During the Seven Years War, the Prussian Army fielded 49 line infantry regiments of each type (musketeers and fusiliers). Of the soldiers that made up the infantry regiments, at least 1/3 were foreign mercenaries, coming mainly from the small German states neighboring Prussia.

But there were others who came from France, Switzerland, Ireland, Italy, and even from the Ottoman Empire. Most foreigners served in the younger regiments of fusiliers and there were almost entire regiments that were entirely mercenary. Even the highest officers of the Prussian Army were foreigners, the most famous of whom was the French Fouche, or the Irish Keith.

Naturally, the connecting link of this motley military machine was none other than harsh discipline. According to Frederick the men were to fear their officers more than the enemy. Despite the harsh measures, however, desertions were frequent, especially among certain categories of mercenaries.

But the strange thing was that this serious offense, the heaviest of the military penal code, was not punished with the ultimate punishment except in exceptional cases. The explanation for this paradox is however simple. The army at that time was professional and therefore expensive to build and maintain.

Each trained soldier was a state capital whose loss left an irreplaceable void. The time and money spent on his education was wasted . Therefore, the solution of the executive branch was avoided. Frederick's dialogue with a deserted soldier who was captured has been preserved.

The king calmly asked the soldier why he deserted and when he did not answer, Frederick told him:“I know. You left because you thought we were losing. So listen to this, tomorrow we will go to battle and if we are defeated then come and desert together!

So instead of the death penalty they preferred another, barbaric punishment, from which the soldier usually came out alive. According to the gravity of the offense, the company or battalion of the punished soldier was lined up, in two yokes, facing each other.

The offender was then forced to run between the two yokes of his colleagues, who beat him with wooden sticks. If the offender fell from the blows, it was at the discretion of the chief officer to allow the men to flog him to death or – as was usually done – to order a halt to the flogging.

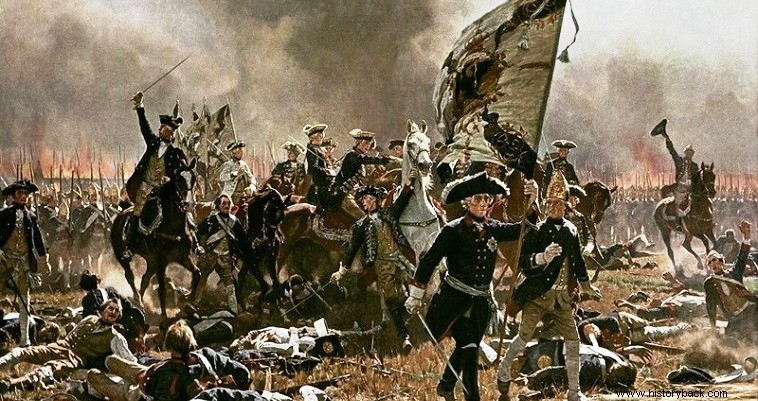

Despite these inhumane methods, heavy losses and shortages of food and supplies, the native Prussians rarely left the lines. Even the mercenaries, however, in many cases honored the Prussian flags more than that.

There are many examples of blind devotion, to the point of death in duty and especially in Frederick himself. In the battle of Mollwitz (1741) there was a French mercenary who, by self-sacrifice, saved Frederick's life.

It was the Irishmen of the 19th Regiment who sacrificed up to one at the battle of Hokirk (1758), to enable their colleagues to withdraw, after the surprise attack of the Austrians. The 2/19 Battalion stubbornly defended the village church and when they ran out of ammunition they charged with their lance against the enemy!

Only discipline and a strong spirit of unity formed the connecting link of the army, and yet this link was so strong.