According to legends, millions of alleged associates of the devil were burned at the stake in the Middle Ages. The problem is that neither the period in history nor the number of victims agree. So when and - more importantly - how many people actually died as a result of the infamous witch hunts?

It would be an exaggeration to say that in the "dark ages" you could brew magic potions and summon the devil at will, but if the neighbors found someone, in the ninth century in the state of the Franks, for making poison, you were sent to prison for several years or the delinquent was simply expelled from the parish. In Bavaria, a fine of 12 solidi was imposed for the same offense.

And the death penalty? No way! Periodic or lifetime expulsion from the city. This only changed after the Church split at the Reformation, when Church authorities began to become paranoid about "heresy." There were more and more severe sanctions and more and more cruel methods of investigation, and each subsequent sentence proved the rightness of the mission and justified the use of torture . Especially since the latter allowed for a quick admission of guilt, and it was the crowning evidence of conspiracy with the unclean forces.

Don't ask "if" but "when and how"

The theologians and jurists of the time shouted with one voice that witchcraft was the worst and most filthy form of heresy. There were rare voices of reason, such as Michel Montaigne, who wrote bitterly:"We have too much opinion about our guesses, because we are frying people alive by following them."

To be brought to trial, all that was needed was a charge made by an envious neighbor.

The Renaissance brought a real flood of works devoted to devilish practices, which included witchcraft as a conspiracy inspired by the Evil One to destroy the Church. witchcraft . The main author of the book was the influential Alsatian Dominican and inquisitor, Heinrich Kramer, also known as lnstitoris (1430–1505), a godless, cruel and corrupt man condemned by his own order for embezzlement and crimes.

Repeatedly reissued (first published in Poland in 1614), Hammer for Witches became a textbook for inquisitors for the next three centuries. Four features of witchcraft were mentioned in it:rejection of the Catholic faith, devotion of body and spirit to the service of Evil, sacrifice of unbaptized children, and participation in demonic orgies. However, the most fateful thesis of the book was that witchcraft is the natural tendency of women who - inherently gullible and reckless - are more susceptible to the devil's promptings. As we read in the book "Hang, gut and dismember. History of executions ” Jonathan J. Moore:

In patriarchal society at the time, women had very few rights, and anyone who did not live under the official protection of a male was seen as a threat to current norms. In England, under the Tudor rule (1485–1603), economic conditions were particularly harsh, and the following years of very bad harvests left the majority of the population living on the brink of poverty.

One barren pig or cow that fell over and broke its neck could make the difference between life and death for an entire family. Poor diet and poor hygiene translated into chronic health problems. And when any mishap happened, it was very easy to blame a witch for it .

In the years of the greatest intensity of obsession, it was enough for ordinary neighborly envy, unusual interests or minor quirks, or a single inadvertently spoken word, to be accused of witchcraft. There was no defense attorney, the testimony of witnesses in favor of the suspect was not taken into account, and the investigation proceeded according to a set pattern, in which the questions were not "whether" but "how, when and with whom" the devil was worshiped and ungodly acts were committed. What if the "sorcerer" resisted and denied everything? And there were ways of doing that.

How do I get a confession out of a defendant?

Torture, which was the most important element of the investigation against those accused of witchcraft, was of two types. The first group was to prove guilt or innocence through God's judgments - the so-called ordales. The most popular methods included drowning (the guilty did not sink), weighing (the guilty ones were lighter than the Bible on the other side), puncturing (the guilty ones had insensitive and non-bleeding spots), and searching for satanic marks.

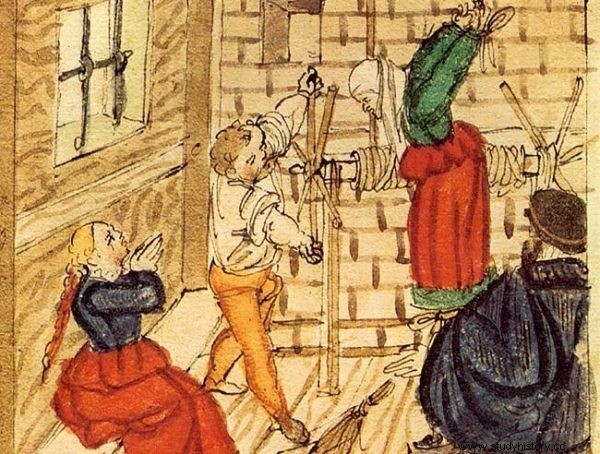

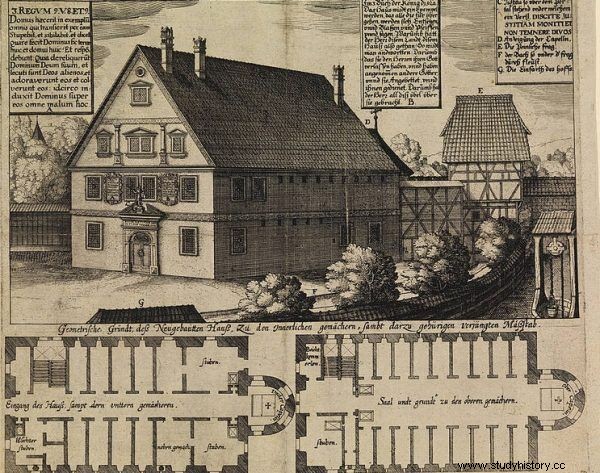

The second type of torture was intended to force the accused to confess and identify the accomplices. In the infamous Drudenhaus - "the witch's house" in Bamberg , for this purpose, among other things, screws were used to crush thumbs and toes, slaked lime tubs, chairs with furnaces for baking the feet or pendulums for suspension . In Poland, the so-called stretching on a ladder, block or bench was most often used. The atrocities on the part of the judges were also of a different nature, as the author of the book writes about, "Hang, gut and dismember. History of executions ” :

The sexually frustrated clergy had a chance to finally go wild. Since women were accused primarily of witchcraft, they often became toys in the hands of their sadistic torturers. (...) All men who were part of the judicial system - from executioners to prison guards to judges - could freely inspect the breasts and private parts of prisoners . Often, on the way to the stake or the gallows, condemned witches were stripped to the waist and their breasts, backs and buttocks were whipped.

Witchcraft suspects were tortured to extract confessions.

Given the cruelty of torture, people were able to admit anything to avoid pain, shorten their suffering or end their lives - the judges had the right, by way of grace, to permit a quick death instead of being burned alive. The mass admission of guilt confirmed the rightness of the proceedings by the authorities. From the 16th to the end of the 18th century, witch trials were held before both church and secular courts.

Map of death

Anyone could end up on the stake, but the most willingly accused were village healers and midwives, widows and single women, shepherds or pharmacists - primarily people who had knowledge of healing and the human body, or those living on the sidelines of the community.

Where was the worst situation for black magic suspects? Contrary to what is commonly believed, not in Spain (except for the Basque Country, witch hunts were stopped there already in the 16th century), nor in Italy, where the Vatican was located. According to estimates most of the witchcraft trials took place in Western and Central Europe .

Catholic Emperor Rudolf II led a long-term and cruel persecution in Austria, and James I in England. Stacks were burning in France, the Netherlands, western Switzerland and Germany. On the territory of the latter lay the notorious Bamberg, where between 1623 and 1633 Bishop Johann Gottfried von Aschhausen burned at the stake several hundred alleged witches, torturing them in the aforementioned "witch's house".

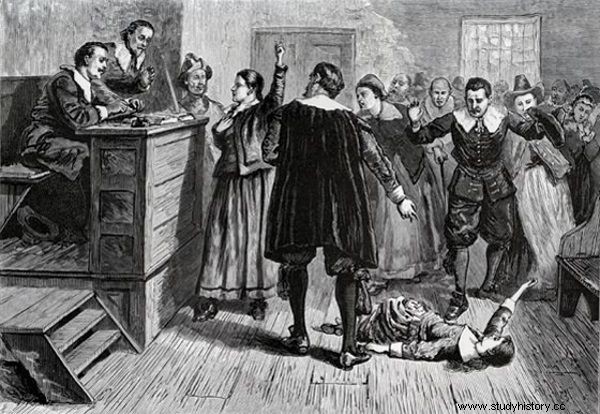

The psychosis of fear of the dark magic was prevalent not only in Europe. Also overseas, alleged witches were tried and killed (in the illustration of the trial in Salem).

And in Poland? Well, the wave of persecution reached us quite late, so in the 16th century foreigners called the country on the Vistula "a state without pyres" . Although the first victim of the campaign was burned alive in 1511 near Poznań, there were very few trials until the end of the century. They did not spread until the 17th century, and the death penalty for witchcraft in Poland was abolished in 1776. Does this mean that our ancestors did not believe in magic? Not at all!

Belief in superstition and superstition was common among both the simple peasants and the educated nobility. Duchess Gryzelda Wiśniowiecka, mother of Michał Korybut, talked about "babes" who confessed under torture that in order to do evil in the Zamoyski family, deceased infants buried in their rooms, which caused infertility to appear in the family. Bazyli Rudomicz, doctor, lawyer, rector of the Zamoyska Academy was also convinced that witches were to blame for his wife's frequent fainting. There were more similar cases.

How to count heaps?

It seems inconceivable that in the then "civilized" Europe, innocent people were burning en masse at the stake. Who was the worst? It's hard to say. English, Scots or Scandinavians were no less cruel than French Catholics or German Lutherans.

The author writes about the terrible Nicholas Rémy (died 1616) from Lorraine, who had 2,500 victims on his conscience, as well as about the bloodthirsty Pierre de Lancre (1553-1631) in the Basque country, whose specialty was forcing children to watch their parents' execution, writes the author books " Hang, gut and dismember. History of executions ” :

The bloodlust had no limits - he accused whole regions, even 30,000 people at once, of dealing with the devil. Reported about a witch coven attended by 100,000 people. He has targeted the Basque country and has killed thousands of Basque women over the course of his career. Eventually he had to flee, pursued by the angry relatives of his victims.

Although the madness gripped most of Europe, there were voices of reason from time to time. Many mayors chased "witch hunters" from the towns and villages - they did not want publicity and avoided trials to keep peace. At Protestant universities, legal commissions were set up to investigate each trial and act as a last resort.

In one of such commissions operating in Leipzig, Christian Thomasius (1655–1728) worked, who in an article from 1712 on the essence of the Inquisition and witch trials stated that under the influence of torture, a man is able to testify anything and acknowledge any charges brought against him.

Two years after the publication, the edict of Prussian king Frederick William put an end to the trials. In the Catholic Church, the Jesuit Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld (1591–1635), author of Cautio Criminalis from 1631, showed a similar voice of reason. In Poland, the Bishop of Kuyavian Florian Czartoryski took the floor, in a pastoral letter of 1657 and a circular of 1669, he called for the cessation of witch trials and expressed his condemnation of torturing suspects.

Anyway, at the beginning of the 17th century, the number of trials was decreasing. In Catholic Spain, the last pyre burned in 1611, in the Netherlands in 1610. In England and Scotland, witchcraft was a crime until 1736, but the last execution was carried out in 1684. In Norway, smoking ceased in 1695.

The witch house in Bamberg, where witch-suspects were brutally interrogated.

In France, where the trials were theoretically ended by the edict of Louis XIV of 1682, it took a little longer, and the last death sentence for engaging in black magic was carried out in 1745, in Germany in 1775, and in Switzerland - in 1782. Eleven years later Poland joined the countries that closed this inglorious stage in the history of Europe .

How many people paid with their lives for blindness and superstition? In the nineteenth century it was believed that ... 9 million, which, however, is far from the truth. Kurt Baschwitz gives a slightly smaller, but still overestimated number, writing:"meticulous estimates oscillate between hundreds of thousands and one million ". Meanwhile, today we know that a total of about 100,000 trials were carried out, and there were a maximum of 40,000 victims, at least half of them in Germany.

And how many piles burned on the Vistula? It is difficult to establish. Bogdan Baranowski states that "from the 16th to the 18th century, in the present-day Polish state, about 20-40,000 women, accused of partnership with Satan, died at the stake or lost their lives as a result of lynching." These are highly inflated estimates - Szymon Wrzesiński writes about several thousand, and foreign researchers say that there could have been even fewer of them - around a thousand. On the scale of the Crown, which had a population of around 10 million, this does not seem to be a particularly impressive number. And yet it's still a thousand too many…