The use of the pilum in the Italian peninsula it began very early, the first specimens are documented in the Samnium region in the 8th century BC. C. (Roggiano Gravina specimens). From the 5th century BC. C. we also document it in Lucania (specimens from Metaponto, Paestum...) and in Etruria (specimen from Vulci). In clearly Roman hands they are not documented until the 3rd century BC. C. (Talamonaccio), although in all probability they used them from earlier dates. It soon became one of the main ingredients of the manipulative army's own form of combat, and some of its earliest examples have appeared in the Iberian Peninsula, such as on the battlefield of Cerro de las Albahacas/Santo Tomé, Jaen) , scene of the Battle of Baecula. Although it was a weapon that evolved a lot throughout its long history, in essence it was an iron rod ending in a pyramidal point, attached to a wooden handle, with dimensions that ranged between one and a half meters and two meters, as well as a weight between two and five kilos. The stack number used by each soldier has been widely discussed due to its reduced range, barely 30 m, considering that the members of the first ranks should go with only one, while the legionnaires of the back ranks would go with a second pilum .

One of the most widespread myths regarding this weapon is that it had a specific design that was intended to bend when it hits enemy shields, rendering them useless. While it is true that the pilum it could bend when hitting an especially hard object, this was not due to a specific or intentional design but because they were made of relatively ductile mild steel (without carbonating). What truly allowed the pilum make enemy shields useless -as experimental archeology has shown that it could penetrate up to 3 cm of wood- was its pyramidal head:once pierced, the wood tends to swell, so it is difficult for the head, larger than the shaft, to be extracted.

While the pilum was a weapon of proven effectiveness against masses of infantry, the expansion of the Roman borders brought new challenges, such as the massive presence of cavalry on the eastern battlefields, which led to the development of a new weapon:the lance, increasing from the 1st century AD. as its use expands to many units and not just cavalry.

Despite the infinity of types and terms, we can conclude that it consisted of a wrought iron point fixed with a tubular handle to a wooden till, with a metal ferrule at the opposite end. Originally its design was intended to serve both as a cavalry throwing weapon and as a rush weapon. From the 1st century AD the auxiliary infantry began to use it as well, with identical use, wielding one and carrying two smaller and lighter ones behind the shield. Throughout the 2nd and 3rd century the lances remained the main weapon of the auxiliary infantry (beneficiarii , frumentarii , speculators ), up to five appearing in the hands of an auxiliary soldier on a funerary stela from this period; while the cavalry adopted the contus , a heavy spear of Sarmatian origin that, due to its size, had to be used with both hands at the same time.

From the end of the 3rd century the lances It stopped being used as a throwing weapon and increased considerably in size. Its use became popular among specific units beyond the auxiliary ones, appearing the term lanciarii to refer to those contingents that used it.

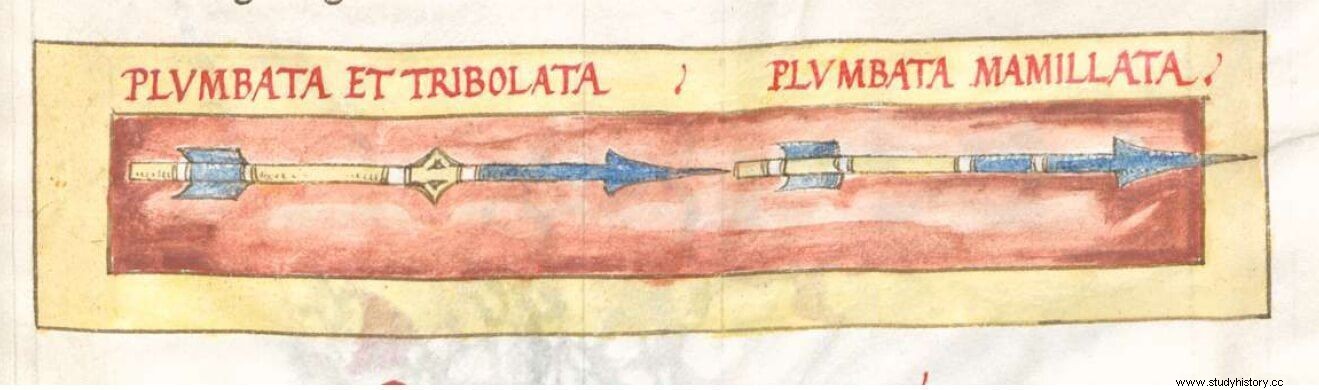

The great innovation from the end of the third century was the plumbata (diminutive of hasta plumbata :leaded spear) or martiobarbulus (Mars dart) which consisted of a dart, or rather an arrow, with a lead ballast that gave it weight and allowed it to be thrown by hand and pierce enemy shields. According to ancient sources, the Epitoma rei militaris of Vegetius and the anonymous De Rebus Bellicis fundamentally, as well as various archaeological finds, the main type of this projectile was the so-called plumbata mamillata (leaded with breasts), which consisted of a pointed point of circular section with a bulbous lead ballast under it, mounted on a shaft up to 50 cm long and finished off with fins at the opposite end. Another type, of which no archaeological evidence has been found, was the plumbata et tribolata , which featured spikes in the lead ballast to hurt any careless enemy soldiers who stepped on it when it fell to the ground.

Each soldier was to carry up to five of these projectiles on the inside face of his shield, remaining close at hand to be launched during the charge or while taking a defensive position, at which point they were launched by members of the third rank. The plumbata it was launched with one hand and according to the latest experimental archeology research, conducted with replicas of various sizes, a range of up to 60 m could be achieved. This distance agrees with Vegetius's comment that soldiers throwing the plumbata they played the role of archers because "they managed to hurt the enemy before they entered the range of conventional projectiles."

In conclusion, the study of the evolution of the Roman weapons of the pilum to the plumbata shows how the Roman army in the late Empire did not decline in quality; but, although all the weapons mentioned enjoyed a certain continuity, the Roman panoply remained immersed in a continuous process of adaptation to the new military scenarios and the new challenges imposed by the new enemies. While the pilum It was a weapon of great importance for close combat against large masses of infantry, it proved to be a barely effective weapon against the armored Persian and Goth horsemen. The lances was therefore the natural response to the need to engage enemy horsemen while being able to maintain a minimum range between thrown weapons, which would prove equally inappropriate against the fearsome horse archers that since the end of the 19th century third century populated the eastern borders of Rome. Therefore, it was necessary to invent a weapon that would give the Roman infantrymen a hitherto unprecedented range, but at the same time would not prevent the use of the scutum nor prevent quickly unsheathing the sword:the plumbata , with a range twice that of the pilum or the lancer and whose simple use was the perfect answer.

Bibliography

Bishop, M.C., Coulston, J.C.N. (2016):Roman military equipment . Madrid:Awake Ferro Editions.

García Jiménez, G. (2013):«The pilum Roman in the Second Punic War» in Desperta Ferro Antigua y Medieval no.17, pgs. 44-45,

Southern, P., Dixon, K. (2018):The Roman Army of the Later Empire . Madrid:Awake Ferro Editions.

Quesada Sanz, F. (2003) "The Roman legionnaire at the time of the Punic Wars:Forms of individual combat, small unit tactics and Hispanic influences" in Space, Time and Form , Series II 16, p. 163-196.