The Greeks of the Mycenaean era had organized the most perfect military machine in the then known world. The Mycenaean Army consisted of infantry and cavalry weapons. The second included in its ranks chariots and later also horsemen, in the classical sense of the term. Infantry was distinguished into light and heavy. The heavy infantry should also be joined by the archer divisions, which did not fight in a strafing arrangement, but in a dense order, releasing "thunderbolts" of arrows.

All citizens received military training and were obliged to render military service. Each ruler had a core of permanent "professional" soldiers, mainly "tankers", who formed the hard core of the army. This core was flanked by strata units. The existence of a standing regular army in those early times is certainly surprising. But more surprising than this is the fact that the enlisted units were organized in regular groups, with certain leaders and a specific mission.

Each local military force was headed by the local king-ruler. Second in the hierarchy was "Lafayette", the commander-in-chief, the leader of the people, of the army. Next came the Epetae, the pro-army, the best warriors of the army. They in the Proto-Mycenaean period seem to have fought mainly on horseback, on chariots. Later they also fought on foot. Next came the heavily armed infantry, the satellites, who made up the early phalanx (any deep formation is called a phalanx). The poor now fought as petty men.

The Mycenaean Army formed a triple line of battle. Depending on the terrain, the strength and composition of the opposing army, and the corresponding friendly elements, the army was drawn up with tanks, light and heavy infantry, in separate lines. However, all three different "weapons" of the army cooperated harmoniously with each other and combined their actions.

Main instruments of judgment of the struggle were not tanks or heavy infantry. The mission that each section would undertake to carry out depended solely on the prevailing conditions on the battlefield alone. On the signs of Linear B' of Pylos, other military units (o-ka) are also mentioned, but we do not know what they represented. Each sub-unit had a chief, a non-commissioned officer we would say according to today's standards. Having the decarchy as an organizational basis, we could dangerously assume that each decarchy would constitute an element of the phalanx, or more simply that the Mycenaean phalanx of heavy infantry was deployed 10 yoke deep. We must not forget that in both classical and Alexandrian times, the element of the phalanx was its smallest tactical subunit.

The Mycenaeans, like the Cyclades or the Minoan satellites, initially at least, did not have the possibility of using the push tactics. Their weakness came from the type of shield they used, the foot. This shield was suspended, with the help of a leather strap, from the warrior's shoulder. It did not have a handle, similar to the buckle of the Argolic shield, of the "weapon", so that it could also be used offensively, as a weapon to break the enemy's shield wall.

The foot shield limited the satellites. But thanks to its suspension strap, the foot shield allowed the warrior to wield his long spear (3-3.5 m long) with both hands, giving power and precision to his strike. Against this early "Macedonian phalanx", no lighter formation had any hope of prevailing. The large shields made the satellites almost invulnerable to enemy projectiles, while no disproportionately armed division could approach the proto-Mycenaean phalanx's forest of spears without suffering crushing casualties. The heavy and powerful long spears had a brass point up to 60 centimeters long.

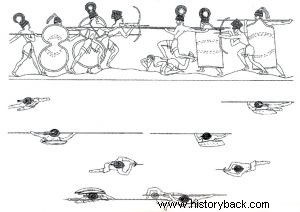

Its piercing ability was such as to enable it to pierce leather shields of the Amorite type, which were mainly in use in Eastern armies. The men's shields came together, forming a veritable moving wall. In a very dense formation (distance per man of the order of about 60 centimeters) the men of the first two ranks of the phalanx were able to thrust their spears straight forward. The men of the remaining yokes held their spears at an angle. Into the empty spaces between two men an archer entered, which was covered by the shields of the satellites (See photo).

Everything changed with the adoption, unknown exactly when, by the Mycenaean phalangites, of the eight-shaped shield. This weapon was also innovative for its time and gave even more power to the men who used it. The eight-shaped shield was almost the same size as the tower-shaped foot shield, but it was hollow. It was also made of layers of skins on a wickerwork frame. But it had a handle and shape, with a central strong wooden rib, that allowed it to push the opposing warrior and open a passage through the enemy's shield wall. It was the first shield in the world that not only allowed the fighter to use it in thrusting tactics, but rather forced it upon him.

But the problem was that it could still be used by the men of the first yoke of the phalanx, as an offensive weapon. The eight-shaped shield, for some reasons unknown to us, even came to be considered a cult symbol. Perhaps this cult of the Mycenaeans was due to its usefulness as a weapon and the victories it might have given them. Apart from the use of the eight-shaped shield, however, the battle tactics of the Mycenaean phalanx did not change radically, in relation to what was previously in force.

Another question you raise is why the Mycenaean satellites came to use such long spears when none of their rival nations used similar weapons. The adoption of long spears has much to do with the role of chariots on the battlefield of the time. The Hittites, Minoans, Mycenaeans, and to a lesser extent the Sumerians, in earlier times, were the only ones who used their chariots as instruments of shock and judgment in the struggle. The advance of the chariots was a terrifying sight, and there were seldom footmen cool enough and armed enough to meet it. Usually the infantry would lose their cool and "break" their yokes just before contact. The consequence of this was that the pedestrians were crushed, literally like spears, by the opposing tanks.

The infantry had to be equipped with a weapon that would enable the infantryman to keep his cool in the face of enemy tanks, a weapon on which the infantryman could pin his hopes of survival. After all, war since then was and remains primarily a psychological "game". Thanks to the long stretch, the Mycenaean infantry had both the practical and the psychological ability to resist the advance of the enemy's shock tanks. With its flanks covered the Mycenaean phalanx was almost impossible to break even by such an advance.

Besides, the horses of the enemy chariots were sure to categorically refuse - thanks to the instinct of self-preservation - to advance against the forest of spears presented by the phalanx. So in all probability the long sword was adopted as an antidote to the wound of enemy shock tanks. At the same time, however, it gave the Minoan and the Mycenaean infantry an equally important advantage in their fight against the enemy infantry, whose melee weapons were clearly shorter. Even the elite royal guard of the Hittite emperor was unable to face, on equal terms, a common division of Mycenaean phalangites. Things were even worse for the other opponents of the Mycenaeans in Europe and Asia.