The unification of Italy it was a process of union between the various kingdoms that made up the Italian Peninsula, after the expulsion of the Austrians. It took place in the second half of the 19th century and ended in 1871.

With this, the kingdoms began to form a single country, the Kingdom of Italy, under the reign of Victor Manuel II.

The late process resulted in the delay of Italian industrial development and the race to occupy territories in Africa.

Background of Italian Unification

The Italian Peninsula was formed by different kingdoms, duchies, republics and principalities very different from each other. To the north, part of the territory was occupied by the Austrians.

Each had its own currency, system of weights and measures, and dunes. Even the language was different in each of these regions.

Italy was predominantly agrarian and only the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia began to have industries, and thus, an influential bourgeoisie.

With the liberalism brought by the French Revolution, the Italian nationalist movements fought for the political unification of the country. However, with the defeats suffered in the Revolution of 1848, the dream of forming a single country seemed buried.

From 1850 onwards, however, the struggle reignites with the resurgence (Risorgimento ) of movements for national unity.

The coordinator of the movement for national unity was Camilo Benso, the Count of Cavour (1810-1861), who was at the head of the Risorgimento.

Cavour was the prime minister of the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the only region that adopted the constitutional monarchy as a government regime.

From this kingdom came the political leadership that would unify the other kingdoms of the Italian Peninsula, lead the expulsion of the Austrians and, later, fight the French.

Wars and Italian Unification

In 1858, the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia signs an agreement with France against the Austrian Empire. At this moment, Cavour's leadership stands out.

A year later, the First War of Independence against Austria begins. With the military support of France, the war against Austria ended with the battles of Magenta and Solferino.

France withdrew from the war after Prussia threatened to impose military intervention and the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was forced to sign the Treaty of Zurich in 1859.

In this, it was stipulated that Austria remained with Venice, but ceded Lombardy to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. The treaty also provided that the French would retain the territories of Nice and Savoy.

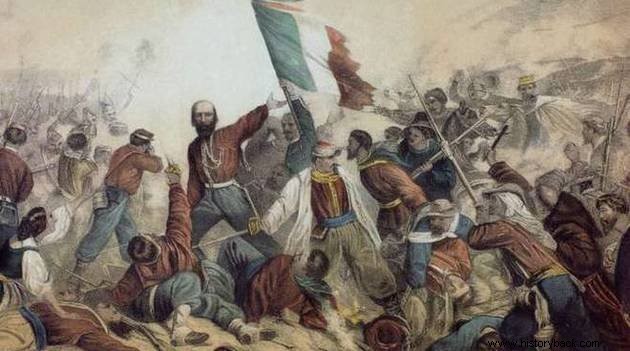

A parallel war, waged by Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882), husband of Anita Garibaldi, resulted in the conquest of the duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena, as well as Romagna. The territories were incorporated by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia after a plebiscite was held in 1860. Thus, the Kingdom of Upper Italy was born.

Also in 1860, Naples was conquered after Garibaldi's attack on the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

The Papal States were established at the same time and the movement resulted in the connection between southern and northern Italy. In 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was created.

However, it still remained to annex Venice, still occupied by the Austrians, and Rome, where Emperor Napoleon III (1808-1873) kept troops for the protection of Pope Pius IX. If before France was an ally of unification, now it was against the movement for fearing the emergence of a new power on its borders.

A parallel movement, traced by Prussia, tried to promote German Unification, which France was also against and, for that, had the support of Austria. The disputes culminated in 1866 in the signing of the Italo-Prussian pact and, in 1877, the Austro-Prussian War began.

Allied with Prussia, Italy received Venice, but was forced to cede Tyrol, Trentino and Istria to the Austrian Empire.

Only in 1870, when the Franco-Prussian War broke out, the Italian army was able to enter Rome due to the defeat of the French in that war.

At the end of the process, the unified Italy adopted the parliamentary monarchy regime.

The Vatican and Italy

When Rome was annexed in 1870, Pope Pius IX (1792-1878) declared himself a prisoner in Vatican City and refused recognition of unification.

In 1874, the pontiff prohibited Catholics from participating in the election that would vote the new parliament. This disagreement between the Italian government and the Vatican was called the "Roman Question".

The problem lasted until 1920 and was resolved with the signing of the Lateran Treaty during the government of Benito Mussolini.

Under the treaty, the government would indemnify the Catholic Church for the loss of Rome, grant it sovereignty over St. Peter's Square, and recognize the Vatican State as a new nation whose Head of State was the Pope.

For his part, the pontiff recognized Italy and its government as an Independent State.

Consequences of Italian Unification

The unification of Italy gave rise to a territorially united state under the constitutional monarchy. In this way, the country began its territorial expansion into Africa.

This attitude unbalanced the interests of the already constituted powers such as Germany and France and would lead to the First World War.

Curiosities

-

The wars of independence in the Italian Peninsula made many inhabitants immigrate to the United States, Argentina and Brazil.

-

Italian unification, commanded by the north of the country, has not reduced the economic differences between the north and south of the country until today.

We have more texts for you on the topic :

- Anita Garibaldi

- Flag of Italy

- Italian Peninsula