They say that one day, at the beginning of the 17th century, a Portuguese captain faced an entire garrison of samurai in Nagasaki. The Portuguese were barely 50 men. The Japanese, about 3,000. And they endured like lions, aboard their ship, for more than three days of battle. This is the story of the titanic resistance of Andre Pessoa and the ship Mother of Deus .

It would not hurt to remember that, on the seas of the 17th century, the border between trade and piracy was quite blurred. We, Spanish-speaking readers, tend to think that the pirates were the English, Dutch and French who were after our Indian galleons. But, in the eyes of the people of Asia, the Portuguese and Spanish who arrived on their shores in those centuries were as much pirates as any Francis Drake. They didn't have a very good reputation, let's say. In fact, when they were far from their shores, European fortune sailors often behaved like true freebooters, and the thing used to lead not infrequently to conflicts with the locals. This Nagasaki incident is not the only similar crash that we are aware of. Iberian conquerors had already dealt with Japanese mercenaries in Siam, and the battles in Cagayan, in the Philippines, are also famous. But the story of Pessoa and his bravery is less well known, despite being possibly the most spectacular of all. This man's motto was “Rather break (die) than twist (bend) ”, and in Japan he was going to take this creed to its ultimate consequences. Centuries later, the Japanese would still remember the scenes seen in Nagasaki in January 1610.

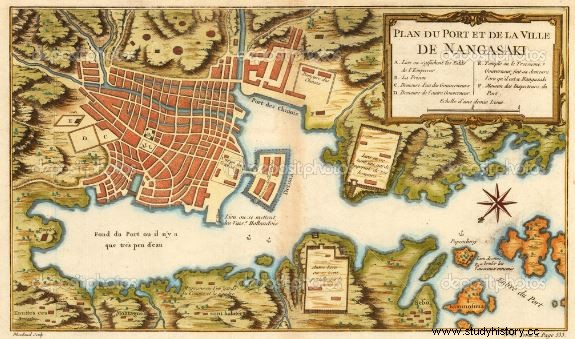

Nagasaki main port of Japan

There was a time when this city on the coast of Kyushu, the southernmost island of the Japanese archipelago, was the gateway that connected Japan with the entire world. From the end of the s. XVI, the port of Nagasaki became the main focus of international trade in the country of the rising sun. Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, Chinese ships passed through there... The city was a small melting pot of cultures, especially during the 16th and 17th centuries. A crossroads through which Catholic missionaries, fortune sailors, merchants from a thousand and one nations, corsairs, mercenaries, and people of all stripes passed on their trips through the Pacific. Virtually all foreigners arriving on Japanese shores entered the country through Nagasaki. This multicultural flavor comes from the very origins of the city. Nagasaki was officially designated as a port for international trade around 1570, and the Spanish and Portuguese navigators who flocked there eventually built a thriving metropolis on what had been a small fishing village until then. The lord of those lands, a converted Christian, ceded authority over the port of Nagasaki to the Jesuit missionaries in 1580, and from then on the holy fathers became the de facto owners and administrators of the city. Thus, Nagasaki quickly became the main Catholic focus in all of Japan. It was basically a Portuguese fiefdom, since most of the Jesuit fathers came from Portugal and took great pride in looking after the interests of their crown. But when Toyotomi Hideyoshi he took to persecuting Christians, things began to change. The Jesuits still had the upper hand, since they were the official intermediaries of all overseas trade, and also the important Christian community of the place supported them. But, from the 1590s, they were going to have to share power with a governor (the bugyo ) and an intendant (the daikan ) Japanese, imposed by the central government. And that system of shared power was to last until the moment of our history.

Portugal and the Passing Ship

With or without a Japanese governor, Nagasaki remained a vitally important port in the Pacific for the Portuguese empire. The Portuguese had reached the Japanese coast in 1543, being the first Europeans to show up there. From then until the end of the s. XVI had enjoyed an almost total monopoly in trade with Japan. The route of the black ships linked Nagasaki with their colonies in Goa, Macao and Malacca, and through those ports they moved a more than considerable volume of merchandise and wealth. The Portuguese brought the precious silk from China via Macao and sold it in Japan for silver; and that silver was, in turn, what the Chinese most coveted. As exclusive intermediaries in this triangular exchange, the Portuguese made gold. The business was so succulent that, entered the s. XVII, other powers began to interfere, and the Portuguese had to resign themselves to sharing the cake with the Spanish, Dutch and English. The Japanese themselves also began to send commercial expeditions on their own to neighboring countries. But Portugal remained the main trading power in those seas, and Nagasaki was one of the jewels in the crown.

Why didn't the Japanese go directly to China to buy all the silk they wanted? Not for lack of desire, of course. The thing was complicated. The China of the Ming dynasty, the same ones that have become famous for their vases, was not in the business of having Japanese ships prowling its ports. They had been enduring for literally centuries Japanese piracy, which from time immemorial swept across their shores like a plague of locusts. The Ming got their noses swollen and chose to close their ports to trade with Japan and its neighbors. Of course, that didn't solve the problem, and pirates from all over Southeast Asia continued to rampage when they raided the China Sea. But, for nearly 200 years, the only way to get hold of any Chinese product was by force. They needed an intermediary, and that role was gladly assumed by the Portuguese. For the Japanese, the black ships had come as if they had fallen from the sky. Thanks to them, they could finally enjoy Chinese silks and manufactures again. And, if in passing the Europeans sold them gunpowder and the occasional arquebus, then honey on flakes. All this trade was articulated through a system very similar to the one the Spaniards used with their famous Manila galleon . ThePassing Ship , a large carrack, set sail from the port of Macao (on the Chinese coast) and carried silk to Nagasaki. There they shipped all the silver that the Japanese gave them as payment and returned to Macao, where the Chinese took the ingots from their hands. And the Portuguese, obviously, made a fortune from the whole process. Normally the route was made once a year, and the lucky captain of the Ship of Passage earned so much that he could perfectly retire after a single trip.

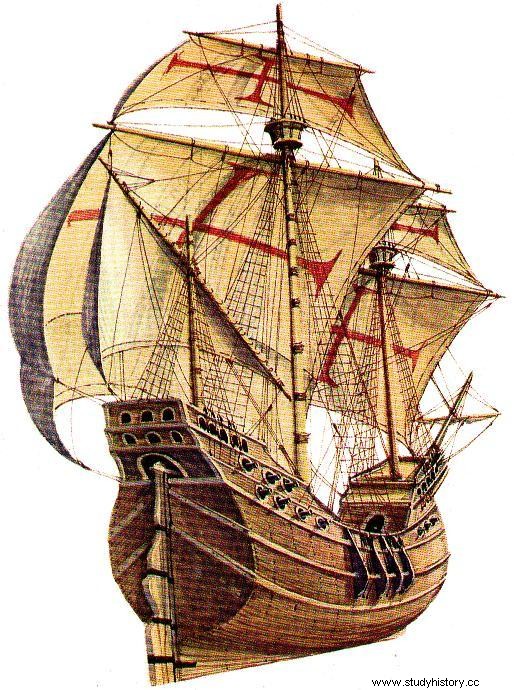

Kurofune (black ships)

The Japanese called it “kurofune ” (black ships) to the Spanish and Portuguese ships, due to the unusual color of their keels

Of course, the Nave de Paso, with its unmistakable keel all covered in black, was a more than appetizing booty for all pirates region of. The route to Macau was a dangerous journey, although the risk was as high as the benefit. It was the jewel of the South Seas. In 1609, the honor fell to a purebred Portuguese fidalgo named Andre Pessoa . A brave and bold guy who is going to be the great protagonist of this story. Despite being born in the middle of the Iberian Peninsula, he was going to prove to be more of a samurai than the samurai themselves.

Trouble in Macau

It all begins in the Portuguese colony of Macao in 1608. Andre Pessoa, brand new captain of the Ship of Passage the following year, was finalizing the preparations for the great voyage. Being the captain, Pessoa acted as de facto governor of the colony and had command in place over the local garrison. At that time, a Japanese merchant arrived from Cambodia, and intended to spend the winter there. The ship sailed under the flag of Arima Harunobu , Christian daimyo and lord of the province of Hizen, the same province to which the city of Nagasaki belonged. Since their arrival in Macao, the Japanese crew behaved in an arrogant and quarrelsome manner. They roamed the local taverns in gangs of 30 or 40 men, armed and setting up a brawl wherever they went. More than sailors, they looked like a gang of thugs. And that's just what they were, as the crew was made up almost entirely of adventurers, soldiers of fortune, and wako , mercenary pirates of those who had been sowing terror on the Chinese coast for centuries. Dangerous people indeed. In the words of a European sailor of the time:

They are meek people when they are in their land, but authentic devils when they leave it.

Concerned local merchants complained to the colony authorities, and the Japanese were given a warning for misbehavior. But, far from calming things down, that only made things worse. The Japanese wako were getting more and more cocky, and they acted as if they were the masters of the place. There were those who even feared that they would try to take the city by storm. The tensions were growing and, sooner rather than later, the rope ended up breaking. On November 30, 1608, the Japanese were involved in a street brawl, and things escalated until a real pitched battle was mounted in the middle of Macao, with church bells ringing. So Andre Pessoa, captain of the Ship of Passage and highest authority in the city, had no choice but to take matters into his own hands. He gathered all the men-at-arms that were available in Macao and, well equipped and armed, they showed up at the scene with the intention of putting an end to that commotion in a fast way. The Japanese rebels, seeing what was coming upon them, entrenched themselves in two mansions, which Pessoa's platoon surrounded. Surrounded on all four sides by arquebusiers, the wako had few options left, but fidalgo Pessoa, a magnanimous man, decided to offer them quarter if they surrendered peacefully. In the first mansion, the majority accepted the offer, although a group of irreducible steadfastly refused to lay down their arms. Predictably, they were cut down to the last man by the lead from the Portuguese cannons. In the second mansion the scene was somewhat different. Pessoa managed to get the rebels to surrender under the promise of respecting their lives and letting them go free. Let us remember that, violent or not, they were men in the service of the daimyo of Nagasaki, Arima Harunobu. But here our captain did not behave so honorably because, as soon as he had them out of the house, he forgot his word as a hidalgo and had the leaders of the insurrection hanged. He only allowed the rest to embark back to Japan after making them sign an affidavit in which they assumed full responsibility for the altercation, absolving the Portuguese of any blame. The Japanese, defeated and humiliated, weighed anchor towards Nagasaki, and the inhabitants of Macao breathed content and happy. But, as we will see, things were not going to stop there.

The Passing Ship sets sail for Japan

Pessoa continued with the preparations for the imminent departure. Due to pressure from Dutch pirates, in 1607 and 1608 the Ship of Passage had been unable to leave Macao. Therefore, Pessoa's in 1609 was going to be the first Ship of Passage in more than two years, and the expectation was palpable throughout the Pacific. That year the ratchet was loaded to the brim with riches. She literally carried two whole years' worth of cargo. We do not know for sure the name of the ship, as some sources call it Nossa Senhora da Graça and other Mother of Deus . We will stay with the latter because it is shorter. You know, economics of language and all that.

17th century ratchet

Filled to bursting with silks and wares of all kinds, the Madre de Deus she sailed from Macau in May 1609, several weeks ahead of schedule. Captain Pessoa knew what he was doing:his haste to set sail served him to mislead the Dutch corsairs who were lying in wait. At the end of June she arrived without major mishap at the port of Nagasaki, with her precious cargo in full. But what awaited them there was not exactly the warm welcome they had hoped for. At first, the port authorities put all the obstacles imaginable to unload their merchandise. They even demanded to go on board to inspect the ship, something unusual. Pessoa, indignant, flatly refused to bow to his demands, and that only bogged down the situation. When they were finally allowed to disembark, the problems continued. Nobody was willing to pay the usual price for Chinese silk, and there was no choice but to drop prices. In the end, the governor of Nagasaki got the best lots for much less than what had been paid in any of the previous years and the Portuguese, who had gone there expecting to do the deal of the century, were left with a span of noses .

The reasons for this unfriendly treatment are not clear. Possibly news of the incident in Macau the previous year had arrived and, Nagasaki being part of Arima Harunobu's fiefdom, they had it in store for Captain Pessoa. Be that as it may, the governor of the city sent a formal complaint to the shogun about Pessoa, denouncing his insolent manner and accusing him of being a swindler. He and his crew, they said, behaved with total impunity, protected by that virtual extraterritoriality, that special status that Nagasaki had, a city more Portuguese than Japanese. The expulsion of the Portuguese from Japanese soil was even hinted at. Things were getting very ugly. Using diplomacy and a few bribes, Pessoa tried to calm the governor of Nagasaki with the mediation of the local Jesuits. But the diplomatic tug-of-war, with couriers going back and forth between Edo and Nagasaki, dragged on for months. And the animosity between Pessoa and his enemies only grew.

Arima Harunobu

Arima Harunobu was the lord of the province to which Nagasaki belongs; officially those were his lands and his duty was to defend them. The captain finally got fed up and decided to send a formal complaint to the shogunate himself. That is, to Tokugawa Ieyasu , who despite being officially retired was the one who was still in charge. In his letter he put the governor of Nagasaki and his cronies back and a half, and demanded to assert his old business privileges. The Jesuits, who understood much better than Pessoa how things worked in Japan, nearly gave them a shock when they found out. Because the governor of Nagasaki was also the brother of Ieyasu's favorite concubine. Yes, at 67 years old, the old fox was still cavorting with the girls in his harem as if he were a boy. The fact is that Ieyasu drank the winds for that woman, to the point that, in the words of the holy fathers, "if she says that white is black, Ieyasu will believe it at face value ”. In the end the Jesuits managed to talk sense into Pessoa, even threatening to excommunicate him, and the captain refused to send that letter to Ieyasu. But the damage was already done. The governor and mayor of Nagasaki had found out everything thanks to their contacts, and both swore to make them pay the cheeky Portuguese captain. The local daimyo, Arima Harunobu, wasn't too happy with all the fuss either.

And just when it seemed like things couldn't get any worse, they got a little worse. Pessoa was still trying to undersell his cargo as best he could when, in September 1609, the survivors of the famous Macao incident showed up in Nagasaki to account for what had happened to his lord. His report, as you might imagine, did not leave Captain Pessoa in a very good place. The sworn confession he had forced them to sign was a pack of lies, and the dignity of Arima's men had been trampled on. This reached the ears of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the matter became a matter of national pride. Japan could not allow her subjects to be treated like this, in Macao or anywhere. The daimyo of Nagasaki, Arima Harunobu, demanded blood to wash away the insult. And, by the way, he advocated confiscating the Madre de Deus whole, with load and everything. Even without counting the riches he carried in his cellars, a Portuguese galleon, the latest technology at the time, was always a welcome prize. But Tokugawa Ieyasu, prudent as always, hesitated. As far as possible he wanted to preserve the trade route with Macao, and for that he had to be on good terms with the Portuguese. In the end, the coup de grâce for the fate of the Mother of Deus He came from a totally unexpected place:from the Spanish side.

A Spanish galleon traveling between Manila and New Spain (Mexico) had been shipwrecked off the Japanese coast. On board was the recently replaced Governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco , whom Ieyasu received as a personal guest in his own castle. Don Rodrigo, who must have seen business opportunities, let Ieyasu know that the Spanish crown could perfectly supply the needs of Japan in the silk trade with China. If the Portuguese sent him a ship a year, he promised to send them three, or as many as were needed. It is interesting to note that, in 1609, Spain and Portugal were united under the same crown. Technically, since 1581 they were the same country. But, as we can see, when it came to the truth they weren't very well matched and, if they had the chance to kick each other's asses, they didn't hesitate to do it.

Things get tough for Pessoa

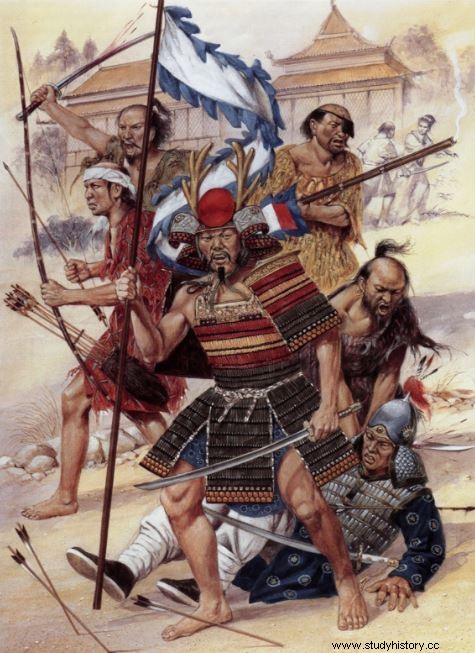

As it was, as Ieyasu saw it, Japan did not need the Portuguese at all. There was no longer any reason to continue putting up with the impertinence of Andre Pessoa and his men. To the delight of the governor of Nagasaki and his compadres, Tokugawa Ieyasu himself gave the order to confiscate the ship with all its cargo and arrest the captain. Pessoa found out about the intrigues against his person thanks to the Christian community of Nagasaki. Neither short nor lazy, he prepared to go to sea as soon as possible. He began loading industrial quantities of grenades and gunpowder into the holds, but preparations for overseas voyages took time and he was not ready to set sail until after New Year's Day 1610. During all that time, Pessoa did not set foot. off the ship not even to go to mass. There he was safe, in his floating castle, protected by his cannons. He knew that if he went ashore, he couldn't give a dukedom for his skin. Meanwhile, the damiyo Arima Harunobu sent messengers to tempt him, offering assurances that he had nothing to fear. He begged him to go down to the port to talk and be able to settle that ugly matter once and for all, but the Portuguese continued in his thirteen. He didn't trust even his shadow. His crew, on the other hand, were less aware of the threat that loomed over them. They thought that everything was a simple fight between their captain and the Japanese bigwigs, nothing to worry about. Instead of fussing about rigging the ship, they preferred to indulge in local delights in Nagasaki's taverns and brothels. Little did they know that while sending embassies to placate Pessoa, Arima Harunobu had recruited a squad of 1,200 men to launch against the Madre de Deus . On January 3, 1610, when the bulk of the crew wanted to embark, it was already late. Armed guards barred their way, while Arima's soldiers occupied the port and began hostilities against the Portuguese ship. Pessoa only had a handful of men on board. About 50 sailors and a few black and Indian slaves. That was all the army he could count on to deal with the entire Nagasaki garrison. The fate of the Portuguese seemed cast. Arima Harunobu could be sure of victory. What was a sad rattle going to do against an entire battalion? But it turns out that Andre Pessoa was in charge of that ratchet. And, true to his custom, the brave fidalgo was going to give the hosts of Nagasaki a battle they would never forget

At the boarding of the Madre de Deus

With the port completely surrounded and the Madre de Deus anchoring alone in the middle of the roadstead, waiting in vain for a gust of wind that would allow them to attempt a breakaway, the Japanese were in no hurry to attack. They had their prey right where they wanted it. The port of Nagasaki has a shape similar to that of the Bilbao estuary. It is a natural port with a very wide entrance, which empties into an estuary of several kilometers, surrounded by mountains on both shores, with numerous islets in the middle. A site from which ships take time to leave, easy to defend from land and also ideal for laying ambushes. In a word, Pessoa was literally in the lion's den. The first shock occurred after sunset. A flotilla of junks snuck up on the ship under cover of darkness, though the war cries of her crewmen soon broke the silence of the night. The Portuguese prepared their artillery to receive them as necessary, but Pessoa stopped them. He didn't want to be the first to open fire. He gave the order to ignore them and continue with the maneuver to face the mouth of the port. He knew very well that the smartest thing to do if they wanted to keep their skin was to flee from there as soon as possible. The Japanese shots were immediate. A volley of arrows and arquebus fire, which Pessoa very courteously returned with a couple of salvos from his cannon, sounding flutes and drums after each volley for added derision. Unable to stand up to the firepower of an entire galleon, the flotilla could only scatter and return the way they had come. The black ship was a true floating fortress, and although the numbers were on the side of the Japanese, her artillery could not compare with what the Portuguese expended. The night passed, the day came, and still not a miserable breeze blew. Pessoa and his men must have had their nerves on edge. They had spent the entire night in permanent tension, surrounded on all four sides, at a distance where they could practically see the whites of the enemy's eyes. But the Japanese decided to temporize. There were no more attacks that day. In truth, the devastating result of that first clash had left them dismayed. They didn't know how to storm that damned ship without heavy artillery. How to board a ship you can't even get close to?

This deadlock situation lasted several days. By day, the Arima daimyo would send parliamentarians to Pessoa to try to negotiate a surrender. Neither side was very enthusiastic about the task. At night, the assaults followed one another. Wave after wave of junks, laden with armed men, relentlessly charged the flanks of the Madre de Deus. . And they were all rejected with the same virulence as the first night. A storm of fire and iron was brought down with the fury of all the devils of hell on the unfortunates who approached the Portuguese huts. There was no way to break that sea monster. Arima tried everything he could think of. He even sent a couple of samurai disguised to the ship, posing as friars or something similar, so that they could get them on board and assassinate the captain there. But the plan failed. He then sent divers to cut the anchor chain and set the ship adrift, like a commando mission, but that didn't work either. The third night, in desperation, he again launched another frontal attack with a flotilla of fire barges, but the wind dispersed them and only one managed to reach the ship. The crew didn't have too much trouble sending her to the bottom of the sea. The Portuguese were holding up well. They had become strong on their ship and had hardly any serious casualties. But they couldn't resist much longer. Ammunition was running low, and the men's morale was faltering after three days of constant shooting and harassment. For their part, the Japanese did not have them all with them either. In theory they had the upper hand, as time was on their side. But the casualty report was terrifying, and after several days of battle they had made no significant progress. The enemy was still whole and with their firepower intact. Worse than the bullet wounds were the wounds to his pride. The Nagasaki samurai were being humiliated by Pessoa and his 50 sea dogs.

On the morning of January 6, 1610, at last, a favorable breeze made it possible to move the ship. But the streak soon ended and they could not advance beyond an islet near the mouth of the port. Seeing that the prey was about to escape, Arima Harunobu rallied his entire force for a final assault. Reinforcements had arrived in the previous days, and the host numbered a total of 3,000 samurai, with nearly 500 arquebusiers and archers among them. In addition, they had built a kind of assault tower, so large that it had to be mounted on two barges as a catamaran, with which they hoped to be able to board the enemy ship. It was about the same height as the keel of the Mother of Deus , it was covered with wet skins, to protect it from the Portuguese fire, and it had embrasures so that the soldiers could shoot from it and sweep the deck of the Portuguese ship. A far more serious threat than the flimsy reeds Arima had used up to now. Around 8 pm, the Japanese flotilla approached the stern of the carrack, where the Portuguese could only use two mouths of fire to defend themselves. The rest of the guns had been moved to the forward side, to protect the ends of the ship. The commander leading the assault was a Christian samurai, and the warrior ardor with which he conducted himself that day probably had to do with Ieyasu's threat to put every Christian in Nagasaki to the sword if they failed to take that damned ship. The tactic of attacking the weak flank of the ship paid off, and eventually a handful of samurai managed to board her. But the Portuguese, sailors hardened in a thousand battles, were not daunted. Using their swords, they managed to repulse them at once. Captain Pessoa himself, according to the chronicles, finished off two of them in a personal duel. Iberian steel had nothing to envy the legendary Japanese katanas. By sheer force of numbers, little by little, the Japanese were gaining the upper hand. More and more samurai managed to approach the black ship and board it, fighting with their usual contempt for death. But, also true to their custom, the Portuguese managed to keep them at bay. The battle raged, and casualties began to be felt on the Portuguese side. Until fate made an appearance. A Portuguese sailor got ready to throw a grenade but, before he could even release it, bad fortune meant that an arquebus shot hit him squarely and exploded in the middle of the deck. The sparks struck a handful of gunpowder on the ground, setting off a chain reaction that, in the blink of an eye, engulfed the Mother of Deus in flames. . The assailants took advantage of the confusion to board the ship in droves, like a furious mob that devastated everything in its path.

Pessoa and his men hastily retreated to the forecastle, where they fortified themselves and once again tried to repulse the enemy. The captain counted the troops. To his despair, he did not have enough men left to fight the fire and the Japanese at the same time. All was lost. After four days of battle, the flagship of the Portuguese empire was going to fall due to a single shot from an arquebus. In an unusual gesture for an old Christian like him, but which speaks volumes about the honorable warrior of this strong man from the sea, he ordered the magazine to be set on fire and the ship to be blown up. He preferred to go to the bottom of the sea with his ship rather than surrender it to the Japanese. No, they wouldn't take him alive. His second in command hesitated to carry out the order. Then, with a gesture that might as well have come out of an old war chronicle of medieval Japan, Andre Pessoa dropped his sword to the ground, picked up a crucifix in his right hand, and after a brief prayer muttered, he prepared to show his men how. a Portuguese gentleman dies. With two words he said goodbye to his people, ordered them to try to get to safety and descended down the stairs to the cellars, disappearing into the flames. Fue la última vez que se vio al capitán Pessoa con vida. Segundos después, dos terribles explosiones en la santabárbara, casi consecutivas, hicieron volar por los aires lo que quedaba del Madre Deus . El casco se partió en dos y, en cuestión de minutos, se hundió en la bocana del puerto de Nagasaki arrastrando consigo todo su cargamento, a la tripulación y también a los asaltantes que lo habían abordado. Pessoa se había salido con la suya. El enemigo no había conseguido apresar su barco. Su cadáver nunca fue encontrado. Descansa para siempre en las mismas aguas que fueron testigo de su bravata final.

La leyenda de Pessoa y sus bravos

Y llegados a este punto, harto pesar de nuestro corazón, hemos de reconocer que, si bien el relato de los hechos que hemos contado se basa principalmente en fuentes portuguesas, es muy probable que esté un tanto exagerado. ¿Cómo es posible que un puñado de hombres lograra resistir durante días a un ejército entero? Seguramente las cosas no sucedieron exactamente como narran las crónicas que han llegado a nuestros días. Pero hay que tener en cuenta que el as en la manga de los portugueses, su barco, no era moco de pavo. Las naves negras eran la máquina más guerra más formidable del mundo en aquel momento. Una sola de ellas valía casi por una flota entera. Enfrentarse a uno de estos colosos, con su arrolladora potencia de fuego, era como tratar de derribar un destructor imperial de los de Star Wars con un tirachinas. Lo mismo en Asia que en América, el armamento europeo de la época solía ser lo bastante superior tecnológicamente como para anular la ventaja numérica del enemigo.

Por otro lado, las tropas que Arima Harunobu lanzó al abordaje del Madre de Deus estaban lejos de ser lo mejor que Japón podía poner en un campo de batalla en aquel momento. Hablamos de “samuráis” y de “guarnición de Nagasaki”, pero esto tampoco es del todo exacto. Buena parte de estos hombres probablemente no eran ni siquiera tropas regulares. Las crónicas hablan de que Arima tuvo que reclutar gente para organizar el asalto, así que cabe suponer que entre sus filas, además de cierto numero de samuráis bien equipados y adiestrados, habría también un componente importante de wako, ronin y mercenarios de fortuna que se alistaron para la ocasión. Carne de cañón, efectivos de poca calidad, cuyo equipo y armamento dejaba un tanto que desear respecto a los estándares japoneses de la época. La cosa tal vez hubiera sido diferente si, en vez de los Arima, el ejército de un clan más poderoso hubiera estado a cargo de la campaña.

Pero que Andre Pessoa resistió varios días en mitad del puerto de Nagasaki, y que prefirió volar por los aires con su barco antes que rendirlo, son dos hechos incontestables. Y a los japoneses, que no les duelen prendas en reconocer el valor del adversario cuando este se lo merece, el gesto desafiante del fidalgo portugués les tocó la fibra sensible. Pessoa les había dado una hermosa muestra de valor y pundonor. Los valores que los samuráis del momento más respetaban, y que empezaban a escasear entre sus propias filas. Había tenido que venir un tipo del otro lado del mundo a recordarles cómo muere un valiente. Como decían los hidalgos en la jerga de la época, “Antes quebrar que doblar ”. Y vive Dios que Andre Pessoa no dobló.