Erich Maria Remarque, in his excellent work "No Younger than the Western Front", presents a shocking scene where a phalanx of draft animals is hit by British artillery. Remarque shows a German soldier trying to kill the wounded animals so that they don't suffer, as he can't bear to hear "nature's own wail", as he eloquently puts it.

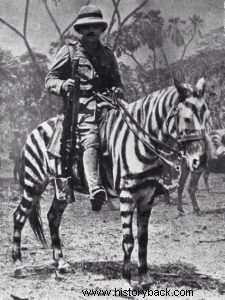

Animals have fought alongside man since prehistoric times, ever since the caveman tamed the first wolf. Since then, animals have always been in the heat of war along with humans, with the horse as their main representative.

Up until the Second World War, and in some corners of the planet until today, animals fought with the innocent heroism that characterizes them, sacrificing themselves, unyieldingly, for a purpose that they could not even understand. The proud horses, the humble donkeys, the sturdy mules, but also the dogs, the elephants, the camels fought loyally for their masters.

Like the dog of the unknown Greek hoplite at Marathon, biting the legs of the Persians who threatened his master, so the trained dogs of the Soviets rushed, carrying magnetic mines on their backs, under the German Panzers. Other dogs carried the machine guns of the Belgian Army in 1914 and others saved lives, discovering men buried in the trenches, from enemy fire. Others even carried the wounded, pulling them with their teeth to the dressing stations.

Others were trained to detect enemy mines, or carry messages. Hundreds of thousands of carrier pigeons also carried messages. Proud horses were used to pull chariots, to carry invincible knights on their backs, adding their own power, in the form of kinetic energy, to the warrior they carried.

In World War I, millions of animals, mainly equids, were used both by the warring cavalry units, as well as by the artillery and logistical support forces. Apart from the animals that were considered the mascots of their units – an Australian battalion had a koala with it and a Canadian a brown bear – the animals literally fought alongside the people. In this war even special anti-suffocation masks and devices were manufactured for horses, dogs and pigeons, to protect them from the chemicals. This fact also indicates their importance.

Stubby, the dog, fought alongside his master, part of an infantry battalion of the US Army, in 1918. Not only did he, thanks to his sense of smell, save the battalion from a surprise enemy chemical gas attack, but he also captured German soldiers, immobilizing them , until reinforcements arrive.

Sir Amy the pigeon carried 12 important messages to the warring divisions in the hell of Verdun. He delivered his last message, despite being shot, losing an eye and a leg, flying through a cloud of chemical gases. The Germans also used larger birds, such as falcons, to which they attached a small camera, so that they could photograph, from above, the enemy positions.

Even fireflies were collected, enclosed in glasses and used as a source of illumination, in the ambri dug deep into the earth. Behind the front, other animals were called upon to replace those missing from the front. Thus, instead of horses, even llamas were used, which were, until then, in zoos, for plowing the fields.

So do elephants. Such was the importance of the animals that a special service, the Blue Cross, was founded, which dealt with their care. Yet 90% of the animals used in human warfare were lost. In the British capital, London, a separate monument has been erected for these heroes of human absurdity.