Like almost all countries, especially those that cover immense areas, China underwent a process of unification that culminated during the reign of the Qin dynasty, in the period of the so-called Warring States, in the year 221 BC. However, not everything was done, far from it, which is why less than a century later there was a last attempt by some kings to avoid the imperial claim to further centralize the territory. It was during the Han dynasty and is known as the Seven States Rebellion.

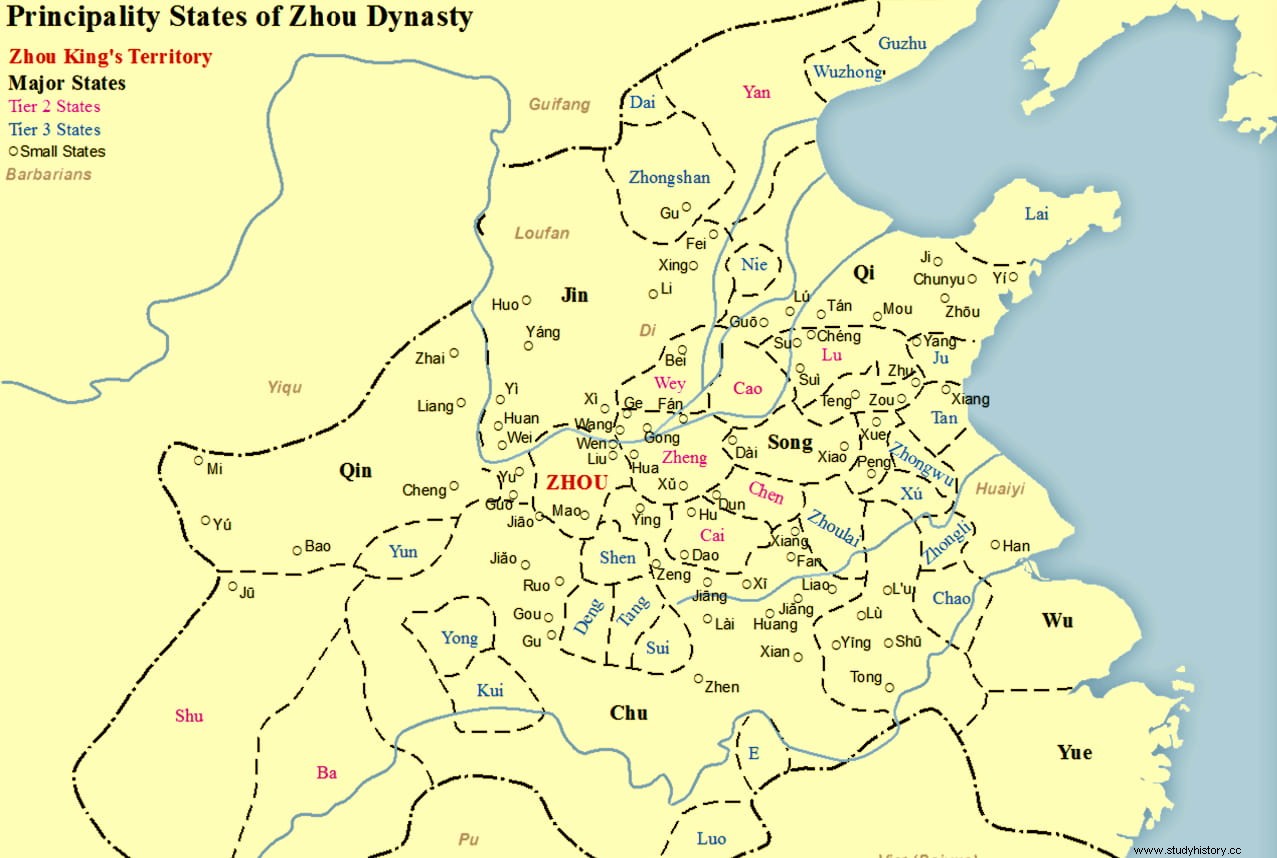

Before Emperor Qin Shi Huang consummated this unifying process, ancient China was divided into several very different states, some being authentic kingdoms while others, the majority, were nothing more than city-states; We are talking about a hundred and a half. They only had in common their weakness against the power of the Zhou dynasty, to which they surrendered vassalage. They were designated by adding the suffix guó (nation) at the end of their name and, in practice, these were fiefdoms, often granted by the wáng itself (king) in exchange for the corresponding provision of military services.

However, the larger kingdoms managed to stay out of it. For example, Wu and Yue (in the east), Chu (in the south) and Qin (in the west) were considered barbarians and were left out of that vassal bond, as were Ba and Shu (in the extreme west), to the that was not considered Chinese. This situation lasted until well into the 8th century BC, when what has been baptized as the Spring and Autumn Period began; about three hundred years during which four great powers emerged:Qin (west), Jin (central-west), Chu (south) and Qi (east), which little by little annexed other smaller ones and challenged the supreme authority of the Zhou.

The dynasty collapsed in 256 BC. By then, seven great states had been configured:Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Yan, Wei and Zhao, which were absorbing the minor ones but, at the same time, had to defend themselves against attacks from their rivals; in fact, not only from them but also from external incursions carried out by nomadic peoples such as the Quanrong or the Xiongnu. Qin Shi Huang, who is considered the first emperor of a unified China, was the one who took the lead after conquering those "non-Chinese" states of Ba and Shu. He then initiated a process of centralization and abolition of the feudal system, changing the status of the other estates to become mere administrative divisions run by officials appointed on merit rather than family ties.

Although the Qin dynasty only lasted fifteen years, its stage was fruitful:not only the territory was unified but also the currency, writing and weights and measures. It was also when construction of the Great Wall began, Xi'an's famous terracotta army was made, and an imperial legislative code was established. The Qian were succeeded by the Han, who changed their policy. On the one hand, they reinstated the classical philosophy that their predecessors had eliminated. On the other hand, especially during Gaozu's mandate, they transformed the parts of the country not directly controlled into principalities, at the head of which they placed their relatives, in the same way that they rewarded military acquaintances with fiefdoms. One and the other gradually increased their power until they constituted more than a third of the country, acquiring such strength that they minted their own currency, collected their taxes and had autonomous laws.

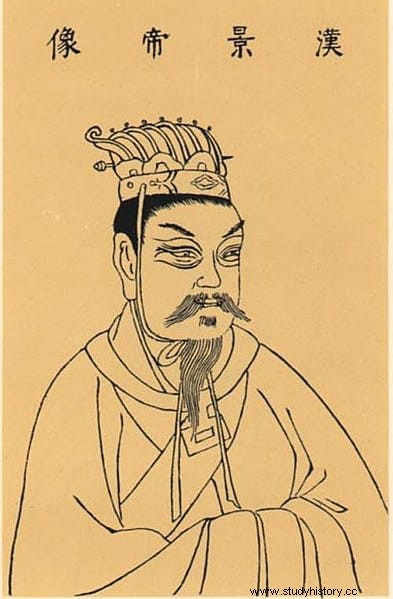

This led to a progressive detachment from the imperial government, with the principality of Wu as the most visible head. Thus came the year 156 BC, in which Emperor Jing came to the throne, determined to change things for various reasons. In the first place, to put an end to that growth that could turn against it at any moment. Second, because Wu was rich in natural resources, especially copper and salt. And thirdly, because it so happened that the ruler of Wu was his cousin Liu Pi, Emperor Gaozu's nephew, with whom he had open enmity. The latter was more serious than it might seem a priori, since years ago, when he was still crown prince, Jing had killed Liu Pi's son after he had insulted him in an argument over the departure of liubo (a board game) they were playing.

So Jing set out to abolish the fiefdoms again following the recommendation of his imperial secretary Chao Cuo, a renowned natural philosopher from Yuzhou (Henan province) who had already served the previous emperor, and at the same time end the threat of Liu. Pi. In Cuo's opinion, the ideal was to provoke them to rebel as soon as possible, so that they could be defeated without having time to establish alliances or obtain support. To do this, he suggested that their rulers be accused of crimes and, in effect, in 154 B.C. Liu Wu, Prince of Chu, was decreed to have had sexual intercourse during the period of mourning for Empress Dowager Bo (which was prohibited), while Liu Ang, Prince of Jiaoxi, was blamed for embezzlement and other princes - including Liu Pi- received various complaints.

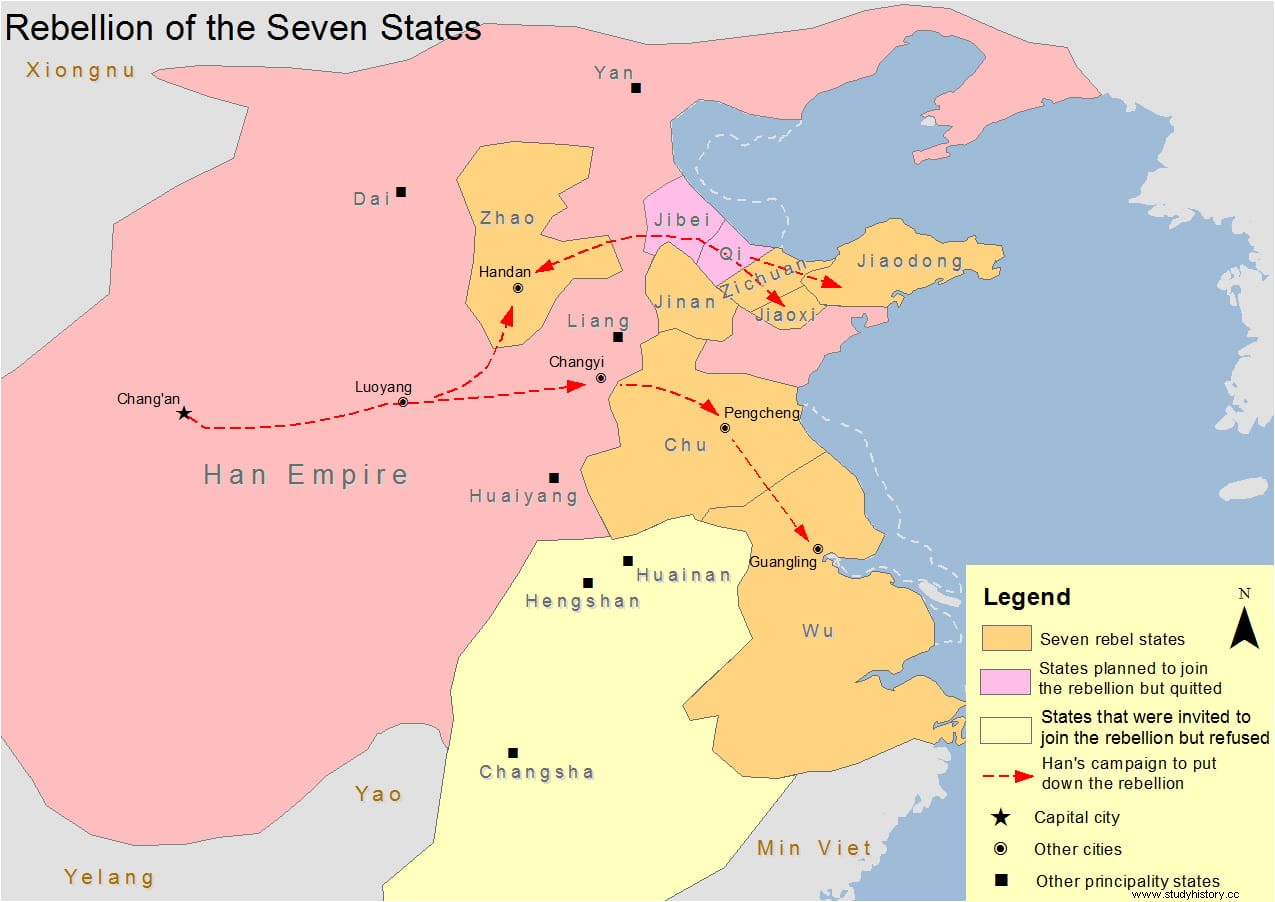

As the councilor foresaw, those territories rose up in arms in what is known as the Seven States Rebellion . The seven were Wu, Chu, Jiaoxi, Jiaodong, Zichuan, Jinan, and Zhao. Others like Jibei and Qi promised to join but never did, the former because their ruler was preventively arrested and the latter because in the end he preferred to support the emperor. As the principalities of Huainan, Lujiang, and Hengshan also stayed out, the rebels could only get help from the independent kingdoms of Donghai, Minyue, and Xiognu; the first two sent troops but the third limited himself to promising them, without fulfilling.

Interestingly, the first fatality of that conflict was precisely the one who lit the spark:Chao Cuo. His many political enemies in the court -something usual in that position-, of which the leader was the minister Yuan Ang, convinced the emperor that all this could have been avoided, that the rebels could have had their wings clipped unnecessarily to spark a fight. Consequently, that same year Cuo was executed with the aim of lowering tension and appeasing the rebels. However, Jing was faced with the harsh reality that he had been deceived in a fight between ministers, losing his best adviser while the rebellion continued.

There was no other choice but to confront him, for which he appointed General Zhou Yafu, who had been one of those who elevated the previous emperor, Wen, to the throne and had a well-deserved reputation for efficiency, both in the administrative and purely military fields. Yafu immediately went to the aid of the principality of Liang, ruled by Liu Wu, Jing's younger brother, whose capital, Suiyang, was besieged by the troops of Wu and Chu. But he did not come directly to break the siege but cleverly cut off the attackers' supply lines. Without food, they raised the siege to directly attack Yafu's camp but they failed and hunger spread among the soldiers, destroying the army.

Liu Pi had to flee and take refuge in Donghai, but he was killed. Liu Chu, Prince of Chu, committed suicide. Curiously, to these deaths it was necessary to add that of his winner, who died, according to tradition, by being too excited by his triumph. Now the war was not over. As the Principality of Qi had not kept its promise to join the revolt, its capital Linzi was under siege by four states. However, he managed to resist and that change of sides meant that his prince, Liu Jianglü, was forgiven by the emperor for his initial betrayal (although he, ashamed, chose to commit suicide).

That same end had the prince of Jiaoxi after the final defeat, while those of the other three states in revolt received the death penalty. Only Zhao remained but he depended on the arrival of Xiongnu forces which, as we saw, were never dispatched having changed the course of the war. Defeated, his prince Liu Sui also committed suicide. Thus ended the Rebellion of the Seven States, which lasted barely three months. China was definitely unified.