The Prussian cavalry at the beginning of the 18th century. and until about 1742, it followed obsolete tactics. The Prussian horsemen moved slowly against the enemy, so as to maintain their cohesion as much as possible, halting their movement several times to charge against him. When they were attacked by cavalry, they did not, in many cases, counter-charge against the opponents, but waited motionless for the charge, ready to repel it by the use of fire.

But this, as is easily perceived, deprived them of the greatest advantage of the cavalry, the striking power. Even against enemy infantry, they moved slowly, in a light skirmish, and only charged at him when they got within about 60 paces - about 45 m It is understandable that from such a distance the horses did not have time to develop their maximum possible speed at the moment of contact.

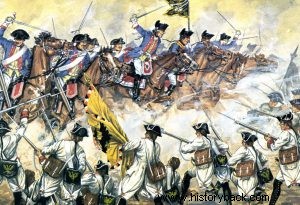

The slow advance of the Prussian cavalry gave the enemy infantry all the necessary time to prepare their reaction, thus neutralizing the psychological effect of the cavalry attack. After the cooldown at the Battle of Mollwitz, where the Prussian cavalry fled in disgrace, Frederick implemented an intensive program of upgrading his cavalry's fighting ability. The result was that the "archaic" Prussian cavalry turned into a deadly war machine, the most perfect cavalry corps in Europe.

Characteristic of the level of training of the Prussian horsemen was the fact that during exercises 40 horse companies advanced, at a gallop, without gaps between the companies, without losing their cohesion. Just the sight of 6,000 horsemen moving like an unbroken solid wall at great speed was capable of awe-inspiring the onlookers. Frederick did not hide his admiration.

It is a fact that the outcome success of cavalry operations was directly linked to the speed, momentum and cohesion of the cavalry unit that carried them out. The success of the cavalry depended on the psychological effect, on the fear it caused in the opponent. Usually one of the two segments would flee moments before or shortly after contact.

The vast majority of casualties were inflicted by the victor on the vanquished in the pursuit phase. It was therefore a factor of the utmost importance to maintain the cohesion of a cavalry division as well as its ability to regroup rapidly after a successful action. The secret of the success of the Prussian horsemen was NOT the ability of each, on a personal level, to emerge victorious from a series of personal duels with opponents. It was the collective action that decided the result and above all it was the speed of execution of the attack that decided the winner.

Ordinary doctrine…

The Prussian tactical doctrine of the use of cavalry is summed up in just two words:rapid charge. Cavalry was by no means to be turned into a set of individual duels, where "the officer would be of no more value than the common soldier". Thanks to the rapid attack, always at a fast gallop, which started at a great distance from the enemy, the Prussian fighters had a clear tactical advantage over their opponents, while also boosting their morale.

On the contrary, the morale of the opponents was falling significantly. "I ordered the islands to attack at a fast gallop because fear compels even the cowards to move with the other men – they know that if they hesitate they will be crushed by the rest of the island. My intention is to break the enemy with the speed of our attack, before the divisions even make contact. Officers are worth no more than ordinary horsemen, during a skirmish and the order and cohesion of the division is lost."

With these words Frederick himself simply described the new regular doctrine. Thanks to their excellent training, the Prussian horsemen were able to achieve amazing attack rates. Until 1748 the advance started from a distance of 700 meters from the enemy. Of these, 300 meters were covered by trotting and 400 by galloping. Two years later the starting distance of the raid increased to 1,200 meters (300 at a trot, 400 at a canter and the last 500 at top speed), to reach 1,800 m in 1755!

…and application

It is easy to see that the opponents had only a few seconds at their disposal to win or die. The Austrian horsemen, by comparison, cruised at full speed in the last 30 m just before contact. However, attacks against infantry divisions that maintained their cohesion were usually avoided.

But as soon as the slightest disorder was noticed in the enemy line, the horsemen rushed to take advantage of it. This happened at Hohenfriedberg (1745) when the 5th Prussian Dragoon Regiment saw a gap in the Austrian line. He immediately attacked with speed so as not to allow the opponent to close the rift.

The result was disastrous for the Austrians, 20 battalions of their line swept away by the Prussian advance, thousands of men killed or wounded, – many of them trampled among themselves in their panic – and 2,500 captured, by a single cavalry regiment !

But there were two other factors that made the success of the Prussian cavalry extremely likely. The first had to do with the use of "phalanx" type formations by the cavalry and the second with the use of short lengths of support straps on the horsemen's stirrups. Deep formations had disappeared from cavalry campaign manuals as early as the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648).

Along with the thinning of the infantry lines, from 30 to 10 and eventually to three and the depth of the cavalry formations dropped from 10 yoke to three or sometimes even two. The raid in a phalanx formation, in a double line formation six yoke deep essentially, carried out by coordinated infantry, so that the great depth ensures the replacement of the losses of the first scales.

The famous raid of the 5th Dragoons on Hohenfriedberg executed in phalanx formation. In another case or raid, in phalanx formation a regiment of dragoons – 5 iles – was supported by 10 iles of hussars, in line formation – five on each side of the dragoons.

This hybrid "mixed rank" cavalry formation, until recently considered the invention of French generals of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, was purely Prussian in conception and application. This particular attack model was used by the Prussians in numerous battles.

At Chondorf (1758) in particular, used extensively by General von Seidlitz – the best cavalry commander in Europe at the time – against the "squares" of the Russian infantry. As for the short length of the stirrup straps, it particularly helped the rider to stand up on the saddle and deliver a powerful crushing blow to the opponent.

Prussian Regiment of Dragoons crushes the Austrians.

Prussian dragoons of the 5th Regiment present Frederick with flags captured by the enemy.

Prussian cuirassiers charge.