Hiro Onoda, born March 19, 1922 (Taisho Era 11) in Kamekawa Village (now Kainan City) in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, and died January 16, 2014, was a Japanese soldier stationed on the island of Lubang in the Philippines who refused to believe in the end of World War II and the surrender of Japan in 1945 and who continued the war alone until 1974. He is the best known many "hidden" Japanese soldiers.

Military training

Coming from a family of six brothers and sisters, Hiro Onoda studied at Kainan College. At 17, he joined the import-export company Tajima-Yoko, specializing in the sale of varnishes in Wakayama, then asked to be assigned to a branch of the company in Hankou, China. At the age of 20, he was called up for his military service to join the 61st infantry regiment of Wakayama. Shortly after, Onoda was assigned to the 218th Infantry Regiment:destination Nanchang, where he reunited with his brother Tadao.

In 1943, Onoda arrives in Kurume, which has a school with a fearsome reputation under General Shigetoumi. After three months of intensive training, Onoda returns to his original unit. On August 13, 1944, Onoda left Kurume to join the 33rd company in Futamata, which was an annex of the Nakano school in which commando officers were trained. In December 1944, Onoda was one of twenty-two men trained in guerrilla techniques. Destination:the Philippines, an American territory occupied by Japan. His superior, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, gives him the order to delay the landing of the Americans on the island of Lubang, on which Hiro Onoda will spend more than thirty years in the jungle awaiting the return of the Japanese army.

1945-1974

In 1945, American troops retook the island and nearly all Japanese troops were wiped out or taken prisoner. However, Onoda continued the war, first living in the mountains with three comrades (Yuichi Akatsu, Siochi Shimada, and Kinshichi Kozuka). One of them, Akatsu, finally surrendered to Philippine forces in 1950, and the other two were killed in crossfire with local forces – Shimada in 1954, Kozuka in 1972 – leaving Onoda alone on the mountain.

He dismissed as a ruse any attempt to convince him that the war was over. In 1959, he was declared legally dead in Japan.

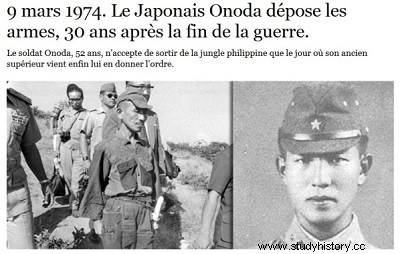

Found by a Japanese student, Norio Suzuki, Onoda stubbornly refused to accept the idea that the war was over unless he had received the order from his superior to lay down his arms. To help him, Suzuki returned to Japan with photos of himself and Onoda as proof of their meeting. In 1974, the Japanese government was able to find the commander of Onoda, Major Taniguchi, who had become a bookseller. He went to Lubang, informed Onoda of Japan's defeat and ordered him to lay down his arms. Lieutenant Onoda left the jungle 29 years after the end of World War II, and accepted his commander's order to hand over his uniform and sword, along with his Arisaka Type 99 rifle still in working order, five hundred rounds and several hand grenades.

Although he killed about 30 Filipinos who lived on the island and exchanged several gunshots with the police, the circumstances were taken into account and Onoda was granted a pardon by President Ferdinand Marcos.

Lieutenant Onoda was, strictly speaking, the last soldier of Japanese nationality to surrender. The very last soldier of the Japanese army was found a few months later, in December 1974:it was not a question of a Japanese citizen, but of an aborigine of Taiwan, incorporated in the volunteers of Takasago under the name of Teruo Nakamura.

Afterlife

After his surrender, Hiro Onoda moved to Brazil, where he became a cattle rancher. Shortly after his surrender, he published an autobiography, Not to Surrender:My Thirty Years War, in which he describes his life as a maquisard in a war that had long since ended. Subsequently, he married a compatriot and returned to live in Japan in 1984 where he created a camp for children in the middle of nature. There, Hiro Onoda shared with them what he had learned about survival during his years of solitary living. In 1996, he returned to visit Lubang Island and donated ten thousand US dollars for the local school.

Onoda was affiliated with the very influential and openly revisionist Nippon Kaigi lobby, which aims for the restoration of Empire and militarism.

He died on January 16, 2014 in Tokyo.

Notoriety

His story inspired several screenwriters. It is partly taken up in the film Hello friend, goodbye treasure with Bud Spencer and Terence Hill and in the episode A corner of paradise of the series Agence Acapulco. The comedy The Last Flight of Noah's Ark (1980) also features two Japanese soldiers who believe they are still at war on a lost island. We can also note the presence of forgotten Australian soldiers from the Second World War, on the fictitious island of Solomon, in the novel The Island of Living Fossils by André Massepain.

Onoda can be seen referenced, briefly, in the very first minutes of Pierre Schoendoerffer's film Le Crabe-Tambour (1977), as medical major Pierre (played by Claude Rich) watches the television news aboard the escort ship French Navy squadron the Jauréguiberry.

In the field of video games, this story is found in the game Just Cause 2 where there is an island populated by old Japanese soldiers who refuse to believe that the war is over.

A spaceship in Xavier Mauméjean's novel The Special War takes up his name.