When recruited to the Polish Legions, and later to the Polish Army, capable peasants hid in barns and forests so that they would not be taken "in sołdaty". Why?

The Rożnowice parish is small - only four villages. (...) When the great war broke out in 1914, as many as ... two peasant sons volunteered for Józef Piłsudski's Polish Legions. In 1920, another volunteer joined the Polish Army. This is a really large number, considering how the soldiers with the eagle on their caps were mistrusted in the countryside . In Galicia it was much better with it than in Congress Poland. The peasants, in the old way, were distrustful, had little national awareness and stood faithfully with the emperor. And one more thing:they listened to their priests in churches, and most of them were against the Legions, because they did not associate them with "national work", but with "the devil incarnate" - socialism (…).

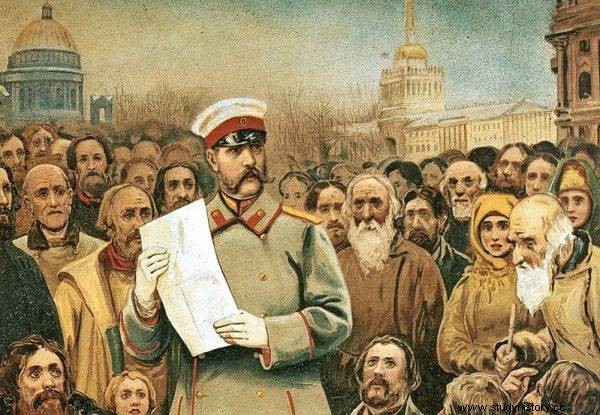

Tsar Alexander II - benefactor of the peasants

Fear of fear, but in the case of both the representatives of the Church and the peasants themselves, it was not the decisive factor here. The legionnaires felt painfully the attitude of the former towards their formation in the most important sanctuary for Poles - Jasna Góra. Władysław Belina-Prażmowski's cavalry squadron stopped in Częstochowa on November 2, 1914. Of course, the uhlans immediately went to the gates of the Jasna Góra monastery to bow down to the Queen of Poland. Unfortunately, they met a severe disappointment. The Pauline Fathers refused to unveil the miraculous image and did not even open the bars to the chapel of Our Lady of Częstochowa (...).

Tsar Alexander II was the greatest benefactor of the peasants and "liberator from the yoke" - Polish, of course.

If even then among the intelligentsia, or more broadly speaking - among the gentry - there were such divisions and doubts about Piłsudski's Legions, then what to say about the peasants, among whom the illiterate constituted a large percentage . And if peasant children in Congress Poland were taught to read in Polish, it was from a primer, a fragment of which was written in his diaries by Jakub Bojko:

God in the sky, Tsar on earth. Without God, the world does not stand, without Cara the earth would not rule itself. One sun shines in the sky, and the Russian Tsar on earth. Prayer to God, and service to the Tsar is not lost. Without Tsar, the land of the widow (…).

In the said reading Tsar Alexander II was the greatest benefactor of the peasants and "liberator from the yoke" - of course Polish . The Polish Legions entering Congress Poland were considered by the majority of peasants to be an integral part of the army of the central states - that is, above all, Germany, and Germany was all evil.

Atrocities of the legionnaires

Stories about atrocities committed by German soldiers in the occupied territories circulated in the villages. These fears were fueled by the official press, as well as by supporters of those political trends who had placed their hopes in Russia. At the same time, the attitude towards the Imperial-Royal Army was more neutral. The peasants simply knew less about Austrians or Hungarians. However, they quickly became as bad as about the Germans, because even if the descriptions of the German occupiers were exaggerated, many of them were confirmed after the congress of Congress Poland.

The order of the day was requisitions, robberies, brutal treatment and coercion to various actions - from giving submarines to carriages to recruiting into workers' teams. These repressions were applied equally by all units, both German and Austro-Hungarian, and it often happened that also legionaries.

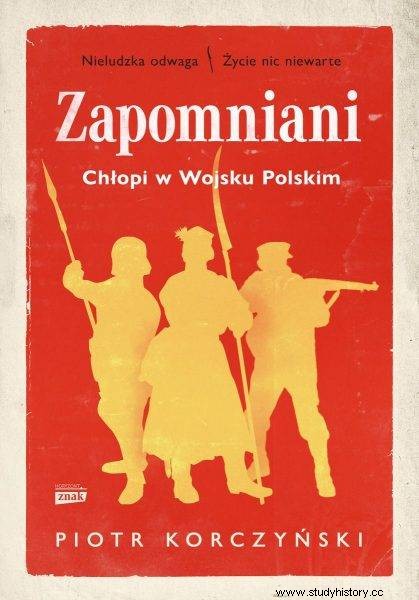

The text is an excerpt from the book by Piotr Korczyński “Forgotten. Peasants in the Polish Army ”, which has just been released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

It is not surprising then that the recruitment campaign for the Legions under the auspices of the Supreme National Committee in the countryside was met at most with indifference and distrust, and sometimes it caused a real panic (...) . The recruiting officer in Opatów, Tadeusz Reger, reported in his report that "wherever we show ourselves, especially in the southern part of the poviat and near the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, a shout is heard:" People running away - the Legions are going! ". Or it was even worse. Jan Hupka, a member of the National Supreme Committee, wrote:"And you often hear from the peasant's lips:« Hey, Mr. Pole, you have to take this eagle off, because when ours comes back, it will be bad »”. "Our", that is, the Russian soldier.

"Socjał" Piłsudski

It took time and a lot of work for this attitude to change. This was slow, which is not surprising given the facts presented, and widespread illiteracy and poverty did not make it easy. In this respect, it was a little better in Galicia, because its autonomy allowed for wider educational work in the countryside, and the popular movement was already established. However, still many peasants called themselves "imperial" or "local" and remained indifferent to the recruitment to the Legions .

In addition, many priests had a negative attitude towards the Legions, as did their colleagues from beyond the cordon. This is evidenced by, for example, the future general and creator of mountain troops in the Second Polish Republic, Andrzej Galica, describing his adventures with priests hostile to Piłsudski's "society" in Podhale, when he recruited highlanders to the Legions. Of course, there were also many, especially among young priests, enthusiasts of gray rifle uniforms, such as the aforementioned father Lenczowski, chaplain of the 2nd Brigade, priest Józef Panaś or priest Stanisław Żytkiewicz from the 1st Brigade.

The same can be said about the effectiveness of recruitment in the Galician countryside - legionary agitation most often went to the few young people who dreamed of a warrior and breaking out of the stagnation of rural everyday life. It was marked by hunger and the lack of prospects, because cutting out a piece of patrimony and vegetation on it for the rest of one's life cannot be regarded as such. It was better to go to war, even under such an uncertain sign as the legionary eagle ... But there were few such "crazy people" in the conservative rural environment, cultivating the memory of those who "went to war with their masters and ended poorly" (...).

Polish army of serfdom

Historians generally describe the attitude of the village towards the rebirth of the Polish state in 1918 as waiting. What's underneath it? First of all, the fear of the unknown or - what is worse - well-known, and still badly associated with peasants. It was not uncommon rumors that serfdom would return to the countryside with the Polish authorities . Those who were glad that "God would deign to give us a free homeland" were treated like village idiots.

What did the new, "Polish, that is, yours" authorities offer after the war? More wars and conscription!

Already in the early days of 1919 with nostalgia were the rule of "good emperors" who "defended the peasants against exploitation and poverty" . And what did the new, "Polish, that is, yours" authorities offer after the war? More wars and conscription! It is not surprising, then, that the villages were filled with one, well-known to officers recruiting peasants, a cry:"You will never wait!".

The highest command of the reborn Polish Army was aware of these sentiments and there was even a conflict in it over the way of carrying out the conscription. Józef Piłsudski, remembering the legion's unhappy experiences in this respect, opted for volunteer enlistment . On the other hand, the Chief of the General Staff, General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, focused on general and compulsory conscription, as it was in the Imperial-Royal army from which he came. The dispute ended with the resignation of Rozwadowski.

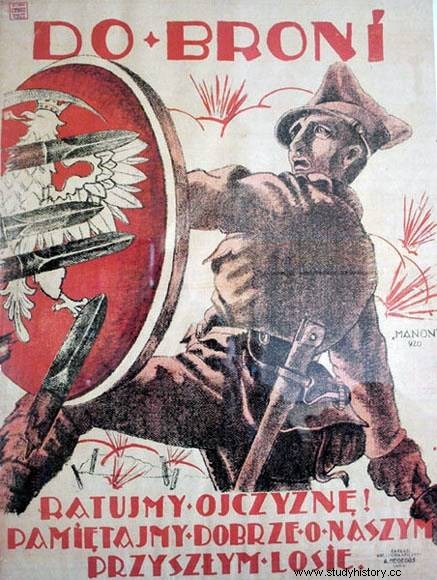

The army was built on the basis of volunteers, but the development of events quickly verified this and it turned out that it was necessary to return to the methods proposed by Rozwadowski. The confrontation with the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Army, which began in 1919, required the Polish Army to also acquire a mass, i.e. peasant, character. Compulsory conscription to the army became inevitable and necessary for the survival of the young state, and this was mainly associated with raising resistance against the invaders in the countryside (...).

Ragged army

The slogan from the propaganda poster: "He takes scythes, throws a plow, has to fight, it is like that", so it repressed the aforementioned exclamation:"Never come!", but of course not entirely, because even in the statement "it happened like this", the fatalism of the peasant's fate was hidden.

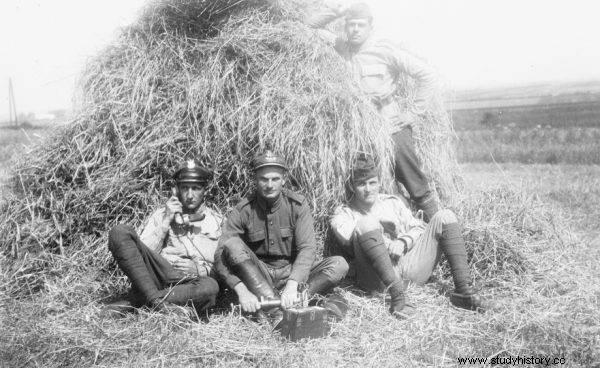

Apart from the lack of national awareness, there were also more prosaic reasons for converging from the ranks of the army. Contrary to popular belief, the provisioning conditions in it did not differ much from those in the enemy. On both sides of the front, soldiers fought barefoot and in rags, holding rifles on strings and worse - hungry and thinned by typhus. It was clearly shown by the Polish-Bolshevik war veteran Stanisław Rembek in the book In the field , which can be treated as not only one of the greatest war novels in Polish literature, but also a testimony of the epoch (...).

The situation required the Polish Army to also acquire a mass, i.e. peasant character.

Stanisław Rembek accurately and vividly portrayed the problems of the Polish army in the spring of 1920 - barefoot and hungry troops, often ineptly commanded by officers , susceptible to communist propaganda and, above all, constantly retreating and failing. Back then, desertions were so common that they began to sneerly be called "Polish holidays".

In August 1920, efforts were made in the Polish Army to solve this problem with methods similar to those used in the Red Army. Behind the line formations there were barrier units with unprotected "bullets"; summary courts passed death sentences on captured deserters, and the military police carried them out immediately; The "uncertain element" was locked up in internment camps. However - as mentioned - the news about the crimes of the Red Army and Chekists in the occupied territories were the most effective encouragement to enlist in the army and remain in it.

Source:

The text is an excerpt from the book by Piotr Korczyński "Forgotten. Peasants in the Polish Army ”, which has just been released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.