The year 1683 is the catalytic date regarding the Turkish one. extensibility. From the collapse of the Ottoman Army in Vienna, which occurred that year and later, the Ottoman Empire began to disintegrate. Of course, there were some Turkish successes later, but they were all of minor importance, unable to reverse the climate of decline and decline.

Within this context, the Venetian Republic decided to declare war on the Ottoman Empire, alongside the Habsburg Empire (Austria) and the German states under its control of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The Vatican State, the Knights of St. John of Malta and the Knights of St. Stephen of Tuscany were added to the allies.

In the area of the eastern Mediterranean, however, the burden of the struggle was borne by the Venetians. On the northern front respectively, it was the Austro-German forces that mainly fought. Poland and Russia, also members of the coalition, did not play a serious role in the military developments.

The Venetians officially declared war on April 25, 1684. It was the first time that the Venetians first declared war on the Turks. You immediately began to develop enormous activity in every field that concerned war preparation. Money was collected with which new military units were formed. After all, most of the men who served in the Venetian regiments were mercenaries, mainly Germans, but also Italians, Swiss and of course Greeks.

Whole regiments were still rented from the allied German states and some of the best generals of Europe were invited to command the army, for a hefty fee. Generals such as the Swedish Königsmark, the Italian-born Austrian Strasoldo or the German Degefeld, served honorably and exemplary under the flags with the lion of St. Markou and became the terror of the Turks.

Along with the army, the fleet was also strengthened, which was joined by papal (5), Greek (6), Maltese (7) and Tuscan (4) ships. Also agents of the Venetian Republic were sent to subjugated Greece in an attempt to co-opt the Greeks. The Greek ships were galleys from the Ionian Islands (one from Corfu, two from Kefalonia and three from Zakynthos), with Greek captains and Greek crews. At least 2,000 Iptanisians were assigned to the naval units of the Venetian fleet.

In the middle of the summer of 1684 the Venetian fleet led by an old acquaintance of the Greek seas, the veteran of the Cretan War Franciscus Morosini, sailed into the Ionian with the first objective of Lefkada. The siege of the island's fortress, the castle of Agia Mavra, began on July 21. With the assistance of the Iptanesian captains Maneta, Metaxas, Delladetsima, Anninos, but also the bishop of Kefallinia Timotheus – Timotheus himself put himself in charge of an armed body of 150 priests and monks – the fort was surrendered on August 6, 1684.

About a month later, Preveza had also been captured, while the Greeks of the western coast of Roumeli had taken up arms against the tyrant. The Greek charioteers Aggelis Sumilas, known as Vlachos, Panos Meitanis, from Valtos and the small Chormopoulos, were named. The bodies of these charioteers, reinforced by a body of Cephalonites and Ithacians and a regular Venetian body, under Strasoldo, overran Aetolia and part of Epirus.

The war rages

Outside Messolonghi, the Christian troops met the Turkish Sefer aga, defeated and dispersed them. Then they liberated Messolonghi and Aitoliko. By the end of 1684, a large part of the western Greek coast had been occupied by the Greek revolutionaries mainly, with the assistance of course of the Venetians.

On November 8, the citadel of Preveza, the last stronghold of the Turks in the area, was captured. The Turks responded to the military successes of the Venetians and the Greeks with massacres and looting of civilians. Among their victims was the bishop of Corinth, Agios Zacharias, who was skewered and roasted alive.

The new year (1685) was to be the most decisive for the outcome of the war. Initially, the Venetians did not even think about the possibility of generalizing the war or occupying extensive Greek Turkish territories. It was the initial successes that "opened" the appetite of F. Morozini in combination with some failures that occurred on the Dalmatian coast. After failing in Dalmatia, Morosini thought of conquering the Peloponnese.

He even asked for the cooperation of the Maniacs, who had already begun to gather weapons. The Turks, in order to prevent the uprising, preemptively invaded Mani and began their well-known "afro-freshness" - massacres, arson, dishonours. At the same time, Turkish forces were attacking Xiromero and the villages of Valtos. The forces of the charioteers were not sufficient to deal with the threat.

So Morosini ordered the Greek colonel Delladetsimas to rush to reinforce the rebels, at the head of a regular division. The Turks were indeed repulsed. But encouraging news also reached Morosini from Mani. The Maniates alone had succeeded in defeating Ismail Pasha, killing 1,800 Turks. Ismail, however, had another 8,000 soldiers ready for war at his disposal. So the Maniates urgently asked for Morosini's help.

In the summer of 1685 the Venetian and allied armadas entered the Messinian Gulf. It was June 24th. The next day the 6,400 men of the Venetian Army, under Degenfeld, began to besiege the fortress of Koroni. Hundreds of Greek volunteers had come with them, from the Ionian Islands, Epirus and Aitoloakarnania, who also joined other revolutionaries from the Peloponnese. The Turks tried to lift the siege of the strong and important fortress. However, they did not succeed, being defeated in a series of battles, and on August 11, Koroni surrendered to the besiegers.

The Venetians now had a secure port and an excellent base for their further advance into the Peloponnese. In the meantime, significant reinforcements arrived in the Peloponnese - 3,300 Saxon soldiers - and the Maniates also rebelled. In collaboration with the Saxon and Venetian divisions, they liberated all of Mani and the city of Kalamata. Thus successfully ended the second year of the war.

New conflicts and victories

At the beginning of June 1686 operations were resumed. About 10,000 infantrymen and 1,000 horsemen disembarked from the Christian ships at Paleo Navarino. The small army was placed under the Swede Königsmark and within a few days occupied Paleo and Neo Navarino and after defeating the army of the Serasker Peloponnese, besieged the fortress of Methoni. Methoni surrendered in turn (July 7). Kyparissia followed. The defeated Seraskeri, not daring to approach the Christian forces, limited himself to the slaughter of Greek civilians, burning villages and looting.

The demonic Swedish general made the most of his successes and immediately turned against the then Peloponnesian capital, Nafplion. The Christian troops re-boarded the ships and disembarked again at today's Tolo. From there they moved quickly and before the Turks realized what was happening, the Venetian flag was flying on the hill of Palamidi.

The surviving Turks then besieged Akronafplia. At the same time, however, help arrived. Ismail Pasha had arrived at Argos, at the head of 4,000 cavalry and 3,000 infantry. From there, with continuous raids, he harassed the besiegers and reinforced and supplied his besieged countrymen. The situation had become critical for Königsmark. His forces were between two Turkish divisions and were suffocating.

With constant attacks against Ishmael's forces, Königsmark contained the evil. But serious action was needed to break the deadlock. With this reasoning Königsmark attacked with strong forces against Ishmael's forces. It was the first line-up battle (of Argos) between the two rivals, which ended with the defeat of the Turks, despite their superiority in cavalry (August 7, 1686). The Turks after their defeat fled to Corinth. But they did not calm down. After being reinforced, Ismail decided to try the fate of the weapons again.

But again he was defeated by the Swedish general and his forces were dispersed. After the new defeat, the Turkish guard of Nafplio was forced to surrender the city. The defeated Ismail had retired to Aegio. But his soldiers, alarmed by the defeats and by the various rumours, began to abandon their positions en masse. There are even reported cases of entire divisions being halted and officers being killed by panicked soldiers!

For the coming year both sides were feverishly preparing. The goal of the Venetians was now the capture of the Achaean capital, Patras. However, the Turks were also willing to fight for Patras. The seraskeri of Peloponnese, after gathering strong forces - about 15,000 men - attacked the Christian forces - 14,000 men, at least 1/3 of them Greeks - who were preparing to begin a systematic siege of the city. The battle was fought on July 22, 1687, at the location of Ities. It was conducted with stubbornness, momentum and particular fanaticism from both sides. Ultimately, however, the discipline and superior tactics of the Christian forces prevailed. More than 2,000 Turkish soldiers were killed or wounded in the battle.

The rest fled, leaving the fortress of Patras and much booty to the victors. In their haste, the Turks abandoned even 14 of their ships in the port. The Christian army captured about 160 cannons, thousands of weapons, large quantities of food and ammunition and the seraskeri's own banner. The victory was complete. So complete in fact that the Turkish garrison of Rio abandoned the fortress without a fight!

The same thing happened on the opposite coast. The fortress of Antirio was also abandoned. And all over Sterea, the Greek chieftains had taken up arms and were fiercely fighting the conqueror, interrupting the communications of the Turks of the Peloponnese with those of Thessaly. Under the blessings and material assistance of the bishops Folotheus of Salona, Ierotheus of Thebes, Makarios of Larissa, Ambrosius of Chalkida, the charioteers of Livinus, Kurmas and Spanos, expelled the Turks from the whole of Phocis and Boeotia.

And Kurmas, on the other hand, gave battle in line with the serarsker of Thebes and routed him. The total losses of the Turks in the battle of Thebes exceeded 4,000 men. At the same time, the bishop Philotheos himself liberated his city of Salona. Only through the Isthmus could the Turkish forces of the Peloponnese communicate with their compatriots. Corinth was soon captured. Thus, the only Turkish possession in the Peloponnese was Monemvasia, which would finally be handed over to the Venetians only in 1690. At the same time, the Zakynthian chieftain Angelos Negris was occupying the fortress of Glarentza with his men.

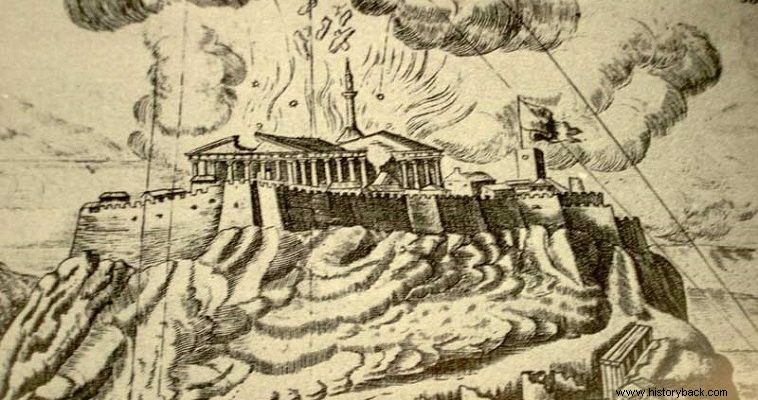

Athens - Acropolis

Having essentially captured the entire Peloponnese, F. Morosini wanted to secure his new conquests, occupying Athens and Chalkida. It would thus ensure control of the main roads leading to the Peloponnese. For this purpose, strong forces of the Venetian Army landed in Piraeus and from there marched towards Athens.

The Turkish garrison of the Acropolis had been alerted and calmly awaited the Christian army. On September 23, 1687, the regular siege of the Acropolis began. The Turks demolished the temple of Athena Nike, inside the fortress, to place one of their artillery in its place. The Venetian artillery lined up on the hills around the Holy Rock and started firing.

On September 12, a Venetian shell hit the Propylaia where the Turks stored gunpowder. The result of the explosion was to blow up part of the building. The next day, however, the great disaster happened, the only resurrection. A shell from a Venetian howitzer hit the roof of the Parthenon, piercing it and blowing up the barrels of gunpowder the Turks kept there. The temple was torn to pieces. Its roof was blown off, along with other architectural members and the remains of 300 Turkish soldiers.

Three days later the Turkish garrison surrendered. After the capture of Athens, even in this way, the Venetian army turned against Chalkida. But this enterprise failed completely. Among the victims was the brave Königsmark, who was affected by an epidemic disease. This failure had serious consequences for the fate of Athens. Without Chalkida, the Venetians could not even hold on to Athens. They were thus forced to abandon it and confine themselves to the Peloponnese.

The Traitor

The work of Morosini, which had been generally successful at the military level, was threatened to be destroyed by a Greek, Liverios Gerakaris or Liberakis. As we have seen, the infamous Maniati pirate had collaborated with the Turks in the past. So he was pulled out of the prisons, where his indiscreet pirate activity had led him, and he was assigned the mission to fight the Venetians in Sterea and convince the Greeks to side with the Turks!

In the spring of 1689, Gerakaris at the head of 2,000 Turks and various other scum - "Greeks" and Slavs - attacked Messolonghi and burned it down. He then plundered all the villages of Xiromeros and Valtos. It failed only against the fortified Aitolikos and Vonitsa. To deal with the situation, the Venetians set up two administrations, one based in Lidoriki in Phocis and one based in Karpenissi. Unruly Greek and Dalmatian bodies were subjected to these administrations.

Throughout the rest of the year 1689, small skirmishes continued between the rebels and Gerakaris' corps. The following year, Monemvasia finally fell. But Gerakaris was not disappointed. Now in charge of the Turkish side, the pirate Maniatis invaded the Peloponnese together with the Turkish seraskeri. He attacked and captured Corinth which he set on fire.

But he failed to capture Acrocorinth and Argos. Eventually the counterattack of the Venetian regular forces put him and his innocent allies to flight. Following this, Gerakaris attacked the liberated Nafpaktos. But he was repelled again and for the next 4 years he was limited to raids on unfortified villages of the Peloponnese, mainly.

Finally the Venetians managed to join him. Again, however, he appeared unfaithful and plundered Venetian-occupied areas. He was then arrested and imprisoned, where he died. It was only after his death that the Greek people breathed a sigh of relief and life in the countryside began to return to its normal rhythms. After his death, business virtually ceased. Small raids and conflicts at sea continued to occur, of course, but without having any particular impact on the strategic theater of operations.

The war finally ended in 1699 with the signing of the Treaty of Karlovic, based on the treaty the Venetians kept the Peloponnese, but not their conquests in western Greece and Nafpaktos.