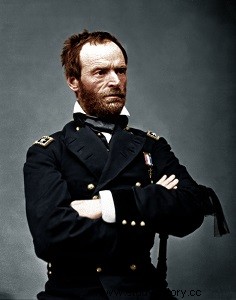

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, teacher, and writer. He served as a general in the Union Army during the Civil War, where his skills as an officer and strategist were recognized. But he is also widely criticized for his harsh scorched earth policy and the all-out war he is waging against the Confederate States.

In 1862 and 1863, Sherman served under General Ulysses S. Grant in the campaigns that led to the fall of Confederate Fort Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, and resulted in the rout of the Confederate armies in the state of Tennessee. In 1864, Sherman succeeded Grant as commander of the Union Army in the Western Theater of the Civil War. He leads his troops in the capture of Atlanta, a military success that contributes to the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln. Later, Sherman's march through Georgia and the Carolinas campaign further undermined the Confederacy's ability to continue fighting. He secured the surrender of all Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865.

When Grant became president, Sherman succeeded him as commanding general of the United States Army (1869 - 1883). His role led him to lead the Indian Wars in the American West. His career was marked by a constant refusal to engage in politics, and in 1875 he published Memoirs, one of the best-known direct accounts of the American Civil War. Analyzing Sherman's military career, military historian Liddell Hart calls him "the first modern general."

Youth and family

William Tecumseh Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio, on the banks of the Hocking River. His father Charles Robert Sherman, a brilliant lawyer who sits on the Supreme Court of Ohio, names him after the famous Tecumseh, leader of the Shawnee Native American people. Judge Sherman died suddenly in 1829, leaving his widow, Mary Hoyt Sherman, and his eleven children without an inheritance. Nine-year-old William Tecumseh Sherman was raised by neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing, a prominent Whig party member who became United States Senator for Ohio and First Secretary of the United States. Interior of the United States. As an orphan, Sherman had a special admiration for founding father Roger Sherman as a child.

Sherman's family is part of the group formed by the politically influential Baldwin, Hoar &Sherman families. One of his older brothers, Charles Taylor Sherman, becomes a federal judge, and one of his younger brothers, John Sherman, becomes a United States Senator and United States Cabinet Secretary. Another of his younger brothers, Hoyt Sherman, becomes a wealthy banker. Two of his adopted brothers also served as major generals in the Union Army during the Civil War:Hugh Boyle Ewing, a future ambassador and writer, and Thomas Ewing, Jr., who later took on the task of 'defense attorney for certain conspirators responsible for the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Sherman's given names

The unusual first name given to Sherman has always attracted attention. Sherman himself credits his middle name to the fact that his father "got a whim for the great chief of the Shawnees, Tecumseh." Since 1932, several biographers have written that in his early childhood, Sherman was simply named Tecumseh. According to them, Sherman did not acquire the first name William until he was nine or ten years old, after entering the Ewing household. His adoptive mother, Maria Ewing, of Irish descent, is a pious Catholic, and would have had Sherman baptized by a Dominican priest, who would have given him the first name of William because the event would have taken place on the day of Saint William - possibly June 25, the feast day of Saint William of Montevergine.

This version is contradicted by Sherman who states in his memoirs that his father called him "William Tecumseh". There is also evidence that Sherman was baptized by a Presbyterian minister as a child and was then given the first name William. As an adult, Sherman signs all his correspondence, including those addressed to his wife, as "W.T. Sherman", but his friends and family call him "Cump".

Senator Ewing manages to get Sherman, then sixteen years old, admitted as a cadet at West Point Military Academy. He became the roommate and friend of another future Civil War general, George H. Thomas. Fellow cadet William Rosecrans later described Sherman at West Point as "one of the brightest and best-loved comrades" and "a bright-eyed, red-haired comrade, who was always disposed to a playfulness of some kind." Of his time at West Point, Sherman simply writes in Memoirs:

“At the academy, I was not considered a good soldier, because at no time was I selected for any responsibility, and I remained a simple soldier throughout the four years. Then as now, to dress and act neatly, to abide strictly by the rules, were the qualifications for a responsibility, and I suppose I was considered not to excel in any of them. In my studies, I always had an honorable reputation with my teachers, and I was generally ranked among the best, especially in drawing, chemistry, mathematics, physics and philosophy. My average negative points, per year, were around one hundred and fifty, which brought my final ranking from fourth to sixth.”

Upon graduation in 1840, Sherman entered the army as a second lieutenant of the 3rd U.S. Artillery and fought in the Second Seminole War in Florida. He was later stationed in Georgia and South Carolina. As the adopted son of an influential Charleston Whig politician, the popular Lt. Sherman thrives in the high society of the Old South.

While many of his comrades fought in the Mexican-American War, Sherman held administrative positions in the conquered territory of California. Accompanied by his comrade, Lieutenant Edward Ord, he reached the town of Yerba Buena two days before it was renamed "San Francisco", on January 17, 1847.

In 1848, Sherman accompanied the military governor of California, Colonel Richard Barnes Mason, on his inspection tour which officially confirmed that gold had indeed been discovered in the region, thus starting the California gold rush. . Sherman and Edward Ord help survey subdivisions of the city that later becomes Sacramento.

In 1850 Sherman earned his captain's commission for "meritorious service", but the lack of a combat duty assignment discouraged him and no doubt contributed to his decision to resign from the army. During the Civil War, Sherman was thus one of the few high-ranking officers not to have fought in Mexico.

Family life

In 1850 Sherman married Eleanor Boyle Ewing, the daughter of the first Home Secretary, Thomas Ewing. The ceremony takes place in Washington, and President Zachary Taylor and many influential politicians attend.

Like her mother, Ellen Ewing Sherman is a devout Catholic:Sherman's eight children are thus brought up in the precepts of this religion. Although he was baptized twice as a child, Sherman did not join any religious organization during his adult life. In 1878, his son Thomas Ewing Sherman began his novitiate and joined the Society of Jesus. According to him, his father attended the Catholic Church until the outbreak of the Civil War, but not thereafter.

In 1874, Sherman having become famous, their eldest daughter, Marie Ewing Sherman, made a remarkable marriage with Thomas W. Fitch, an officer of the US Navy. President Ulysses S. Grant attends and she receives a generous gift from the Khedive of Egypt. Another daughter of Sherman, Eleanor, married Alexander Montgomery Thackara, the marriage was celebrated at the Shermans' home in Washington, May 5, 1880.

Business career

In 1853, Sherman resigned as captain, and became president of the San Francisco branch of a Saint Louis bank. His return to San Francisco comes during a troubled period in the history of the American West. He survived two shipwrecks, and crossed the Golden Gate on a piece of the frame of the schooner which was to transport him. Sherman's asthma worsens due to stress from the Californian city's frantic financial climate, which also causes him trouble sleeping. Later, recalling the days of mad land speculation in San Francisco, Sherman wrote, "I can handle a hundred thousand men in a battle, and take The City of the Sun, but I'm afraid to have to deal with a piece of land in the San Francisco swamp. In 1856, during the San Francisco Vigilance Movement, he served briefly as a major general in the California militia.

Sherman's bank in San Francisco closed in May 1857, and he was transferred to New York. When the parent company failed during the bank panic of 1857, he turned to the practice of law in Leavenworth, Kansas, without much success.

Director of military academy

In 1859, Sherman accepted the directorship of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning &Military Academy, in Pineville, Louisiana. This position was offered to him by Major Don Carlos Buell and General G. Mason Graham. He proved to be an effective and valued leader at this establishment, which later became Louisiana State University (LSU). Joseph Pannell Taylor, the brother of the late President Zachary Taylor, says that "if you had searched the whole army, from end to end, you would not have found a man more admirably suited for this position in all its aspects, than was Sherman".

Upon learning of South Carolina's secession, Sherman observed to his friend Professor David French Boyd, an enthusiastic secessionist from Virginia:

Cannons used by the South at the start of the War of Secession, in front of the Louisiana State University Military Science Building.

“You southerners don't know what you're doing. This country is going to be covered in blood and only God knows how it will end. This is pure madness, a crime against civilization! You speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You are also wrong about the people of the North. They are a peaceful people, but a fiery people and they too will fight. They will not allow this country to be destroyed without making an immense effort to save it… Moreover, where are the men and the machines of war which you will oppose to them? The North can make a steam engine, a locomotive, or a railroad car, while you can barely make a yard of cloth or a pair of shoes. You throw yourself into a war against one of the most powerful, mechanically resourceful, and determined peoples on Earth - right there, right on your doorstep. You are doomed. It is only in your mind and determination that you are ready for war. In everything else you're utterly bereft, with a bad cause to begin with. At first you will fight back, but as your limited resources begin to run out, cut off from European markets as you will be, your cause will begin to decline. If your people would stop for a moment to think, they would see that in the end you will certainly fail. »

In January 1861, just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Sherman was ordered to receive arms from the United States arsenal in Baton Rouge, for the benefit of the Louisiana state militia. Instead of acquiescing, he resigned as director and returned to the North, declaring to the governor of Louisiana:"For nothing in the world will I do or even have a hostile thought […] vis-à-vis […] the United States. »

After the war, General Sherman donated two cannons to the establishment. These guns were captured from Confederate forces and had been used early in the war to fire at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. They are still on display in front of the LSU Military Science Building.

St Louis Interlude

Immediately after leaving Louisiana, Sherman travels to Washington, probably in hopes of obtaining a post in the army, and meets Abraham Lincoln at the White House the week of his inauguration. Sherman tells him of his concern about the North's state of unpreparedness for the coming war, but Lincoln remains oblivious to his speech.

Sherman was then president of the St. Louis Railroad, a streetcar company, a position he held for only a few months. He therefore lives in a border state, Missouri, when the secessionist crisis reaches its peak. While trying to keep himself out of controversy, he observes the efforts of Congressman Frank Blair, who would serve under him in the war, to keep Missouri in the Union. . At the beginning of April, he refused an offer from the Lincoln administration to take a position in the War Department which would undoubtedly have made him Assistant Secretary of War. After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Sherman hesitates to return to service in the army. He ridicules Lincoln's call for the recruitment of 75,000 volunteers for a period of three months, in order to overcome the secession, declaring:"Look! You might as well try to put out a burning house with a water gun. In May, however, he offered his services to the regular army, and his brother Senator John Sherman and other acquaintances maneuvered to obtain a commission for him. On June 3, he wrote:“I still think it will be a long war – very long – longer than any politician envisages. He finally receives a telegram summoning him to Washington for June 7.

Service during the Civil War

First military commission

On May 14, 1861, Sherman accepted a colonel's commission in the 13th United States Infantry. He was one of the few Union officers to distinguish himself at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, where he was slightly wounded by bullets in the knee and shoulder. The disastrous Union defeat causes Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and the potential of his volunteer troops. However, President Lincoln appointed him Brigadier-General of the Volunteers on May 17, 1861, which theoretically made him the superior of Ulysses Simpson Grant, his future commander. He was assigned to the Cumberland Army in Louisville, Kentucky, under Robert Anderson, whom he succeeded in the fall. Sherman, however, considers his appointment to be a violation of Lincoln's promise not to give him such a senior position.

Nervous breakdown and Shiloh

Having taken over from Anderson in Louisville, Sherman thus received responsibility for a frontier state, Kentucky, in which Confederate troops held Columbus and Bowling Green and were present near the Cumberland Gap pass. He became extremely pessimistic about the prospects of his command, often complained to Washington about shortages, and provided inflated estimates of rebel forces. After Secretary of War Simon Cameron's visit to Louisville in October, press articles very critical of him appeared. In early November, Sherman insisted on being relieved. He was quickly replaced by Don Carlos Buell, and transferred to Saint-Louis, Missouri. In December, he was laid off by Major General Henry W. Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri, who considered him unfit for service. Sherman travels to Lancaster, Ohio, to recuperate. Some historians interpret Sherman's behavior at this time as a nervous breakdown. Back home, his wife Ellen wrote to his brother Senator John Sherman, seeking advice and complaining of "that sickly melancholy to which your family is subject." Sherman himself later wrote that the worries of command "broke him," and he admitted to contemplating suicide. His problems were further compounded when the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper described him as "mad".

Battle of Fort Donelson by Kurz and Allison (1887).

By mid-December, Sherman had recovered sufficiently to return to service under Henry Wager Halleck, commander of the Department of Missouri. Sherman's first assignments were in junior command:the first was in an instruction barracks near St. Louis, then he was given command of the Cairo Military District. Operating from Paducah, it provided logistical support for Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant's operations to take Fort Donelson. Grant, who was the previous commander of this district, had just won a major victory at Fort Henry and was given command of the District of West Tennessee. Although Sherman was technically the senior officer at the time, he wrote to Grant:"I am worried for you, for I know the great facilities which [the Confederates] have in regrouping by means of rivers or railroads, but [I have] faith in you - I am at your command. »

After Fort Donelson was taken by Grant, Sherman obtained service under his orders when he was assigned, on March 1, 1862, to the Army of Tennessee as commander of the 5th Division. His first major test under Grant was the Battle of Shiloh. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6, 1862 took most Union generals by surprise. Sherman in particular disregarded intelligence provided by militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston was about to leave his base in Corinth. He takes no precautions except to reinforce his men on duty, refusing to have trenches and abatis set up, or to send reconnaissance patrols. In Shiloh, he probably wants to avoid appearing overly worried in order to escape the criticism he faced in Kentucky. He wrote to his wife that if he took more precautions, “they would still call me crazy. »

Despite his unpreparedness for the Confederate attack, Sherman managed to rally his troops and led an orderly retreat, which saved the Union forces from a rout. Finding Grant at the end of the day sitting under an oak tree, smoking a cigar in the dark, he experienced "the wise and sudden instinct not to talk about retirement". Instead, in what will become one of the most famous conversations of the war, Sherman simply says, “Well, we had a hell of a day, didn't we? ". After a puff of his cigar, Grant replies calmly, “Yes. Still, we kick their asses tomorrow. Sherman actively participated in the success of the Union counterattack on April 7, 1862. He was wounded twice – in the hand and in the shoulder – and three horses collapsed under him, felled by enemy bullets . His action was praised by Grant and Halleck, and after the battle he was promoted major-general of volunteers on May 1, 1862.

In late April, a Union force of 100,000 fighters slowly advanced against Corinth, under Halleck's command with Grant relegated to second. Sherman leads the division on the extreme right wing, under the command of George H. Thomas. Shortly after Union forces began to occupy Corinth on May 30, Sherman persuaded Grant not to give up his command, despite the serious difficulties he was having with General Halleck. Sherman gives Grant the example of his own life:“before the Battle of Shiloh, I was called crazy by a newspaper, but this simple battle gave me new life and now I am in heaven. He told Grant that, if he remained in the army, "some happy accident will bring you back to favor and to your rightful place." In July, Grant's situation improved when Halleck moved east to become general-in-chief, and Sherman became military governor of occupied Memphis, Tennessee.

Vicksburg and Chattanooga

The career of the two officers therefore follows an ascending phase. In Sherman's case, that's in part because he forged a close personal bond with Grant during the two years they served together in the West. However, at one point during Vicksburg's long and complicated campaign, a newspaper complained that "the army is bogged down, under the direction of a drunkard [Grant], whose personal adviser [Sherman ] is a crackpot”.

Sherman's military career between 1862 and 1863 is mixed. In December 1862, the forces under his command were sharply repulsed at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Soon after, his XV Corps had to come under the orders of Major General John A. McClernand to participate in the attack on the Arkansas Post, generally considered a diversion decided by the politicians, to take Vicksburg. Prior to the Vicksburg campaign in the spring of 1863, Sherman expressed serious reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy, but he faithfully carried out his orders. Following the surrender of Vicksburg, now under the control of Union forces commanded by Grant, on July 4, 1863, Sherman was elevated to the rank of regular army brigadier general, in addition to his rank of major general of the volunteers. Sherman's family travels from Ohio to visit his camp near Vicksburg. This visit ends in the death, due to typhoid fever, of their nine-year-old son, Willie, nicknamed “the little sergeant”.

Subsequently, command in the west passed to Grant (Military Division of Mississippi), and Sherman succeeded him as head of the Army of Tennessee. During the Battle of Chattanooga in November, Sherman quickly took his assigned target, the hill of Billy Goat Hill at the northern end of Missionary Ridge, only to find that it was in fact not doing at all part of the ridge, but is instead a distinct spur, separated from the main ridge by a boulder-strewn ravine. When he attempted to attack the main ridge at Tunnel Hill, his troops were repeatedly repulsed by Patrick Cleburne's heavy division, the best unit in Braxton Bragg's army. Sherman's attempts were overshadowed by the successful assault by George Henry Thomas' army on the center of the Confederate line, a move originally launched as a diversion. Subsequently, Sherman led a column to relieve Union forces under Ambrose Burnside, who were thought to be in bad shape at Knoxville, and in February 1864 led an expedition to Meridian, Mississippi, to sow confusion within the Confederate infrastructure.

Georgia

Sherman appreciates Grant's friendship and trust. When Lincoln called on Grant in the east in the spring of 1864 to take command of the Union armies there, Grant appointed Sherman to succeed him as head of the Mississippi Army Division, which included command of the forces of the western theater of war. Grant now commanding all of the Union armies, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy for ending the war, concluding, "If you can beat Lee and I walk the Atlantic, I think old Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to go and see our little guys.”

Sherman proceeds to the invasion of Georgia with three armies:the Army of Cumberland, strong of 60,000 men and commanded by George Henry Thomas, the Army of Tennessee which then has 25,000 men under the command of James B. McPherson , and the Army of Ohio, whose 13,000 men were led by John M. Schofield49. It was a long campaign of movement in mountainous terrain against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, with only one disastrous direct assault at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. In July, the cautious Johnston was replaced by the reckless John Bell Hood, who challenged Sherman to direct confrontations in the open, where Sherman was to his advantage. It was then, in August, that Sherman “learned [that he had] been made a major general in the regular army, which was unexpected and unwanted before Atlanta was taken.”

Sherman's campaign to capture Atlanta ended victoriously on September 2, 1864. After demanding the departure of all civilians from the city, he ordered the burning of all government and military buildings in the city, but many private homes and businesses were also burned. The capture of Atlanta made Sherman's name popular in the North, and contributed to Lincoln's victory in the November 1864 presidential election. Lincoln's electoral defeat to the Democratic candidate and former army commander of the Union, George B. McClellan, however, seemed probable during the summer. Such an event would have led to the victory of the Confederates, because the Democratic Party at that time called for peace negotiations based on the attainment of independence from the Confederacy. For these reasons, Sherman's capture of Atlanta is arguably his most important contribution to the Union cause.

After Atlanta, Sherman sets out to march due south, declaring that he "will make Georgia scream". Sherman initially overlooks John Bell Hood's army moving into Tennessee, but he must quickly send troops to counter it.

Sherman marched with 62,000 men on the port of Savannah, plundering supplies and causing, by his own estimates, more than $100 million in damage. Sherman calls this tactic hard war, which is known today as total war. At the end of this campaign, known as Sherman's March to the Sea, his troops captured Savannah on December 22, 1864. Sherman then telegraphed Lincoln, giving him the city as a Christmas present.

Sherman's success in Georgia receives extensive media coverage in the North, as Grant appears to be making little progress in his fight against Confederate General Robert Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A bill is introduced in Congress to promote Sherman to the same rank as Grant, with the likely goal of having him replace Grant as commander of the Union armies. Sherman wrote to his brother, Senator John Sherman, and to General Grant, strongly rejecting such a promotion. According to a chronicle from that time, it was around this time that Sherman made his memorable declaration of loyalty to Grant:

“It is reported that a distinguished civilian, who visited him in Savannah, desiring to know his true opinion of General Grant, began to speak of him in disparagement. 'It cannot be; It can't be, Sherman answered me, in his quick and nervous way, 'General Grant is a great general. I know him well. He was by my side when I was crazy and I was by his side when he was drunk, and now, sir, we're side by side forever. »

While in Savannah, Sherman learns from the newspapers that his son Charles Celestine has died while walking to the sea; the general has never seen his child.

Carolinas final campaign

In the spring of 1865, Grant ordered Sherman to embark his army on steamboats to join him in Virginia and help him confront Lee. But Sherman persuades Grant to let him march north through the Carolinas, destroying any strategic and logistical objective he encounters, as he had done in Georgia. He particularly wants to hit South Carolina, the first state to secede, because of the impact it would have on southern morale. His army thus moved north through South Carolina, meeting light resistance from the troops of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Apprenant que les hommes de Sherman avancent sur des chemins de rondins de bois à travers les marais de la rivière Salkehatchie à la vitesse d’une vingtaine de kilomètres par jour, Johnston « se dit qu’il n’y a pas eu d’armée comme celle-ci depuis l’époque de Jules César. »

Sherman capture la capitale de l’État de la Caroline du Sud, Columbia, le 17 février 1865. Des incendies éclatent en ville pendant la nuit, et le lendemain matin, la majeure partie du centre-ville est détruite. L’incendie de Colombia est depuis un sujet de polémique, et les interprétations sont diverses :les feux auraient pu être accidentels, des actes délibérés de vengeance, ou allumés par les confédérés se retirant de la ville. Les guides amérindiens locaux, du groupe ethnique Lumbees, aident l’armée de Sherman à traverser la Lumber River et le centre de la Caroline du Nord sous des pluies torrentielles. Selon Sherman, la difficile traversée de la rivière Lumber, des marais, des pocosins et des ruisseaux du comté de Robeson « fut la plus maudite marche [qu’il ait] jamais vue ». Par la suite, ses troupes n’infligent que des dommages mineurs aux infrastructures civiles de Caroline du Nord, qui est considérée par ses hommes comme un État confédéré réticent, car il a été l’un des derniers à rejoindre la Confédération. Fin mars, Sherman quitte brièvement ses troupes et se rend à City Point, en Virginie, pour s’entretenir avec Grant. Lincoln parvient également à se rendre à City Point au même moment, permettant ainsi la seule réunion tripartite, Lincoln, Grant et Sherman, de toute la guerre.

Après la victoire de Sherman sur les troupes de Johnston à la bataille de Bentonville, la reddition de Lee à Grant à l’Appomattox Court House, et l’assassinat d’Abraham Lincoln, Sherman rencontre Johnston à Bennett Place, dans la ville de Durham, en Caroline du Nord, pour négocier une reddition confédérée. Sur l’insistance de Johnston et du président confédéré Jefferson Davis, Sherman offre des termes de reddition généreux qui prennent en compte les aspects politiques et militaires. Sherman pense que son offre est conforme à la vision exprimée par Lincoln lors de la réunion de City Point, mais il n’a reçu aucune autorité pour négocier au nom des États-Unis, ni de la part de Grant, ni de celle du président nouvellement installé, Andrew Johnson, ni même du Cabinet. Le gouvernement à Washington refuse d’honorer les termes de la reddition, causant une inimitié durable entre Sherman et le secrétaire à la guerre, Edwin M. Stanton. La confusion sur cette question dure jusqu’au 26 avril 1865, quand Johnston, ignorant les directives du président Davis, donne son accord sur les termes purement militaires et se rend formellement avec son armée et toutes les forces confédérées dans les Carolines, la Géorgie et la Floride62. Sherman et ses troupes défilent à Washington le 24 mai 1865, pour le Grand Review of the Armies et sont ensuite congédiées. Après être devenu le second plus important général de l’armée de l’Union, il ferme ainsi la boucle dans la ville même où il commence son service comme colonel d’un régiment d’infanterie inexistant.

Esclavage et émancipation

Bien qu’il finisse par désapprouver l’esclavage, Sherman n’était pas un abolitionniste avant la guerre. Comme beaucoup, dans le contexte de son époque, il ne croit pas à « l’égalité du nègre ». Ses campagnes militaires de 1864 et de 1865 permettent de libérer de nombreux esclaves, qui l’accueillent « comme le second Moïse ou comme Aaron » et se joignent à sa marche à travers la Géorgie et les Carolines par dizaines de milliers.

Le sort de ces réfugiés devient un problème militaire et politique pressant. Quelques abolitionnistes accusent Sherman d’en faire trop peu pour soulager les conditions de vie précaires des esclaves libérés Pour règler ce problème, le 12 janvier 1865, Sherman rencontre à Savannah le secrétaire à la guerre Stanton et des leaders noirs locaux. Après le départ de Sherman, Garrison Frazier, un ministre baptiste, déclare en réponse à une question au sujet des sentiments de la communauté noire :

« Nous considérions le général Sherman, avant son arrivée, comme un homme, dans la providence de Dieu, spécialement créé pour accomplir cette œuvre et nous avons unanimement ressenti envers lui une ineffable gratitude, le considérant comme un homme qui doit être honoré pour le fidèle accomplissement de son devoir. Certains d’entre nous firent appel à lui dès son arrivée et il est probable qu’il n’aurait pas répondu au [Secrétaire Stanton], avec plus de courtoisie que lorsqu’il nous rencontra. Sa conduite et son comportement envers nous le caractérisent comme un ami et un gentleman. »

Quatre jours plus tard, Sherman publie les Special Field Orders, No. 15. Ces consignes ordonnent l’établissement de 40 000 esclaves libérés et de réfugiés noirs sur les terres de Blancs expropriés, en Caroline du Sud, Géorgie et Floride. Sherman nomme, pour mettre en œuvre ce plan, le brigadier-général Rufus Saxton, un abolitionniste du Massachusetts, qui avait précédemment dirigé le recrutement de soldats noirs. Ces consignes, qui sont à la base de la revendication selon laquelle le gouvernement de l’Union a promis aux esclaves libérés « 40 acres et une mule », sont révoquées plus tard dans l’année par le président Andrew Johnson.

Bien que ce contexte soit souvent négligé, et la citation généralement tronquée, l’une des déclarations les plus célèbres de Sherman à propos de son point de vue sur la « guerre-dure » vient en partie des attitudes raciales résumées précédemment. Dans ses mémoires, Sherman remarque les pressions politiques entre 1864 et 1865 afin d’encourager la fuite des esclaves, en partie pour éviter la possibilité que « les esclaves aptes soient appelés à servir au sein de l’armée des rebelles ». Sherman pense qu’encourager une telle politique retarderait la « fin victorieuse » de la guerre et la « libération de tous les esclave ». Il résume de façon éclatante sa philosophie de la « guerre-dure », et ajoute, en effet, qu’il ne veut pas vraiment l’aide d’esclaves libérés pour soumettre le Sud :

« Mon objectif était alors de battre les rebelles, de rappeler leur fierté à plus d’humilité, de les poursuivre dans leurs derniers retranchements, et de leur inspirer peur et effroi. La crainte de l’Éternel est le commencement de la sagesse. Je ne voulais pas qu’ils nous jettent au visage, ce que le général Hood avait fait à Atlanta, que nous avions dû faire appel à leurs esclaves pour nous aider à les vaincre. Mais, s’agissant de la bonté envers la race …, je tiens à affirmer qu’aucune armée n’a jamais plus fait pour cette race que celle que j’ai commandée à Savannah. »

Stratégies

Les résultats de Sherman en tant que tacticien sont mitigés et son héritage militaire repose principalement sur son sens de la logistique et sur sa réussite en tant que stratège. Le théoricien et historien militaire britannique Liddell Hart range Sherman dans les stratèges les plus importants dans les annales de l’art de la guerre, avec Scipion l’Africain, Bélisaire, Napoléon Ier, Thomas Edward Lawrence et Erwin Rommel. Liddell Hart attribue à Sherman la maîtrise de la guerre de mouvement (également connue sous le nom « d’approche indirecte »), comme il l’a démontré par sa série de mouvements tournants contre Johnston lors de la campagne d’Atlanta. Liddell Hart note également que l’étude des campagnes de Sherman a contribué pour une grande part à sa propre « théorie de stratégie et de tactique dans la guerre mécanisée », qui influence à son tour la doctrine de Blitzkrieg de Heinz Guderian et l’utilisation par Rommel des chars de combat durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Un autre lecteur attentif des écrits de Liddell à propos de Sherman fut George S. Patton, qui « passa de longues vacances à étudier les campagnes de Sherman en Géorgie et dans les Carolines, grâce au livre [de Liddell] » et plus tard « mit au point ses propres plans, à la manière d’un ’super-Sherman’ ».

La plus importante contribution de Sherman à l’art de la guerre, la stratégie de la guerre totale - approuvée par le général Grant et le président Lincoln - fut le thème de nombreuses polémiques. Sherman lui-même minimisa son rôle dans la conduite de la guerre totale, indiquant souvent qu’il exécutait simplement les ordres du mieux qu’il pouvait afin d’accomplir sa part du maître plan de Grant pour mettre un terme à la guerre.

Guerre totale

Comme Grant, Sherman est convaincu que les capacités stratégiques, économiques, et psychologiques de la Confédération doivent être définitivement détruites, pour obtenir la fin de la guerre. Par conséquent, il pense que le Nord doit conduire sa campagne comme une guerre de conquête, et employer la politique de la terre brûlée pour briser la colonne vertébrale de la rébellion, tactique qu’il nomme hard war (« guerre-dure »).

L’avance de Sherman à travers la Géorgie et la Caroline du Sud se caractérise par d’importantes destructions des approvisionnements et des infrastructures civiles. Bien que le pillage soit officiellement interdit, les historiens sont en désaccord sur la façon dont cette réglementation était appliquée. La rapidité et l’efficacité des destructions causées par l’armée de Sherman sont remarquables. La technique développée pour plier les rails de chemin de fer autour des arbres ou des poteaux télégraphiques, qui laisse sur place ce que l’on nomme à l’époque des cravates de Sherman, rend les réparations très difficiles. Les accusations de crimes de guerre lors de la marche vers la mer et les allégations selon lesquelles des civils auraient été pris pour cible font de Sherman une figure aujourd’hui controversée, en particulier dans le sud des États-Unis.

Les dégâts que cause Sherman se concentrent principalement sur les grandes propriétés terriennes. Bien que des données précises n’existent pas, il semble que les pertes civiles furent minimes. Incendier les provisions, détruire les infrastructures et saper le moral du Sud sont les buts avoués de Sherman. Ces pratiques sont connues dans le Sud et suscitent d’abondants commentaires. Le major Henry Hitchcock qui est né en Alabama mais fait partie de l’état-major de Sherman, déclare que « c’est une chose terrible que de détruire la subsistance de milliers de gens », mais que si la politique de la terre brûlée permet « de paralyser leurs maris et leurs pères qui se battent … c’est finalement une action de miséricorde. »

La gravité des actes de destruction commis par les troupes de l’Union est sensiblement plus importante en Caroline du Sud qu’en Géorgie ou en Caroline du Nord, ce qui semble être une conséquence de l’animosité des soldats et des officiers de l’Union à l’encontre de cet État qu’ils considèrent comme le « poste de pilotage de la sécession ». Une des accusations les plus sérieuses contre Sherman est qu’il a permis à ses troupes de brûler la ville de Columbia. Sherman lui-même déclare :« si j’avais décidé de faire incendier Columbia, je l’aurais brûlée sans plus de remords que s’il s’était agi d’une colonie de chiens de prairie; mais je ne l’ai pas fait […] » Cependant, le 5 avril 1865, Sherman écrit à son beau-père :« Je pense que vous seriez satisfait de la manière dont je dispose de Charleston, ainsi que de l’incendie de Columbia. » L’historien James M. McPherson conclut :

« L’étude la plus complète et la plus objective de cette controverse accuse toutes les parties dans des proportions variables, y compris les autorités de la Confédération pour le désordre qui caractérisa l’évacuation de Columbia, laissant des milliers de balles de coton dans les rues (dont certaines d’entre elles en feu) et d’énormes quantités d’alcool […] Sherman n’a pas délibérément brûlé Columbia, la plupart des soldats de l’Union, y compris le général, ont tenté toute la nuit d’éteindre les incendie. »

Sherman et ses subordonnés (en particulier John A. Logan) ont pris des mesures afin de protéger Raleigh, en Caroline du Nord, de tout acte de vengeance après l’assassinat du président Lincoln.

Évaluation moderne

Après la chute d’Atlanta en 1864, Sherman ordonne l’évacuation de la ville. Le conseil municipal l’exhorte de rapporter cet ordre, au motif que cela causerait de grandes difficultés aux femmes, aux enfants, aux personnes âgées, et à d’autres qui ne portent aucune responsabilité dans la conduite de la guerre. Sherman envoie alors une réponse dans laquelle il cherche à exprimer sa conviction qu’une paix durable ne sera possible que si l’Union est rétablie, et qu’il est donc prêt à faire tout ce qu’il peut pour réprimer la rébellion :

« Vous ne pouvez qualifier la guerre en des termes plus sévères que je ne le ferais. La guerre est cruauté, et vous ne pouvez l’adoucir; et ceux qui ont amené la guerre à notre pays méritent toutes les imprécations et les malédictions qu’un peuple puisse verser. Je sais que je ne suis pas responsable de cette guerre, et je sais que je vais faire plus de sacrifices jour après jour qu’aucun d’entre vous pour obtenir la paix. Mais vous ne pouvez avoir la paix et un pays divisé. Si les États-Unis acceptent maintenant une division, ça ne s’arrêtera pas, mais ira jusqu’à ce que nous partagions le sort du Mexique, qui est perpétuellement en guerre. […] Je veux la paix, et pense qu’elle ne peut être atteinte que par l’union et la guerre, et je conduirai toujours cette guerre en vue d’un succès parfait et rapide. Mais, mes chers messieurs, quand la paix viendra, vous pourrez faire appel à moi en toute chose. Alors je partagerai avec vous mon dernier biscuit, et veillerai avec vigilance sur vos foyers et vos familles contre tous les dangers d’où qu’ils viennent. »

Le critique littéraire Edmund Wilson trouva dans les Memoirs de Sherman une description fascinante et inquiétante d’un « appétit pour la guerre » qui « croît alors qu’il se nourrit du Sud ». L’ancien secrétaire à la Défense des États-Unis Robert McNamara fait une référence équivoque à l’assertion « la guerre est cruauté, et vous ne pouvez l’adoucir » dans son livre Wilson’s Ghost et lors de son interview pour le film The Fog of War.

L’historien sud-africain Hermann Giliomee compare la stratégie de la terre brûlée de Sherman aux actions de l’armée britannique pendant la Seconde Guerre des Boers (1899-1902), une autre guerre dans laquelle les civils sont pris pour cible en raison de leur rôle central dans le soutien d’une résistance armée. Il écrit qu’il « semble que Sherman ait trouvé un meilleur équilibre que les commandants britanniques, entre sévérité et retenue, prenant des mesures proportionnelles à ses besoins légitimes ». L’admiration de chercheurs tels que Victor Davis Hanson, Basil Liddell Hart, Lloyd Lewis et John F. Marszalek pour le général Sherman doit beaucoup à ce qu’ils considèrent comme une approche moderne des exigences d’un conflit armé, qui se doit d’être à la fois efficace et fondé sur des principes.

Carrière après-guerre

En mai 1865, après la capitulation des plus importantes armées confédérées, Sherman écrit dans une lettre personnelle :

« J’avoue, sans honte, que je suis malade et fatigué de combattre; la gloire n’est que balivernes; même le plus brillant succès n’est fait que de corps mutilés ou morts, avec l’angoisse et les lamentations des familles me réclamant leurs fils, maris et pères […] il n’y a que ceux qui n’ont jamais entendu un coup de feu, jamais entendu le hurlement et les gémissements des hommes blessés et déchirés […] qui vocifèrent pour plus de sang, plus de vengeance, plus de désolation. »

En juillet 1865, trois mois après la reddition de Robert E. Lee à Appomattox, Sherman est nommé à la tête de la Division militaire du Missouri, qui comprend alors tous les territoires à l’ouest du Mississippi. Son souci principal à ce poste est de protéger la construction et le fonctionnement des chemins de fer des attaques indiennes. Lors de ses campagnes contre les tribus indiennes, Sherman répète la stratégie qui fut la sienne lors de la Guerre de Sécession, cherchant non seulement à vaincre les guerriers ennemis, mais aussi détruire les ressources qui leur permettent de soutenir l’effort de guerre. La politique qu’il met en place comprend un large massacre des bisons d’Amérique du Nord, qui sont alors à la base de l’alimentation des Indiens des Plaines.

L’attitude du gouvernement américain à l’égard des Amérindiens se retrouve dans les propres mots de Sherman, comme le rapporte l’Independent Institute :

« Nous n’allons pas laisser quelques voleurs indiens déguenillés contrôler et stopper la progression des chemins de fer. … Je considère le chemin de fer comme le plus important élément actuellement en développement permettant de faciliter nos intérêts militaires sur la frontier.

Nous devons agir avec une sérieuse détermination contre les Sioux, même jusqu’à leur extermination, hommes, femmes et enfants. [Les Sioux doivent] ressentir la toute-puissance du gouvernement. [Je fais le vœu de rester dans l’Ouest] jusqu’à ce que tous les Indiens aient été tués ou emmenés dans un pays où ils peuvent être surveillés.

Au cours d’un assaut,[...] les soldats ne peuvent s’arrêter pour distinguer entre hommes et femmes, ou même faire une discrimination entre les âges. »

Dans une lettre adressée à Grant en 1867, il se réfère à cette dernière phrase qu’il donnait comme ordre à ses troupes, et l’appelle « la solution finale au problème indien86. » En dépit de sa dureté envers les tribus hostiles, Sherman stigmatise le traitement injuste des Indiens, par les spéculateurs et les agents du gouvernement, au sein des réserves.

Le 25 juillet 1866, le Congrès crée le grade de général de l’Armée pour Grant, et promeut ensuite Sherman à celui de lieutenant-général. Quand Grant devient président en 1869, Sherman est nommé Commanding General of the United States Army. Après la mort de John A. Rawlins, Sherman devient pendant un mois, secrétaire à la guerre. Sa carrière de Commanding General est troublée par des difficultés politiques, et de 1874 à 1876, il déplace son état-major à Saint Louis, dans le Missouri, afin d’échapper à la pression des politiciens de Washington. L’une de ses contributions significatives en tant que chef de l’armée est la fondation de la Command School à Fort Leavenworth, une école de formation des cadres de l’U. S. Army qui se nomme aujourd’hui le Command and General Staff College.

En 1875, Sherman publie ses mémoires, un ouvrage en deux volumes. Selon le critique Edmund Wilson, « Sherman possédait un don pour s’exprimer, comme le dit Mark Twain, un « maître du récit ». [Dans ses mémoires] le compte-rendu vigoureux de ses activités d’avant guerre puis de sa conduite des opérations militaires est varié, dans de justes proportions et comporte un juste degré de vivacité avec des anecdotes et des expériences personnelles. Nous vivons à travers ses campagnes […] en compagnie de Sherman lui-même. Il nous dit ce qu’il pensait et ce qu’il a ressenti, et il ne laisse entendre aucune attitude, ni ne prétend rien ressentir d’autre que ce qu’il a effectivement ressenti. »

Le 19 juin 1879, Sherman fait un discours devant les cadets de l’Académie Militaire du Michigan, au cours duquel il a probablement proféré son célèbre War is Hell (« la guerre c’est l’Enfer »). Le 11 avril 1880, il s’adresse à une foule de plus de 10 000 personnes à Columbus, dans l’Ohio :« Il y a plus d’un garçon aujourd’hui qui ne voit en la guerre que gloire, mais, mes garçons, elle n’est qu’enfer ». En 1945, le président Harry S. Truman déclara :« Sherman avait tort. Je vous le dis, je trouve que la paix, c’est l’Enfer. »

Sherman démissionne de son poste de Commanding General le 1er novembre 1883, et se retire de l’armée le 8 février 1884. Il passe la majeure partie du reste de son existence à New York. Il se consacre au théâtre et à la peinture en amateur, et il est très demandé en tant qu’orateur à des dîners ou des banquets au cours desquels il aime citer Shakespeare92. Sherman est proposé comme candidat républicain à l’élection présidentielle de 1884, mais il refuse aussi énergiquement qu’il est possible, déclarant :« si l’on me propose, je ne ferai pas campagne; si je suis nommé, je n’accepterai pas; si je suis élu, je n’exercerai pas mon mandat. » Le rejet aussi catégorique d’une candidature est aujourd’hui connu aux États-Unis sous le nom de Shermanesque statement (déclaration Shermanesque).

Autobiographie et mémoires

Vers 1868, Sherman rédige un « recueil privé » sur sa vie avant la guerre civile, destiné à ses enfants. Cet ouvrage est connu de nos jours comme son Autobiography, 1828-1861 non publiée. Le manuscrit est conservé par l’Ohio Historical Society. La matière qu’il contient pourrait être éventuellement incorporée dans une forme révisée de ses mémoires.

En 1875, dix ans après sa conclusion, Sherman est le premier général de la Guerre de Sécession à publier des mémoires. Son Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. By Himself (« Mémoires du Général William T. Sherman. Par lui-même »), publié par D. Appleton &Company, se présente sous la forme de deux volumes, commençant en 1846 (ce qui coïncide avec le début de la guerre américano-mexicaine), et s’achevant par un chapitre sur les « leçons militaires de la guerre [civile] ». Cette publication suscite controverses et plaintes. Grant, qui exerce alors le mandat de président des États-Unis, mentionne plus tard que certains lui affirmaient que Sherman le traitait injustement dans son ouvrage. Il déclare pourtant :« Lorsque j’ai achevé la lecture du livre, j’ai constaté que j’en approuvais chaque mot … c’était un livre vrai, un livre honorable, à mettre au crédit de Sherman, juste pour ses compagnons - pour moi-même en particulier - juste comme le livre que j’espérais que Sherman écrivît. »

En 1886, après la parution des mémoires de Grant, Sherman sort une « seconde édition, révisée et corrigée » de ses mémoires chez Appleton. À la nouvelle édition sont ajoutés une seconde préface, un chapitre sur sa vie jusqu’en 1846, un autre sur l’après-guerre (se terminant par sa retraite de l’armée en 1884), plusieurs annexes, portraits, cartes améliorées et un index.

Dans l’ensemble, Sherman refuse de réviser son texte original du fait, écrit-il, que « je décline le qualificatif d’historien, mais assume être un témoin se présentant devant le grand tribunal de l’histoire » et « que tout témoin qui peut être en désaccord avec moi devrait publier un récit véridique de sa propre version des faits ». Cependant, Sherman ajoute des annexes, dans lesquelles il apporte certains points de vue extérieurs.

Par la suite, Sherman change de maison d’édition pour la Charles L. Webster &Co., l’éditeur des mémoires de Grant. Le nouvel éditeur sort une « troisième édition, révisée et corrigée » en 1890. Cette édition est substantiellement identique à la seconde, si ce n’est la probable omission des courtes préfaces de Sherman présentes dans les éditions de 1875 et de 1886.

Après la mort de Sherman en 1891, de nouvelles éditions concurrentes de ses mémoires sont éditées. Son éditeur original, Appleton, révise l’édition originale de 1875, avec deux nouveaux chapitres sur les dernières années de Sherman, ajoutées par le journaliste W. Fletcher Johnson. Entre-temps, Charles L. Webster &Co. publie une « quatrième édition, révisée, corrigée, et complétée » du texte de la seconde édition de Sherman, qui ajoute un nouveau chapitre, préparé sous les auspices de la famille Sherman, et portant sur la vie du général depuis sa retraite jusqu’à sa mort, ainsi qu’un éloge du Secrétaire d’État James Blaine, qui est un parent de l’épouse de Sherman. Cette édition omet les préfaces de Sherman des éditions de 1875 et de 1886.

En 1904 et 1913, le plus jeune fils de Sherman, Philemon Tecumseh Sherman, republie les mémoires chez Appleton, et non pas Charles L. Webster &Co. Celle-ci est intitulée « seconde édition, révisée et corrigée ». Elle contient les deux préfaces de Sherman, son texte de 1886, et les ajouts de celle de 1891. Cette édition très rare des mémoires de Sherman est la version la plus complète.

Il existe de nombreuses éditions modernes des mémoires de Sherman. L’édition la plus propice à des fins d’études est celle de la Library of America de 1990, éditée par Charles Royster. Cette version contient le texte complet de l’édition de Sherman de 1886, ainsi que des annotations, un commentaire sur le texte, et une chronologie détaillée de la vie de Sherman. Il manque cependant à cette édition l’important matériel biographique des éditions de Johnson et Blaine de 1891.

Correspondance publiée

De nombreuses lettres officielles du temps de guerre de Sherman (et d’autres articles) apparaissent dans les Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Certaines de ces lettres sont de nature personnelle, plutôt que se rapportant directement aux activités opérationnelles de l’armée. Il existe également au moins cinq collections éditées de correspondance de Sherman :

Sherman’s Civil War :Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, édités par Brooks D. Simpson et Jean V. Berlin (Chapel Hill :The University of North Carolina Press, 1999) — une large collection de lettres écrites durant la guerre (novembre 1860 à mai 1865).

Sherman at War, édité par Joseph H. Ewing (Dayton, OH :Morningside, 1992) — Près de trente lettres écrites par Sherman durant la guerre à l’attention de son beau-père, Thomas Ewing, et à son beau-frère, Philemon B. Ewing.

Home Letters of General Sherman, édité par M.A. DeWolfe Howe (New York :Charles Scribner’s Son, 1909) — Lettres adressées à sa femme, Ellen Ewing Sherman, de 1837 à 1888.

The Sherman Letters :Correspondence Between General Sherman and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891, édité par Rachel Sherman Thorndike (New York :Charles Scribner’s Son, 1894) — Lettres adressées à son frère, le Sénateur John Sherman, entre 1837 et 1891.

General W.T. Sherman as College President, édité par Walter L. Fleming (Cleveland :The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1912) — Lettres éditées et autres documents écrits par Sherman alors qu’il était le Directeur de la Louisiana Seminary of Learning and Military Academy entre 1859 et 1861.

Death and posterity

Sherman meurt à New York le 14 février 1891. Le 19 février, un service funèbre a lieu à son domicile, suivi par une procession militaire. Le corps de Sherman est ensuite transporté à Saint-Louis, où un autre service a lieu le 21 février, dans une église catholique. Son fils, Thomas Ewing Sherman, prêtre jésuite, officie lors de la messe dite pour son père. Le général Joseph E. Johnston, l’officier de la Confédération qui avait commandé la résistance aux troupes de Sherman, en Géorgie et dans les Carolines, est l’un des porteurs du cercueil lors de la cérémonie à New York. Comme il s’agit d’une froide journée, un ami de Johnston, craignant que celui-ci ne tombe malade, lui conseille de mettre son chapeau. La réponse de Johnston est restée célèbre :« Si j’étais à la place de [Sherman], et lui à la mienne, il ne porterait pas son chapeau. » Johnston attrapa froid et mourut un mois plus tard de pneumonie.

Sherman repose dans le Calvary Cemetery (cimetière du calvaire) de Saint-Louis. Les principaux monuments à sa mémoire comprennent la statue équestre en bronze doré d’Augustus Saint-Gaudens à l’entrée principale de Central Park, à New York, et le monument du mémorial Sherman de Carl-Smith Rohl près du Parc du Président, à Washington.

Parmi les autres hommages posthumes, on peut citer le char de combat M4 Sherman de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et le séquoia géant baptisé « General Sherman », un des arbres les plus imposants au monde.

La marche de Sherman vers la mer a donné lieu à certaines représentations artistiques, comme cette chanson de la période de guerre civile Marching Through Georgia de Henry Clay Work; le poème de Herman Melville The March to the Sea105; le film Sherman’s March de Ross McElwee; et le roman The March d’E. L. Doctorow. Au début du roman Autant en emporte le vent de Margaret Mitchell, publié pour la première fois en 1936, le personnage de fiction Rhett Butler avertit un groupe d’aristocrates sécessionnistes de la folie de la guerre avec le nord en termes très proches de ceux adressés par Sherman à David F. Boyd avant de quitter la Louisiane. L’invasion de la Géorgie par Sherman joue plus tard un rôle central dans l’intrigue du roman. Charles Beaumont dans l’épisode de la Quatrième Dimension, Longue vie, Walter Jameson, fait dire à son personnage principal (un professeur d’histoire) à propos de l’incendie d’Atlanta que les soldats de l’Union l’ont fait à contrecœur à la demande d’un Sherman décrit comme renfrogné et abruti. La représentation de Sherman dans la culture populaire est abondamment discutée tout au long de l’ouvrage Sherman’s March in Myth and Memory (Rowman &Littlefield, 2008) par Edward Caudill et Paul Ashdown.