The battle of Rosbach is a tactical masterpiece of Frederick the Great and the most classic application of maneuver on interior lines. Although the Prussian forces were dramatically outnumbered, they achieved an overwhelming victory, despite the logic of numbers.

The Seven Years' War (1756-63) could be characterized as a continuation of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). All the major European powers participated in it and the conflicts extended beyond the Old Continent to America and India. The main cause of the outbreak of the war, however, was none other than Austria's intention to recapture the rich province of Silesia that it lost during the previous war.

Austria was eventually joined by Russia, France, most of the small German states and Sweden. Prussia, with sole allies Britain and the German states of Hanover, Braunschweig and Hesse Kassel, bore the brunt of the struggle in the European theater of operations against rival armies.

War broke out in 1756. After a series of maneuvers and battles, in December 1757, a small Prussian army under Frederick II the Great faced at least twice as many French and German armies at Rosbach.

The opposing forces

In the battle of Rosbach, on the Prussian side, 27 infantry battalions, with 16,600 men, 45 cavalry companies with 5,400 men and about 500 artillerymen, totaling 22,500 men, took part. The command was exercised by Frederick himself, with the Irish-born General Keith second in command.

The cavalry, organized into two brigades, was commanded by the famous lieutenant general at the time, Friedrich Wilhelm von Seidlitz , the best cavalry commander of the time, who also directly commanded the first cavalry brigade. This brigade was made up of the 7th Breastplate Regiment (ST) with five regiments, the 3rd Breastplate Regiment, also with 5 regiments and the 4th Dragoon Regiment (SD), also with five regiments.

The second brigade, under Major-General Baron von Schenneich, extended the famous 13th Division of the Guard, with three islands, the 10th Division of the Gen d'Arms, with five islands, the 8th Division, with five islands, and the 3rd Division, also with five islands. The 12 hussar companies of the 1st and 7th Hussar Regiments (SO) were the reserve.

The infantry was organized into three divisions. The first two were placed under the command of von Desschau. The first, commanded by von Braunschweig, had two brigades, nine battalions in total, including the five elite.

The second division under Lieutenant-General Prince Heinrich, brother of King Frederick and an excellent soldier – perhaps Frederick's best – also had two brigades, with 11 battalions, three of them elite and two others of the 13th Infantry Regiment (Lightning and Lightning Regiment ).

The third division under Lieut.-General von Forcade extended six battalions, the two elite. Also at Frederick's immediate disposal was the Mayer light infantry battalion. In addition to the supporting guns, Frederick's force had 25 12 pdr field guns.

The Prussian Army was considered and was the best in Europe, at that time, with Prussia characterized, not unjustly, as the new Sparta . The infantry were highly trained and could fire at twice the rate of all other European armies of the time. And the cavalry was trained to launch organized attacks, ignoring enemy fire, with the aim of causing a psychological effect on the enemy, so as to break him up and suppress him.

On the other hand the allied army was a mixed force with the quality of its units ranging from excellent to abysmal. The allied army was structured into five corps.

The first consisted of an Austrian cuirassier brigade, with seven islands, an Imperial German (Reich) cavalry brigade, under Prince von Hohenzollern, with two SS (seven islands) and one SD (two islands). The first corps still had two French infantry divisions, each with two brigades and eight battalions in all, and a French cavalry division, with two brigades, each with three regiments of two hils. The body also had 33 cannons.

The Second Corps also had an Austrian cuirassier brigade (seven isles), an Imperial cavalry brigade (one SS, one SD, with a total of 10 isles) and two French infantry divisions, each of two brigades with eight battalions per division. The second of these divisions, under the Swiss von Bauer, extended eight elite Swiss battalions.

The third corps under Lieutenant-General de Broglie extended two cavalry brigades with 10 battalions in total and two infantry brigades with eight battalions in all.

The fourth corps, under the Prince of Hesse Darmstadt extended 11 battalions of Imperial infantry with 12 guns. Of these battalions three, two from Würzburg and one from Hesse Darmstadt were well trained. The remaining four were considered of average quality and the remaining four as having no combat value.

The fifth corps, under Lieutenant-General Comte de St. Germain, fielded 16 French and three Austrian cavalry regiments, eight French infantry battalions and two Austrian light infantry regiments.

Maneuvers

The French marshal Prince Soubis had advanced north-east into Saxony, reaching the river Saale, covering the west bank and capturing the small towns of Weissenfels and Merzeburg where there were bridges and controlled the passage of the river and the city of Halle, further north, where there was also a bridge. Subis had himself taken over the guarding of the bridge at Merzeburg, assigning to Broly the guarding of the bridge at Hali and to Hildburghausen the defense of Weissenfels.

Frederick decided to try to cross the river in two places. He himself with the bulk of his forces would move against the Imperials at Weissefels, while Keith would try to cross to Merzenburg.

On 31 October Frederick arrived at Weissenfels and at first light ordered his grenadiers and the light infantry of the Mayer Battalion to attack the town which was guarded by 4,000 Imperial and about 1,500 French troops. This force was enough to hold the fortified city for some time, at least.

However, surprised by the Prussian attack, they fled, managing to destroy the bridge over the Saale river. Most of the garrison escaped, except for about 300 men who were captured.

Frederick entered the city and reached the ruined bridge. A French artillery was positioned opposite. The head of the artillery then asked for permission from the local commander, Duke de Crigault, to shoot at the Prussian king and his entourage. But the noble de Crigault replied that it was impermissible to shoot at the sept face of a king. He would soon bitterly regret his excessive kindness.

Further north, Mezenburg, the allies had also destroyed the bridge before Keith's force and retreated. At both points, Frederick and Keith began to look for a passage in the river, swollen by the autumn rains.

This was not accomplished until November 3, when the Prussian forces crossed the river, those under Frederick by a ford they discovered, those under Keith by a pontoon they constructed. Late in the afternoon of November 3, the two Prussian forces joined and deployed between the villages of Bedra and Rosbach, the following day.

Frederick, taking advantage of the full moon, moved forward to reconnoitre the enemy's positions, and the allied army, retreating from the west bank of the Saale, was deployed on the heights of Shortau, in a suitable position for defense.

The Prussian king had information that the allied army had a strength of 60,000 men. Perhaps this information was deliberately leaked by his opponents. However, as, due to the night, he could not ascertain the reality, Frederick decided to wait for dawn before taking action.

Lightning and lightning in the field of glory

As dawn broke on the 5th of November, a frosty but broad daylight Saturday, Mayr's Light Battalion, which had deployed scouting parties along the Prussian position, reported that a strong enemy force, numbering eight battalions and several islands, had advanced against them in offensive formation. . This body, under St. Germain, however, did not intend to attack.

The previous evening the allied commanders, having taken Frederick's hesitation to attack them directly on the Shortau Heights as a sign of weakness, had decided, at the suggestion of Hildburghausen, to execute a wide flanking maneuver, moving against the Prussian left flank, with the aim of encircling the Prussian army and, if possible, recovering the line of the Saale river. Such a thing would have resulted in the entrapment and destruction of Frederick's small army.

The plan could be excellent if it took into account key parameters such as the quality of the allied forces, the corresponding quality of the Prussian forces and above all Frederick's ability to react. There was only one way to succeed, speed. Only if the allied army moved quickly could the plan succeed. Otherwise the Prussians occupying higher ground would have a full view of their movements and could hit them.

However, speed was a characteristic that the allied army did not possess. Loaded with useless baggage, with men not well trained and consequently unable to execute a short course with a full load, the maneuver was doomed in advance.

However hope dies of late and so the allied command made the fatal decision. At 08.00 Frederick, having been informed that something was happening in the opposing camp by his snipers, rushed to the line of guards to see for himself what it was all about. Frederick, realizing that St. Germain's force was only for show and had no intention of attacking, returned to the inn where he had set up his headquarters, quietly.

Around midday the allied army finally started to execute the supercanon maneuver, moving in parallel phalanxes of march, led by the Austrian and Imperial cavalry, but without sending reconnaissance units forward. An officer of the Imperial Army rightly commented on the plan, saying:"No general would allow himself to be overcharged with his eyes open, and the King of Prussia is one of those who can hardly be taken by surprise." strong>

The allied army initially turned to the southwest, pretending to retreat. But soon it changed direction and turned towards the northeast. A Prussian captain, Friedrich Wilhelm Gaudí, who was observing the enemy's movements perceived the movement of the allied army and hurried to inform Frederick, who at the time was dining with his generals. The time was 14.00 when Gaudí burst, literally, into the room where Frederick was having lunch, ignoring all rules of good behavior.

Frederick, disturbed by the invasion, demanded to know the purpose of so much violence. When he heard the captain's report he hurried to see for himself what was happening. Now convinced of the information, he immediately ordered his men to get ready. At the same time Frederick called his generals and drew up his plans. With his quick perception Frederick had already grasped the plan of battle and destruction of the opposing army.

Behind the village of Rosbach stretched the hill of Janus. Frederick decided to take advantage of him, executing another maneuver on internal lines, this time on a tactical scale. So he ordered his cavalry, under Zeidlich, to move north of this hill, which would allow him to move unseen by the enemy and deploy before the front of the opposing phalanxes.

The infantry and artillery would follow the same route, parallel to the cavalry, but at the appropriate moment would be deployed for battle on the ridge of the hill, with the intention of the infantry falling on the flank of the opposing phalanx, and the artillery, having a wide field of fire, will cause the greatest possible losses and confusion to the enemy.

He left behind him only the Maire Battalion and a few hussars, to mislead St. Germain. Zeidlich mounted his horse and turning to his officers said to them:Gentlemen, I obey the king and you obey me. Follow me.” Saying this he galloped forward followed by his regiments, with a total of 38 iles, 23 cuirassiers, 10 dragoons and five hussars.

In the meantime the allied army continued its movement. 14 Austrian and nine Imperial islands moved as a vanguard. This mass of cavalry moved at a distance of about 1,500 m in front of the allied phalanxes. But suddenly the thunder of the cannon was heard.

Colonel Moller's 18 guns, having received clear orders from Frederick himself, had been deployed on top of the Janus hill and had opened rapid fire against the dense allied phalanxes, causing a rather unpleasant surprise to command and men.

Prussian elite, grenadier.

It was approaching 15.15 when the first shots were fired which signaled the start of the Battle of Rosbach. The artillery fire was also the cue for Zeidlich to turn his flanks to the right and move against the Allied vanguard, as planned.

Zeidlich deployed his cavalry in the area between the slopes of Janus Hill and the village of Reichardwerben. In front of him was the enemy vanguard at a distance of about 750 m. Zeidlich calmly reorganized his forces and deployed them for battle, in two lines, with 20 men in the first and 18 in the second. When everything was ready he ordered "Forward" and took the lead himself with sword in hand.

The Prussian advance was launched with order, as well as momentum. The first to bear the brunt of the Prussian attack were the Austrian horsemen, who, for some minutes, managed to hold out. The nine imperial isles and two isles of Austrian hussars immediately rushed to their aid, while Soubis also ordered the French cavalry to rush to their reinforcements. However, despite being reinforced with 24 French islands, the excellent Prussian cavalry, excellently led by von Seidlitz himself, managed to break through the lines of the enemy cavalry.

Soubis tried to reverse the situation, and putting himself at the head of 16 French ships, marched against the Prussians. Against him, however, Zeidlich threw the 18 islands of his second line, crushing the French cavalry.

After a fierce horse fight that lasted for about 30 minutes, the allied cavalry had broken up with their regiments having lost all organic ties and had become an unmanageable mass of men, who, seeing everywhere the indefatigable Prussian horsemen, thought only of how to save their lives.

Although Subis tried to reorganize them, between the villages of Reichardverben and Tageverben, a new advance scattered it for good, sending it into disorderly flight.

Zeidlich, as an excellent commander, did not allow his cavalry to pursue their fleeing opponents, but reorganized his isles and deployed them south-west of the village of Tageverben, expecting to support the friendly infantry which, moving in echelons to the left, had descended from Janus Hill and had formed a front west of the village of Reichardwerben.

The cavalry moved to the left of the infantry, covering it, while Moller's guns were also placed on a small hill on the outskirts of the village, from where they could fire above the lines of the friendly infantry.

Seeing the development, Hildburghausen turned to Soubis and told him, fearfully:"We are lost." The Frenchman contented himself with answering:"Courage." At the same time Soubis ordered the eight battalions of the Piedmont and Maygi regiments to deploy against the Prussian battalions. At the same time he ordered his other battalions to be deployed from march formation to battle formation.

Prussian gunner.

Με τις σημαίες να κυματίζουν και τα τύμπανα να ηχούν τα γαλλικά τάγματα βρέθηκαν απέναντι σε επτά πρωσικά τάγματα των μεραρχιών του αντιστράτηγου Φορκάντε και του πρίγκιπα Χάινριχ. Οι αντίπαλες δυνάμεις βρέθηκαν σε απόσταση μικρότερη των 30 μ.

Με απίστευτη ψυχραιμία το πρωσικό πεζικό άρχισε να βάλλει με τον γνωστό του καταιγιστικό ρυθμό. Το γαλλικό πεζικό, με θάρρος, προσπάθησε να αντέξει στον κατακλυσμό της φωτιάς και για μερικά λεπτά κατόρθωσε να ανταποδώσει τα πυρά, με σαφώς χαμηλότερο ρυθμό.

Σταδιακά όμως μεγάλα κενά άρχισαν να εμφανίζονται στις τάξεις των γαλλικών ταγμάτων, καθώς οι Πρώσοι γέμιζαν και έβαλλαν συνεχώς ανά διμοιρίες, διατηρώντας έναν συνεχόμενο ρυθμό πυρών. Σε λίγα λεπτά το γαλλικό πεζικό κλονίστηκε και άρχισε να αποσυντίθεται.

Ήταν η ώρα του Ζέιντλιτς. Το πρωσικό ιππικό, κινούμενο με απόλυτη τάξη, ως ζωντανό τείχος ανδρών και αλόγων, διέλυσε με ευκολία κάποιες συμμαχικές ίλες που είχαν απομείνει και επέπεσε στο πλευρό του συμμαχικού πεζικού. Την πρώτη κρούση δέχτηκε το αυτοκρατορικό πεζικό το οποίο σαρώθηκε, κυριολεκτικά.

Όσοι άνδρες διασώθηκαν πέταξαν τα όπλα και τράπηκαν, πανικόβλητοι σε φυγή. Η συντριβή του αυτοκρατορικού πεζικού προκάλεσε και την κατάρρευση του γαλλικού πεζικού που ακόμα πολεμούσε. Σε λίγο το σύνολο του συμμαχικού στρατού είχε τραπεί σε επαίσχυντη φυγή, αφήνοντας πίσω του χιλιάδες νεκρούς, τραυματίες και αιχμαλώτους.

Ο Ζέιντλιτς επιχείρησε να καταδιώξει τους φεύγοντες εχθρούς. Ωστόσο βρέθηκε ενώπιον των γενναίων Ελβετών, τα τάγματα των οποίων σχημάτισαν τετράγωνα και αντιμετώπισαν τους Πρώσους ιππείς με θάρρος. Χάρη στην αντίσταση των Ελβετών η πλήρης καταστροφή του συμμαχικού στρατού απεφεύχθη.

Ο Φρειδερίκος βλέποντας τον ηρωισμό των Ελβετών ρώτησε τους επιτελείς του:«Ποιο είναι αυτό το κόκκινο τείχος που τα πυροβόλα μου δεν μπορούν να γκρεμίσουν;». Όταν πληροφορήθηκε ότι ήταν Ελβετοί – οι οποίοι αντίθετα με το λευκοντυμένο γαλλικό πεζικό, φορούσαν κόκκινα χιτώνια- έβγαλε το καπέλο του σε ένδειξη χαιρετισμού της γενναιότητάς τους.

Ο ηρωισμός των Ελβετών πάντως έσωσε μόνο την τιμή της συμμαχικής στρατιάς. Στις 17.00 όλα είχαν τελειώσει και στο πεδίο, μαζί με την επερχόμενη νύκτα, επικράτησε μια παγερή ησυχία, μετά την ανθρωποσφαγή.

Η μάχη έληξε με τα πρωσικά όπλα να έχουν επιτύχει έναν θρίαμβο και μάλιστα έναν θρίαμβο φτηνό σε αίμα. Η μικρή στρατιά του Φρειδερίκου θρηνούσε μόλις 169 νεκρούς και 379 τραυματίες. Στην άλλη πλευρά οι νεκροί και οι τραυματίες ξεπέρασαν τους 3.000, ενώ 5.000 ακόμα άνδρες του συμμαχικού στρατού αιχμαλωτίσθηκαν.

Ωστόσο η κατάσταση ήταν ακόμα χειρότερη καθώς χιλιάδες άνδρες, από τους επιζώντες που είχαν τραπεί σε φυγή, ειδικά αυτοί του Αυτοκρατορικού Στρατού, λιποτάκτησαν. Χρειάστηκε σχεδόν ένας χρόνος για να μπορέσει ο στρατός αυτός να αναδιοργανωθεί.

Οι δυνάμεις του Σουμπίς υποχώρησαν ραγδαία, υπό διάλυση, με τον επικεφαλής τους να προηγείται της υποχώρησης, κατά πολλά χιλιόμετρα, των ανδρών του, αφήνοντας πίσω του πινακίδες για το που η στρατιά θα έπρεπε να ξανασυγκεντρωθεί.

Το βράδυ μετά τη μάχη ο Φρειδερίκος κατευθύνθηκε σε ένα γειτονικό παλιό πύργο για να διανυκτερεύσει. Όταν έφτασε εκεί όμως βρήκε το πύργο γεμάτο Γάλλους τραυματίες. Προκειμένου να μη διαταράξει τους αντιπάλους τραυματίες πήγε και κοιμήθηκε στο μικρό σπιτάκι ενός υπηρέτη του άρχοντα του πύργου.

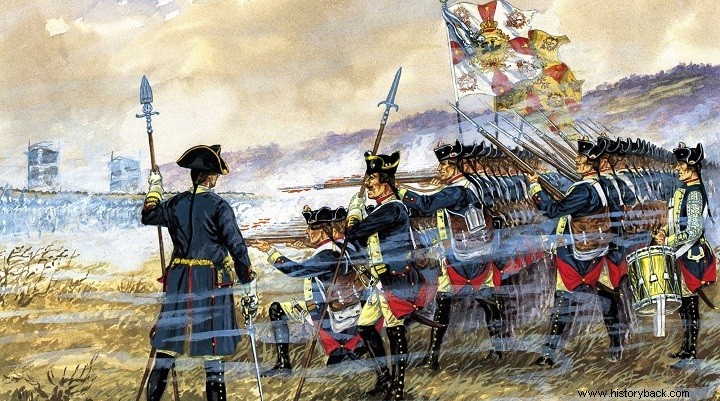

Οι Πρώσοι θωρακοφόροι εξαπολύουν την επέλασή τους.

Η μάχη του Ρόσμπαχ σε πίνακα εποχής.

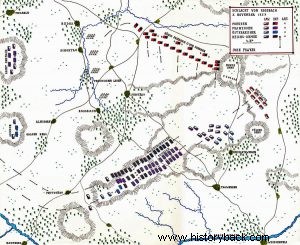

Χάρτης της μάχης προ της πρωσικής επίθεσης. Στο βάθος αριστερά διακρίνονται οι θέσεις των δυνάμεων του Σεντ Ζερμέν.