The Achaean Commonwealth developed into a great power in Greece from the 3rd century BC. Its army, under good command, proved relatively adequate in intra-Hellenic conflicts, but was unable to withstand the mighty Roman war machine. The army of the Achaean Commonwealth initially consisted of divisions of hoplites, conventional cavalry, peltasts and psils. About 275 BC but the army was reorganized on new bases. The Achaean citizens gave up their military attachments and re-armed themselves as shield-bearers, with shield-type shield, long spear, javelins and sword. The elite also carried breastplates (Thorakites).

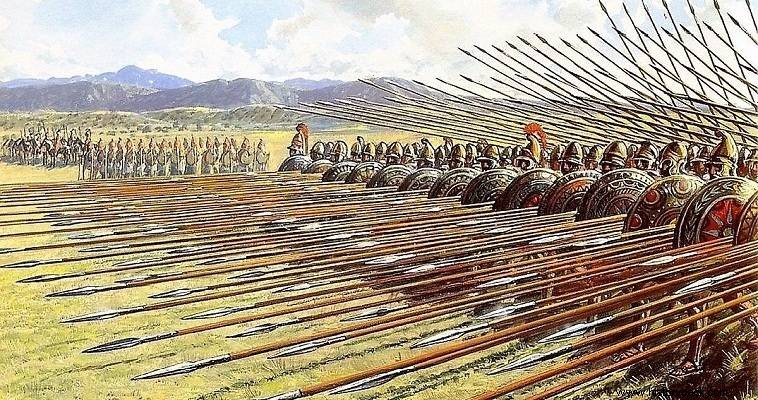

The cavalry, light and heavy, were equipped with javelins and shield. Thus constituted the army of the Commonwealth, under Aratus, suffered a series of defeats by Cleomenes of Sparta. In 207 BC Philopoimen took over as general of the Commonwealth. He reorganized the army by re-equipping the bulk of the infantry with sarissas. The heavy cavalry also abandoned shields and javelins and were equipped with long lances (xyston), simultaneously changing their role from battle cavalry to shock cavalry. The light cavalry was of the Tarantine type, shield-bearing hippocampus. Thus formed, the army of the confederation fought against the Spartan tyrants Mahanidas and Nabi and against the Romans.

The road to the end

In 148 BC the Achaean army was dispersed by the Romans at Scarfia of Phthiotis and the commander of Critolaus fell in the battle. There is no information about this battle, nor about the forces that participated, nor about its evolution. After the death of Critolaus in Scarfeia, the administration was taken over by Zeus from Megalopolis. Zeus, faced with the disaster, proceeded to take emergency measures. First of all, they needed a new army to replace the one destroyed at Scarfeia.

The limited demographic potential of the Commonwealth, however, allowed only limited recruitment. So he decided to order the release of 12,000 slaves, whom he equipped as sarissaphoros and roughly trained as time allowed. At the same time he gathered another 2,000 lighter armed soldiers and just 500 horsemen. This army gathered at Corinth. There the final battle took place. The Roman general Mommius had an army of 23,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry, compared to the 14,500 men that Zeus had managed to gather.

Lefkoptra, the heroic death of a state

The time of crisis finally came in the summer of 146 BC. in Lefkapetra, outside ancient Corinth. There Zeus commanded his army covering his left against the walls of the city, with the phalanx of the sarissaphoros in the center and his few horsemen on his right flank. Mommius also ordered his forces conventionally, with the legions in the center and his horsemen on his left flank, against the few Greek horsemen. The two armies remained thus arrayed the whole day without clashing.

When night fell the Romans retired to rest. Zeus then launched a highly successful night raid against the Roman camp, killing several of the enemy and taking their shields. They were the last enemy shields to fall into the hands of an ancient Greek general, on Greek soil. The Romans panicked but soon rallied and repulsed the invaders. The next day Mommius, enraged, decided to fight the "insolent" Greek general. The two armies faced each other again. The Romans attacked with their infantry. 23,000 legionnaires faced 12,000 phalangites. Then a stubborn battle ensued.

The Romans unleashed their heavy javelins (pila) causing losses to the Greek sarrisophores, but the great depth of their formation did not allow their formation to break up. Every attempt by the Romans to break the phalanx was met with success and each time dozens of Roman corpses remained on the spikes of the Greek saris, overwhelmed. As long as the phalanx had its flanks covered it was impossible for it to be broken by the legionaries. Mommios was in a frenzy. He ordered new attacks but they always had the same result. Zeus, for his part, had every reason to be pleased, keeping the enemy outnumbered and inflicting losses on him.

Then Mommius decided to throw his cavalry into battle. Although outnumbered by 7:1, the Greek horsemen fought heroically and initially managed not only to repel, but also to force the Roman horsemen to retreat. But soon the numerical superiority of the enemy weighed. One after another the Greek horsemen fell, until the few who were left alive fled. The flank of the phalanx was now exposed and Mommius ordered the legions to engage the phalanx in front and his cavalry to flank it. It was the end. The Greek army was disbanded. The men fought to one and fell heroically to their posts. The Army of the Achaean Commonwealth no longer existed. Greece had been occupied.