Bread with the consistency of concrete. Pseudo-chocolate beetroot cut with a knife. And one candy a year. Discover the assortment of shops operating at the mercy of the Nazis.

In Krakow, the Germans launched a card system on November 13, 1939. In Warsaw - only on December 15. Food rationing was intended to provide every Pole with at least the minimum ration needed to survive.

As long as the idea itself was correct - indeed, one could even say that the Nazis showed off their humanitarianism! - its realization seemed like a gloomy joke.

Our sheet bread

The basic product sold on cards was bread, the daily ration of which, after initial turbulence, was between 150 and 300 grams per person .

Due to the ingredients used in its production, card bread was much heavier than the bread we eat every day in the 21st century. Clay, black, bitter, crumbling. Each of these adjectives was used to describe the occupation "wholemeal", but they cannot reflect the taste and health benefits of this bread.

Food distribution during the occupation

Maria Kwiatkowska from the vicinity of Bielsko, who was a teenager during the occupation, recalled that he was called quite a specific name.

There was no baking bread in the new flat. We were given cards for bread […]. The bread was called "sound" because it was black and sour and caused gas.

This term must have been popular because it appears in various war diaries. A writer and member of the Home Army, Aleksander Maliszewski, after more than twenty years, still remembered that:

every Pole had the right to buy 25 decagrams of sound engineer, i.e. loaf bread, a day for each page.

In turn, in the book Retaliation , by Jerzy Duracz, there is a humorous exchange of sentences:“You've got so much hog fat in the war? Margarine, sound maker and marmalade! ”.

Bread for cards was also called "clay", "card", "bonovce" or "granola" (from "vouchers" or cards). He could be a "governor" (probably in reference to the unlovingly reigning Hans Frank), a "sad" or finally a "coke oven" - because he looked more like a bad sort of coal than bread.

Concrete marmalade and candle-flavored margarine

Another must-see on the card shopping list was marmalade made of… something. Not the pre-war recipe, apples with cinnamon, clear and aromatic. There was something completely alien to the Polish pre-war taste on the shelves of switchgear stores.

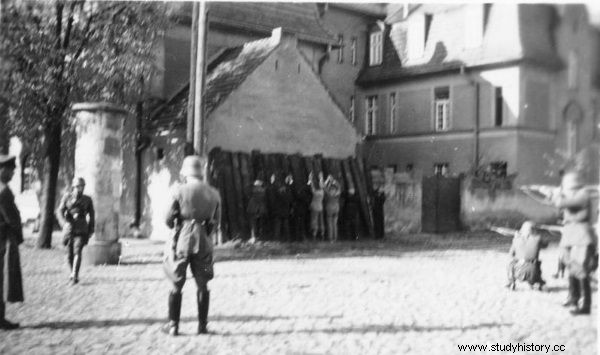

Hans Frank decided that starving Poles would keep them in check. In the photo, Frank is walking among the forced laborers.

Marmalade with a watery or, on the contrary, a concrete consistency. Or rather, pseudo-chocolate, because beetroot paste and other equally attractive fillers were added to it.

The Germans argued that it was an excellent quality product, made of pure fruit and 50 percent sugar. Similar, misleading claims were common. The occupying authorities quickly mastered propaganda.

Poles, however, simply knew and saw theirs. You had to buy this strange specific dish with your own vessel. No matter how it tasted or what was in it.

Real debauchery!

For hungry people, only the days when they were able to get their rations of bread, marmalade, margarine and flour were sometimes joyful.

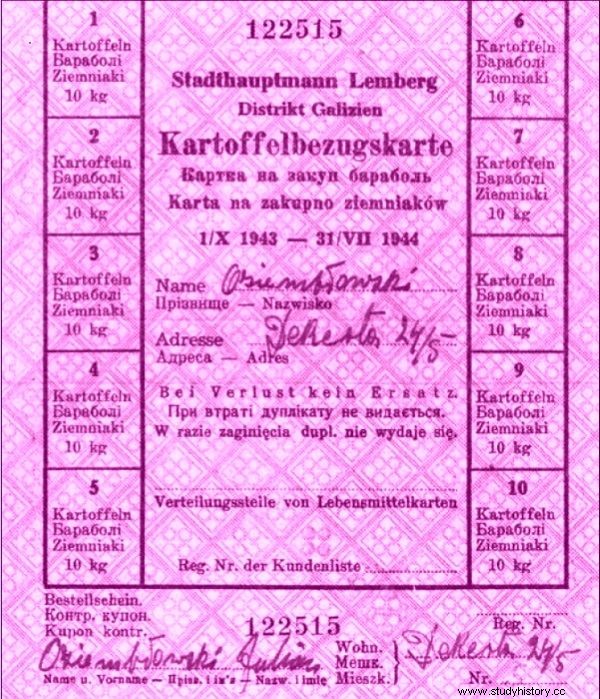

A set of cards for potatoes.

Born in 1935, Hanna Wolska remembered well what this card rarity looked like:

I went with my mother, I saw it, there was marmalade in large blocks, but similar to beetroot. I ask:"Mummy, this marmalade is the color of beetroots, but it is so pretty, because the beetroot is round and you cook the beetroot soup, and here the shop assistant is cutting with a knife".

There were fats as well. During the war and occupation, many an adult Pole forgot what real butter tastes like, because if he managed to get it, he would give it to children. And what was the taste of the assigned margarine? Wojciech Jursz, a Warsaw insurgent, put it bluntly:"German margarine - as if he were eating a candle".

Some people preferred to replace it somehow and put onions fried in oil on the bread. In fact, they didn't have much choice.

The average family ate a slice of bread, spread with margarine or marmalade.

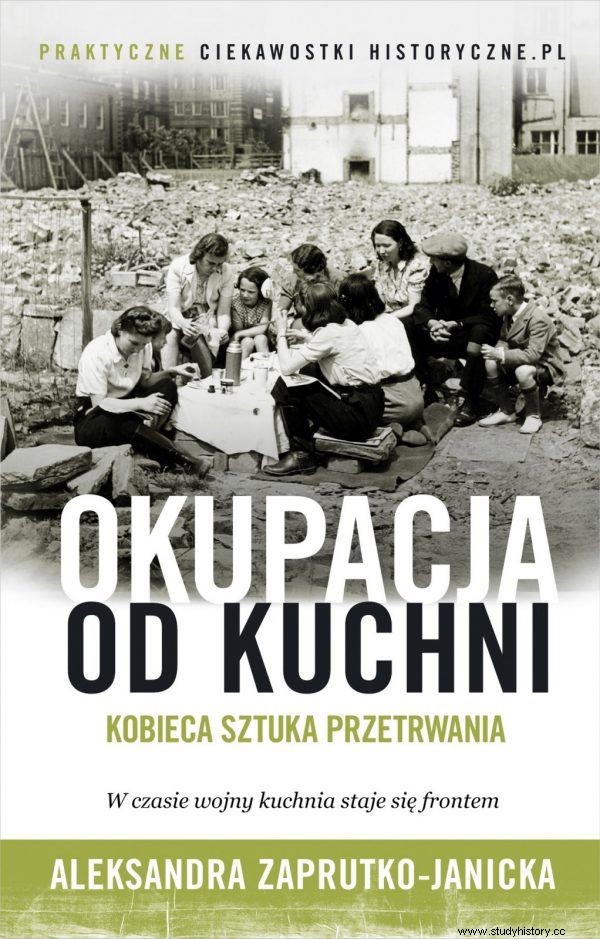

The female art of survival in Aleksandra Zaprutko-Janicka's book "Occupation from the kitchen". Click and buy with a discount on empik.com .

Both were not used at the same time. "Oh no, this is debauchery" - Danuta Kalińska-Łaszkiewicz's mother, the headmistress of a private school before the war, replied to her daughter's request for a slice with margarine and marmalade.

In symbolic amounts, sugar and wheat flour were also issued on the cards. Meat for non-German people existed mainly on paper. Even if a microscopic batch happened to be thrown into stores, it was always of poor quality. Something the Nazis would be ashamed to give to those they considered to be full-fledged people.

In addition, cards for pasta, groats and coffee substitutes were allocated. Several times during the war it was also possible to get a voucher for sweets or biscuits for children.

The Germans had just enough of them so that the Poles, giving their daughter or son their first candy in years, could envy them about being Aryans. And by the way - to successfully pretend to the world that they provide new subjects with everything necessary for a comfortable life.

Marmalade making machine.

The truth was quite different. If someone wanted to eat only what was legally received from the assignment, he would not have a chance to survive until the end of the war. It was not a rationing system. The Nazis deliberately starved not only Warsaw, but the entire Polish society.

Let them starve!

The card system did not provide even the minimum necessary food. And it doesn't matter what the theory presented. First of all, the days when all voucher products could be purchased at the distribution store were rare.

Even in the case of great luck and realizing all weekly food stamps, there was no point in getting ready for the feast. Exactly how much food did Poles get in a typical seven days? Detailed calculations are provided by Bogdan Kroll in the book Rada Główna Opiekuńcza 1939−1945 .

From January 1941 to September 1943, the allocations were very poor, taking into account the slight regional fluctuations and shortages.

When Poles tried to get food outside the legal circulation and engaged in black market activities, they risked being shot.

An adult received an average of 2 kilograms of potatoes, 1 kilogram of bread, 10 decagrams of flour (about cup), 5 to 10 decagrams of meat and its products, 5 to 10 decagrams of sugar, 5 to 10 decagrams of marmalade, 4 decagrams of grain coffee, ¼ to ½ of eggs and a minimum amount of salt.

The assignments were independent of gender and profession. Only a few fortunate ones, employed in plants of key importance for German industry, could count on some extras. Others were condemned to vegetate.

Children up to the age of 14 received even smaller rations of bread. In October 1943, the allowances were slightly increased to 1.5 kilograms of bread, 12.5 decagrams of sugar, 12.5 decagrams of marmalade, and 20 decagrams of pasta and groats. These increases were simultaneously taking part of the rations from landless villagers. Allocations did not stay at this level for long.

As early as mid-1944, the Germans began to drastically lower them. The Reich suffered defeat after defeat in the East. In Berlin, Poles never really cared for survival, but then they stopped even thinking about keeping their appearances.

Significantly, it was difficult to see fat Poles on the streets of the city.

The "grace" of the master race

League of Nations experts established in 1936 that a person who does not perform physical work must consume 2,400 calories a day for his body to function properly. If he works physically, there should be an additional 300 calories for each hour of work. Compared to these figures, the energy value of the allocations for the population of the General Government was downright dramatic.

According to the data of the Central Welfare Council (RGO), quoted by Krolla, daily card food provided an average of 400–600 calories for adults and 350–550 calories for children. After these standards were raised in 1943, calories increased to 800 for adults and 500 for children.

If Poles had acted in accordance with Nazi law and rely only on the food grace of the Germans, there could be only one result:in the cities, no one would survive. And although the situation was by no means funny, it is one of the cutthroat jokes that perfectly illustrates the prose of life of the time:

- What are you standing for? - Franek Antka asks.

- But you see:I have to "buy cards"!

- What are you holding the potty for?

- Because they will give shit anyway!

***

The article was based on materials collected by the author while writing the book "Occupation from the kitchen". Click and buy your copy at empik.com with a discount.

"Okupacja od Kuchni" is a moving story about the times when illegal pig slaughtering could lead to Auschwitz, vegetables were grown in the courtyards of tenement houses, and used coffee grounds were traded on the black market. It is also an amazing cookbook:full of original recipes and practical tips from 1939-1945. We recommend!