Ethiopia is asking France for help to keep Lalibela, famous for its medieval rock-hewn churches. Its 3D modeling reveals the history of the construction of the site, as explained in this article taken from Sciences et Avenir 845 (July 2017).

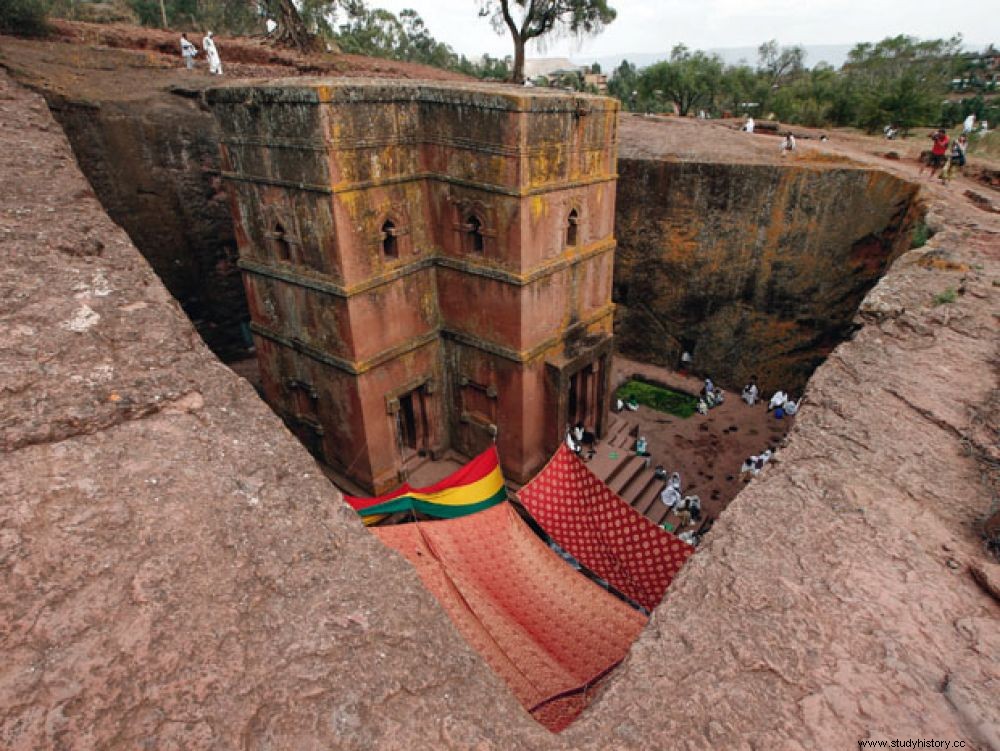

Bete Giyorgis, one of 11 Orthodox buildings carved into the volcanic rock at Lalibela, rises some 12m inside a pit. Tunnels allow the faithful to move from one church to another.

While Emmanuel Macron is in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa has asked France to support him in safeguarding a symbol of Ethiopia's millennial history:the rock churches of Lalibela. On this occasion, we invite you to read the article that our journalist Bernadette Arnaud had devoted to "Black Jerusalem", it was in Sciences et Avenir 845, of July 2017.

Bete Danaghel, Beta Golgota-Selassie, Bete Medhane Alem, Bete Gebriel-Rufael (Saints-Gabriel-et-Raphaël)… or even the most famous cruciform Bete Giyorgis (Saint-Georges). For almost 800 years, thousands of pilgrims have visited the cave churches of Lalibela each year, carved into the basalt 500 km north of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. There, on the high plateaus, 2600 meters above sea level, wrapped in their gabi white, they come to pray in “Black Jerusalem”, this major site of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, one of the oldest Christian denominations in the world (IV e century) (read the box opposite) . This exceptional site of around twenty hectares, classified as a World Heritage Site by Unesco in 1978, is the subject of an unprecedented study carried out by a French team which is trying to retrace its history. .

"We had no data on the construction of these monolithic religious buildings ", explains Marie-Laure Dérat, research director at the CNRS (UMR 8171), at the head of the project "Lalibela, archeology of a rock site", co-directed by Claire Bosc-Tiéssé (CNRS) and supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. foreign institutions, the CNRS, Inrap and Unesco. Objective:to reveal the different stages of construction of the 11 churches which sink to a depth of 12 meters and whose origin, according to tradition, dates back to King Gebre Mesqel Lalibela, a ruler of the 13th th century. In full expansion of Islam, it would indeed have liked Ethiopian Christians to be able to gather in a symbolic portion of the Holy Land, Jerusalem being difficult to access for them since its reconquest by the Muslims in 1187. “ The precise chronology was very difficult to establish, for lack of archaeological remains “, continues Marie-Laure Dérat. The researchers therefore called on the Archéovision laboratory in Bordeaux, the CNRS' technological platform specializing in the modeling of archaeological projects.

Different periods of digging

The use of 3D has thus made it possible to reconstruct the site in its various stages of excavation, to propose its digital reconstruction and, therefore, to facilitate the development of hypotheses on its construction. A first phase of troglodyte dwellings has thus been revealed by the researchers, who place it around the X e -XI e century. Quarriers would then have undertaken to dig the volcanic rock starting from its summit and hollowing it out as the descent progresses. They would thus have pierced galleries. Examination of burials in a cemetery contemporary with these very first arrangements has helped researchers to understand that they were the work of a society practicing non-Christian rites, without it being known who these arrangements served. . “It is only from the XII th century that the site of Lalibela was transformed into a religious complex as we know it today adds Marie-Laure Dérat. The builders then penetrated deeper into the ground to drill, from the inside, the vast halls with columns reserved for the reception of pilgrims. The existing galleries and pillars were then incorporated into the churches.

To better understand these phases of construction, the specialists also studied the evolution of the liturgy observed by the clergy of the time. "The Ethiopians were indeed inspired by the architectural program of the churches of Egypt to build theirs “, continues the archaeologist. When Islam arrived on the banks of the Nile, at the end of the 7th th century, Coptic Christians found themselves unable to build new churches. They then multiplied the sanctuaries inside those that already existed.

A hidden room where sacred texts are kept

Although not having to suffer from these restrictions, the Orthodox Christians of Ethiopia, very close to those of Egypt, therefore proceeded in the same way. With one difference:the presence of a "sanctuary", the most secret room of Ethiopian churches, where priests and deacons officiate out of sight of the faithful. This is where the sacred texts and the tabot, a replica of the Ark of the Covenant described in the Bible, are kept. According to legend, this sacred chest - believed to contain the Tablets of the Law given to Moses on Mount Sinai - was stolen from Israel by the first king of Ethiopia, Menelik, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. A mythical filiation to which the very believing monarch of Lalibela was attached by his dynastic affiliation. Even today, a troglodyte church is being excavated in the Lalibela region.

LOCATION

The first Christians, Greek traders

Before taking the name of Ethiopia in the IV

e

century, the Kingdom of Aksum was a center of trade between the Eastern Mediterranean, the Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean. This is how Greek-speaking Christian traders began to settle on these shores of the Red Sea. Along with their counters, they erected churches. Legend has it that a man named Trumens, survivor of a shipwreck on the Ethiopian coast in the IV

e

century, would have been appointed first bishop of Ethiopia by the Christian authorities of Egypt to whom he had reported the existence of this nascent church.