Homeric ideas about the Nile (12th-8th century BC)

Where do you find happiness after death?

Iliad and They Odyssey the epics give us many Homeric notions of life after death in the eyes of its heroes. Many of them are gloomy and hopeless in nature. In book 11, Achilles regrets that he chose a long, nameless life after death for a short life of fame. Other allusions to the afterlife similarly see the afterlife as a sad fall away from flesh and blood.

However, another character in The Odyssey , the sea god and / or old man Proteus, feels relief that his afterlife will be carefree in the fields of Elysium, along with Menelaus. Some scholars suggest that the contrast between Proteus' idea of his afterlife and that of Achilles shows a non-Greek origin to Elysium. Specifically Egypt.

After death on the Nile

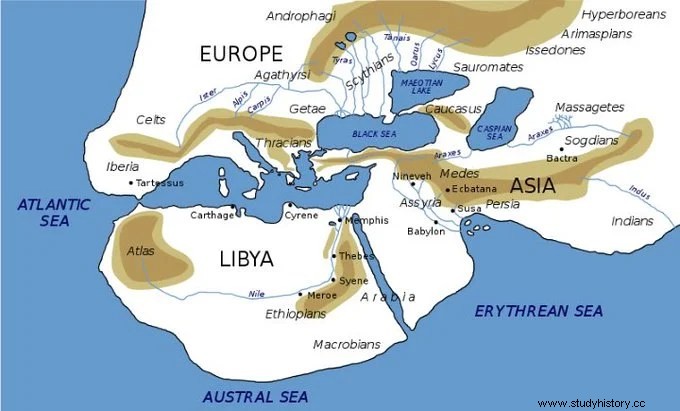

Many Egyptian religious concepts and practices left their mark on Bronze Age Greece from pan-Eastern Mediterranean exchanges (along with the Near East). Some may have survived into classical Greece in the form of mystery cults. A few of them include the "heavenly river that flows through the Field of Reeds," a flying ferry carrying dead pharaohs, and a rear-facing helmsman. Homer, or at least Homeric bards (12th-8th century BC), probably knew about the famous annual flood of the Nile. However, they disagree on the source of the flood, depending on their experience and ability to discover Egypt and the country to the south.

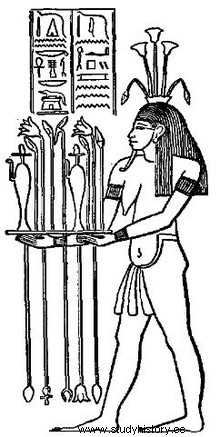

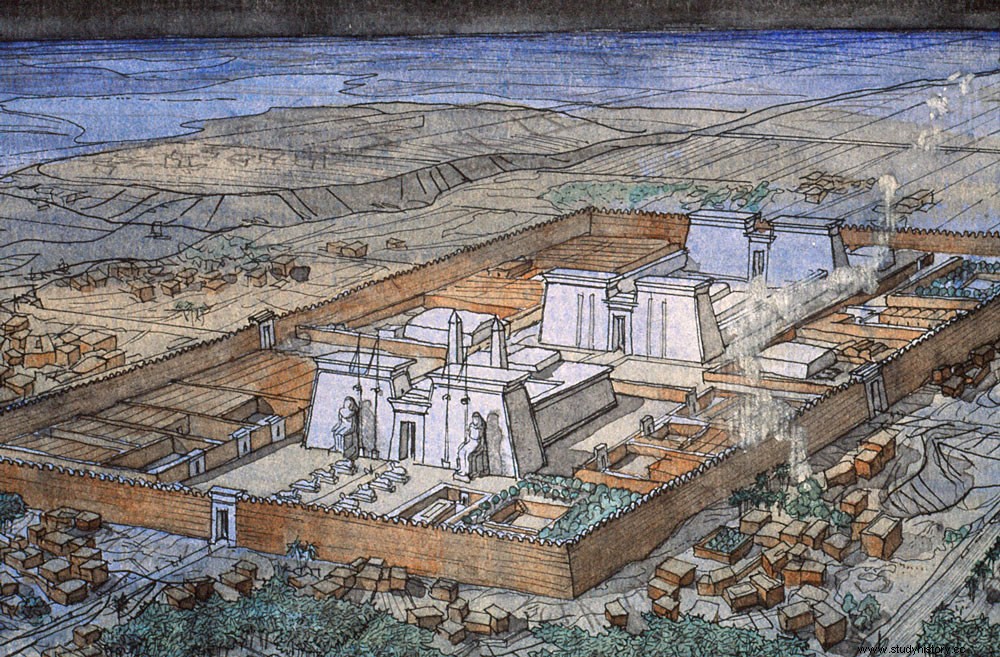

The natural form of Egyptian life after death was an idealized Nile in the sky, and its idyllic banks, the field of reeds or offerings. The rich and royal paid for their own fleet of scale boats to help carry them along this heavenly river. One of the best known examples of this is the discovery of Pharaoh Tutankhamun's fleet of 35 miniature boats. These boats looked like vessels made for functional and recreational activities in life.

We must all sail after we die

Without sufficient water-carrying vessels, one could drown. Drowning (in the river or sea) had enormous significance in Egyptian contexts. Drowning represented crossing a fine line between mortality and godliness best left to fate, and not exploited, intentionally or accidentally. Egyptians from New Kingdom who discovered that relatives had drowned in the Nile refrained from touching them. They let special Nile priests handle them. Drowning victims devoured by crocodiles were also left alone.

Where is the "sky-fed river"?

Some scholars claim that the expression "διιπετέος ποταμοῖο" ( diipetéos potamoīo ) in book 11 of The Odyssey translated as "fell from Zeus", and "swollen by (heavenly food) rain". However, there are at least 4 arguments that counteract this interpretation. The second word, "ποταμοῖο", means unequivocally river. It is the first word, "διιπετέος", which undergoes scrutiny. First, it is unconventional to use the prefix "διι-" in διιπετέος to indicate "from Zeus" (genitive) among ancient Greek dialectal declensions. Second, "-πετέος" probably does not come from the verb πίπτω (s.íptō - to fall).

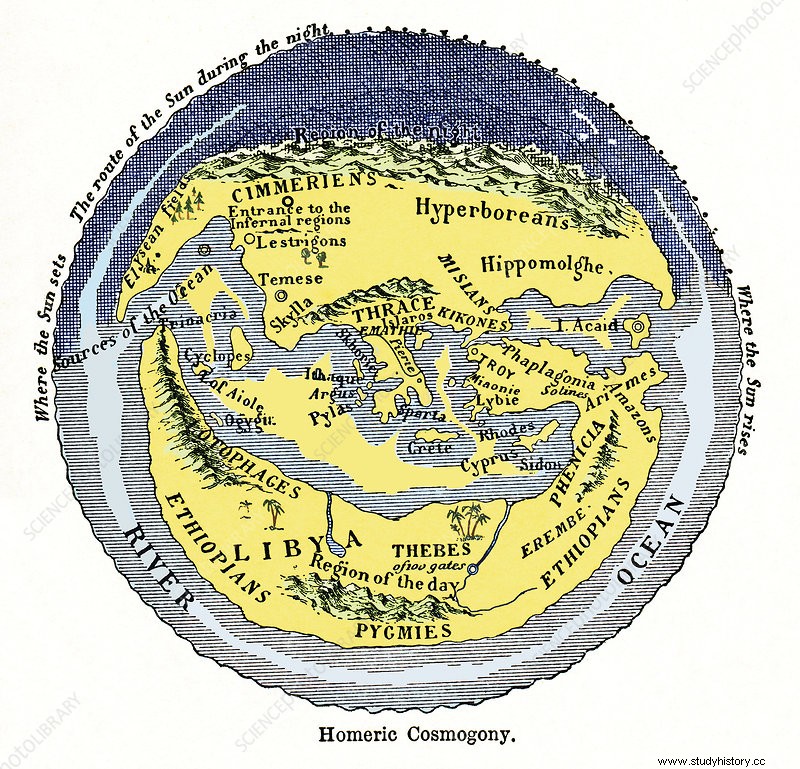

Third, the earliest post-Homeric occurrences of "διιπετέος" mean "translucent", far from "fallen from Zeus". However, celestial bodies and objects have connotations of purity, and therefore translucent. Fourth, the Iliad and Odyssey together have 3 named rivers described as "διιπετέος ποταμοῖο", one is the Nile. But we know that the Nile is hungry for rainfall. This is true, at least for the last 2,000 km of the river course in Egypt, which in itself was not yet fully discovered by the Greeks.

A river flying in the sky?

Other researchers have discovered other meanings for "διιπετέος", which include "fall through", "fly through" and "fly through" the sky We will focus on this interpretation of Homeric poetry, which describes the Nile as "a river flowing through the sky." Other Greek myths, and comparisons with Sanskrit texts, show that flying things (rivers, thunder, etc.) are to be expected. has tried to claim that a "flying river" is just one of many theoretical Indo-European motifs, such as the "twins".

However, if Sanskrit myths ever described a river as "flying", it would have been the great Indus, far out of reach of some Homeric Greek explorers. Another opportunity to identify the "sky-flying river" lies in Egypt. The Mycenaean Greece (the time epicized by Homeric bards) had significant contact with Egypt during the Akarnaat's Amarna period. The Nile and its floods were so famous that many cultures simply referred to it as the "river" or "indudation" (in reference to the legendary annual floods of the Nile).

Everything on earth is in heaven

A New Kingdom Hymn to the Sun, composed during the reign of Amenhotep IV Akhenaten, reveals an important Egyptian belief about the Nile. The river had a celestial counterpart, a perfect mirror in the sky. The water-rich river on earth sprang out of the underworld of Egypt. In contrast, the heavenly river kept all strangers in grace. During the day, this "river of heaven" was the ecliptic path of the sun god Ras. At night it was the Milky Way. In addition, Homeric academics were aware of this Egyptian belief in the Nile celestial mirror.

The ancient Greeks sometimes also saw rivers flowing through the sky. Sometimes they even personified them (eg Spercheius, another river mentioned by name). Others went on to attribute housing to them near Olympus. In light of this, the idea that "διιπετέος ποταμοῖο" ( diipetéos potamoīo ) is an allusion to the "heavenly Nile", and a stand-in for Egypt itself is still significant.

This heavenly Nile would naturally have been flooded by the sky. Whether the Greeks and / or Egyptians extrapolated this belief to assume that the Nile on Earth was also flooded by the sky is unclear. The Egyptians certainly attributed the Nile flood to many gods. In any case, the Homeric Greeks had clearly discovered the spectacular, annual summer floods of the Nile long before more prominent classical figures such as Herodotus.

Nile seen by Herodotus (5th century BC)

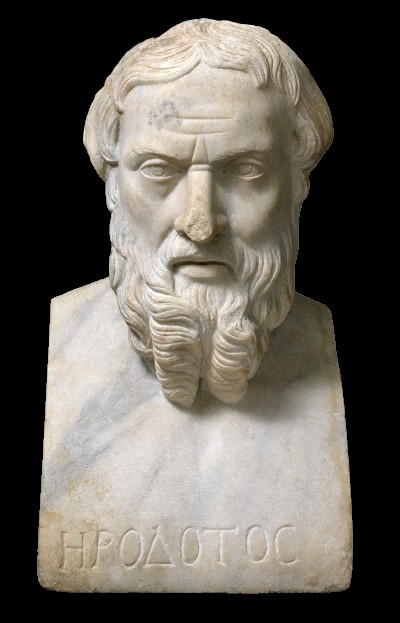

Herodotus' broader intellectual background

Herodotus came from Halicarnassus, and wrote in an Ionian (Eastern) dialect of Greek. Like other personas of Ionic intellectualism, he was interested in collecting eclectic ensembles of stories, events, phenomena for research. More importantly, the Ionic and pre-Socratic schools directly reduced the supernatural / divine causes of the wonders of the natural world ( thaumas ). In the midst of all these fantasies about the outside world, Herodotus was one of many figures who gave the locals first-hand evidence of areas previously shrouded in myth.

Herodotus 'invents peer-reviewed science' on Nile's origins

In the time after Homer, at least dozens of prominent Greek thinkers tried to tackle the origins of the Nile River, and the Nile itself. Some assumed that the "ethical winds" (annual winds that blow south in the Mediterranean summer) blocked the Nile from entering the sea, and therefore caused it to swell (Thales). Herodotus did not take this seriously; he and others observed that the Nile flooded with or without these winds. In addition, he noted that other, weaker rivers in Syria and Africa, which also flow in contrast to large winds, failed to demonstrate similar floods.

Herodotus considered another hypothesis even more absurd:a global ocean current floods the Nile (Hecataeus) at regular intervals. He also denied a third hypothesis:melting snow causes the Nile flood (Anaxagoras). He noted that this was superficially the most plausible hypothesis, if not for (what he thought was) facts about Egyptian geography and climate. The south is much warmer than the north, so there can be no snow. (Anaxagoras proved to be the "most accurate"; snow and rain start the Nile's surface water deep in the Central African highlands).

Where did Herodotus think the Nile came from?

Of course, Herodotus then offered his own 2 cents discovery about the origin of the Nile flood. It may be surprising that his theory does not address the flooding of the Nile at all. In short, the sun, which he strangely calls a god, attracts the same amount of water from all rivers. But because the Nile does not experience precipitation as much as other rivers, the Nile naturally dries up more in the autumn.

His theory is as dubious as others, not only with modern information, but from his own criticism of others. Namely, why does not his theory hold water for all other empirically observable examples? Diodorus Siculus makes this very complaint later in the 1st century BC

Herodotus and the Egyptians

To be sure, Herodotus consulted many Egyptian locals and taught priests about what they thought was the cause of the annual summer flood, which we may consider necessary and correct today. However, he refused to settle down with the many native explanations that simply pointed to one or many of the Egyptian gods as an end all be all. In fact, he was appalled by what he perceived as ignorance and indifference shown by "Egyptians, Africans and Greeks". He also regrets being "inflicted" by a scribe at the Temple of Athena in Sais, Egypt, who claimed to have discovered the source of the Nile.

Ptolemy's ideas about the Nile (1st-2nd century AD)

In the center of the world

Claudius Ptolemy (1st – 2nd century AD) is the next major figure in our review. His birthplace and home was Alexandria, Egypt. Egypt had now been under Hellenistic influence for almost 3 centuries. The Greek-built, cosmopolitan capital of Alexandria had reached a prominent position. It dominated culture, commerce and knowledge throughout the known world. It retained this position when Rome conquered it at the beginning of the empire, but not without concessions.

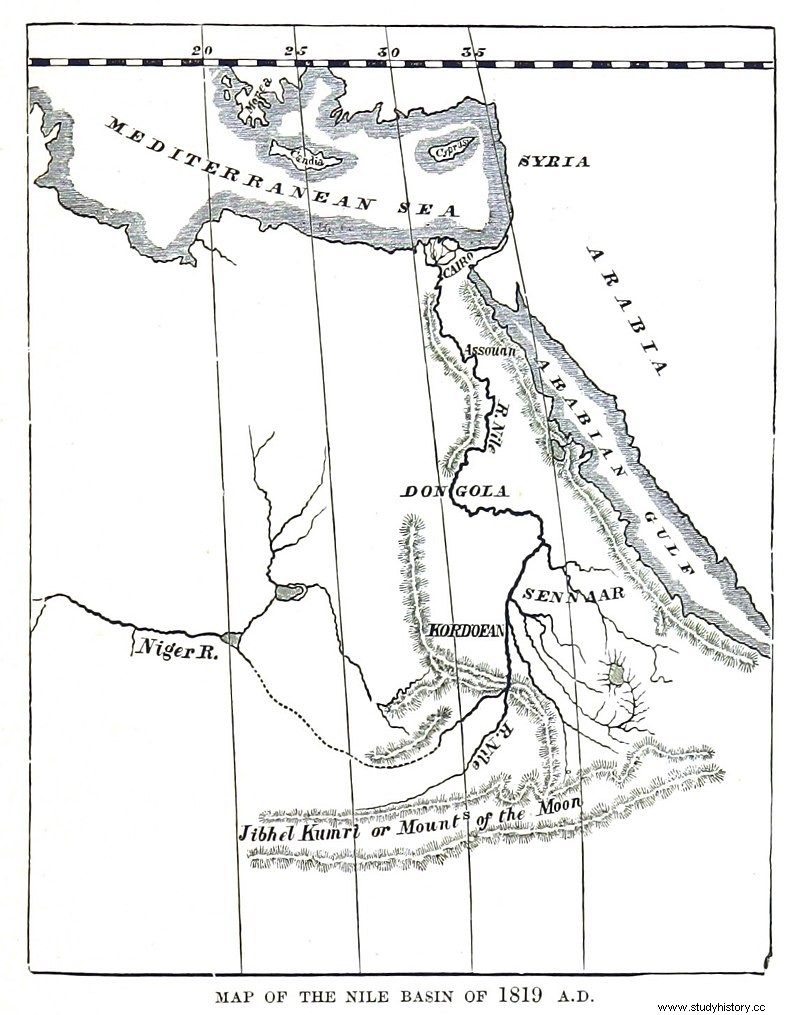

Ptolemy's synthesis of knowledge and theories about the Nile, and about geography in general, remained the basis of European geographical knowledge until the time of exploration (and into the 16th century). Modern scientists know him for, among many things, putting the idea of Mountains in Moon in focus as the modern hypothetical origin of the Nile. Despite the name, it is not clear whether Ptolemy really viewed the origins of the Nile as extraterrestrial.

Where on Earth was "Mountain of the Moon"?

The name Moon Mountain became a replacement for the true mountain range, no matter where it lay, which would not be fully discovered from the European perspective until the 19th century. The origin of the Nile has long been solved, but where Ptolemy himself may have located Moon Mountain is still a mystery.

Later scientists copied facsimiles of his maps until many of the transliterated foreign names on geographical features became cluttered. In the 13th to 14th Centuries, the Byzantine scholar Maximus Planoudis discovered Geography again, but without illustration ( Geography was never illustrated by Ptolemy, whose innovative cartography was used elsewhere). Many of the "Ptolemaic" maps we have today are probably from Planoudis, and their storage in the Vatican.

Error communication at least 3 times

Shortly before Ptolemy, a work entitled Periplus Maris Erythraei by an unknown author (possibly Arrianus, a Greek-speaking native Egyptian). It helps us to study the growing Greco-Roman geographical knowledge of East Africa, all the way to India. It also revealed important information about conditions in East Africa:there was significant tribal movement and technological transfer from the interior to the east coast, around the same time as Diogenes was blown off course along the east African coast. In addition, localities along the east coast of Africa used to have many more lakes and rivers.

the conclusion

This means that Ptolemy's identification of the Mountain of the Moon in both the East African coast and inland can be partially justified. The East African locals who had recently migrated from the hinterland to the coast, another area of large lakes, "failed to communicate" to Diogenes which lake system and mountains they referred to as the source of the Nile, their original hinterland or east coast. Ptolemy, as a third party recipient of such information (counting from Diogenes), may have felt the need to include both.

But we should also not assume that Ptolemy was necessarily worried about exact locations all the time. If anything, despite modern attempts to discover Moon Mountain at Mount Kilemenjaro or Ruwenzori they were metaphysical in Ptolemy's mind from the beginning.

Works Cited

Graham, Daniel W. "Philosophy on the Nile:Herodotus and Ionian Research." Apeiron:A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science 36, no. 4 (2003):291–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40913950.Griffith, R. Drew. "Homeric ΠΟΤΑΜΟΙΟ ΠΟΤΑΜΟΙΟ and the Heavenly Nile." American Journal of Philology 118, no. 3 (1997):353–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1561879.=Griffith, R. Drew. "Sailing to the Elysium:Menelaus' Afterlife ('Odyssey' 4,561-569) and Egyptian Religion." Phoenix 55, no. 3/4 (2001):213–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1089119.Sidiropoulos, G. and Kalpakis, D. "THE MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON:A Puzzle of the Ptolemaic Geography." BYZANTINA ΣΥΜΜΕΙΚΤΑ , No. 24 (2014):29-66. https://www.academia.edu/9587701/THE_MOUNTAINS_OF_THE_MOON_A_Puzzle_of_the_Ptolemaic_Geography