Antikythera , the island in front of Kythera, today it has only 44 inhabitants on an area of 20 km2.

In 1902 it was some sponge fishermen who found the wreck of an ancient sailing ship that was carrying a load of precious objects, statues, vases of fine workmanship and silver coins. They sought shelter on the island, surprised at sea by a violent storm. The ship came from Pergamum , the city on the coast of Asia Minor, and was headed for Rome who at that time admired the art, philosophy and technology of the Greeks.

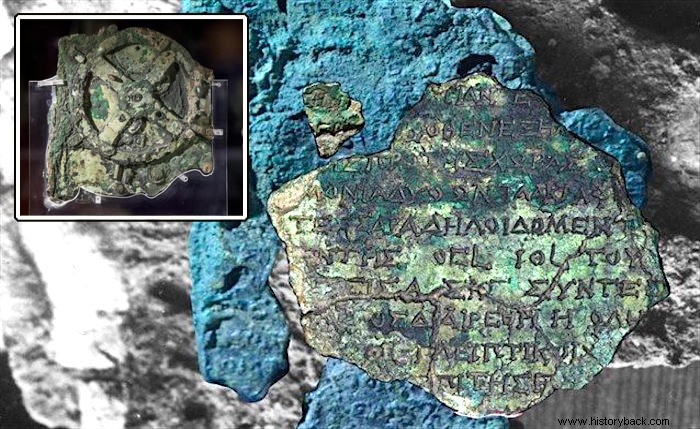

On board the ship, a mysterious bronze object was recovered, difficult to decipher due to the encrustations that covered it: the Machine of Antikythera .

No such instrument was built for the next 1,000 years.

Accurate analysis of the find traced, with certainty, the construction to 150 - 100 BC. C. Complicated gears were discovered under the encrustations and thanks to various fragments of the object it was possible to attempt a reconstruction. It consisted of about thirty bronze toothed wheels and had about 2,000 characters on the surface, with indications relating to the functioning of the mechanism . Today it is kept in the bronze collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Various, accurate investigations have made it possible to clarify the functions of the mechanism that was used in Ancient Greece to carry out complicated astronomical calculations .

It was used to calculate the movement of the Sun, the Moon in the Zodiac and probably also the movements of the five planets known at the time, as well as calculating the dates of future eclipses of the Sun and the Moon.

The technique used for its construction is similar to that which will be used only a thousand years later, in medieval Europe, for the construction of astronomical clocks.

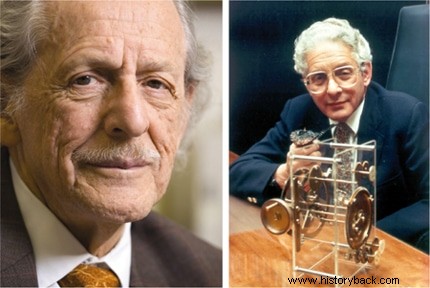

One of the most in-depth studies was carried out by the English historian of science Derek de Solla Price , who in 1951 began analyzing the machine. After twenty years of Price research he was able to discover, at least in part, the original functioning.

The whole mechanism was enclosed in a box about 30cm high, 15cm wide and 7.5cm deep and was built around a central axis .

When this axis turned, a system of shafts and gears came into operation that caused probable hands to move at different speeds, around a series of quadrants. The missing fragments prevented Price from understanding the complete functioning of the mechanism.

Of great importance, however, was his discovery of a 254 to 19 ratio between the wheels. This led him to connect the mechanism with the motion of the Moon relative to the Sun:in fact, the Moon makes 254 sidereal revolutions every 19 solar years. Price also proposed a first model of the machine which he then donated to the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, where it is currently on display.

In recent years, a multidisciplinary group of British, Greek and US researchers, the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project , was able to further deepen the analysis of the mechanism, thanks to new fragments found a few years ago, using technologies much more modern than those on which Price could rely, from computed tomography to high-resolution digital re-processing of the surface.

At the end of 2008, the news of the complete reconstruction of the ancient device arrived, curated by Michael Wright , an engineer from the London Science Museum . It is an exact copy of the original, with the same dimensions and the same materials. The new model is contained in a wooden box that is slightly smaller than a shoe box. In front there are two superimposed quadrants showing the zodiac and the days of the year.

Metal points indicate the position of the Sun, the Moon and the five planets.

The upper quadrant, explains Wright, represents the Metonic cycle, that is, the 19-year cycle . In this way it is possible to keep a calendar synchronized with both the course of the sun and the course of the moon. The lower quadrant was instead divided into 223 parts with reference to the so-called cycle of Saros , used to predict eclipses.

“It was not a research tool, something an astronomer would use to make calculations, nor would an astrologer use it to make predictions. It was something we would use to teach about the cosmos and our place in the cosmos, ”says Alexander Jones, professor of the history of ancient science at New York University. "It is like an astronomy textbook as they understood it at the time, which connected the movements of the sky and planets with the lives of the ancient Greeks and their environment. I would see it more as an instructive device for philosophers ».

The letters - some only 1.2 millimeters high - were engraved on the foils from the inside. Visible sections of the mechanism were enclosed in the wood and operated with a crank.

It wasn't exactly a manual, it was more of a long caption - like those in museums describing a work, says another team member, Mike Edmunds, emeritus professor of astrophysics at Cardiff University. "He doesn't tell you how to use it, he says 'what you see is so-and-so', instead of 'turning this knob and showing you something'", he says.