Severe injuries, aggression, extreme brutality and ... human sacrifice. The Maya understood the game of football in a specific way, so it is no wonder that the Church condemned entertainment very quickly. What was the oldest team game ever like?

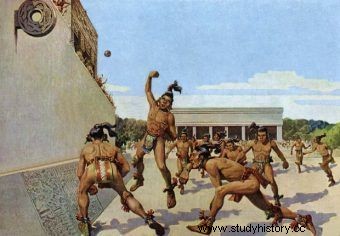

If today the biggest television stations broadcast the games of this game, there would certainly be millions of viewers in front of the TV sets, not only those who love football or basketball - because the ball of the ancient Indians of Mesoamerica was something in between. The game would certainly attract the fans of hand-to-hand combat and aggression to the screens. The struggles of Indian sportsmen were full of both. The game was full of fouls, which today would not qualify for a red card, but for a prison. Very serious injuries also multiplied - broken ribs, knocked out teeth, broken skulls. The 5 kg ball alone could kill, not to mention the game was about life. Those who left the field defeated were sacrificed to the ever bloodthirsty gods.

The Maya and Aztec gods were hungry for blood

The conquistadors who started their conquest of America in the 16th century came into contact with the Indian ball. The ritual of playing ullamaliztli, as it was called during the Aztec times, was fiercely stigmatized by the Catholic Church as a pagan superstition.

The ancient Olmec people are considered to be the creators of the ullamaliztli. The oldest "Indian ball" pitch was built in the Mazatan area in today's state of Chiapas, Mexico. They date back to 1700-1550 BC. The oldest rubber ball for this game, discovered by archaeologists, is around 3,000 years old.

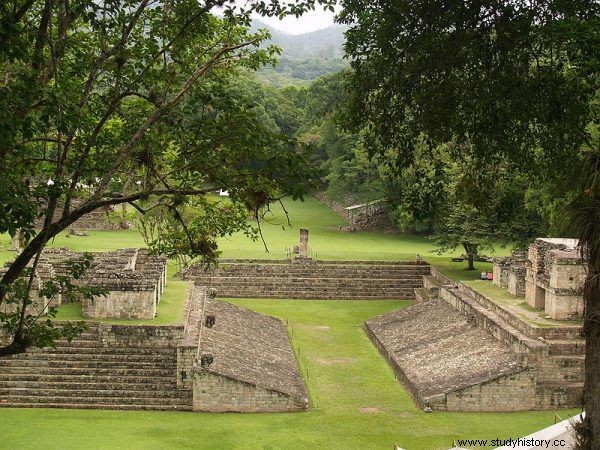

Playgrounds were built in city centers, at main squares and temples. Like today, they were turf and rectangular in shape. They were more narrowed and rather smaller than modern playing fields, although there were also very large playing fields:the largest - in the ancient city of Chichén Itzá, measured 166 meters in length and 68 meters in width. At the long ends, there were straight or oblique stone walls that the ball bounced off during the game. Vertical stone "gates" or "baskets" - rings with a diameter of about 90 centimeters were placed on the walls. The players' task was to throw the ball through a hoop suspended several meters above the ground (even 6 meters).

Hipball…

Neither Diego's divine hand, nor Messi's left foot, insured for $ 80 million, would have had any meaning in the game of the ancient Indians, because the rubber "gala" was suitable for movement of the hips and thighs. The specific rules made the players on the pitch squirm in bizarre poses and shake their hips like a samba, but in practice it was very difficult to throw the ball this way through the stone hoops.

Since the ball could not hit the ground after one allowed hit, players often had to perform dangerous, but spectacular slides, thanks to which the rubber ball remained in the air. Bouncing with buttocks, knees, and in some variants with elbows was also allowed. The feet and hands were not allowed to "play" however.

Chichén Itzá - a stone ring on the ullamaliztli pitch

There were usually two to four players in a team. We don't know the scoring rules. Probably getting the ball through the hoop, as extremely difficult, was an instant win.

The struggle forcing to the strangest positions, tackles and other acrobatics, with a fierce course, had to be full of injuries, fractures, sprains and brutal fouls, even with elbows. Certainly during matches that could last many hours, blood was spilled. In order to avoid fractures and injuries, the players used special hip protectors made of leather, wood and even stone. They protected against injuries, but also allowed to bounce the ball harder.

The Mayan game could be called ... a hipster

Spanish clerics have reported its great weight, but also exceptional elasticity. It bounced much better than air-filled balls. Unfortunately, because of this and because of its weight, the ball itself could crush or kill a player during the game, as reported by New World chroniclers. It happened that an Indian who was hit in the head or belly fell lifeless to the ground. The game's injury was also confirmed by archaeological research. Scientists found skeletons of players with broken limbs, hipbones or shoulders.

The ending of the match was also bloody. Until today, however, scientists have not decided for whom:losers or winners ...

Athlete sacrifice

The gods of Central America wanted human blood. Each activity in the world there had a ritual dimension, it was subject to a calendar that strictly defined the meaning of each day. Every important event had to be "sealed" with a sacrifice to the gods, a human sacrifice. It was no different with the matches in ullamaliztli.

Scientists agree that athletes who played hipsters often faced death on the sacrificial altar. The bloody rites in America did not always affect only enemies, convicts or prisoners. After all, that's how the gods were worshiped. Therefore, it is unclear if it was not the winners who voluntarily and smiling (often anesthetized with narcotic substances) went to their deaths with a smile on their face.

Copán - ullamaliztli pitch

In Chichén Itzá, the execution of a soccer player is depicted on a relief carved into a stone wall. You can see the player's head beheaded, but it is not known if he belonged to the winners or the losers.

Perhaps it was fluid, depending on the political context and situation. For example, if the game took place after a victorious battle and the opposing team were prisoners from a hostile tribe, the match was more propaganda than sporting. It was used to bring back the won clash. There was no doubt about who would cut off his head or tear his heart out on a sacrificial stone. As a rule, they had to lose the prisoners, which is why they were starved and even broken before the match. There was no question of fair play.

Sometimes the stakes of the match grew sky-high, because it happened that the rubber ball game replaced the actual battles. The winning team represented one of the sides in the conflict, and the victory on the pitch gave concrete political benefits.

Religion and sport

What, in a significant way, distinguishes Indian football from today's football or basketball, but also from the gladiatorial struggles in Rome, is the fact that the matches probably did not have the character of a public show. The pitches for playing in ullamaliztli did not have dedicated places strictly for the audience, like the Roman arenas. So probably the struggle was watched by a small group of spectators, probably priests, because the game was ritualistic.

The ulama player from Sinaloa

On the stone hoops, there was often an image of a serpent, referring to Quetzalcoatl - a feathered serpent, the most important deity of the Aztecs and Mayans (Kukulkan). Probably, the game was a kind of thanksgiving to the deity, and the throwing of the ball was a symbolic creation of the world anew, guaranteeing success, abundance of crops, etc.

The Church, seeing only barbarism and the pagan rite of cruel rivalry, condemned the practice of ancient sports, but despite the struggle with old customs, the Indian ball in a mild and somewhat folklore form has survived to this day. It is now called ulama and is popular in some parts of Mexico. Thus, the hipsters competition is perhaps the oldest team game in the world, with a history reaching 4,000 years.

Bibliography:

- Renata Faron-Bartels:People and gods of Central America, Ossolineum, Wrocław 2009

- Curt Wilhelm Ceram:The first American. Warsaw:State Publishing Institute, 1977

- Timothy Laughton:Maya. Life, Legends and Art, National Geografic, G + RBA Publishing House, Warsaw 2002

- Wojciech Lpioński, History of Sport, Warsaw 2012

- Tadeusz Łepkowski:History of Mexico, Wrocław [etc.]:Ossolineum, 1986

- Jane McIntosh:Treasure hunters. Lost and found treasures of the world. Warsaw:G + J RBA Sp. z o.o. &What. Limited partnership, 2001

- Justyna Olko:Mexico before the conquest, PIW, Warsaw 2010

- Wiesław Konrad Osterloff:Before the Spaniards Came, Warsaw 1968

- Bernardino de Sahagún:A thing from the history of New Spain, Marek Derewiecki Publishing House, Kęty 2007

- Dennis Tedlock:Popol Vuh, Book of the Maya, HELION Publishing House, Gliwice 1996