Like the rest of poleis of the Mediterranean area, throughout the fourth century BC. C. the Carthaginian army was made up of a citizen militia political type. Despite the reforms of Mago in the previous century, from which an increasing number of mercenaries had been introduced, the central body of the army was still made up of Carthaginian citizens, as can be seen in the battle of Crimiso (341 a C.), in which 10,000 participated (Plutarco Timoleón, 27' 4-5); number, however, remarkably small considering the size of the city. And it is that Carthage was populous and had great wealth, but this was enormously poorly distributed and the city lacked an extensive citizen body of small farmers with land, the base of the Greek and Roman armies, which was added to the enormous reluctance of extend the right of citizenship. With the passage of time, this situation did not change and before the alarming invasion of Africa by the Roman Atilio Régulo (256-5 BC), the Punic State could only mobilize a similar number in the Plains of Bagradas (Polybius I, 32' 9) .

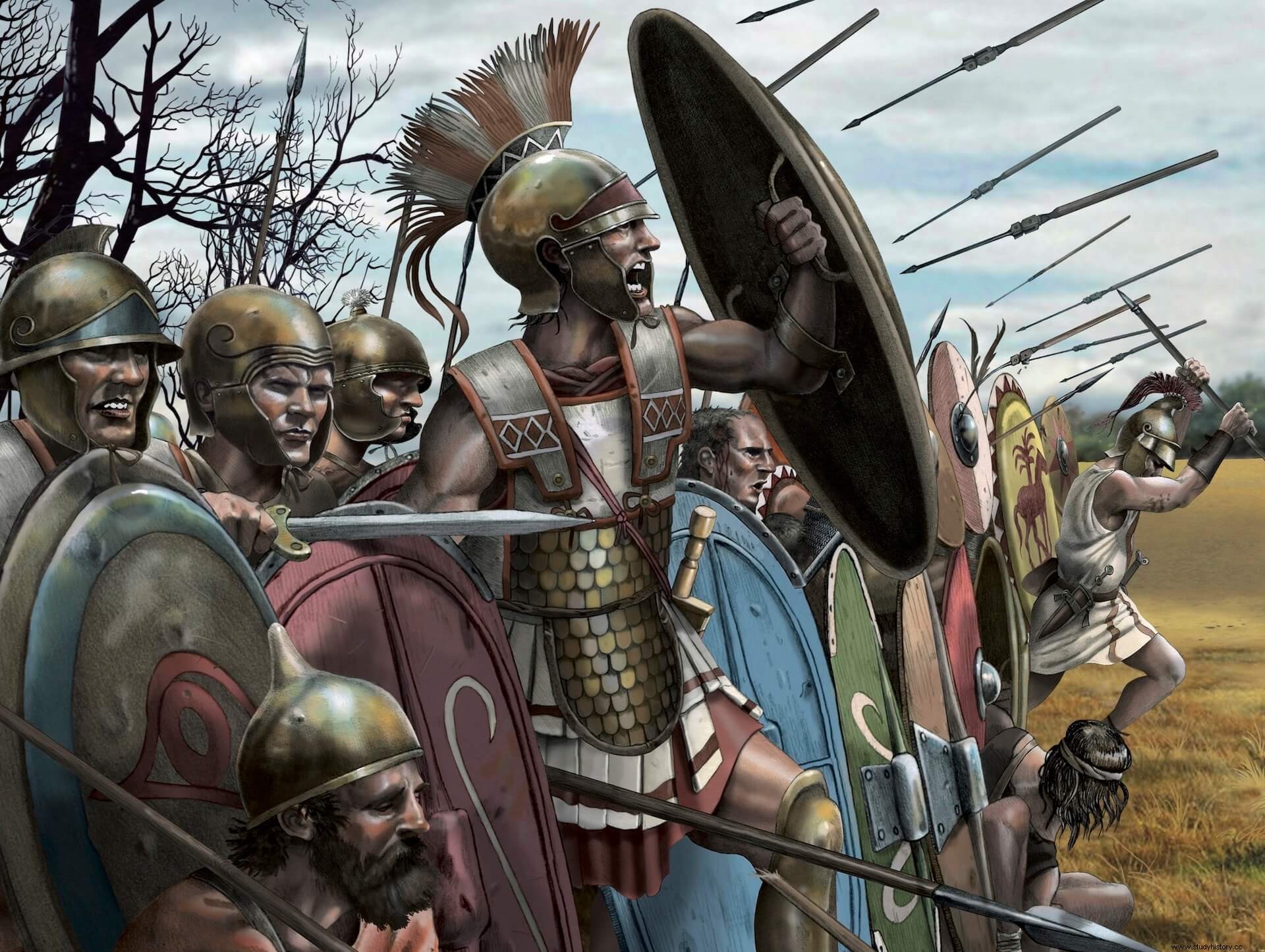

As the sources suggest, the Carthaginians fought in a phalanx, armed in hoplite fashion , with “iron armor”, probably scaled or lamellar; “bronze helmets”; and "great shields", as described by Plutarch (Timoleon, 28' 1) and as has been reflected in, for example, the relief of Chemtou (a city in northwestern Tunisia), which shows a clearly hoplite panoply, with round shield about a meter in diameter, convex and with a wide flat edge, associated with a linen Hellenistic-style cuirass, with shoulder pads and pteruges at the waist (see The War in Greece and Rome, by Peter Connolly). Panoply identical to the one shown in a tetradrachm minted by Agathocles in which the goddess Nike appears wearing a trophy armor probably of Punic origin. However, the spears represented on Punic stelae are similar in length to the height of their bearer and therefore shorter than that of the Greek hoplite. It is not surprising that the Punics copied the Greek fighting style, since the hoplite had been the owner of the battlefields throughout the Mediterranean for generations. On the other hand, after the disaster of Crimiso the Carthaginians "voted not to risk the lives of the citizens in the future, but to recruit foreign mercenaries, especially Greeks", which shows that they were aware of the superiority of the Hellenic infant (see Special IV :Mercenaries in the ancient world).

Among the citizen troops, the Sacred Battalion supposedly stood out , numbering 2,500, made up of men from "the ranks of citizens who are distinguished by their value and reputation, as well as by wealth" (Diodorus 16, 80' 4). However, there are several factors that make us doubt the existence of this body. And it is that it is only named twice by Diodorus Siculus:in Crimiso and in Tunis, when the Syracusan Agathocles he defeated them in 310 BC. In fact, in the much more detailed account of the Battle of Crimiso left us by Plutarch, he makes no distinction between the "ten thousand men-at-arms with white shields" whom the Corinthians surmised were all Carthaginians "by the splendor of his armor and the slowness and good order of his march”. On the other hand, it seems completely strange that an army of only 10,000 troops would have an elite corps of such a large size. And its name draws attention:identical to the invincible Theban battalion of 150 couples. The truth is that in none of the three Punic Wars or the Mercenary War (see The Inexpiable War in Special IV:Mercenaries in the ancient world) no source mentions the Battalion. Therefore, this was probably an invention of Diodorus to give more luster to the Greek victories over Carthage; although, obviously the higher classes could afford better (and flashier) weaponry.

Carthaginian infantry in the Punic Wars

The turning point in the evolution of the Carthaginian infant occurred as a result of the first war against Rome . If while in continental Greece it had been decided to strengthen the frontal clash of the phalanx at the cost of reducing mobility, the Macedonian phalanx took shape (see The reform of the infantry in the 4th century BC:from Iphicrates to the Macedonian Phalanx in Antigua y Medieval nº 21:Filipo II), in Carthage it was turned in the opposite direction. The constant defeats against the Roman infantryman, more agile and with more versatile weapons (scutum, pilum and sword); the type of warfare in Sicily, based on long sieges and sudden skirmishes in rugged relief, not conducive to the hoplite; and the Greek influence, where the thureophoroi was imposed as the mercenary archetype precipitated the change.

Everything indicates that they changed the traditional Argive shield, round, heavy and with a double handle, for the thureos/scutum, oval and with a horizontal central handle. In fact, during the expansion of the Barca family in Hispania in the last third of the 3rd century BC. C. This type of shield begins to become common in the Guadalquivir valley and the southeast of the peninsula, as revealed by literary, iconographic and archaeological sources. Another piece of evidence that should not be overlooked is that relating to the adoption of Roman weapons by the Libyans from Hannibal's army after the battles of Trebia (218 BC) and, above all, Trasimeno (217 BC). Exchanging the characteristic hoplite shield, which greatly determines the fighting style, for Roman weaponry in the midst of a military campaign abroad and without time for training would have been an unnecessary risk unbecoming of a victorious general. But what about offensive weaponry? Among the Romans, the use of the pilum was widespread, which was launched in salvos and then advanced to the melee sword in hand. Was this way of fighting the one already used by the Carthaginians (and Libyans) or were they still using the traditional spear? Unfortunately, there are not many references, but Polibio mentions the longche on several occasions. , a short, broad-bladed spear that served both as a lunge and to be thrown; and on the other hand several Carthaginian stelae (El Hofra, Cirta...) show oval shields, sometimes in conjunction with what looks like a short sword with a curved blade, a panoply confirmed by Appian and Strabo for the time of the Third Punic War.

However, we cannot think that the change occurred in a short time. When they were preparing to fight against the Romans in the Llanos del Bagradas (255 BC), the fact that the Spartan general Xantipo emphasizing in training the "order of march" and "regular maneuvers" (as we see in Polibius I, 32' 7) indicates that the phalanx was still present. On the other hand, the position occupied by the Greek mercenaries, to the right of the line, which was the most delicate position of a phalanx, supports this idea.

We need to make a point to explain a certain error that has been circulating for years. And it is that there has been much speculation about whether the Carthaginians could arm themselves in the style of a Hellenistic phalanx of pikemen . Xanthippus, as a Greek and great connoisseur of the art of war that he was, must have known this tactical formation. But the truth is that not even in Greece itself had the Hellenistic phalanx completely displaced the hoplite, and Xanthippus' native Sparta would not adopt it until the reforms of Cleomenes III (227-226 BC). Everything comes from various mistranslations from the Greek, which understood spear/pike when speaking of the longche .

It is tremendously difficult to analyze the Carthaginian infantryman in the immediately subsequent period, since the sources hardly leave us any clues. At Bagradas (240 BC) Hamilcar Barca carried out a series of maneuvers to first fall back and then confront the rebellious mercenaries that could hardly have been carried out by inexperienced Carthaginian citizens had they been wearing heavy hoplite gear. At Zama (202 BC), the second rank of Hannibal's army was made up of Carthaginian citizens, who performed with "frantic and extraordinary courage" (Polybius XV, 13'6) but failed to support the army. vanguard, undoubtedly due to lack of experience and although Polybius describes them as a phalanx, he also describes the Gallic, Ligurian, Balearic and Moorish mercenaries who, obviously, had nothing to do with hoplites.

Finally, after the second defeat against Rome followed aperiod of peace and reform . Hannibal was made a suffete in 196 BC. and he pursued a policy that favored the lower classes, increasing the power of the People's Assembly to the detriment of the oligarchy. His measures favored the awakening of the Punic economy and in just ten years the State coffers were already able to pay all the war debt (see Carthage between two Wars. A surprising recovery in Ancient and Medieval #31:Carthage Must Be Destroyed!). In the same way, it is also possible that the measures managed to increase the number of citizens capable of affording adequate weapons to train as line infantry. And if during the two previous centuries the maximum recruitable seems to have been around 10,000 infantrymen; the army commanded by Hasdrubal the Beotarch against Massinisa in 150 BC. C., had 25,000, to whom peasant recruits were added until adding a total of 58,000 men (Apiano Púnicas, 70).

In short, without neglecting its own idiosyncrasies, the evolution of the Carthaginian infant cannot be understood without the influences of nearby powers and the decreasing role it had, becoming a very particular case in the Mediterranean world.

Bibliography

Fonts

- Diodorus Siculus; World History

- Polybius of Megalopolis; History of Rome

- Livy Titus; History of Rome since its foundation

- Appian of Alexandria; Punic

- Plutarch of Chaeronea;Parallel Lives

- Herodotus; Stories

- Justin; Epitome of Pompey Trogus

- Silio Italico; Punic

- Zonaras; Epitome history

- Flower; Epitome of Roman History

- Eutropius; Summary of Roman History

- Valer Maximus; Memorable facts and sayings

- Cornelius Nepos; On the most outstanding generals of foreign peoples

Bibliography

- Peter Connolly; The war in Greece and Rome

- F. Lazenby; The first punic war

- Lazenby:Hannibal’s War, A military history of the Second Punic War.

- Adrian Goldsworthy; The fall of Carthage. The Punic Wars, 265-146 BC

- Duncan Head; Armies of macedonian and punic wars 359-146 BC

- Fernando Quesada Sanz; From warriors to soldiers. Hannibal's army as an atypical Carthaginian army

- Fernando Quesada Sanz; About the Carthaginian military institutions

- Fernando Quesada Sanz; Innovations of Hellenistic roots in the armament and tactics of the Iberian peoples since the 3rd century BC

- Fernando Quesada Sanz; Weapons of Greece and Rome

- Nic Fields; Carthaginian warrior 264-146 BC

- Nic Fields; Hannibal

- Jaime Gómez from Caso Zuriaga; Amílcar Barca, Tactician and Strategist. An assessment

- Jaime Gómez from Caso Zuriaga; Hamilcar Barca and the Carthaginian military failure in the last phase of the first Punic War

- Dexter Holes; Truceles War, Carthage’s fight for survival, 241-237 BC

- E. lendon; Soldiers and ghosts, myth and tradition in classical antiquity

- J. W. Tillyard:Agathocles