The French Foreign Legion is one of the most famous corps in military history, which has truly written indelible pages of glory on all the battlefields of the world, from Europe, to the ends of the Sahara, Mexico, Indochina, Madagascar. And yet the Legion had rather "humble" origins.

The Foreign Legion it was originally formed as an expendable unit, staffed by the dregs of the French Army and by European adventurers. Its genesis is identified with the formation of the French colonial policy, of which the Legion would be a part. However, the reason for its formation was initially political. In July 1830, a revolt broke out in Paris against the royal Bourbon dynasty.

The Swiss and other mercenaries who supported the dynasty were demobilized immediately after the happy for the rebels ended the revolution. Thus a large number of soldiers were left "unemployed", turning into criminals, just to survive. This fact combined with France's colonial aspirations in North Africa gave birth to the Legion.

The dregs of France

The French Army had a centuries-old tradition of having large numbers of mercenaries in its ranks. Throughout the reign of the Valois and the Bourbons, the French Army deployed a large number of Swiss and German mercenaries, who were also the most elite units of the army. This practice continued until 1789 when the French rebels massacred Louis XVI's Swiss mercenaries.

Nevertheless, the new regime, as well as the Napoleonic empire that succeeded it, continued to recruit mercenaries. The defeat and fall of Napoleon restored the Bourbon dynasty to the throne of France. The kings reorganized the mercenary corps, among them the Swiss Guard, but also the predecessor of the Legion, the Hohenlohe Regiment. The latter was formed in 1815 under the name of the Royal Foreign Legion.

The supposed "German" regiment included in its ranks men from Germany, Switzerland, Poland, Italy and Spain as well. Naturally the mercenaries, especially the Swiss Guards, were not popular with the French, who saw them as a support of the hated monarchy.

After all, between 1827 and 1830 there were many conflicts between mercenaries and French citizens. In November 1828, a real battle broke out between the Swiss Guard Regiment and the French 2nd Grenadier Regiment, with many dead on both sides.

Finally, on July 30, the revolution broke out and the French people won King Louis-Philippe's promise to grant a constitution and disband the mercenary corps. First the Swiss regiments were disbanded and then the Hohenloh regiment, which was initially proposed to be sent to Greece, together with General Maison's expeditionary force. On January 5, however, it was dissolved. A portion of his men were naturalized French and joined the 21st Light Infantry Regiment. But most of them were left without money and without food even in Marseilles.

The "unemployed soldiers" gradually began to create new problems for the French state. They formed groups and carried out attacks on the shops, in order to secure the necessary bread. Under the pressure of this fact the French king had to find a way to "empty" his country of the now intruding foreigners.

France as early as May 1830 had been involved in a war with the Algerian beys and had conquered a narrow coastal strip of land on the North African coast. There the conflicts with the indomitable Arabs, as well as the climate, were permanent sources of bleeding for the French divisions. Then the idea was born. The "intruders" could be assigned to a new body, "expendable", and sent to Algeria to deal with the Arabs.

Thus, French blood would be spared and the "unemployed" mercenaries would be freed. With this in mind, the king signed on March 10, 1831 the founding act of the Foreign Legion, according to which men aged 18 to 40 could enlist in it and serve France.

Initially, the decree did not specify that those enlisted in the Legion should be exclusively foreigners, and so many French unemployed, impoverished workers, thieves and others tried to enlist, dreaming of a new start, but also a very "spoilt" one in exotic Africa.

In the face of this development a new royal decree was issued, which forbade French citizens to join the Legion. The latter, however, circumvented this by declaring Swiss or Belgian citizenship to the recruiters. Besides, the Legion was for many of them the last refuge, in which they could hide from the law that persecuted them for their illegalities. The Legion did not ask questions about their past, a tradition that lasted for many years.

Those assigned to the Legion were initially placed in various camps at Langres, Bar-le-Duc, Auxerre and Agen. But there were no officers and non-commissioned officers to train them. The revolution of 1830 had also caused a crisis in the army and resulted in the demobilization of 60% of the senior officers. The solution was provided by the reinstatement of veteran officers of the Napoleonic Wars. But even they did not wish to join the body of the "intruders".

Commissioning in the Legion was seen as a punishment for French officers. And indeed the military minister, Napoleon's old comrade-in-arms, Field Marshal Schultz, ordered his officers with the worst "file" to join the Legion.

Thus the "scum" of society would be governed by the "scum" of the army. What could one expect from such a body, but to be slaughtered by the Arabs, relieving France of the responsibility of feeding the men yet!

The first commander of the Legion was the Swiss Colonel Baron Christopher Stoffel, who informed Schulz in a letter that of the 26 officers he had sent him, only 8 were fit for service.

Stoffel asked for the dispatch of good officers, who should be conversant in German. The administration, however, was not particularly interested, although it eventually sent 107 Swiss, German and Polish ex-soldiers to take up the duties of officers and non-commissioned officers in the new corps. But the situation was about to get worse.

The Legion, in addition to being understaffed, and consequently undertrained, did not even have sufficient food for its men, many of whom began to sell their personal belongings to secure a morsel of bread. In response, the administration imprisoned them.

Many died of starvation there, as, under the law at the time, the prison administration was not required to feed military prisoners. The army had to ensure their food.

But the army "forgot" to do so, with the result that many elites got rich and many legionnaires died! Naturally such behavior caused a riot, which was quelled with the help of the gendarmerie. On the other hand, the authorities, fearing new riots, decided to send the Legion an hour earlier to Africa, to get rid of it once and for all.

The Legion was gradually transferred to Africa in the second half of 1831. First, Colonel Stoffel landed in Algeria in charge of two battalions. The Legion settled in its first "home", where for years it would act glorifying France.

The first contact with the desert

The legionnaires must have seen the sun-burnt Algiers for the first time with excitement and anticipation. After what they had suffered they had arrived in their own Promised Land, hoping for a better future. And indeed the image from the ships promised this. But when they landed the dreams were shattered.

Algiers, which had been captured by the French just a year before, had suffered great damage from the battle. However, it retained something of its exoticism, with its brick-built houses and its fortress where the tricolor French flag flew.

The Arab inhabitants, always restless, under their bored gaze, the white adventurers and traders, composed an unusual scene for the legionnaires. Underneath this fake idyllic image, however, war was hidden, a cruel and merciless war. The French had managed to capture only a few coastal towns on the North African coast, not daring to move inland, securing vital space for their possessions.

The Legion would play a large part in the expansion of the French and would be the corps that would conquer and defend its conquests, for the "glory" of France. Algiers, the Legion's first station in Africa, was essentially a besieged city, with the French confined behind the old walls.

In the first phase, it was decided to build small forts around the city, in order to lift its unofficial siege. The legionnaires participated in the construction of the fortifications and then in their guarding. But service in these isolated strongholds was extremely difficult.

The Arabs cut off the small, isolated garrisons, depriving them even of water, while they did not fail to attack them at every opportunity. The Legion, along with the newly formed bodies of the Zouaves and the Hunters of Africa, paid a heavy price during the construction of the forts, but also afterwards by guarding them. The Legion fought and won its first battle on April 7, 1832, when two of its companies intercepted an Arab attack.

On May 23, however, the first calamity would come. Major Solomon de Moucy, at the head of 27 legionaries and 25 light cavalry, was moving towards the fort of Maison Carré, which guarded the eastern approaches to the city of Algiers.

Suddenly the detachment was attacked by a large group of Arabs. The major ordered the legionnaires to defend themselves in a small forest, placing the Swiss lieutenant Sam in charge. He and the horsemen left to "bring help". Of course the 27 legionnaires and the Swiss lieutenant had no hope.

After fighting desperately for some time, they were surrounded and killed or captured. But the captives were also all executed when they refused to convert to Islam. Only one legionnaire, the German Wagner, converted to Mohammedanism and escaped with his life. After 13 days he managed to escape and arrived at Maison Carré and reported the events.

The "brave" major was then expelled from the Legion and killed fighting in 1836, head of a disciplinary department. But in the meantime the Legion was growing. The political crisis that had broken out in Europe, but also the Polish revolution against the Russians and the Belgian revolution against the Dutch, had the effect of thickening the ranks of the Legion.

Thus, in the inspection of December 1, 1832, the Legion was found to line up 3,168 legionnaires, included in six battalions. Shortly after, a seventh battalion was also formed. Of these men 87 were French, 94 Swiss, 571 Italian, 98 Belgian and Dutch, 19 Swedish and Danish, 10 British, 85 Polish and 2,196 German. Of these, about 800 were to die or be demobilized over the next three years from the cholera that was plaguing Europe and Africa at the time.

In 1833, out of the 2,600 legionnaires in Algiers, 1,600 were hospitalized, or more correctly, simply lying in the hospital, without being provided with essential care. On the other hand, the behavior of the French authorities had not substantially improved in relation to the legionnaires.

The latter were once again deprived of even food. However, the sick legionnaires were in a more tragic fate, who were not entitled to food, which they would have to pay for themselves.

So many of them were forced to work, sick, to earn a pittance or sell their personal items. In the latter case, if the legionnaire escaped death by cholera, he often faced the firing squad or forced labor.

The legionnaire Prenio became famous because he escaped with only two months of imprisonment, having sold, while in hospital, his boots, gaiters and grain hopper, in order to procure food!

The life of the legionnaires in Algeria was by all accounts hard. Even simple guard duty at one of the regional outposts meant for the legionnaires a death sentence from disease. The marshes around the city of Algiers were centers of contamination. It was thus decided to desiccate them, a task also assigned to the Legion. These conditions decimated the Legion. There was a case where an entire battalion was taken out of service due to illness.

A natural result was that the Legion suffered from low morale, the consequence of which was frequent desertions. But the problem for a deserted legionnaire was where to take refuge. The Arabs, and because of the difference in religion, did not gladly accept the European deserters, unless they converted to Islam. On the other hand, returning to Europe was even more difficult.

So many legionnaires preferred the Arabs. As a countermeasure the Legion command adopted another measure, the pseudo-deserters. In such a case, Sergeant Miller and a legionnaire were sent to make contact with the Arabs, in order to arrange for their "defection".

When everything was arranged the two "deserters" moved towards the rendezvous point, covered by a detachment of the Legion. The Arabs and other real deserters who rushed to meet them fell into the trap and in the ensuing conflict at least 70 Arabs and deserters were killed.

However, legionnaires continued to suffer, dying in hospitals, or during what were essentially forced labor. They rarely faced the Arabs on the battlefield.

They were "expendable" and they knew it! In the same period, the Legion changed its commander three times. In June 1832 Stoffel was replaced by the Frenchman Kobet, who also delivered the first battle flags to the Legion. But he too was replaced very soon by Colonel Bernay.

Apart from the first skirmish at Maison Carre, the Legion was not involved in serious conflicts. In November 1832, its units took part in the victorious battle of Sidi Chambal, but also in skirmishes in the area of Cape Bon.

In 1833, the Legion participated in the skirmishes in Arzev and Mostagienem. In 1835, however, the Legion fought its first major battle. Sheikh Abdul el Kader had managed to unite under his command the Bedouin tribes south of Oran and turn them against the French.

The battle of Makta

In response the French command sent a mixed brigade, under General Trezel, to suppress the rebellion. Trezel's forces also included three companies of the Polish 4th Battalion of the Legion and the entire Italian 5th Battalion, under Lt. Col. Conrad. Trezel had two more battalions of infantry, four companies of light cavalry (African Hunters), some light guns and several transports. On the morning of June 25, the French phalanx set out to meet the enemy.

Trezel had formed his forces in a quadrilateral, with the Polish companies and two islands in the vanguard, the Italian battalion on the left flank and the rest of his forces on the other sides of the quadrilateral.

The French formation crossed the "forest" of Mullah Ismail, an area of a few palm trees and low vegetation, which extended to the edges of a small range of hills near the streams of Sig and Treblat. Suddenly the vanguard began to receive sporadic fire from Arabs covered in vegetation.

The three Polish companies were then ordered to attack and overthrow the Arab acrobolists. The legionnaires indeed attacked, overthrew, and pursued the opposing acrobolists, only to receive in turn the charge of a strong, reserve body of Arabs.

The legionnaires retreated fighting and joined the main body. Trezel then ordered his cavalry to intervene. The "African Hunters" attacked but were repulsed and when their colonel was also killed they retreated in disorder. Η υποχώρηση του ιππικού μέσω των τάξεων του πεζικού προκάλεσε, όπως ήταν φυσικό αταξία.

Ιδιαίτερη σύγχυση προκάλεσε η σάλπιγγα του ιππικού που σήμαινε την υποχώρηση. Τα μεταγωγικά, που βρίσκονταν στο κέντρο του τετραπλεύρου, ανταποκρινόμενα στο κέλευσμα της σάλπιγγας, άρχισαν να υποχωρούν, διαλύοντας την συνοχή του σχηματισμού.

Ο Τρεζέλ διέταξε το 5ο Τάγμα της Λεγεώνας να αντεπιτεθεί στους Άραβες, οι οποίοι επιτίθονταν τώρα μανιωδώς στα απροστάτευτα μεταγωγικά. Μαζί με ένα τάγμα του 66ου Συντάγματος Πεζικού , οι λεγεωνάριοι πράγματι κατόρθωσαν να αποκρούσουν τους Άραβες και να σώσουν τα περισσότερα μεταγωγικά.

Τελικώς έως το μεσημέρι η γαλλική φάλαγγα κατόρθωσε να ανατρέψει τις αραβικές αντιστάσεις και να διασχίσει το «δάσος». Είχε ήδη όμως υποστεί μεγάλη φθορά – 52 νεκροί, 180 τραυματίες. Υπ’ αυτές τις συνθήκες, λαμβάνοντας υπόψη του και την ιδία ανεπάρκεια, ο Τρεζέλ, όφειλε να ακυρώσει την αποστολή και να επιστρέψει πίσω. Αντί αυτού όμως συνέχισε την πορεία του και την επομένη στρατοπέδευσε δίπλα στο ρέμα του Σιγκ. Από εκεί προσπάθησε ανεπιτυχώς να έρεθει σε διαπραγματεύσεις με τον Άραβα ηγέτη ελ Καντέρ.

Ο ελ Καντέρ αντί απαντήσεως, υποχώρησε ακόμα βαθύτερα στην έρημο με τις δυνάμεις του, επιθυμώντας να παρασύρει τον Τρεζέλ σε παγίδα. Και ο Γάλλος συνεργάστηκε άψογα. Το πρωί της 28ης Ιουνίου ο Τρεζέλ διέταξε τις δυνάμεις του να κινηθούν και πάλι. Αυτή τη φορά έταξε το 4ο Τάγμα της Λεγεώνας στο δεξιό πλευρό και το 5ο Τάγμα στο δεξιό. Καθ’ όλη τη διάρκεια της πορείας τους έβλεπαν Άραβες ιππείς να τους παρακολουθούν από απόσταση ασφαλείας.

Ήταν βέβαιο ότι ο ελ Καντέρ γνώριζε τις κινήσεις τους και τους περίμενε. Ο Τρεζέλ όμως επέμεινε για συνεχίσει τις «επιθέσεις». Γύρω στις 14.00 η γαλλική φάλαγγα έφτασε σε μια περιοχή, με τα έλη της Μακτά εμπρός και τη λοφοσειρά Μουλά Ισμαήλ πίσω. Η θέση ήταν ιδανική για την παγίδα του ελ Καντέρ.

Πραγματικά ο Άραβας ηγέτης εκεί ακριβώς περίμενε τους Γάλλους. Σε λίγο οι φρικτές πολεμικές ιαχές των φανατικών πολεμιστών του γέμισαν την ατμόσφαιρα. Χιλιάδες Άραβες, πεζοί και ιππείς ρίχθηκαν κατά της γαλλικής φάλαγγας από δύο αρχικά κατευθύνσεις.

Ο Τρεζέλ, φοβούμενος καταστροφή των μεταγωγικών του, έδωσε διαταγή στο 5ο Τάγμα να τα υπερασπισθεί. Η θέση των Ιταλών λεγεωνάριων όμως σύντομα κατέστη τραγική, εφόσον εντελώς ακάλυπτοι δέχονταν τα πυρά των Αράβων.

Ο αντισυνταγματάρχης Κόνραντ επενέβη τότε προσωπικά και οδήγησε το 5ο Τάγμα στην επίθεση, εκκαθαρίζοντας τους Άραβες. Σύντομα όμως το τάγμα βρέθηκε μπροστά σε έναν ανεξάντλητο αριθμό Αράβων και αναγκάστηκε να υποχωρήσει. Η υποχώρηση των λεγεωνάριων όμως προκάλεσε πανικό στο 66ο Σύνταγμα, οι άνδρες του οποίου τράπηκαν σε φυγή.

Ακολούθησε πανικός, καθώς οι Άραβες, εκμεταλλευόμενοι και την κατεύθυνση του ανέμου, έβαλαν φωτιά στα χαμόκλαδα. Απειλούμενοι να καούν ζωντανοί, οι λεγεωνάριοι, με τον αντισυνταγματάρχη Κόνραντ επικεφαλής, υποχώρησαν όλοι σε ένα μικρό λόφο. Οι Άραβες τότε κατέστρεψαν τα μεταγωγικά και σκότωσαν τους οδηγούς και τους τραυματίες. Ο Τρεζέλ, που μάταια προσπάθησε να ανασυγκροτήσει το 66ο Σύνταγμα, τέθηκε επικεφαλής δύο ίλες ιππικού και προσπάθησε να αντεπιτεθεί.

Αποκρούστηκε όμως και αναγκάστηκε να καταφύγει στις θέσεις των λεγεωνάριων, των μόνων, μαζί με τους πυροβολητές του, που δεν είχαν τραπεί σε φυγή. Από τις θέσεις τους στον λόφο οι λεγεωνάριοι απέκρουσαν, με την ενίσχυση των πυρών του πυροβολικού, τις αραβικές επιθέσεις. Τελικώς τα υπολείμματα της φάλαγγας Τρεζέλ έφτασαν στο Οράν.

Η ήττα στη θέση Μακτά είχε στοιχίσει 342 νεκρούς και αγνοούμενους και 300 τραυματίες, ένας εκ των οποίων ήταν και ο ανθυπολοχαγός της Λεγεώνας Αχιλλέας Μπαζαίν, ο μετέπειτα αρχηγός στρατού. Η ήττα στη Μακτά είχε ως βασικό υπεύθυνο τον Τρεζέλ φυσικά, ο οποίος οδήγησε τους άνδρες σε έτοιμη παγίδα. Παρόλα αυτά ο ίδιος μετακύλησε τις ευθύνες του στον Κόνραντ, κατηγορώντας παράλληλα και τους λεγεωνάριους για δειλία.

Η μάχη ωστόσο είχε καταδείξει πράγματι και αδυναμίες της Λεγεώνας. Η μεγαλύτερη αυτών ήταν το «εθνικιστικό» πνεύμα των μονάδων, που είχε ως αποτέλεσμα τη ελλιπή μεταξύ τους συνεργασία. Έτσι αποφασίστηκε να διαλυθούν τα «εθνικά» τάγματα και να οργανωθούν μικτά.

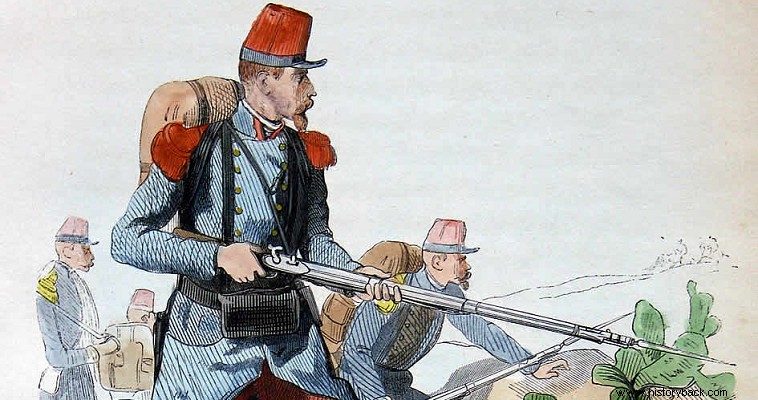

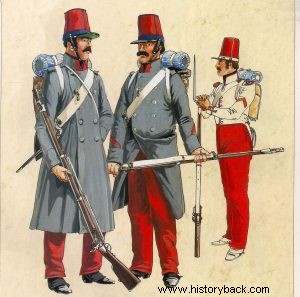

Λεγεωνάριοι στην Αλγερία το 1832.