The fact that the African continent was an unknown place for the most part until the second half of the 19th century does not mean that it did not accumulate numerous explorations to try to unravel its mysteries. And they were not only made in the Contemporary Age because the rosary of them goes back to Antiquity. For example, here we have talked about cases such as the expedition sent by Nero to Ethiopia and the five, also Roman, that crossed the Sahel to the regions of Senegal, Niger and Chad. But even before there were attempts and one of the most famous is the Egyptian-Phoenician voyage that had the mission of circumnavigating Africa.

It is told by Herodotus -and only by him because there are no other documentary sources- in Melpomene , the fourth chapter of his work The nine books of History . He begins in his epigraph 41 outlining the coordinates of that continent, which at that time was known as Libya and which did not properly include Egypt. Says the famous Greek historian:

And it continues in epigraph 42 referring to its enormous extension:

Here we get into the matter. The Necos he mentions was Necho II, pharaoh of the XXVI dynasty, son of Psammetichus I, who ruled Egypt between 610 and 595 BC. Neco's period was characterized by his military victory against the Kingdom of Judah, which he managed to maintain as a vassal state, and by his clashes with the Babylonians, before whom he was first defeated at the Battle of Carchemish but later managed to repel their attempt to invasion, ensuring control of the strategic Syrian-Palestinian strip.

This last meant that Phoenicia was also under his orbit and, since an art of navigation and shipbuilding had been developed there without parallel in the Oecumene (that is, the known world), Neco decided to resort to the Phoenicians to carry out carried out an ambitious plan:to circumnavigate Africa in search of a passage that would allow him to cross from East to West. It was not a simple whim; the pharaoh intended to connect both worlds to improve trade relations.

In fact, it was not the first company that he undertook in this regard. Shortly before, he had commissioned the continuation of the excavation of a channel that would connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea to facilitate maritime transport, following the idea of some predecessors who had left it unfinished. Under Ramses II, for example, a hundred kilometers were built that remained unfinished when calculation errors were discovered. Necho resumed the works linking Lake Timsah with the Bitter Lakes but also stopped when he was warned that this channel could facilitate an outside invasion.

Later, the Persian Darío I and the Roman Trajano would finish the works connecting the canal with Suez, although the caliph Al-Mansur would order it to be closed for the same strategic reasons that were used before the pharaoh. But that is another story. Now we have to go back because Necao did not give up and thought that if that artificial route was not recommended, perhaps there was another natural one far enough away not to fear from the military point of view but, at the same time, close, to be useful from the economic point of view.

Let it be Herodotus who tells it again:

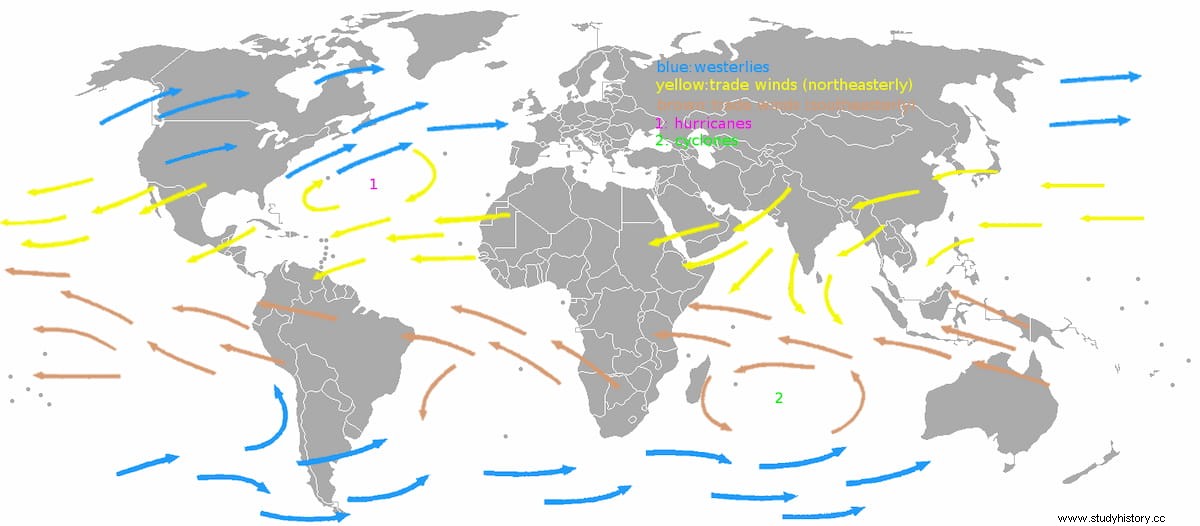

As can be seen, that voyage followed the opposite direction to what the Portuguese would do centuries later:instead of descending through the Atlantic Ocean and rounding the Cape of Good Hope heading east, they had to set sail from Egypt in summer, cross the Red Sea (the Arabian Gulf that Herodotus says) taking advantage of the north wind and leaving behind the Horn of Africa. This entire area was not unknown to the Egyptians (who would be the ones directing the operation even if the crew was Phoenician) because they traded with the country of Punt (probably located in present-day Ethiopia) and Saba (what is now Yemen).

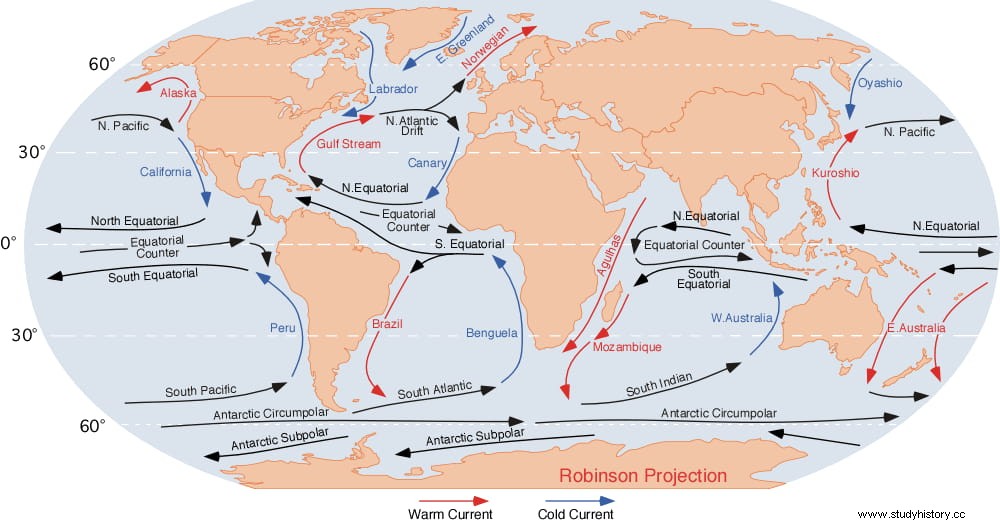

They would sail south parallel to the eastern African coastline, taking advantage of the northeast monsoon (which began to blow in autumn), and as they passed the equator they would enter the Indian Ocean taking advantage of the Needle Current (a warm and strong marine flow that bathes the southeastern African fringe). That current made it easy for them to quickly cross the Mozambique Channel to turn west. This way they would double the cape, heading for the Atlantic and taking the trade winds from the southeast.

Before, the place where they anchored and sowed (probably wheat) must have been the Bay of Saint Helena, in what is now South Africa. They would have been traveling for a year by then, so it would be summer again. In fact, the real reason for stopping was not so much to harvest as to careen the ships. Once they collected, around November, they resumed the march, which would still bring them another two more years until they reached their destination. The Benguela Current, which runs parallel to the coast in a northerly direction, helped them rise through the Atlantic together with the impulse of the aforementioned trade winds.

They may have been surprised to see that the coastline entered the sea to the west, forming the Gulf of Guinea, but it was not an insurmountable obstacle because another current, what we precisely call the Guinea current, helped them coast. But then, in spring, it changes direction and, furthermore, when it returns to the north, the trade winds from the northeast -which do not blow in favor- and another contrary current, that of the Canary Islands, would be found. There, doubts arise about the viability of that adventure, since all this, some experts believe, would prevent them from advancing beyond Cape Bojador (in Western Sahara).

That does not mean that everything ended there because perhaps they continued by land, following the commercial routes that the Phoenicians had opened from their North African colonies (Carthage, Tangier, Mogador, Lixus, etc.) and, upon reaching these, re-embarked towards Egypt. Or, if we insist on believing the story literally, they could resort to oars to possibly reach the Bay of Arguin, in Mauritania, where they made another stop to repair the ships and plant once more.

In that place they may have made contact with the Berbers and learned of the existence of gold in the Bambuque region (between Senegal and Mali), news that probably prompted them to later found the Kerne factory and would be one of the spurs of the Carthaginian expedition. of Hanu. In May they would harvest and go to sea, going up the Moroccan coast and taking advantage of the aforementioned rosary of colonies. As we have seen, Herodotus says that they crossed the Pillars of Hercules, that is, the Strait of Gibraltar, in whose surroundings there were also Phoenician cities such as Gadir (Cádiz) or Malaca (Málaga).

Navigating the Mediterranean to Egypt must have been child's play compared to the previous odyssey. Anyway, be that as it may, by sea or by land, the expedition would have managed to return to the starting point at the end of the summer season, thus completing the return to Africa in three years. Herodotus ends the account of him saying:

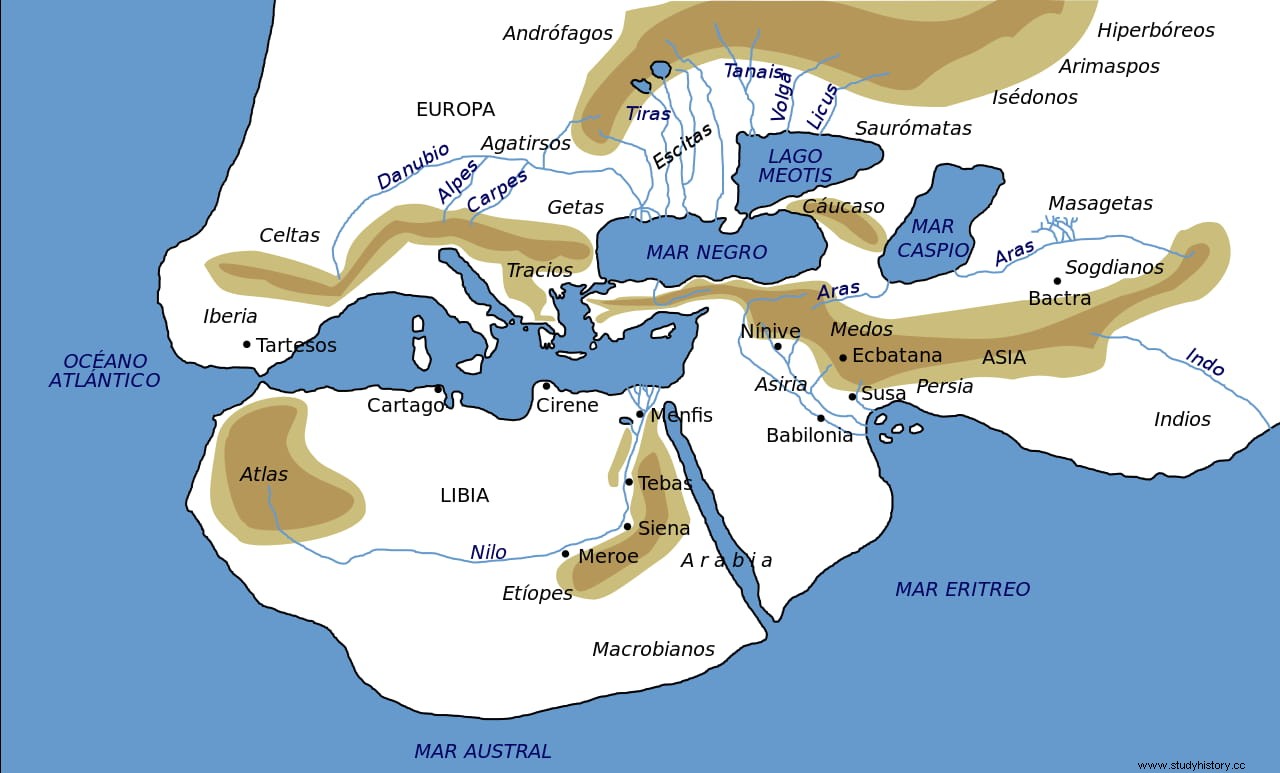

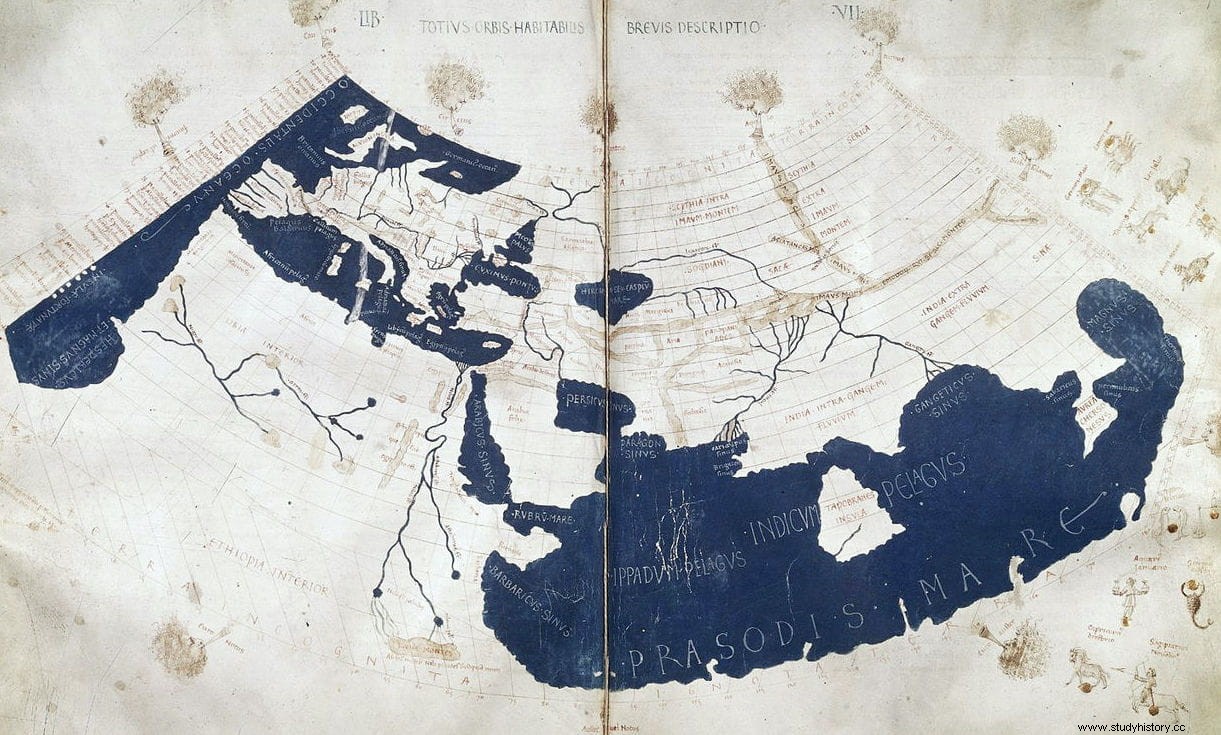

It refers, obviously, to the Atlantic section of navigation, in which they would see the midday sun to the north, a detail that paradoxically gives credibility to this episode despite the fact that the Greek historian was skeptical because he did not know the sphericity of the Earth. But precisely for that. Two centuries were still to go before Eratosthenes was born, who was the first to calculate the earth's circumference and also, at that time, it was thought that the size of Africa was much smaller than it really was (see map 1); It was the Portuguese navigators who demonstrated that the southern end of the continent was below the Tropic of Capricorn, proving Ptolemy right, who affirmed that the dimensions of the continent were enormous.

Of course, at the same time, they took it away; for Ptolemy, circumnavigation was not only impossible because of its size but also because it was not clear that there was a Southern Sea in the southern part of Africa (map 2) and, therefore, like Strabo, Pliny and Polybius, he believed that the story of Herodotus was false... until Bartolomé Díaz showed that the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans were connected and, consequently, it was possible to surround that land, although he did it the other way around.