Researchers and experts have long agreed that the origin of the Great Flood myth found in many cultures of the Mediterranean and the Near and Middle East lies in the Mesopotamian story told in the Gilgamesh poem, which includes a version of the story that is actually older.

It is tablet number XI that contains the flood myth, which was copied by the scribe, for the most part, from an earlier poem, the Atrahasis . Interestingly, the copy of this that has survived is later than that of the Gilgamesh poem.

The story tells how Atrahasis, whom the Babylonians called Utnapishtim and the Sumerians knew as Ziusudra, survived the great flood by building a ship in which he embarked his family and a couple of each type of animal. In Gilgamesh's poem, the hero visits Utnapishtim and he tells him this story and how he achieved immortality, which Gilgamesh also pursues.

Between 1963 and 1989, the site of Abu Salabikh, the ruins of a small Mesopotamian city that flourished in the middle of the third millennium BC, was excavated in Iraq. It is located about 20 kilometers northwest of the site of ancient Nippur. First it was the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and since 1975 the British School of Archeology in Iraq who took charge of the work.

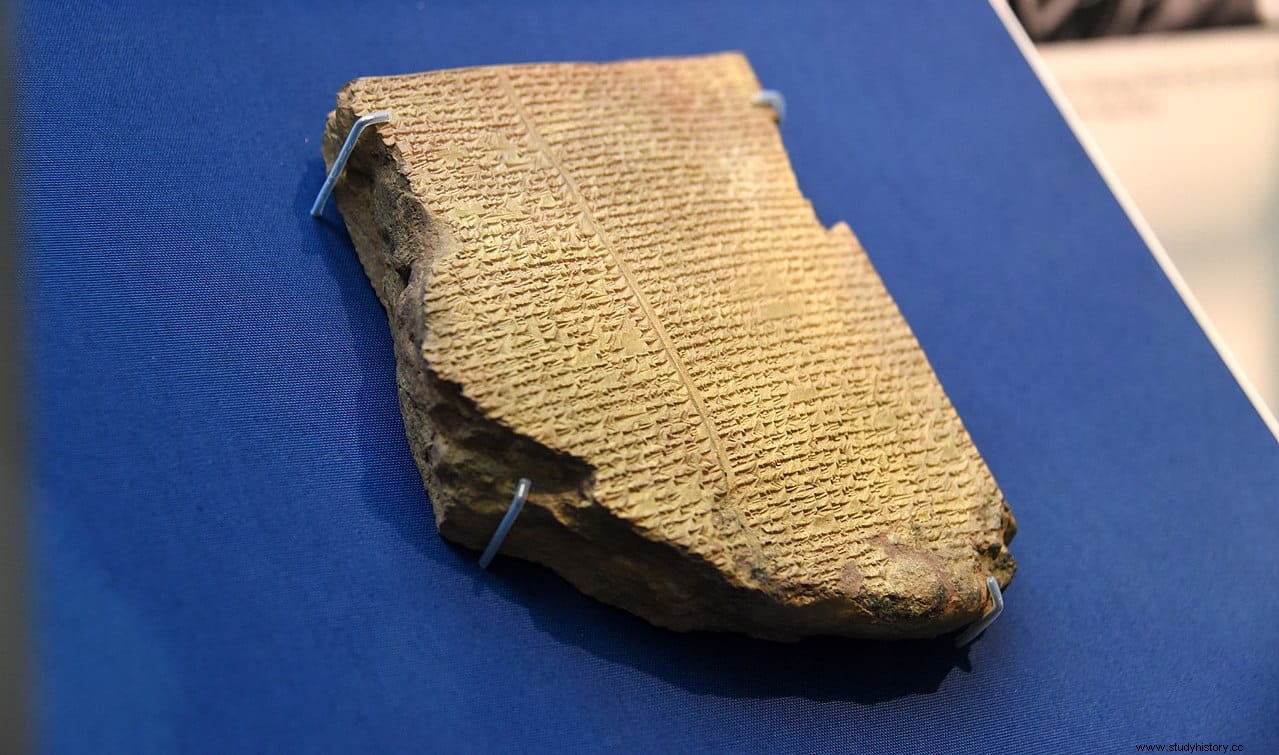

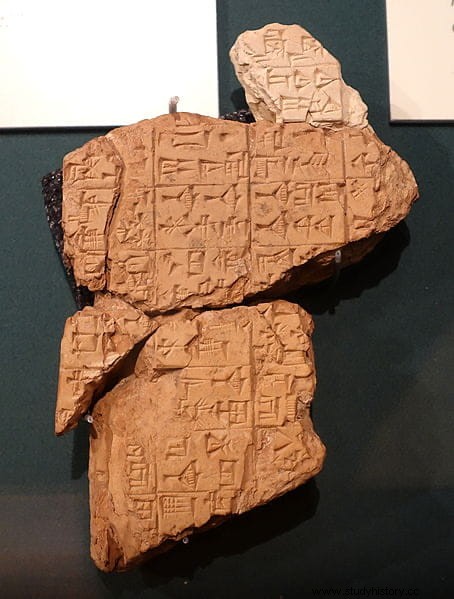

Among the finds made were more than 500 tablets with cuneiform writing, mostly school texts, but also some with poems, hymns and proverbs, which are among the oldest texts of Mesopotamian literature. One such tablet is the one containing the Shuruppak Instructions .

It is a compilation of precepts and exhortations that Shuruppak addresses to his son Ziusudra, who is none other than the Babylonian Utnapishtim and the Akkadian Atrahasis who will eventually become the hero of the flood. The Instructions they date from the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, and are among the oldest surviving literature.

In turn, Shuruppak may be a patronymic rather than a proper name, as this is how one of the five cities was known. antediluvian of the Sumerian tradition. He was the son of Ubara-Tutu, who is recorded in most extant copies of the Sumerian king list as the last king of Sumer before the deluge (he is also briefly mentioned in the Poem of Gilgamesh tablet XI). /p>

This tablet found at Abu Salabikh is the oldest extant copy of the Instructions , but numerous later copies have been found, indicating that it was a very popular text within the Sumero-Akkadian literary canons. One such later copy was found as early as 1904 in Bismaya (Adab) by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

As for its content, it is advice from a father to his son for the welfare of the kingdom, his family and himself, along the same lines as the later Egyptian Instructions of Amenemope. It is divided into three parts, each beginning with an exhortation.

Some of Shuruppak's advice is eminently practical:

But there are also moral precepts:

In general, they include precepts that are common to all Mesopotamian wisdom literature, including some that will later appear reflected in the Ten Commandments and in the Biblical Book of Proverbs. The words must not appear up to 64 times.

The text is repetitive and recursive, something typical of the oral tradition. The tablets found have made it possible to translate a large part of the Instructions , but the lack of snippets means that we are still missing important parts of the text.

As for who wrote it, the text itself indicates that it was written by a servant named Nisaba, and that it was dictated to her by Shuruppak, son of Ubara-Tutu for his son Ziusudra. Nisaba was the Sumerian goddess of fertility, calligraphy, and astrology.