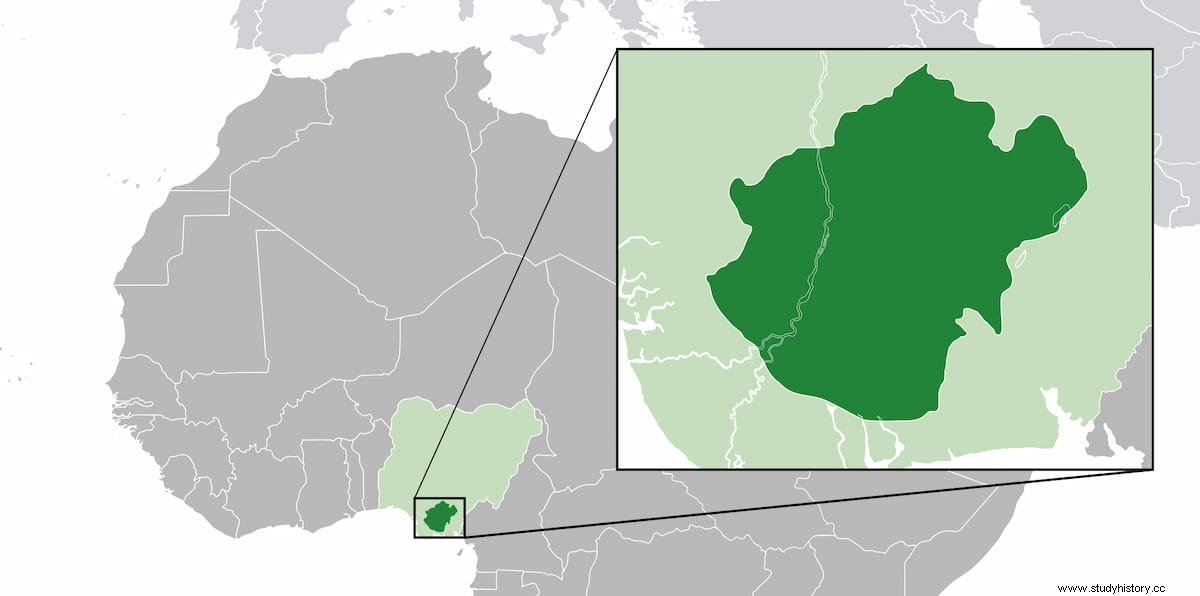

In the 10th century AD the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms united to form England, Abderramán III proclaimed the Caliphate of Córdoba, the Holy Roman Empire was born, the Capetians ascended the French throne and the Viking Leif Eriksson arrived in Newfoundland, where further south the Toltec civilization reached its maximum splendor . At the same time, in Africa, to the south of present-day Nigeria, a strange state appeared that expanded without violence thanks to embassies that preached a redeeming message and because the seminal territory had a sacred, mythical character, as the birthplace of its divine founder. It was the Kingdom of Nri, which lasted no less than a millennium.

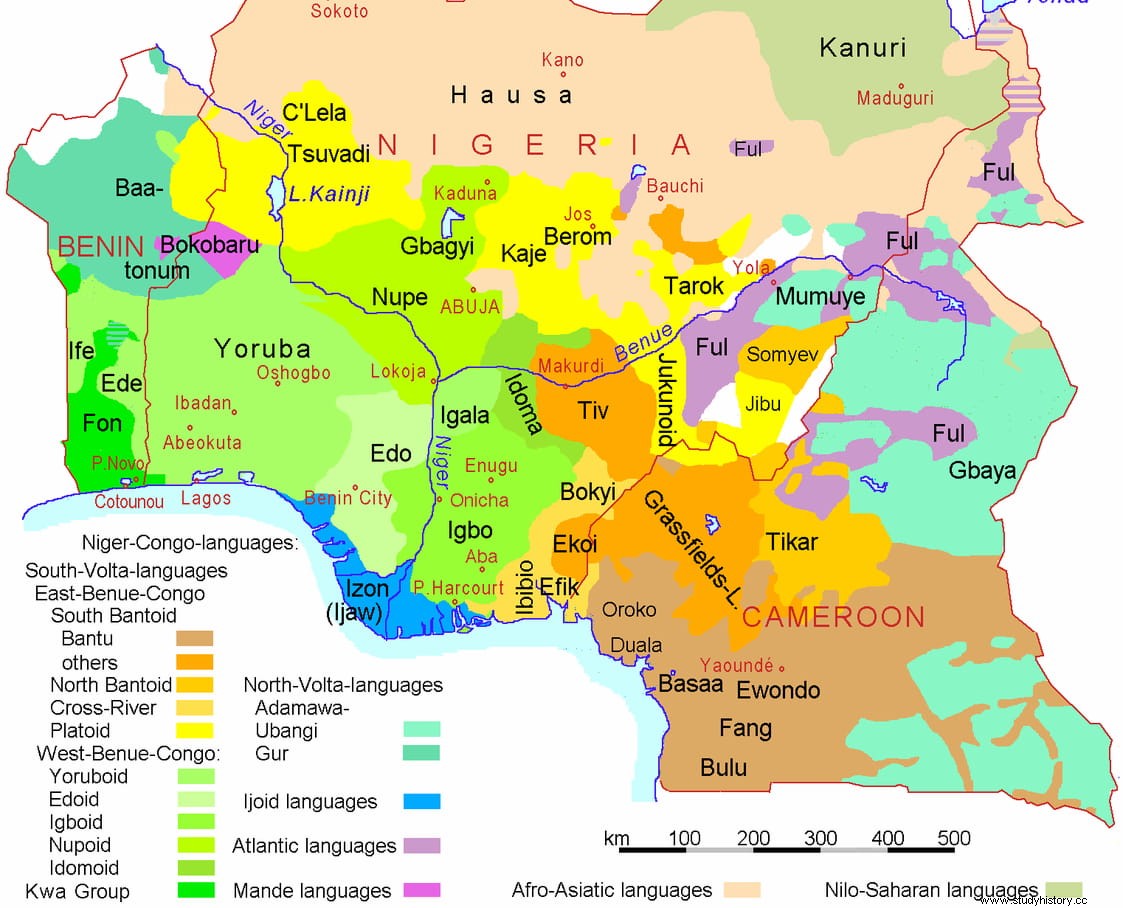

The Kingdom of Nri is considered the highest manifestation of the Igbo, a people that constitutes one of the largest minorities in the multi-ethnic Nigeria but which, in addition, today extends to other neighboring countries such as Cameroon, Ghana and Equatorial Guinea. Its origin is not clear, although the similarity of its language (which has numerous dialects) with those of other groups, such as the Yorubas, Igalas and Idomas, allows us to deduce that they were related in prehistory, five or six thousand years ago. A more poetic version tells that they were originally from Egypt, although today it is considered a legend based on the commercial ties that did exist with the Nile Valley.

In fact, until the 20th century, the Igbo did not form a single group, but were divided into nearly two hundred variants, each one subdivided into thirty peoples; all with common elements obviously, but with enough differences to not have to think of them in a monolithic way. In fact, it is likely that they received influences from other ethnic groups in the Niger region, such as the Nok, or from localities such as Ife and Benin, related to the aforementioned Yoruba. In any case, it seems that their original settlements were at the confluence between the Niger (on its eastern margin) and the Benue, from where they spread.

The spark for that expansion was the Umeuri and Umunri clans, from which came the ruling castes of the Igbo country and adjoining regions. Both considered themselves descendants of a common ancestor named Eri, whom mythology identified as envoy of Chukwu (or Chineke), the supreme creator god of the world, to provide a modern social order for the people. Eri was supposed to be half divine, hence Chukwu constantly protected him, sending the blacksmith Awka to dry out the marshy land where he settled with bellows and charcoal, as well as periodically providing him with a special meal called azu-igwe .

Eri settled in the valley of the Anambra River, in Aguleri, where he married two women. The first was Nneamakụ, who bore him four sons and one daughter:Agulu, Attah, Oba, Menri, and Adamgbo, respectively. They founded cities and towns:the firstborn, the city of Aguleri and its ruling dynasty, Ezeora; the second, the kingdom of Igala; Oba, Benin; and Menri migrated from Aguleri to found the Kingdom of Nri and his dynasty, Umunri. With a second wife, Oboli, Eri had another offspring named Onoja who, according to other versions, would have been the creator of the aforementioned Kingdom of Igala (in the current Nigerian state of Kogi) instead of Attah.

Menri is also known by his foundation name, Nri. When his father passed away, he complained to Chukwu that he interrupted the azu-igwe of maintenance. The god responded by ordering him to sacrifice his first son and daughter and to bury them separately; he obeyed and a few weeks later yams sprouted from the graves. He then repeated the offering with slaves, obtaining the breadfruit tree and the oil palm, thanks to which the clan prospered. The similarity of this story with the biblical story of Jacob meant that, later, when Christianity spread through that part of Africa, Eri was identified as the son of Gaad, in turn the son of the Hebrew patriarch; Jacob's grandson, then.

In any case, the tombs excavated by archaeologists and dated to the 9th century show that there was a settlement in Nri prior to the Eri stage, which covers the year 948 to 1051 AD. Because, myths aside, we know the name of the first eze or ozo (king) of Nri, successor of Eri, and is Ìfikuánim. With him a new period begins, that of the emigrations that culminated in a unification process in 1252 AD, although the dates are relative because they are determined by the coronations, ignoring the phases that existed between them, which could be long because tradition forced to let at least seven years pass.

From this it follows that it was not a hereditary monarchy but by appointment by a priestly caste, that of the ndi , who would interpret through divinatory arts the designation made by the deceased sovereign from beyond. Even the coronation ceremony went in that direction:it was held in the holy city of Aguleri, to which the future eze was to make a pilgrimage. to undergo a symbolic burial and exhumation, before being anointed with white clay as a metaphor for purity. Along the same lines, when he died he was buried with great pomp in a wooden sarcophagus.

Let's keep in mind what we said before:a couple of clans took over the religious hierarchies of Nri and imposed that belief system on the other cities of the Niger Delta that were in their orbit of influence, such as Onitsha, Aboth and Oguth. They had their own political ranks, based on lineages (especially on the western shore of the delta), with the noted obi at the head of each one, but all were subject to the eze of Nri, which was thus the pinnacle of a decentralized kingdom with a marked theocratic character. To be exact, the eze he was a religious head rather than a monarch in itself, and he bore a certain resemblance to the Pope in his election and performance of his office, which meant another element of rapprochement with Christianity.

But the eze He was one step further, having divine consideration. That is why his superiority served as a glue for the different types of political administration that existed and to control an abundant population, using a faith based on inviolable taboos as a tool. Among them was, for example, the ritual death of children born with defects or in an abnormal way (twins, albinos, those whose upper teeth came out earlier or those who came from feet instead of heads), although also, paradoxically, , the rejection of violence, whose possible practitioners could be marginalized in all areas (political, social and economic), with the damage that this would cause them; including entire villages, if that was the case. Again, another point of contact with the Christian religion was seen in this, when this postponement was compared to excommunication.

And it is that The Kingdom of Nri was forged in an almost unusual way in the history of the world:without resorting to conquests. Instead of sending armies against other cities to annex them, what they did was spread their message of peace and harmony through merchants, analogous to the pochtecas Mexicas, who managed to reach a pact based on a ritual oath of loyalty to the ikénga , worship of the homonymous god of power, associated with the right hand, and the eze of Nri as the central authority. One of the ways to consolidate that bond was the celebration of the Igu Aro , a festival that took place every four years in which the obis they came to show their loyalty with a tribute and the eze I answered them with a yam or blessing of fertility for your fields.

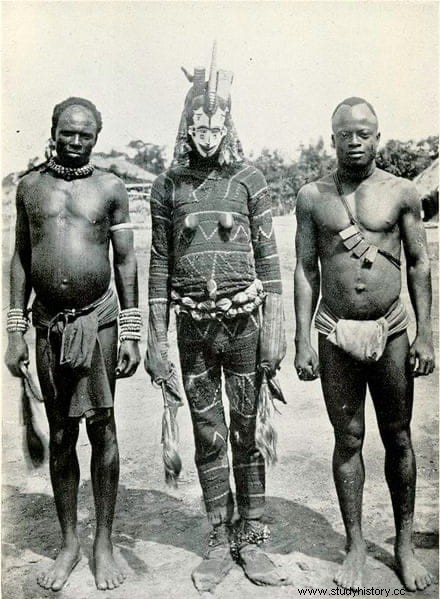

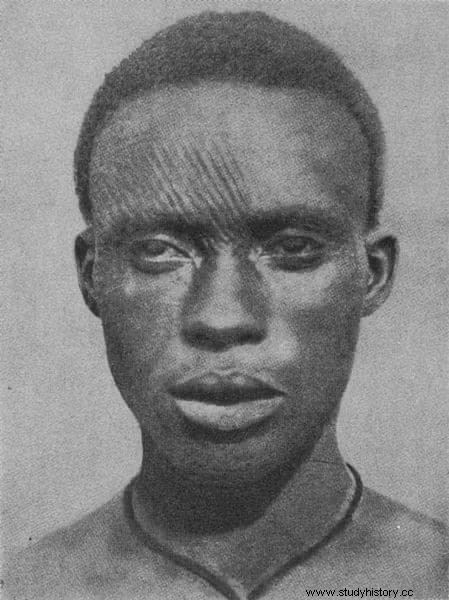

In this way, Nri expanded to the limits of another kingdom, that of Benin (on the west bank of the Niger), in a process that lasted another four centuries, culminating in 1679 AD. During that time, it was a peaceful kingdom ruled in practice by the aforementioned ndi caste. (official priests), since the monarch lived withdrawn from worldly life. Identifiable thanks to the ichi (facial scarifications) worn by its members, the ndi they traveled through the territories of the kingdom, called odinani generically, imparting justice or promoting economic prosperity through rituals. They were also in charge of appointing local representatives, the mbùríchi , nobles who obtained that dignity by purchase.

Consequently, we said, between the 13th and 15th centuries the Kingdom of Nri experienced a boom that was reflected in the economy, based on agriculture, as corresponded to the subsistence mode that the jungle forced. To guide themselves, they had a calendar of twenty-eight days divided into weeks of four and these into months of seven, which yielded years of thirteen months. The work was shared between men and women, the former dealing with yam cultivation and the latter with everything else (cassava, pumpkin, melon...). The land was communal property of each clan and, as is common in Africa, the possession of cattle gave social status.

However, as important as the harvests or even more was the commercial activity, both inside and outside. They had no problem exchanging with other ethnic groups and their routes reached Egypt thanks to the maintenance of roads through collective work. On the other hand, slavery was not part of the Igbo economy, something unusual in these latitudes of the continent and, in fact, slaves who arrived fleeing to Nri and Agukwu were even granted freedom, at least from the tenth eze .

The splendor also occurred in the cultural field. Above all in art, which had a particularly important manifestation in bronze casting, of which there are pieces from at least the 9th century with a generally faunal theme, often elephant heads but also other animals such as snakes, birds, etc. The most important deposits are in Obiuno, Ngo and Ihite, neighborhoods belonging to Igbo-Ukwu, a town located six kilometers from Nri; Objects were also found there that revealed more metallurgical practices (in copper and iron), as well as ceramics, jewelry and even a body buried with traditional ornaments.

The good times, although already in decline, continued until the last quarter of the 17th century, from which the decline began. The increase in slavery on the African Atlantic coast, introduced by the Muslims from the north, probably had a lot to do with it, which meant the implantation of an economic niche against which it was impossible to compete because in the south it also experienced a great leap with the establishment of of famous Atlantic triangle Europe-Africa-America. Furthermore, from the eighteenth century, up to eighty percent of the slaves captured by slavers in the Niger Delta would be Igbo.

On the other hand, the spread of Christianity, initiated by the Portuguese when they settled in the area of the Gulf of Guinea and which they sought to promote to facilitate trade, found it easy to take root, given the analogies with the religion of the Igbo. And it is that, as we saw, there was the aforementioned resemblance of the eze with the Pope and a message of fraternal peace among all men that conformed very well to Christian precepts; but there were other points in that sense.

For example, monotheism represented by Chukwu, a single creator god (although there were lesser gods); a fertility goddess (Ala), daughter of the former, represented iconographically as a seated female figure holding a child, just like the Virgin; an envoy from Chukwu to the world to spread his word, preferably to the humble, in the manner of Jesus Christ (Agbala); a sacred city (Nri) whose mere visit absolved of guilt, like Rome; the concept of a divine justice (Ofo and Ogú); the assignment of a spiritual tutor (Chi), such as the Catholic confessor; even the existence of an evil spirit (Odinani) comparable to the devil.

Nri managed to survive thanks to the persecution of slavery carried out by the West Africa Squadron and the export of palm oil. However, it was already greatly weakened in 1911, the year the British Empire ended it by intervening militarily to dispossess the eze from his authority and submit the territory to the colonial administration of the delta protectorate, agreed upon at the Berlin Conference but not made effective until then.

There are those who consider that the ephemeral Republic of Biafra, which tried to become independent from Nigeria in 1966 with a failed and tragic end, was an epilogue of that Igbo kingdom, as this ethnic group was the one that rose up against the domination of the northern states. Added to the ethnic, linguistic and religious complexity was a new element unknown until then that displaced palm oil:oil from the delta and its control.