

In fact, Miltiades made his men cover the same distance, not by running but by forced march to arrive on time. When the Persians reach the outskirts of Phaleron, the day after the battle of Marathon, they realize that the fight is lost in advance, because the winners of Marathon have preceded them. In addition, the Lacedaemonians, the inhabitants of Sparta whom the Persian defeat convinced to intervene, are added this time to the Athenians all together.

In fact, Miltiades made his men cover the same distance, not by running but by forced march to arrive on time. When the Persians reach the outskirts of Phaleron, the day after the battle of Marathon, they realize that the fight is lost in advance, because the winners of Marathon have preceded them. In addition, the Lacedaemonians, the inhabitants of Sparta whom the Persian defeat convinced to intervene, are added this time to the Athenians all together.

A decisive victory

For the first time, the mighty empire of Darius is defeated, and in a particularly humiliating way since the Persians, although twice as numerous as their adversaries, have lost approximately 6,400 men, against 192 casualties on the Athenian side. This is the end of the first Persian War. The fighters who died during the battle were buried in the plain of Marathon and today you can still find the tumulus under which they rest, making this place probably the oldest of the military cemeteries.

Marathon's victory, though unspectacular, shattered the Persians' reputation for invincibility and gave the Athenians considerable prestige, reinforcing their attachment to the freedom of their city and to their role as citizens. It also highlights the superiority of the hoplites, until a new victory, naval this time, of the Greeks over the Persians at Salamis, in 480 BC. This distinguishes the Athenian maritime power to the detriment of its land power.

Bibliography

- The Battle of Marathon, by Patrice Brun. Larousse, 2009.

- The Battle of Marathon:the legendary episode at the end of the First Persian War, by Delphine Dumont. 50 Minutes, 2013.

- The Persian Wars:499-449 BC. AD, by Peter Green. Text, 2012.