Skip, skeiô, knörr…. It had been a hundred years since a Viking grave ship had been discovered in Norway. Detected in 2018, the one in Gjellestad is starting to tell its story.

2021 archaeological excavations of the Viking ship-grave of Gjellenstad (9th century), Norway.

Was its prow adorned with horses and dogs? Were tracery of stylized monsters carved into the ship's hull? Or dragon heads? Since 1904 and the discovery of the Oseberg Ship (9th century), no Viking ship had been excavated in Norway. Hence, at the end of 2021, this feeling of pride experienced by Scandinavian archaeologists after their last brushstroke on the bow of the one found buried in Gjellestad, not far from Halden, in the south-east of the Norway. It had been discovered buried under a tumulus in the fall of 2018 thanks to surveys carried out using ground-penetrating radar (GPR).

Image released on October 15, 2018 by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Research (Niku), showing the outlines of a Viking ship identified by georadar, near Halden, Norway. Credits:Niku/AFP

Image released on October 15, 2018 by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Research (Niku), showing the outlines of a Viking ship identified by georadar, near Halden, Norway. Credits:Niku/AFP

This boat had been buried around the year 800 according to the Viking custom of burial of certain chiefs

His study has just been completed. Under the grassy curves of a mound 32 m in diameter, this boat had been buried around the year 800, according to the Viking burial custom of certain chiefs. Transported on logs from a nearby river, the boat had been deposited at the bottom of a dug pit. A heavy task that had to federate the intervention of a large number of people, perhaps slaves (traells) . The installation of a funeral chamber was then erected on the boat to accommodate the remains of the deceased. Ceremonies were probably performed before the whole was covered with a thick layer of earth arranged in such a way that it did not crush the ship. Then the centuries passed. Time has done its work… and so have looters.

Excavation of Viking ship Gjellestad by Norwegian archaeologists, October 2020. Credits:Marghrethe K.H. Havgar

Excavation of Viking ship Gjellestad by Norwegian archaeologists, October 2020. Credits:Marghrethe K.H. Havgar

The boat having been found in an advanced state of degradation, Christian Lochsen Rodsud, a researcher at the University of Oslo, has constantly accelerated the work so that the greatest amount of information is collected before any disappear under the destructive advance of microscopic fungi. Head of the Gjellestad ship excavation project, he ensured that all the remains were extracted in the form of blocks of earth, to then be carefully analyzed in the laboratories of the National History Museum in Oslo, in the heart of the capital.

One of the blocks of earth brought from Gjellestad to the National Museum in Oslo (November), for laboratory excavations. Credits:Kulturhistorisk museum.

On the ground were extracted fragments of iron and copper alloy found in the burial chamber, coffer elements as well as fittings, and hundreds of nails and rivets from the clapboard assemblies of the hull…”The location of each nail has been meticulously positioned to preserve the structure of the ship and allow its reconstruction in 3D ", explains Christian Lochsen Rodsud, joined by Sciences et Avenir .

Protection of nails and rivets discovered on ship's hull. Credits:Marghrethe K.H. Havgar

Protection of nails and rivets discovered on ship's hull. Credits:Marghrethe K.H. Havgar

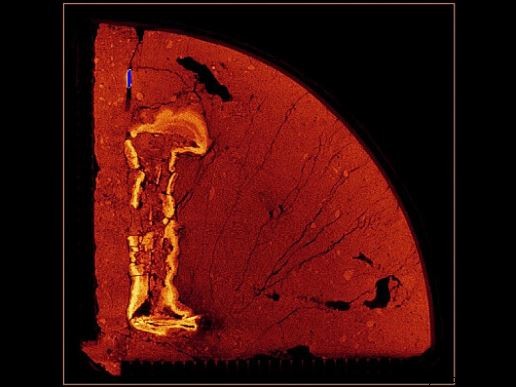

Analogously to the Viking ships of Oseberg and Gokstad (read box ), everything was also robbed. "Despite this, we were able to collect a lot of clues ", specifies the archaeologist. In the burial chamber, a quantity of horse teeth was thus collected, as well as 560 bovine bones and calcined human bones. "We had already encountered cases of animal decapitations in other burial remains of the Viking elite", continues Christian Lochsen Rodsud. Foremost among the finds that surprised archaeologists was the coniferous wood used for the ship's floor, instead of the expected oak, and the rusty imprint of a large ax laid under the hull. Were these ritual relics? The block of sediment that contained it will soon be scanned and X-rayed.

X-rayed iron rivet in its dirt matrix. Credits:Kulturhistorisk museum

X-rayed iron rivet in its dirt matrix. Credits:Kulturhistorisk museum

Christian Lochsen Rodsud adds:"For us, the most important thing is the overall documentation of the ship. It will allow us to create a digital model of all the remains, which will later serve as the basis for its reconstruction. We still have years work ahead of us with the analysis of material brought back to the Museum of Natural History in Oslo. Findings by X-ray and CT scans, preservation of artifacts and remains of the ship to come are among our research priorities ".

Among the finds is a huge amber bead that may not be a case unique. Credits:Kultuhistorisk museum.

Among the finds is a huge amber bead that may not be a case unique. Credits:Kultuhistorisk museum.

Surprises are indeed expected during laboratory analyses. Colored pearls have thus been glimpsed hidden in certain blocks of sediment which will soon be examined. One of them, a huge amber bead, has already been extracted. "It could be a sword bead ", according to the Norwegian archaeologist. Fascinated for a long time by the amber to which they lent protective virtues, the Vikings like their predecessors adorned their swords with these pearls. Attached to the scabbard by a cord, they acted like a charm. Those recovered in the Gjellestad ship may have served to protect the deceased on his journey to Valhalla, the paradise of Viking warriors.

The Oseberg and Gokstad burial ships

Until the Gjellestad ship in 2018, only two Viking burial ships had been unearthed in Norway. That of Gokstad, in Sandar, by Nicolay Nicolaysen, in 1880 and that of Oseberg, 21m long, by Gabriel Gustafson, in 1904. The first, which must have been used for offshore navigation, was the tomb of a man, near which were exhumed the remains of two peacocks and two birds of prey. Outside the ship lay twelve horses and seven dogs.

The Oseberg Ship, one of the few preserved Viking ships currently on display at the "Viking Ship Museum " in Oslo, Norway. Credits:AFP

The Oseberg Ship, one of the few preserved Viking ships currently on display at the "Viking Ship Museum " in Oslo, Norway. Credits:AFP

As for the Oseberg tomb ship, it yielded impressive remains, including fifteen horses, four dogs, two oxen, sleds and an immense quantity of organic material, including precious textiles.

The Oseberg ship, at the time of its discovery in 1904. Credits:AFP

The Oseberg ship, at the time of its discovery in 1904. Credits:AFP

In 1948, the bones of two high-ranking women were also found there. These characters were possibly related to the first king of Norway, Harald the Fair Haired. In the case of possible interpretations of the use of boats in Scandinavian funerary customs is the idea of helping to transport the dead to the afterlife. Alignments of naviform stones have gradually replaced these real boats as graves over time.